Over the past 50 years, central banks around the world have progressively increased their degree of independence, which is often considered the backbone of modern economic policy analysis (Masciandaro and Romelli 2023).

However, following the COVID-19 pandemic, the rise in consumer price inflation and the monetary policy tightening experienced by many economies have contributed to the re-emergence of central bank independence as a major concern among politicians. For instance, on multiple occasions, former US President Donald Trump openly criticised the Federal Reserve’s conduct of monetary policy via Twitter (Bianchi et al., 2020).

To contribute to a better understanding of the evolution of central bank institutional design in recent years, in a new paper (Romelli, 2024) I update the Central Bank Independence – Extended (CBIE) index in Romelli (2022) to document trends in central bank independence for 155 countries during the period 1923-2023, thus extending the sample period of the CBIE index by six years so that it now ends in 2023. The period of coverage of the CBIE index is also extended from a historical perspective, as the data I present start in the year of the first available legislation (1923 for Colombia, 1933 for New Zealand, 1934 for India, etc.). The data on the CBIE index as well as those on the classical indices of central bank independence – Grilli et al. (1991) (henceforth, GMT) and Cukierman et al. (1992) (henceforth, CWN) – are freely available at https://dromelli.github.io/cbidata/index.html, together with the full set of central bank legislations analysed.

Reforms and trends in central bank independence

To identify the number of reforms and trends in central bank independence, I first collect all the central bank charters and their amendments over the period 1923-2023. More than 2,000 changes to central bank legislation took place throughout this period. Yet, these legislative changes may not necessarily have modified, in a significant way, the institutional design of central banks. To gauge the magnitude and significance of these legislative changes, I focus my attention on reforms that changed the degree of central bank independence.

For each year in which a change to the central bank charter occurred, I recompute the value of the CBIE index. A reform is then defined as a date on which the level of the CBIE index changes. This also allows the construction of an index of central bank independence that changes over time. This historical exploration allows the identification of a total of 370 reforms in central bank design, of which 279 are classified as improvements to central bank independence and 91 as reversals of independence.

