As stressed in the pioneering work of Demsetz (1967), the protection and transfer of property varies greatly in efficiency across jurisdictions. In much of the world, property sales are highly regulated and expensive. In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, the process of moving public services online has sped up greatly (Baldwin and Forslid 2020, Kotz et al. 2021), providing an opportunity to reduce compliance costs: holding the level of regulation constant and easing the way in which this regulation is administered.

Social scientists have long devised ways to gauge the compliance costs of regulation. A trailblazer in this field is Hernando de Soto’s (1989) time-and-motion study of starting a business in Lima, Peru. De Soto found that given the enormous burden of administrative procedures, most Peruvian entrepreneurs rationally decided to stay informal, outside the reach of the law. Since de Soto’s influential study, a large literature has developed to test the link between regulatory burden and economic and social outcomes (for early field studies, see for example Field 2005, 2007).

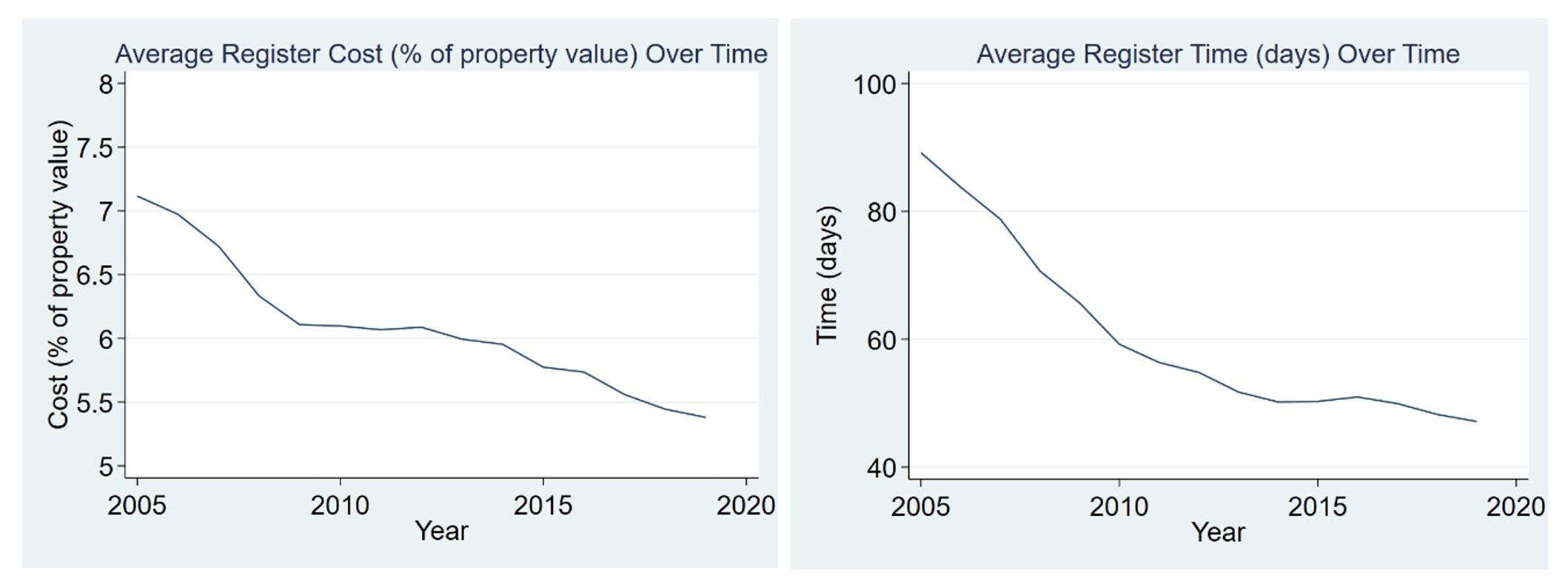

New technology makes it possible to deliver public services online instantaneously and at a fraction of the cost. In a recent study (Djankov et al forthcoming), we show that countries have seen tremendous progress in reducing compliance costs in the area of registering property over the past 15 years. In particular, the average cost of such registration has fallen from 7.1% of property value to 5.4%, while the average time associated with the regulated procedures has fallen from 89 to 47 days, a 47% reduction (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Average cost and time to register property

Source: Djankov et al. (forthcoming).

The improvement in speed of registering commercial property is seen across all income groups, while the reduction in costs comes primarily from the poorest two quintiles of countries catching up with the rest of the world in simplifying registration.

