Does a high level of national debt impose a burden on future generations who must pay it off? In recent years, economists such as Blanchard (2019) and Furman and Summers (2020) have suggested that the answer may be no, because r < g: the real interest rate on debt is usually below the growth rate of the economy. Under that condition, the government can roll over the debt and accumulate interest without raising taxes, and the debt/GDP ratio will fall over time. This idea has decreased concern about the high current level of US debt.

Thinking on this issue has been influenced by a salient historical experience: the decline in the US debt/GDP ratio after WWII. Paying for the war increased this ratio from 42% in fiscal year 1941 to 106% in 1946, but then it started to fall and reached a trough of 23% in fiscal year 1974. As Elmendorf and Mankiw (1999) report, “an important factor behind the dramatic drop between 1945 and 1975 is that the growth rate of GDP exceeded the interest rate on government debt for most of that period.” Krugman (2012) says that the “debt from World War II was never repaid and just became increasingly irrelevant as the US economy grew.” This interpretation of history lends credence to the idea that a high level of debt should not cause great concern.

However, other researchers have suggested reasons to question this interpretation. First, as discussed by authors such as Hall and Sargent (2011) and Eichengreen and Esteves (2022a, 2022b), the US actually paid off part of the WWII debt by running primary surpluses—by levying taxes in excess of current government spending—over much of the period when the debt/GDP ratio was falling. Second, as discussed by authors such as Reinhart and Sbrancia (2015), interest rates were held down relative to economic growth through policies that are not likely to be feasible and/or desirable in the future. These policies included episodes of financial repression, most clearly the Fed’s pegging of interest rates at low levels from 1942 to 1951, which was aimed at decreasing the cost of the war. In addition, ex-post real interest rates were reduced by unexpected rises in inflation in the aftermath of the war and later in the 1960s and 1970s. Because of these factors, the post-war experience does not necessarily suggest that the US economy naturally grows out of debt.

In a recent paper (Acalin and Ball 2023), we seek to quantify the different factors driving the debt/GDP ratio since its 1946 peak. To do so, we construct a term structure of inflation expectations from surveys of short- and long-term expectations, which allows us to estimate the effects of surprise inflation on the real returns on debt. We also estimate the effects of the pre-1952 interest rate peg by comparing the pegged rates on debt of various maturities to market rates during the post-peg period of 1952-1960. Finally, we measure the fractions of outstanding debt in a given year that were issued in each earlier year—the ‘reverse maturity structure’ of the debt—which we do using granular data on Treasury securities produced by Hall et al. (2018) before 1960 and by the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) thereafter. The reverse maturity structure matters because the debt in a given year may include some securities issued during the pre-1952 peg and some issued later, and because inflation expectations differed at the various times securities were issued.