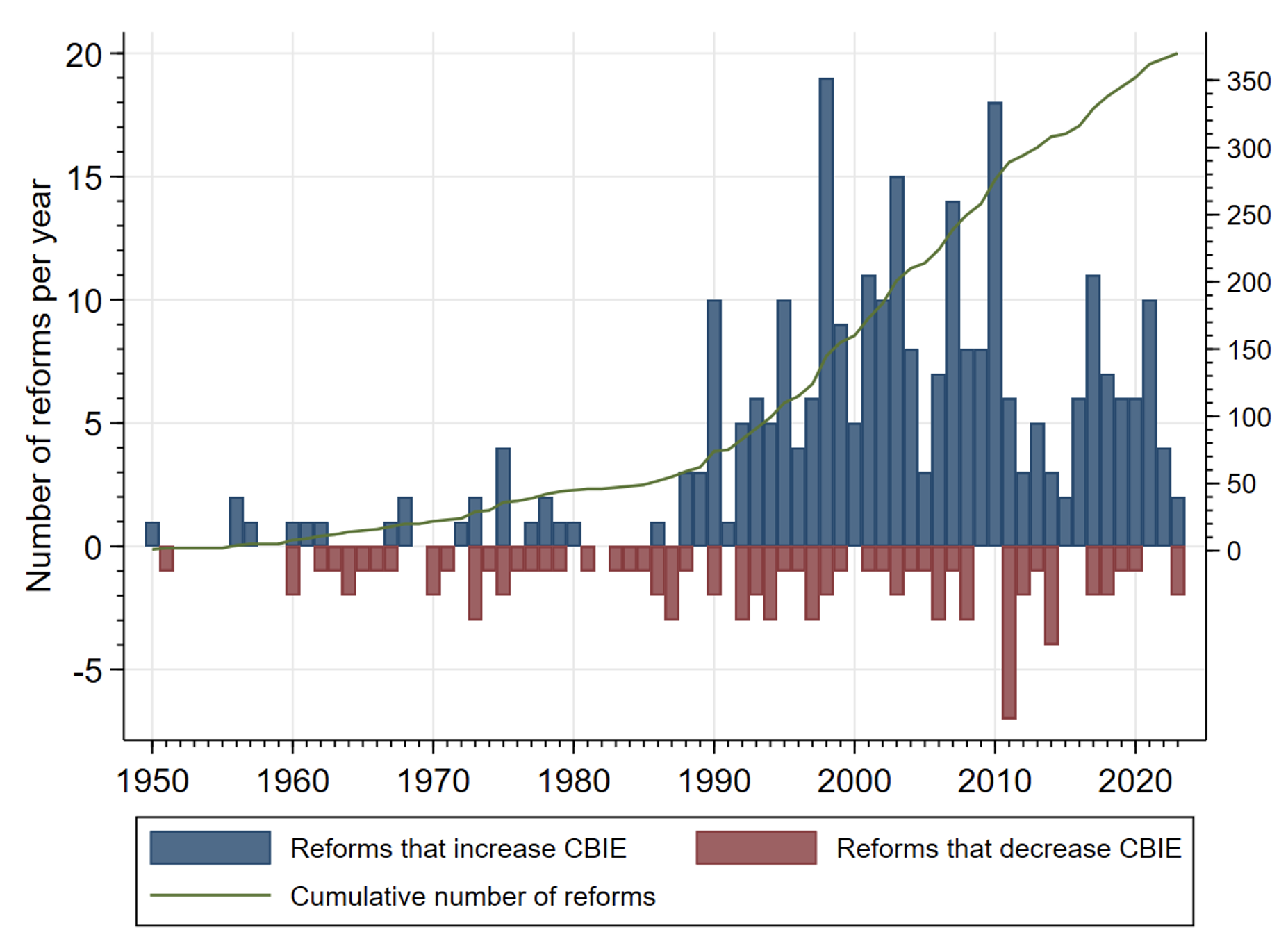

Figure 1 Central bank legislative reforms, 1950-2023

Note: The figure shows the frequency of reforms that increased/decreased the CBIE index, together with the cumulative number of reforms in central bank independence between 1950 and 2023.

