Demands by policymakers and the general public for multinational enterprises (MNEs) to ‘clean up their supply chains’ and implement ‘responsible sourcing’ (RS) requirements for their suppliers in low- and middle-income countries have become widespread in recent years (ILO 2016, Bossavie et al. 2019, 2020, Koenig et al. 2021a, 2021b). These responsible sourcing policies typically take the form of ‘supplier codes of conduct’, requiring multinational enterprise suppliers to follow minimum standards on working conditions, such as wage floors, limits on hours worked, guaranteed benefits, or safety standards. MNEs privately enforce these requirements in several ways, most notably through third-party audits and turning the supplier codes of conduct into a contractual clause. MNEs also engage their suppliers in capacity building for compliance (Boudreau 2022). While the stated objective of these responsible sourcing policies is to benefit workers in low- and middle-income countries where MNEs source, there is still relatively little theoretical work and empirical evidence on their implications for worker welfare and distributional consequences among host countries.

In a recent paper (Alfaro-Ureña et al. 2022), we study the impact of responsible sourcing policies in the empirical context of Costa Rica, a middle-income country hosting hundreds of MNE subsidiaries across a wide range of economic activities, and where responsible sourcing policies have affected an increasing share of domestic producers. By the end of our sample in 2019, we find that close to 40% of domestic (non-MNE) output was produced by firms that were subject to active responsible sourcing contracts imposed by MNE subsidiaries. In this setting, we investigate whether responsible sourcing rollouts have discernible impacts on exposed suppliers and their workers (or are on average only ‘hot air’), and what the corresponding welfare implications are when taking into account both direct and knock-on effects on domestic labour markets and output markets.

The effects of responsible sourcing on workers are a priori ambiguous

We first develop a theoretical model of responsible sourcing to guide the analysis. We show that the overall effect of responsible sourcing on the welfare of workers in the host country is ex-ante ambiguous. On the one hand, responsible sourcing increases the payments to domestic factors of production embodied in exports, acting akin to an export tax that increases domestic welfare through a classic terms of trade effect. On the other hand, responsible sourcing standards also affect production for the domestic market, acting akin to a labour market distortion that increases the domestic price index.

This interplay of forces also depends on alternative hypotheses about the motivation behind responsible sourcing by MNEs and the market environment in which responsible sourcing is implemented. The impact on workers is, in theory, more beneficial when:

- more of the affected production is destined for exports;

- the increased cost of suppliers is passed through fully to MNEs;

- the demand for MNE output increases as a function of responsible sourcing (signal to consumers); or

- responsible sourcing is accompanied by direct productivity gains due to transfers of technology or expertise by the MNE.

Responsible sourcing policies are not just ‘hot air’

To conduct the empirical analysis, we construct a new dataset of responsible sourcing rollouts by MNEs with subsidiaries in Costa Rica. We combine these data with a rich combination of administrative data that allows us to track firms, their workers, and firm-to-firm transactions before and after responsible rollouts by MNE buyers over the period 2008-2019.

