Teachers are a school’s most important asset. Learning from a highly effective teacher improves not only a student’s test scores in a given year but also important outcomes later in life (Chetty et al. 2014). And yet, collective bargaining agreements and state laws often prohibit traditional public schools from administrative actions that could improve the quality of their teachers, such as removing and replacing low-performing teachers (Goldhaber and Hansen 2010, Staiger and Rockoff 2010, Cowen and Winters 2013) or hiring talented teachers who have not yet obtained a licence (Backes and Hansen 2015, Clarke et al. 2013, Kane et al. 2008).

In contrast, flexibility in teacher employment practices is among the defining features of charter schools – publicly funded but independently operated schools of choice.

In a new study (Bruhn et al. 2020), we find three key facts about teacher quality and mobility that help to better explain teacher labour markets within the context of Massachusetts’s expansive and effective charter-school sector. We find little support for the idea that targeted teacher retention is a primary driver of charter school effectiveness. However, the results do suggest that flexible labour regulations in charter schools create a fertile training ground for teachers, potentially increasing the overall quality of the labour force in traditional public schools.

Compared to teachers in traditional public schools, charter-school teachers work longer hours with more expansive responsibilities for lower salaries and fewer job protections. It’s unsurprising, then, that charter schools retain fewer teachers compared to traditional public schools. For instance, in 2020, traditional public schools in Massachusetts retained about 89% of their teachers, compared to only 71% of teachers in charter schools.1

But not all attrition is bad. In theory, charter schools could take advantage of their regulatory freedom by removing ineffective teachers and by finding and then retaining high-quality teachers who might otherwise slip through the cracks.

Figure 1 illustrates the first key insight revealed by the data: not only is teacher attrition from charter schools higher than in traditional public schools overall, but charter schools disproportionately lose both their highest- and lowest-performing teachers.

The figure bins teachers according to their effectiveness, as measured via their independent contribution (i.e. value-added) to student test score growth. The vertical axis illustrates the probability that a teacher is no longer employed in their school the following year. The relationship between teacher quality and attrition in charter schools is U-shaped, indicating that charter schools disproportionately lose ineffective and highly effective teachers. There is little relationship between teacher quality and attrition within traditional public schools.

Figure 1 Teacher attrition by teacher quality, charter schools vs traditional public schools

The relationship between teacher quality and attrition is similar within both effective and ineffective charter schools. This implies that the pattern documented in Figure 1 is characteristic of charter schooling in general rather than a predictor of effectiveness within the charter sector.

Our second key empirical finding speaks to what happens to teachers after they leave a charter school. Ineffective teachers who leave charter schools tend to stop teaching within the state entirely. But teachers who were effective within charter schools often leave to teach within a traditional public school. There is little relationship between a teacher’s effectiveness and the likelihood of moving into another school among those who leave a traditional public school.

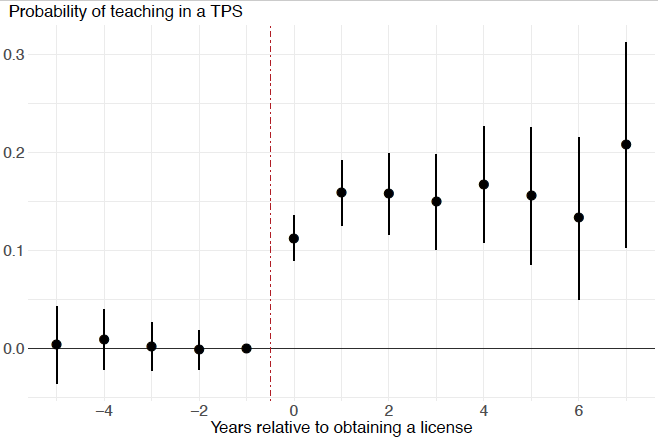

Finally, we show that charter-school teachers are more likely to be unlicensed when they are hired, but, as Figure 2 illustrates, upon obtaining a licence, they become very likely to move into a traditional public school. About 2% of teachers in the average Massachusetts traditional public-school district are unlicensed, compared to about a third of teachers in the average charter school in the state. In 2018, about 40% of teachers placed nationally by the Teach for America – an organisation that recruits recent college graduates from outside education to try teaching for at least three years – taught in a charter school.

Figure 2 Probability of teaching in a traditional public school before vs after obtaining license

Taken together, these three key facts suggest that charter schools act as a filtering mechanism for teacher quality by inducing their worst teachers to leave the education sector while also providing a pathway for their best teachers to enter the traditional public-school system.