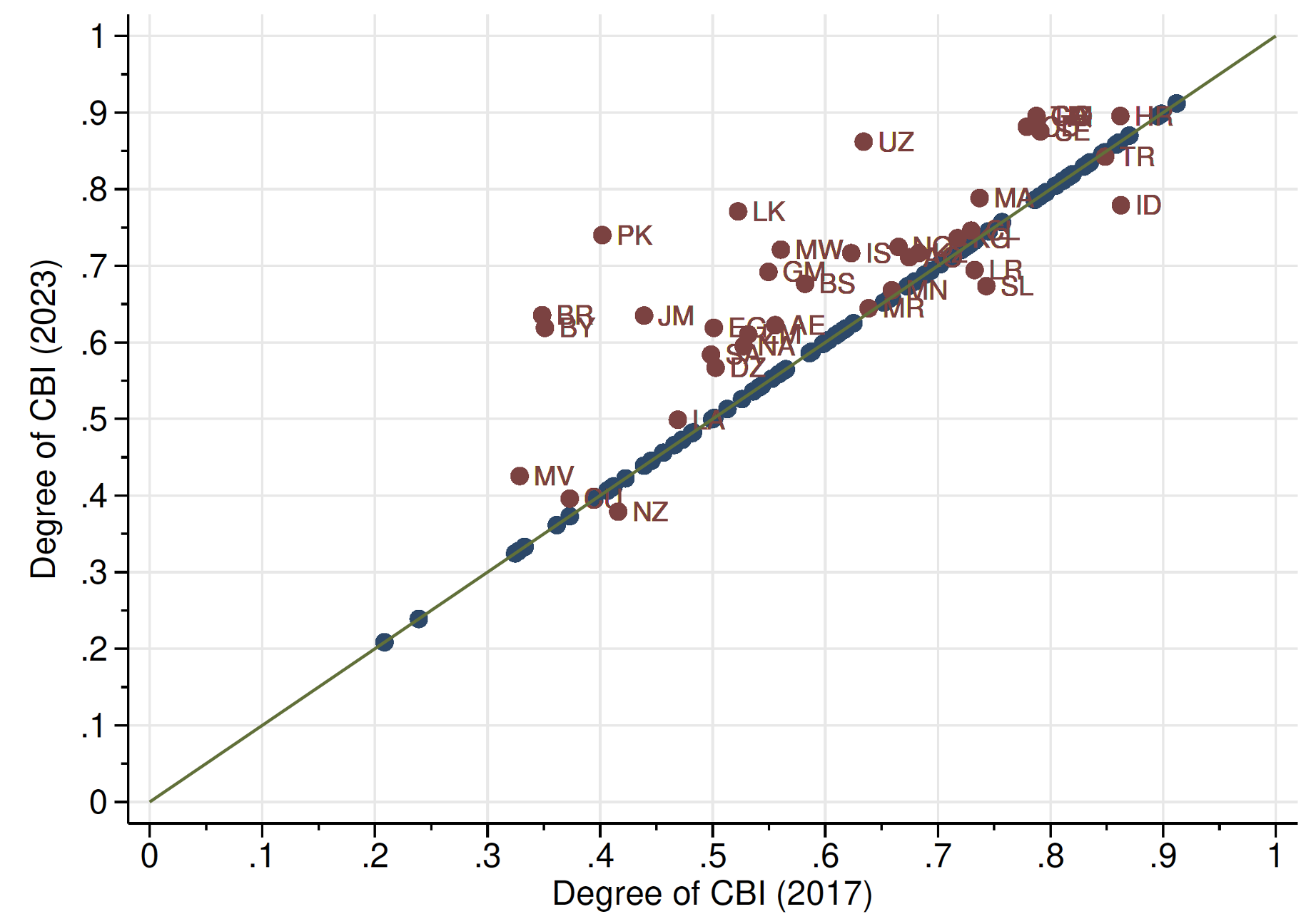

Figure 1 shows the distribution of reforms over time. A large number of reforms occurred during the 1990s, with a peak in 1998 when the ECB became the sole monetary policy authority for the euro area countries. A wave of reforms can also be seen following the 2008 financial crisis, with increases mainly associated with improvements in the degree of independence along the dimension related to the governor and board, and reverses corresponding to reforms regarding the involvement of central banks in banking supervision. Finally, a last wave of reforms mainly focused on improving the degree of central bank independence can be seen starting from 2016. This is confirmed in Figure 2, which compares the degree of central bank independence proxied by the CBIE index in 2017 and 2023, i.e. since the last available year of the CBIE data in Romelli (2022) and the current update of the index. As most of the countries lying outside the 45-degree line are clustered above it, this provides evidence of a renewed tendency towards improving the degree of central bank independence.

Figure 2 Reforms to central bank independence, 2017 versus 2023

Note: The figure compares the level of central bank independence proxied by the CBIE index in 2017 and 2023.