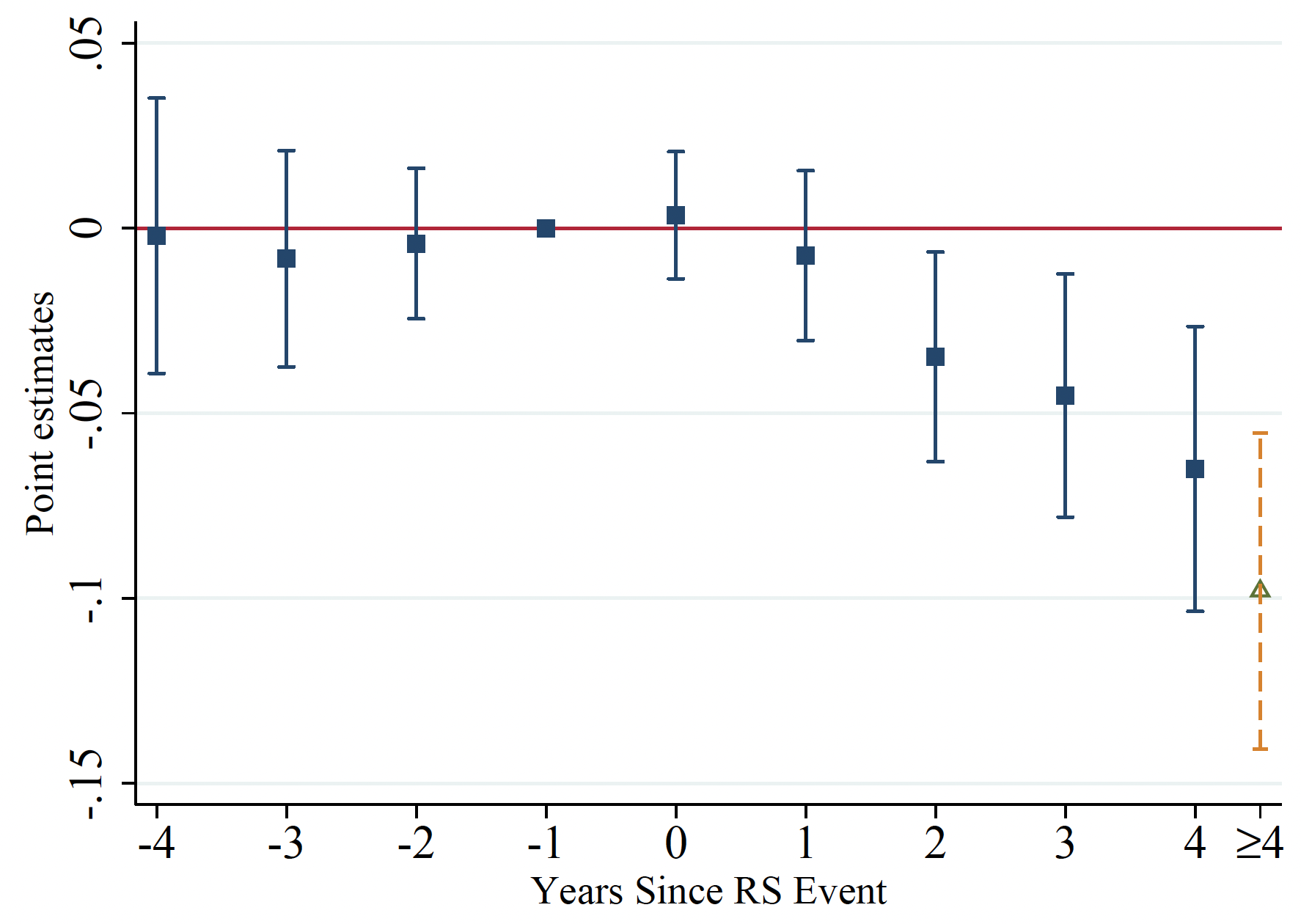

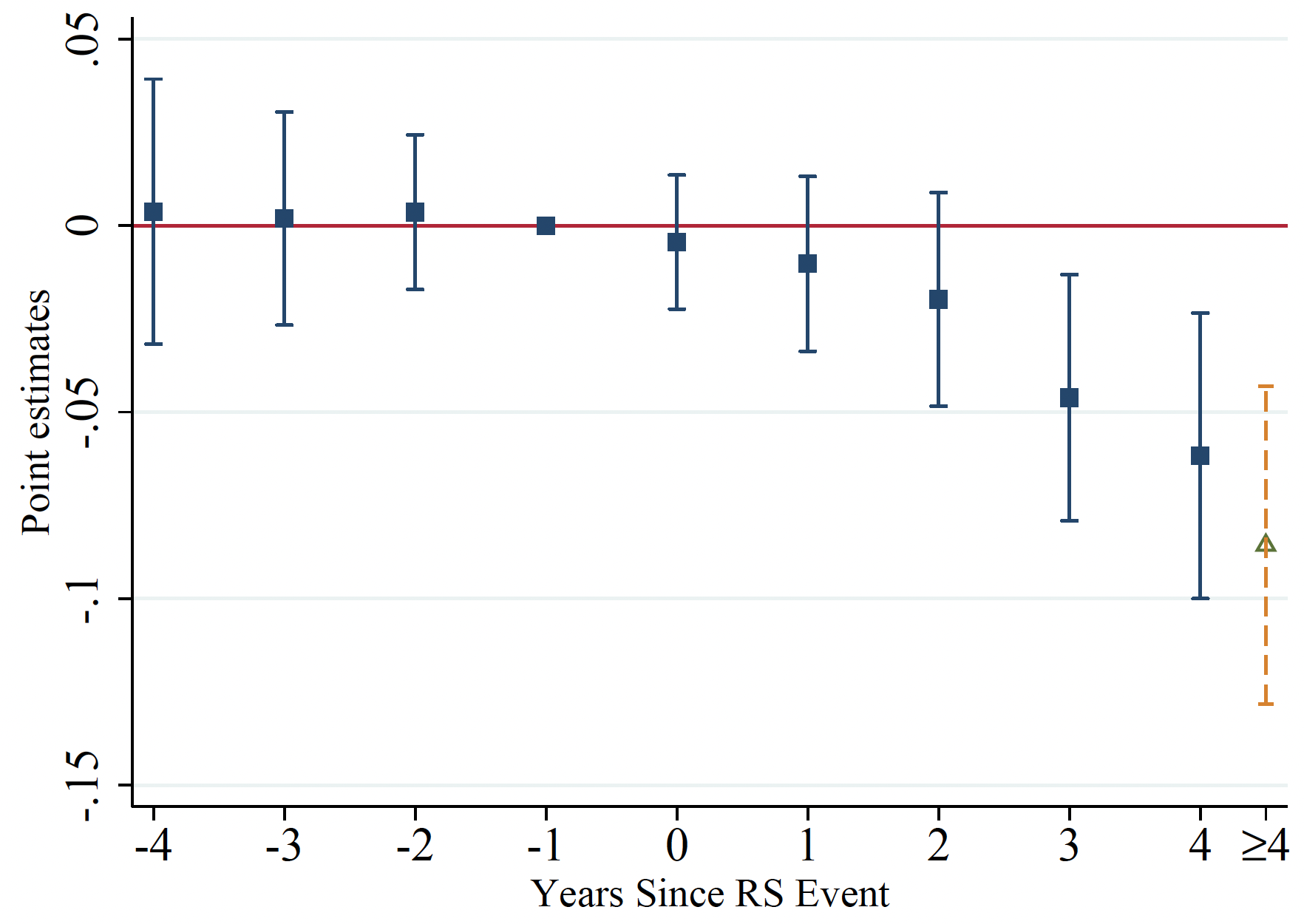

Using these data, we find that responsible sourcing rollouts significantly reduce total firm sales and employment at exposed (i.e. pre-existing) MNE suppliers. Four years after the responsible sourcing rollout, suppliers' sales and employment decline by roughly -7% and -6%, respectively (see Figures 1 and 2). These effects are concentrated among smaller suppliers in less regulated service sectors of the economy. The effects are also most pronounced when the responsible sourcing policies are implemented by MNEs headquartered in countries with higher management scores and stricter labour regulations.