Counterfactual debt paths

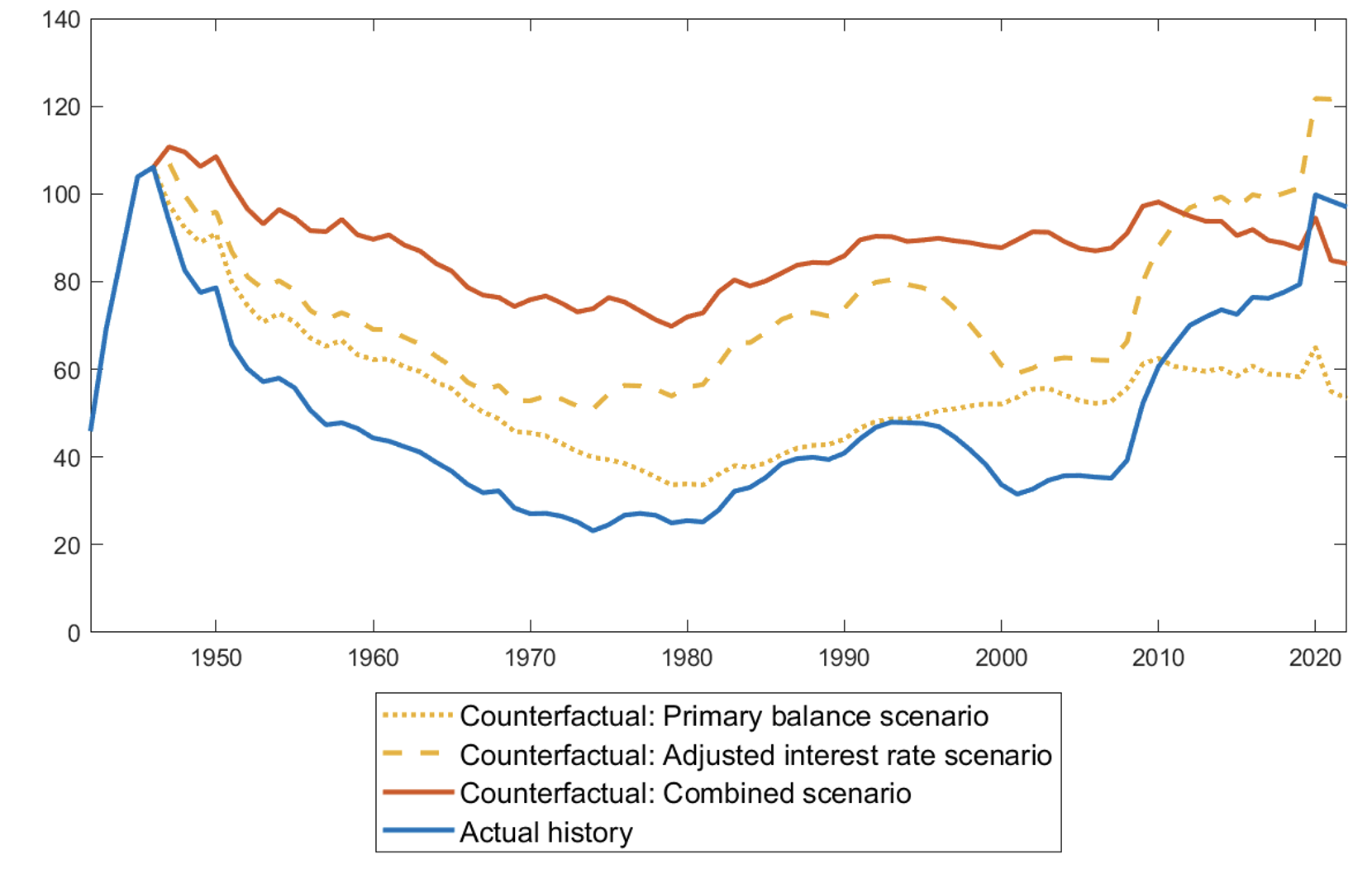

We summarise our findings by presenting the paths of the debt/GDP ratio in three counterfactual scenarios. In one, the ‘primary balance scenario’, we set the primary surplus to zero in all years (but leave interest rates unchanged at their historical levels). In another, the ‘adjusted interest rate scenario’, we eliminate the effects on rates of both surprise inflation and the Fed’s peg before 1952 (but leave primary surpluses at their historical levels). Finally, in a ‘combined scenario’ we assume primary balance and also adjust interest rates. The combined scenario shows how much the debt/GDP ratio was reduced by growth rates in excess of undistorted real interest rates—the decrease that reflects the economy’s natural tendency to grow out of debt.

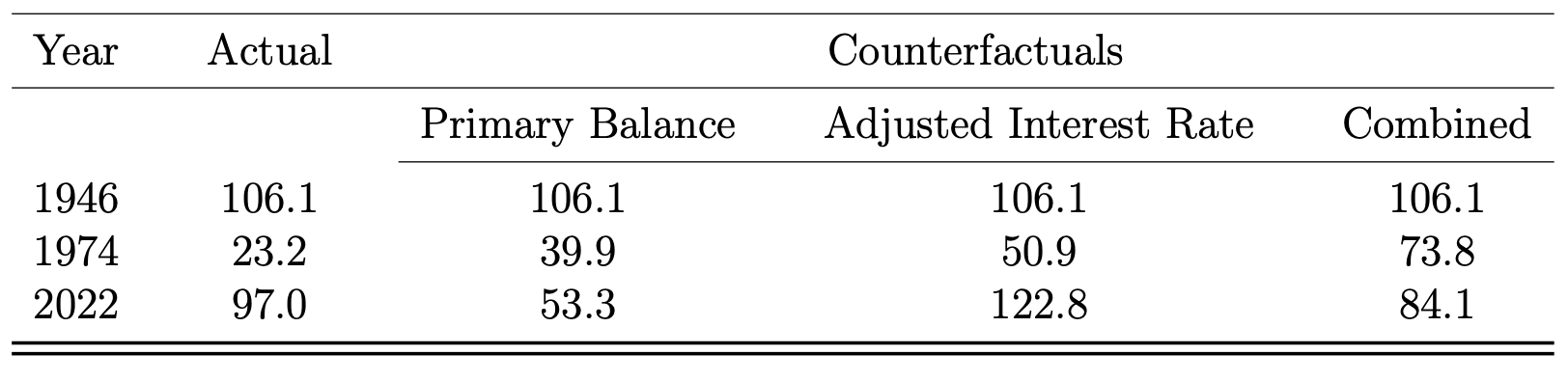

Figure 1 presents the actual and counterfactual paths of debt/GDP, which all start with the ratio at its actual level of 106% in 1946. In interpreting these results, we divide the period since 1946 into two parts: 1946-1974, when the actual debt/GDP ratio declined to its trough of 23%; and 1975-2022, when the ratio rose to 97%. For each counterfactual, Table 1 reports the total changes in debt/GDP over the two periods.

Over 1946-1974, the actual debt/GDP ratio declined steeply. Our counterfactual ratios also decline, but more slowly. As a result, while the actual debt/GDP ratio reached 23% in 1974, the counterfactual ratios in 1974 are substantially higher: 40% in the primary balance scenario, 51% in the adjusted rate scenario, and 74% in the combined scenario. Over the three decades after WWII, the natural erosion of debt from economic growth, as captured by the combined scenario, was considerably smaller than is often suggested.