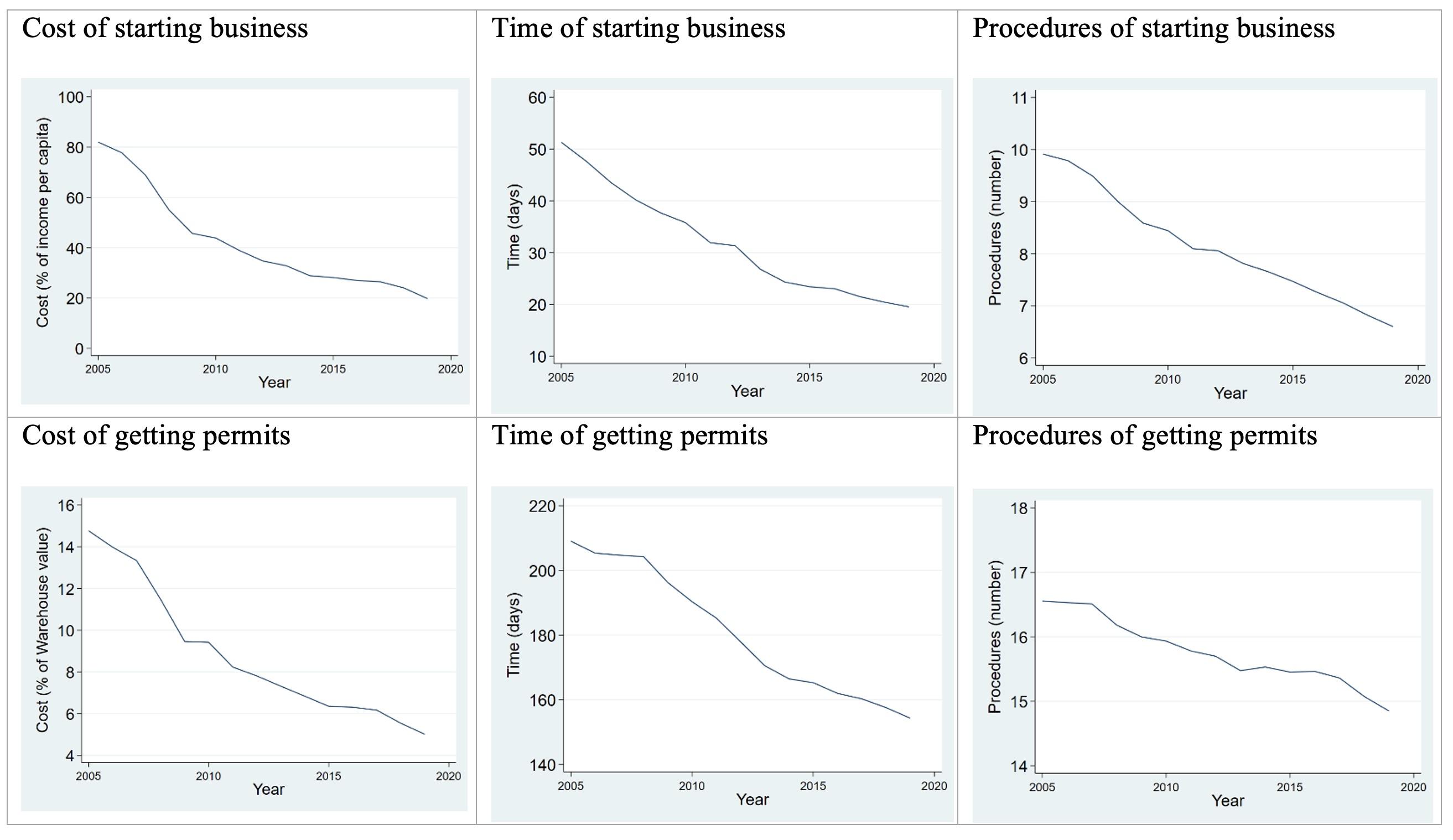

This reduction in compliance costs is seen across other areas of business regulation too, for example in starting a business and dealing with construction permits (Figure 2). In these instances, compliance costs – in terms of time and money - have also fallen significantly over the past 15 years, while the number of procedures has changed less.

Figure 2 Compliance cost and time has fallen, but number of procedures only dropped slightly.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank data.

The number of procedures can also be reduced with the use of online technology, though this process often requires regulatory change. Four countries – Georgia, Norway, Portugal, and Sweden – would make Hernando de Soto proud by having a single-step online property registration (Djankov et al forthcoming). In Norway, for example, there is no need for a lawyer or notary to be involved in the registration process. The application is an online form at the Norwegian Mapping Authority’s website. The fee to receive the title is around $70, and the stamp duty tax is 2.5% of the property value. The registration fee and stamp duty are invoiced to the seller after the registration is completed and are paid online.

