Inflation is back. In advanced economies, 2022 price growth was the highest since the 1980s; in emerging and developing market economies, since the 1990s. For many, especially the most vulnerable, inflation has impacted their ability to provide for themselves and their families. Fighting inflation is thus a key policy priority.

To rein in inflation, major central banks implemented over the past year the most rapid and synchronised cycle of monetary policy tightening in recent history. By now, in the euro area and the UK, policy interest rates are approaching their estimated ‘terminal’ (peak-of-the-cycle) levels. Helped by resolute policy action, euro area and UK headline inflation rates have halved from about 11% late last year to 4.3% and 6.7%, respectively, now. Yet, inflation remains uncomfortably above its 2% target.

Furthermore, the outlook is uncertain. As Jerome Powell said recently, monetary policy is “navigating by the stars under cloudy skies” (Powell 2023). Policymakers face acute trade-offs in their upcoming decisions as they balance the conflicting forces of stubbornly high core inflation, emerging macroeconomic weakness, and uncertain strength and lags of monetary policy transmission. There is also a growing realisation that, in a world dealing with persistent inflation, interest rates may need to stay high for longer.

Lessons from history

This is the first major inflation shock for many. We therefore undertook to study the historical experience of fighting inflation, collecting data from 100 inflation shocks across the world since the 1970s (Ari et al. 2023). Of these, over 50 relate to the 1970s oil crises, which – being externally triggered by surges in essential input prices – bear similarities to energy and food price disruptions caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine, a key driver of inflationary forces in Europe.

These historical experiences tend to amplify the cautioning voices in the current policy debate. The analysis in our paper finds that inflation is most often persistent, that it is critical not to loosen policies prematurely in response to temporary declines in inflation – meaning interest rates will likely need to remain high for longer – and that while fighting inflation often involves short-term pain, this is likely small in relation to the costs of persistently high inflation.

We will now discuss the key findings of our paper in turn.