Figure 1 Effect on log supplier total sales

Figure 2 Effect on log supplier employment

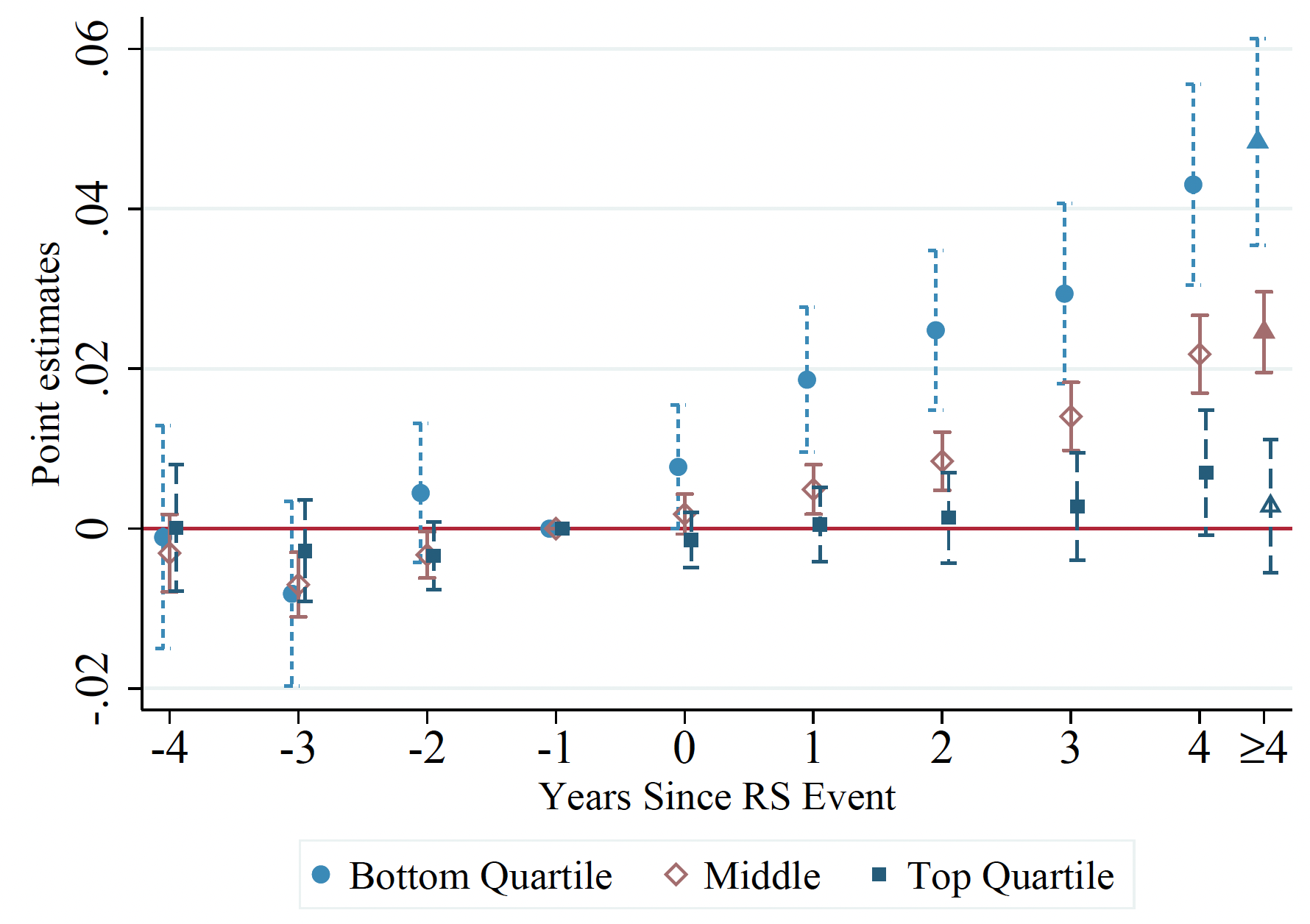

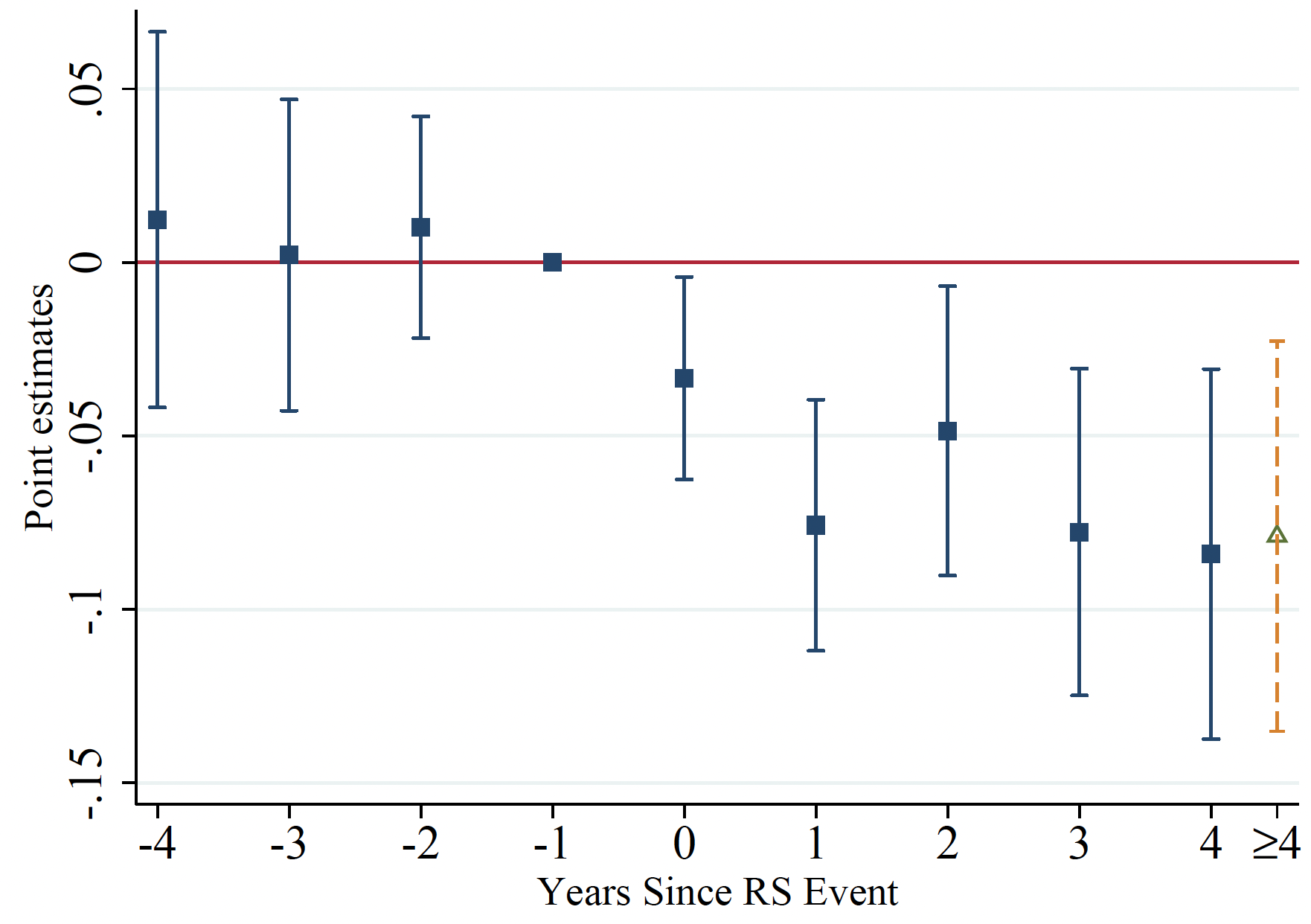

Using worker-level data, we find a roughly 1.5% average increase in monthly earnings for workers in exposed firms. This effect is driven by workers in the bottom quartile of initial earnings, for whom we find an average increase of 4.3% four years after the responsible sourcing rollout (see Figure 3). At the same time, the relative employment of initially low versus high-wage workers (bottom versus top quartiles) decreases by about 8% over the same period (see Figure 4).

Figure 3 Effect on log monthly earnings by worker type

Figure 4 Effect on log relative employment of low vs. high wage workers

Results using the firm-to-firm transaction data show that supplier sales to both non-responsible sourcing buyers and sales to the responsible sourcing MNE decrease post-rollout. The decline in the sales to the responsible sourcing MNE manifests both on the intensive margin (for the suppliers who continue supplying the responsible sourcing MNE) and extensive margin (as some exposed suppliers decide to stop selling to the responsible sourcing MNE).