Intuitively, we can think of charter schools applying a form of regulatory arbitrage. While traditional public schools impose an entry barrier (licensure) and pay a relatively high wage, charter schools are not subject to these requirements and hence are free to hire unlicensed teachers at a lower wage. This is similar to the way that firms like Uber and Lyft take advantage of loopholes in taxi regulations to enter the personal-transport market and pay lower wages, undercutting the highly regulated incumbent firms.

The main difference between the market for taxis and the market for students is that charter schools are often in restricted supply. For example, Massachusetts has a strict cap on the number of charter schools. Thus, unlicensed prospective teachers can use the charter-school system to explore their taste for teaching. Those who are not successful leave teaching, while those who are successful and desire to continue teaching are more likely to commit to the fixed cost of obtaining a license and move to the higher-paying traditional public-school sector.

Our results contribute to the understanding of the impact that charter schools have on the quality of traditional public schools. Despite frequently voiced concerns that losing students to charter schools harms the quality of surrounding traditional public schools, the majority of prior studies (including research in Massachusetts) finds that charter-school growth has either null or small positive effects on the quality of local traditional public schools (Ridley and Terrier 2018, Cordes 2018, Imberman 2011, Bettinger 2005, Hoxby 2003, Booker et al. 2008, Bifulco and Ladd 2006, Winters 2012). Prior authors suggest that these effects derive from a combination of altering the school system’s available resources and by instilling competition for student enrolment.

Our results suggest that charter schools might also benefit traditional public schools by providing an alternative pathway for unlicensed teachers to enter the labour force and then sorting those who are successful in to traditional public schools. This pattern suggests that charter schools may create a positive externality for local public schools by increasing the average quality of the labour available to them.

References

Backes, B, and M Hansen (2015). “Teach for America impact estimates on non-tested student outcomes”, National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Bettinger, E P (2005). “The effect of charter schools on charter students and public schools”, Economics of Education Review 24(2): 133–47.

Bifulco, R, and H F Ladd (2006). “The impacts of charter schools on student achievement: Evidence from North Carolina”, Education Finance and Policy 1(1): 50–90.

Booker, K, S M Gilpatric, T Gronberg and D Jansen (2008). “The effect of charter schools on traditional public school students in Texas: Are children who stay behind left behind?”, Journal of Urban Economics 64(1):123–45.

Bruhn, J, S Imberman and M A Winters (2020). “Regulatory arbitrage in teacher hiring and retention: Evidence from Massachusetts charter schools”, NBER Working Paper 27607.

Chetty, R, J N Friedman and J E Rockoff (2014). “Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value added and student outcomes in adulthood”, American Economic Review 104(9): 2633–79.

Clark, M A, H S Chiang, T Silva, S McConnell, K Sonnenfeld, A Erbe, M Puma, E Warner and S Schmidt (2013). “The effectiveness of secondary math teachers from Teach for America and the teaching fellows programs”, US Department of Education.

Cordes, S A (2018). “In pursuit of the common good: The spillover effects of charter schools on public school students in New York City”, Education Finance and Policy 13(4): 484–512.

Cowen, J M, and M A Winters (2013). “Do charters retain teachers differently? Evidence from elementary schools in Florida”, Education Finance and Policy 8(1): 14–42.

Goldhaber, D, and M Hansen (2010). “Using performance on the job to inform teacher tenure decisions”, The American Economic Review 100(2): 250–5.

Hoxby, C M (2003). “School choice and school competition: Evidence from the United States”, Swedish Economic Policy Review 10: 11–67.

Imberman, S A (2011). “The effect of charter schools on achievement and behavior of public school students”, Journal of Public Economics 95(7-8): 850–63.

Kane, T J, J E Rockoff and D O Staiger (2008). “What does certification tell us about teacher effectiveness? Evidence from New York City”, Economics of Education Review 27(6): 615–31.

Ridley, M, and C Terrier (2018). “Fiscal and education spillovers from charter school expansion”, SEII Discussion Paper 2018.02.

Staiger, D O, and J E Rockoff (2010). “Searching for effective teachers with imperfect information”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 24(3): 97–118.

Winters, M A (2012). “Measuring the effect of charter schools on public school student achievement in an urban environment: Evidence from New York City”, Economics of Education Review 31(2): 293–301.

Endnotes

1 Author calculations using data from the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education School and District Profiles. https://profiles.doe.mass.edu/state_report/