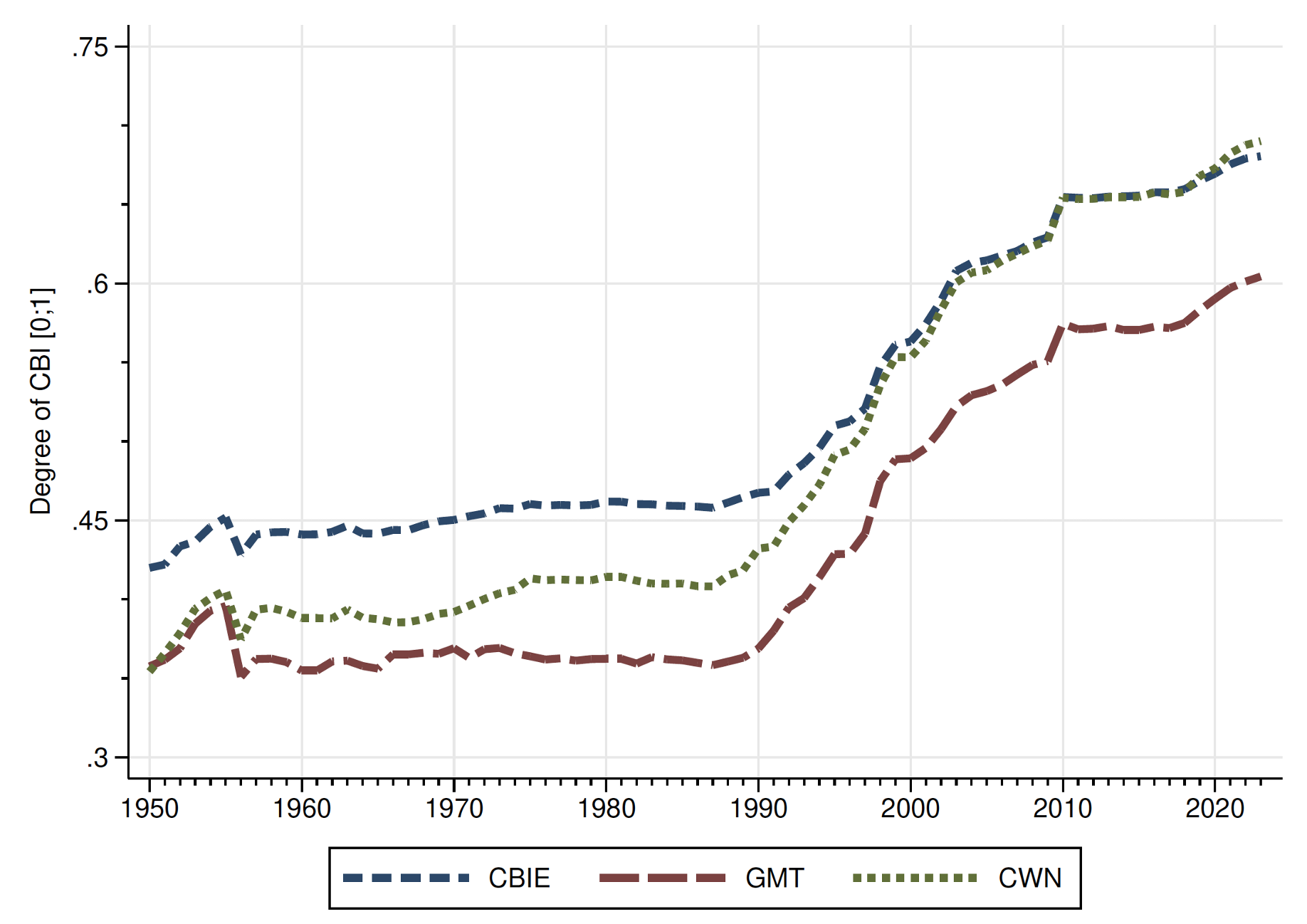

Figure 3 shows the level and trends in the indices of central bank independence presented in my paper. As suggested by the trend of reforms presented in Figure 1, the level of central bank independence across the CBIE, GMT and CWN indices of central bank independence remained stable until the late 1980s. After that, the average level of independence increased at a constant pace until 2010. From the post-global financial crisis period up until 2015, the average level of independence remained almost unchanged, but a new wave of reforms seems to have started since 2016.

Figure 3 Evolution of central bank independence, 1950-2023

Note: The figure shows the evolution of the CBIE, GMT and CWN indices of central bank independence between 1950 and 2023.