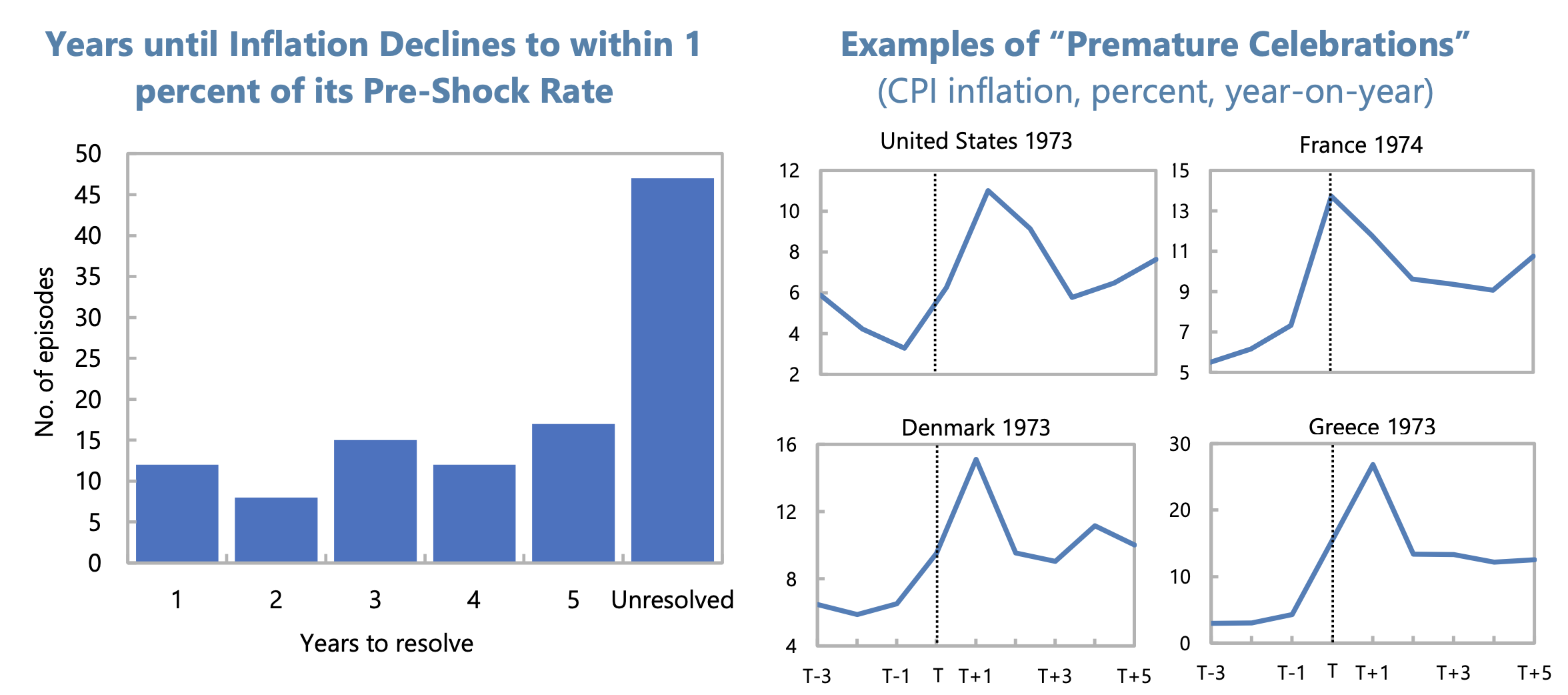

First, inflation is often persistent. It can take years to ‘resolve’ – to bring price growth to pre-shock levels. Historically, 40% of inflation shocks remained unresolved even after five years. In the remaining 60%, it still took an average of three years to return inflation to pre-shock levels.

Second, in fighting inflation, ‘premature celebrations’ – transitory declines in inflation that tempted policymakers to loosen policy too early – are extremely common. In almost all (90%) of the unresolved inflation episodes, inflation declined substantially in the first year or two after the initial shock, only to accelerate again or become sticky at a high level. Premature celebrations appear to be a large risk for policymaking today. Central bankers are right to warn that the fight is far from over, even as recent inflation readings show some welcome moderation.

Figure 1 Years to resolve inflation and some examples of ‘premature celebrations’

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Turning from inflation patterns to inflation-fighting policies

How does the macroeconomic policy stance compare between countries that have successfully resolved inflation in the past and those that have not?