Figure 1 Debt/GDP paths: Counterfactual scenarios

Note: The lines represent the path of the debt-GDP ratio in actual history and our different counterfactual scenarios. Source: Authors’ calculations

To appreciate these results, recall that the actual debt/GDP ratio fell by 83 percentage points from 1946 to 1974 (from 106% to 23%). In the combined scenario, the ratio falls by only 32 points (from 106% to 74%). Therefore, of the actual 83-point fall, 51 points are explained by the combination of primary surpluses and interest rate distortions. By comparing the different counterfactuals, we can divide these 51 points into 17 points explained by primary surpluses alone, 28 points explained by interest rate distortions alone, and six points from the interaction of the two factors. The interaction arises because adjusting the primary balance raises the level of debt, and higher debt magnifies the effects of adjusting interest rates.

When we extend our counterfactuals to 2022, they yield even more negative findings about growing out of debt. In the combined counterfactual with primary balance and undistorted real interest rates, the debt/GDP ratio falls from its 1974 level of 74% to 70% in 1979, but then starts to rise. The rise in the combined counterfactual ratio reflects the fact that the economy's growth rate has averaged less than the undistorted real interest rate on debt since 1980. In 2022, the counterfactual debt/GDP ratio is 84%: the earlier decline in the ratio is partially reversed. (The actual debt/GDP ratio has risen from its trough of 23% to 97%, mostly because of a shift from primary surpluses before 1974 to large primary deficits in recent decades.)

Table 1 Debt/GDP ratio: Actual and counterfactuals (%)

Notes: The table shows the values of the debt/GDP ratio in actual history and our counterfactuals in 1946, 1974, and 2022.

Source: OMB, authors’ calculations

Looking forward

All in all, our findings cast doubt on the common narrative that the US ‘grew its way’ out of its WWII debt. Over the 76 years from 1946 to 2022, economic growth without primary surpluses or interest-rate distortions would have reduced the debt/GDP ratio by only 22 percentage points, from 106% to 84%. History suggests that we should not count on a major contribution from economic growth to resolving the problem of a high debt level.

What then are the prospects for reducing the debt/GDP ratio from its current level of 97%? It is unlikely that the interest-rate distortions that reduced the ratio after WWII will occur again. Presumably, US policymakers are not considering the kind of interest-rate peg that was imposed during WWII (which required price controls to contain the inflationary effects). And despite the recent surge in inflation, the Federal Reserve appears committed to pushing inflation back down and keeping it low, which would preclude debt erosion through surprise inflation. Additionally, any inflation surprises that occur will have smaller effects than they did in the past because the average maturity of the debt is shorter (Aizenman and Marion 2009, 2011 and Hilscher at al. 2014, 2021).

The upshot is that reducing the debt/GDP ratio will probably require primary budget surpluses. Yet surpluses also appear unlikely: under current policy, the Congressional Budget Office predicts large primary deficits over the next three decades. Absent a major shift toward fiscal consolidation, these deficits are likely to push the debt/GDP ratio to higher and potentially unsustainable levels.

Authors' note: The views herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board or its management

References

Acalin, J and L Ball (2023), “Did the US really grow its way out of its WWII debt?”, NBER Working Paper No. w31577.

Aizenman, J and N Marion (2009), “Using inflation to erode the US public debt”, VoxEU.org, 18 December.

Aizenman, J and N Marion (2011), “Using Inflation to Erode the U.S. Public Debt”, Journal of Macroeconomics 33: 524–541.

Blanchard, O (2019), “Public Debt and Low Interest Rates”, American Economic Review 109: 1197–12.

Eichengreen, B and R Esteves (2022a), “Up and Away? Inflation and Debt Consolidation in Historical Perspective”, Oxford Open Economics 1.

Eichengreen, B and R Esteves (2022b), “Up and away: Inflation and debt consolidation in historical perspective”, VoxEU.org, 15 November.

Elmendorf, D W and N G Mankiw (1999), “Government Debt”, Handbook of Macroeconomics 1: 1615–1669.

Furman, J and L Summers (2020), “A Reconsideration of Fiscal Policy in the Era of Low Interest Rates”, unpublished manuscript, Brookings Institution.

Hall, G, J Payne and T J Sargent (2018), “US Federal Debt 1776-1960: Quantities and Prices”, Working Paper 18-25, New York University, Leonard N. Stern School of Business, Department of Economics.

Hall, G J and T J Sargent (2011), “Interest Rate Risk and Other Determinants of Post-WWII US Government Debt/GDP Dynamics”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 3: 192–214.

Hilscher, J, A Raviv, and R Reis (2014), “Will the US inflate away its public debt?”, VoxEU.org, 7 August.

Hilscher, J, A Raviv and R Reis (2021), “Inflating Away the Public Debt? An Empirical Assessment”, The Review of Financial Studies 35(3): 1553-1595.

Krugman, P (2012), “Nobody Understands Debt”, The New York Times, 1 January.

Reinhart, C M and M B Sbrancia (2015), “The Liquidation of Government Debt”, Economic Policy 30: 291–333.