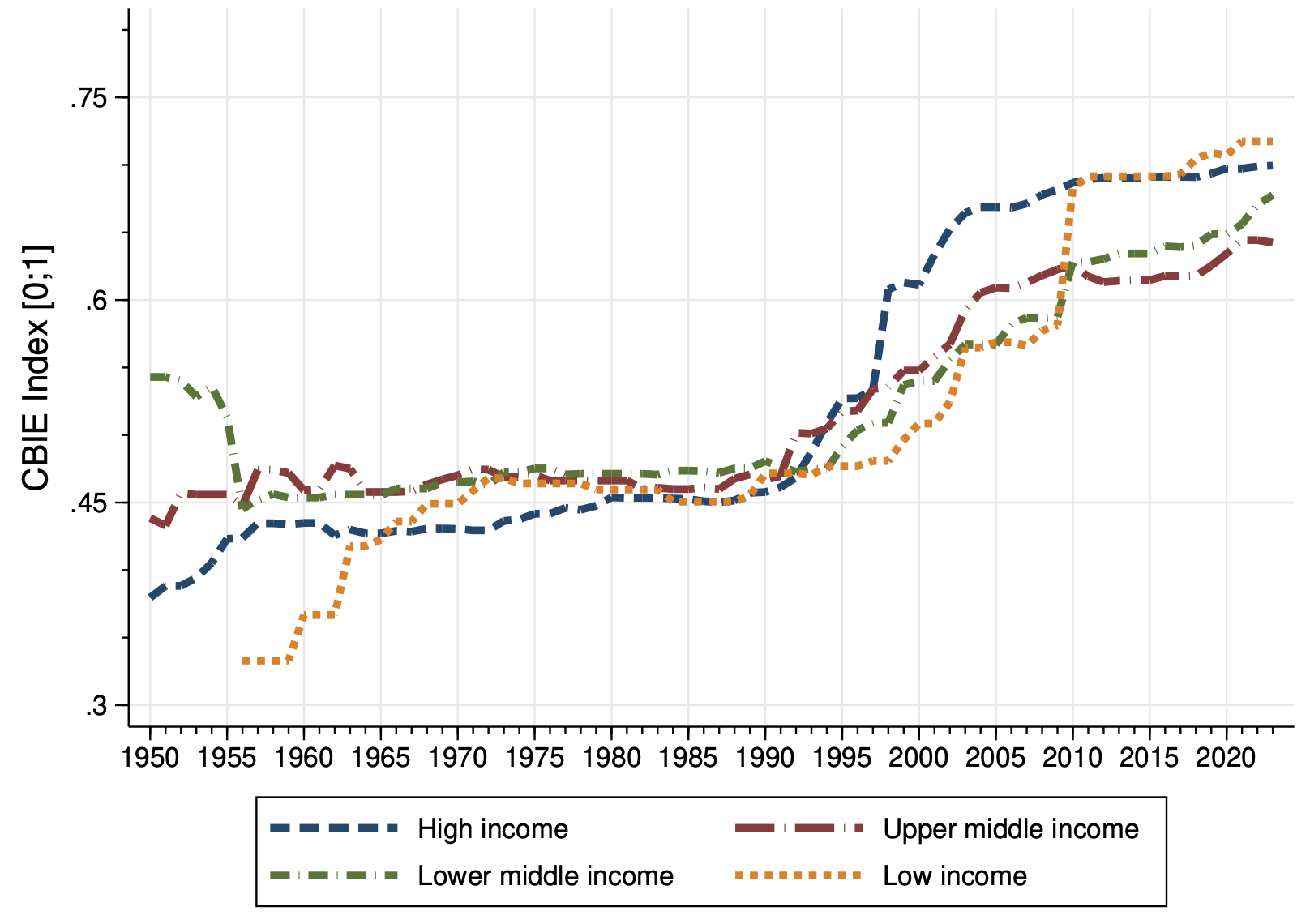

Figure 4 shows the evolution of the CBIE index from 1950 until 2023 by clusters of economic development (i.e. high-income, upper-middle-income, lower-middle-income, and low-income countries), based on the 2022 World Bank classification. Surprisingly, the average level of central bank independence in low-income countries is similar to that of high-income countries, following the sharp increase experienced by the former countries in 2010 as a result of a large reform which brought a change in the degree of independence of the Central Bank of West African States from 0.36 to 0.81. Excluding the sample of low-income countries, it appears that central bank independence tends to be increasing in the level of economic development and has been trending upward for all four groups since the early 1990s.