Effects of lower compliance costs

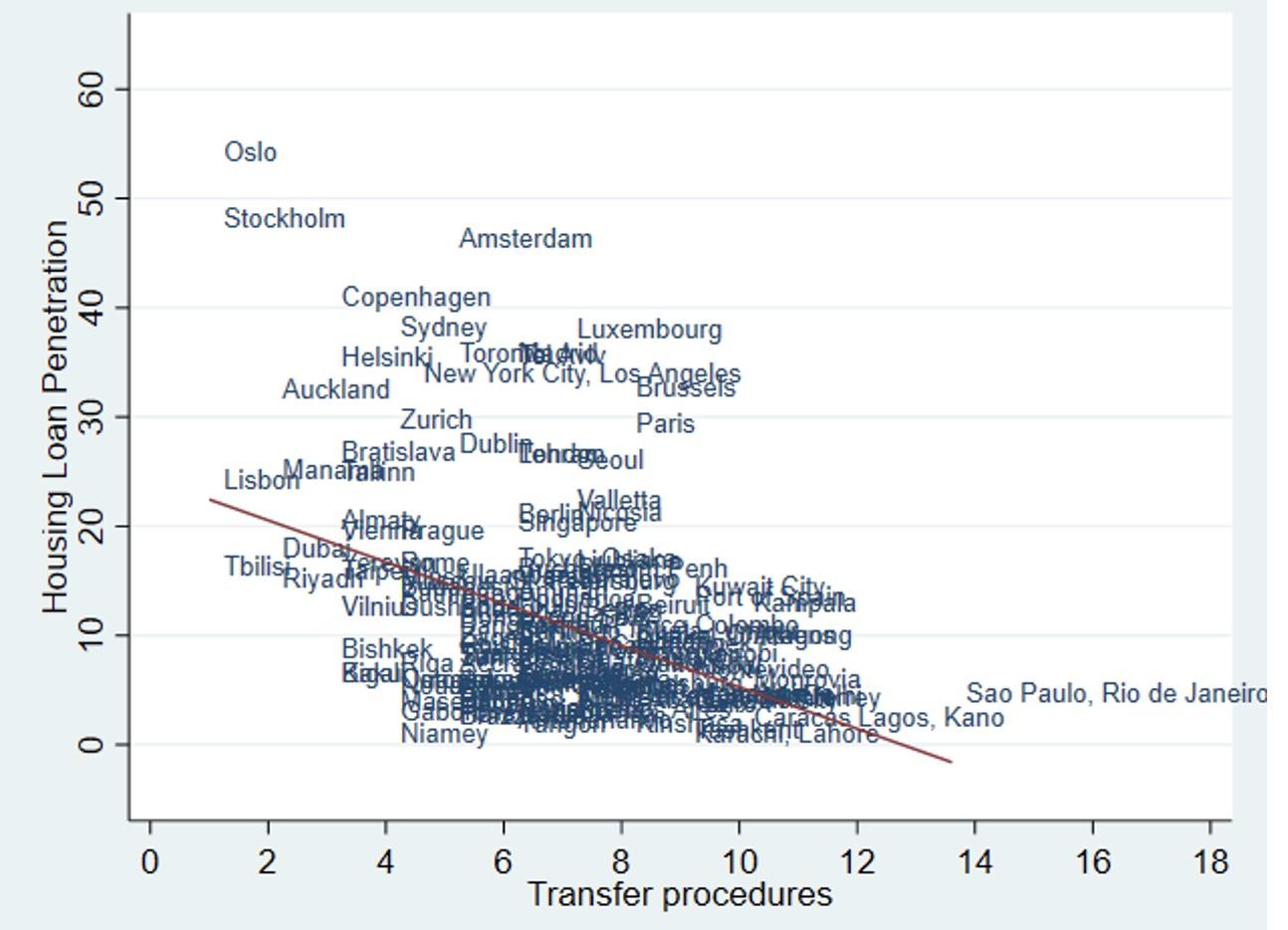

Lower compliance costs are shown to improve the real estate market in countries where adopting online technology has made it easier to buy and sell property. Figure 3 presents the relationship between property registration procedures and housing loan penetration in 138 countries with available data for 2017. The percentage of the adult population with an outstanding loan to purchase a home, obtained from the World Bank’s Global Findex database, is used as a proxy for housing loan penetration. The number of procedures associated with property registration is used as the measure of compliance costs.

Figure 3 Housing loan penetration and property transfer procedures

Note: The red line is the linear fitted line.

Source: Djankov et al. (forthcoming).

While regulators and administrators still pose barriers to transferring property, the good news is that the associated compliance costs are being reduced in many countries, and particularly in the developing world. In line with Demsetz (1967), protection of property rights is costly, but over time the world appears to be moving toward more efficient outcomes. As Demsetz (1967) predicted, as technology lowers the cost of improving property rights, those rights eventually improve too.

References

Baldwin, R and R Forslid (2020), “Covid 19, globotics, and development”, VoxEU.org, 16 July.

De Soto, H (1989), The other path: The invisible revolution in the third world, New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Demsetz, H (1967), “Towards a theory of property rights”, American Economic Review 57: 347-59.

Djankov, S, E Glaeser, A Shleifer, and V Perotti (forthcoming), “Property rights and urban form”, Journal of Law and Economics.

Field, E (2005), “Property rights and investment in urban slums”, Journal of the European Economic Association 3(2-3): 279–290.

Field, E (2007), “Entitled to work: Urban tenure security and the labor supply in Peru”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(4): 1561–1602.

Kotz, H, J Mischke, and S Smit (2021), “Pathways for productivity and growth after the COVID-19 crisis”, VoxEU.org, 3 May.