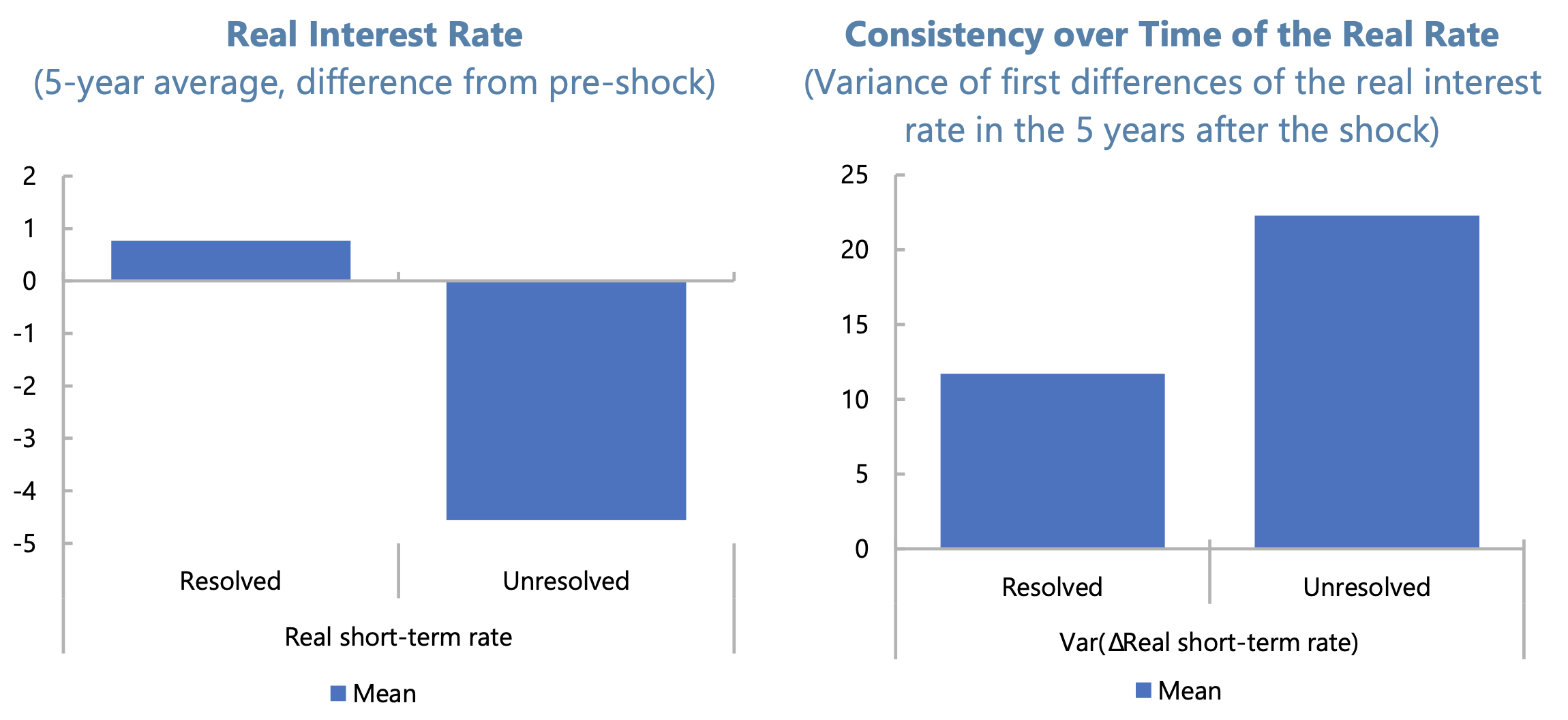

Here the main message from historical experience is that countries that successfully resolved inflation tightened their macroeconomic policies more compared to countries that did not resolve inflation. Moreover, crucially, countries that resolved inflation maintained a consistently tight policy stance over a period of time. These lessons relate primarily to monetary policy, which is at the forefront of the fight against inflation, but they are also important for fiscal policy, which should not add to price pressures and should be clearly targeted to the vulnerable.

Figure 2 Differences in monetary policy stance (post- versus pre-shock), and in its consistency over time, compared between countries that resolved and those did not resolve inflation

Source: IMF staff calculations.