Figure 4 Evolution of central bank independence by level of economic development

Note: The figure shows the evolution of the average degree of independence across central banks grouped based on the 2022 World Bank income classification.

Conclusion

In this column I provide an overview of the evolution of central bank independence for a large sample of 155 countries from 1923 to 2023. Over this period, I identify a total of 370 reforms to central bank design, which highlight a remarkable global shift towards enhancing the independence of monetary authorities. This shift is particularly notable in the context of recent global challenges that emerged following the 2008 global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent resurgence of inflation experienced by many high-income countries since mid-2021, which have revived the debate on the role and scope of central banks. The findings in my paper contribute to these ongoing discussions, offering a nuanced understanding of how central bank independence has been shaped and reshaped over a century. The increase in the degree of central bank independence, observed across countries with varying levels of economic development, signals a broader recognition of the importance of independent monetary policy in maintaining economic stability.

The lessons drawn from this historical analysis underscore the importance of central bank independence not just as an academic concept, but as a crucial component in the formulation of sound economic policies. The amendments to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act between 2018 and 2023 are only one of the many examples of the evolving mandate of central banks. Similarly, the recent inclusion of “environmental sustainability” as an objective in Hungary’s central bank legislation in 2023 highlights the increasing pressure on central banks to align with governmental environmental policies and contribute to the global efforts to achieve net zero emissions. These evolving mandates require central banks to navigate new territories of policymaking while maintaining their core objective of price stability.

The evolving role of central banks is also highlighted by the recent focus on gender diversity, with only a few central banks explicitly mentioning diversity among their objectives. For example, since 2017 the legislation of the National Bank of Rwanda requires that at least 30% of its central bank board members are female. Similarly, the diversity of the board of directors was also introduced in 2023 in the statute of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

The comprehensive dataset on central bank independence detailed in my paper could be used for future research aimed at investigating the effects of central bank independence on macroeconomic variables or the link between de jure and de facto indices of independence. Studies similar to those proposed by Kammer et al. (2023) on inflation and Ioannidou et al. (2023) on political influence in governor appointments could benefit from this freely available dataset to further scrutinise the link between de jure independence and real-world policy outcomes. In particular, such research could elucidate whether increased legal autonomy translates into tangible anti-inflationary success and whether it can effectively withstand the pressures of political appointments, while also accommodating emerging mandates such as environmental sustainability and gender diversity.

References

Cukierman, A, S B Webb and B Neyapti (1992), “Measuring the Independence of Central Banks and its Effects on Policy Outcomes”, World Bank Economic Review 6: 353–98.

Grilli, V, D Masciandaro and G Tabellini (1991), “Political and Monetary Institutions and Public Financial Policies in the Industrial Countries”, Economic Policy 13: 341-92.

Ioannidou V, S Kokas, T Lambert and A Michaelides (2023), “Governor appointments and central bank independence”, VoxEU.org, 4 February.

Kammer A, A Ari, C Mulas-Granados, V Mylonas, L Ratnovski, L and W Zhao (2023), “Beware of premature celebrations on inflation”, VoxEU.org, 3 October.

Kind, T, H Kung and F Bianchi (2020), “Threatening central bank independence one tweet at a time”, VoxEU.org, 25 January.

Masciandaro, D and D Romelli (2023), “Alex Cukierman, a pioneer of central bank independence”, VoxEU.org, 4 November.

Romelli, D (2022), “The political economy of reforms in central bank design: Evidence from a new dataset”, Economic Policy 37(112): 641-88.

Romelli, D (2024), “Trends in central bank independence: a de-jure perspective”, BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 217.