Responsible sourcing led to modest country-level gains paired with meaningful distributional effects

The empirical evidence is qualitatively consistent with responsible sourcing rollouts leading to an increase in labour-related costs of production that is concentrated among initially low-wage workers. But this evidence, by design, is only able to capture the effects on exposed firms and workers relative to non-exposed ones in the wake of individual MNE responsible sourcing rollouts. These findings alone cannot speak to the overall effect on workers in the host economy, as the large extent of responsible sourcing-affected production in the data suggests that overall labour and output markets could be affected. To make progress, we use the empirical evidence to calibrate the model and use the model to evaluate the economy-wide implications of MNE responsible sourcing policies in Costa Rica over this period.

Combining our model with the database, we find that responsible sourcing policies increased labour-related costs for low-wage workers by on average roughly 12% and that only roughly 80% of that cost increase is passed through to MNE input costs. Overall, we find that responsible sourcing in Costa Rica led to a positive albeit minor aggregate gain in worker welfare both among initially low- and high-wage workers. These aggregate effects mask meaningful differences in the gains across exposed and non-exposed workers. The roughly one third of nationwide low-wage workers employed at suppliers to responsible sourcing MNEs before the rollout (‘exposed workers’) experience real income gains of around 8%. Those gains, however, are accompanied by knock-on effects on labour demand for low-wage workers and domestic consumption prices that decrease the real incomes, by roughly -3%, for the remaining majority of low-wage workers who are not directly exposed to responsible sourcing policies.

Conclusions

Our findings, both in the theory and the empirical analysis, highlight the need for caution when evaluating the implications of responsible sourcing standards by MNEs. While these policies can lead to tangible benefits among the group of workers directly exposed to the MNEs’ standards, the recent increase in the scale of responsible sourcing implementation (e.g. affecting close to 40% of domestic production in our setting) also warrants a careful analysis of the potentially unintended knock-on effects on overall labour and output markets, including effects on workers who may not be directly benefiting from better responsible sourcing standards.

It is also important to highlight some of the limitations of our study. First, as our model highlights, the implications of responsible sourcing on workers are context-specific. Second, Costa Rica is an upper-middle-income country compared to many poorer low-income countries where responsible sourcing has also been implemented in recent years. The responsible sourcing requirements that we study, both theoretically and empirically, in this context (improved compensation, benefits, working conditions) are likely distinct from other aspects of responsible sourcing in low-income countries, such as child labour bans. In theory, it would be a very different counterfactual exercise to instead ban a certain type of employment (e.g. Faber et al. 2017). These and other important differences in the institutional and labour market environments call for additional research in this area, and naturally demand some caution when extrapolating findings from one study to other contexts.

References

Alfaro-Ureña, L, B Faber, C Gaubert, I Manelici and J P Vasquez (2022), “Responsible Sourcing? Theory and Evidence from Costa Rica”, Working Paper.

Bossavie, L, Y Cho and R Heath (2019), “The Effects of International Scrutiny on Manufacturing Workers : Evidence from the Rana Plaza Collapse in Bangladesh”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9065.

Bossavie, L, Y Cho and R Heath (2020), “The effect of international scrutiny on manufacturing workers: Evidence from the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh”, VoxEU.org, 27 August.

Boudreau, L (2022), “Multinational Enforcement of Labor Law: Experimental Evidence on Strengthening Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Committees”, Working Paper.

Faber, B, B Krause and R Sanchez de la Sierra (2017), “Artisanal Mining, Livelihoods, and Child Labor in the Cobalt Supply Chain of the Democratic Republic of Congo”, Working paper.

ILO (2016), Decent Work in Supply Chains, International Labour Organization, Report IV.

Koenig, P, S Krautheim, C Löhnert and T Verdier (2021a), “Local Global Watchdogs: Trade, Sourcing and the Internationalization of Social Activism”, CESifo Working Paper 9068.

Koenig, P, S Krautheim, C Löhnert and T Verdier (2021b), “Globalisation and the economic geography of social activism”, VoxEU.org, 30 July.