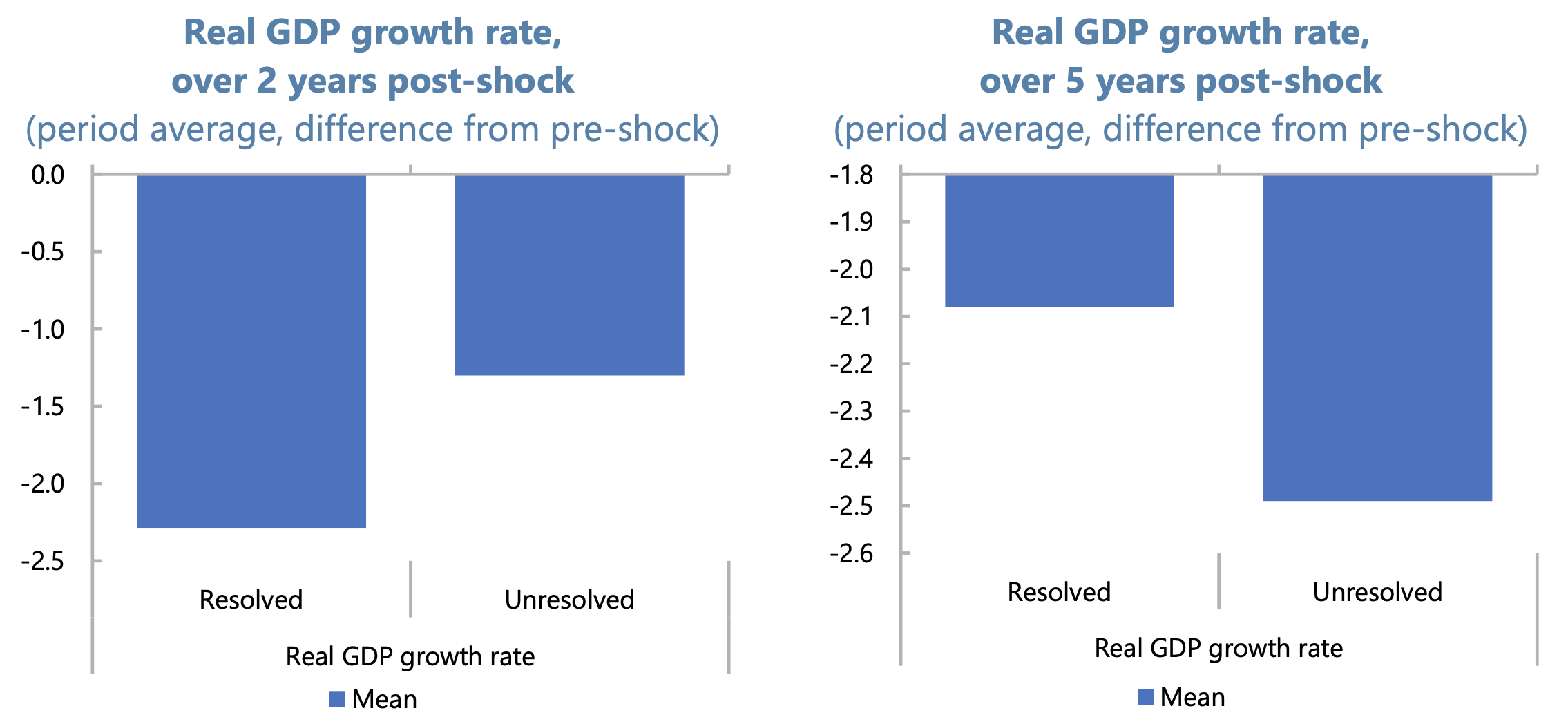

The final lesson is that fighting inflation is difficult in the short-term but pays off in the medium term. In the two years after the inflation shock, counties that resolved inflation experienced lower growth compared to those that did not. This relationship, however, reverted over a longer, five-year horizon where countries that resolved inflation managed to achieve higher growth and lower unemployment compared to countries that ‘let inflation go’.

Figure 3 Growth outcomes in countries that resolved and did not resolve inflation

Source: IMF staff calculations.

The economics behind this finding are intuitive. There is a macroeconomic trade-off between bringing inflation down on the one hand and achieving higher growth and lower unemployment on the other hand. But importantly, these effects are temporary: they dissipate once inflation is successfully brought under control. By contrast, leaving inflation unresolved comes with its own costs of macroeconomic instability and inefficiency. These costs are long-lasting and accumulate for as long as inflation remains high. The implication is that, from a medium- to long-term perspective, cumulative welfare losses are bound to be larger with unresolved or permanently high inflation.

Where does this leave policymakers? The lessons from history seem clear. In the fight against inflation, policymakers should show perseverance, avoid premature celebrations, demonstrate policy credibility and consistency, and keep an eye on the medium-term.

References

Ari, A, C Mulas-Granados, V Mylonas, L Ratnovski and W Zhao (2023), “One Hundred Inflation Shocks: Seven Stylized Facts”, IMF Working Paper WP/2023/190.

Powell, J H (2023), “Inflation: Progress and the Path Ahead”, speech at the Jackson Hole Symposium, 25 August.