The literature on optimal currency areas establishes a clear division of labour in the pursuit of macroeconomic stabilisation objectives (Mundell 1961, Kenen 1969, Farhi and Werning 2017). The objective of monetary policy is to limit fluctuations in average macroeconomic outcomes in response to symmetric shocks. Risk sharing instead should limit the dispersion in macroeconomic outcomes across the currency union by facilitating a geographically differentiated adjustment to asymmetric shocks.

An important, but so far under-explored, aspect in implementing this division of labour is that the impact of these macroeconomic stabilisation tools may interact. If monetary policy exerts a uniform impact on different members of a currency union, its role in limiting average economic fluctuations is unaffected by the role of risk sharing in limiting economic dispersion. But a growing literature has documented that monetary policy transmits unevenly, owing, for example, to differences in economic structures and initial conditions (e.g. Ampudia et al. 2018, Eichenbaum et al. 2018, Hauptmeier et al. 2020). This, in turn, may render the impact of monetary policy dependent on the risk-sharing architecture of a currency union. For instance, if the tax and transfer system systematically reallocates funds from less to more affected regions, the aggregate impact of a monetary policy tightening may be different than in a scenario without this type of fiscal risk sharing.

In a recent paper, we provide empirical evidence on the relevance and nature of these interactions, based on regionally disaggregated data for the euro area (Hauptmeier et al. 2022).

Interaction between risk sharing and monetary policy

As a first step, we rely on the well-established framework by Asdrubali et al. (1996) to estimate the degree and composition of risk sharing across regions within individual euro area countries.

The methodology allows us to estimate the amount of risk shared through the factor market, fiscal, and credit market channels. We then feed these estimates into a local projections model to study how the risk-sharing intensity affects the transmission of monetary policy shocks to the real economy.

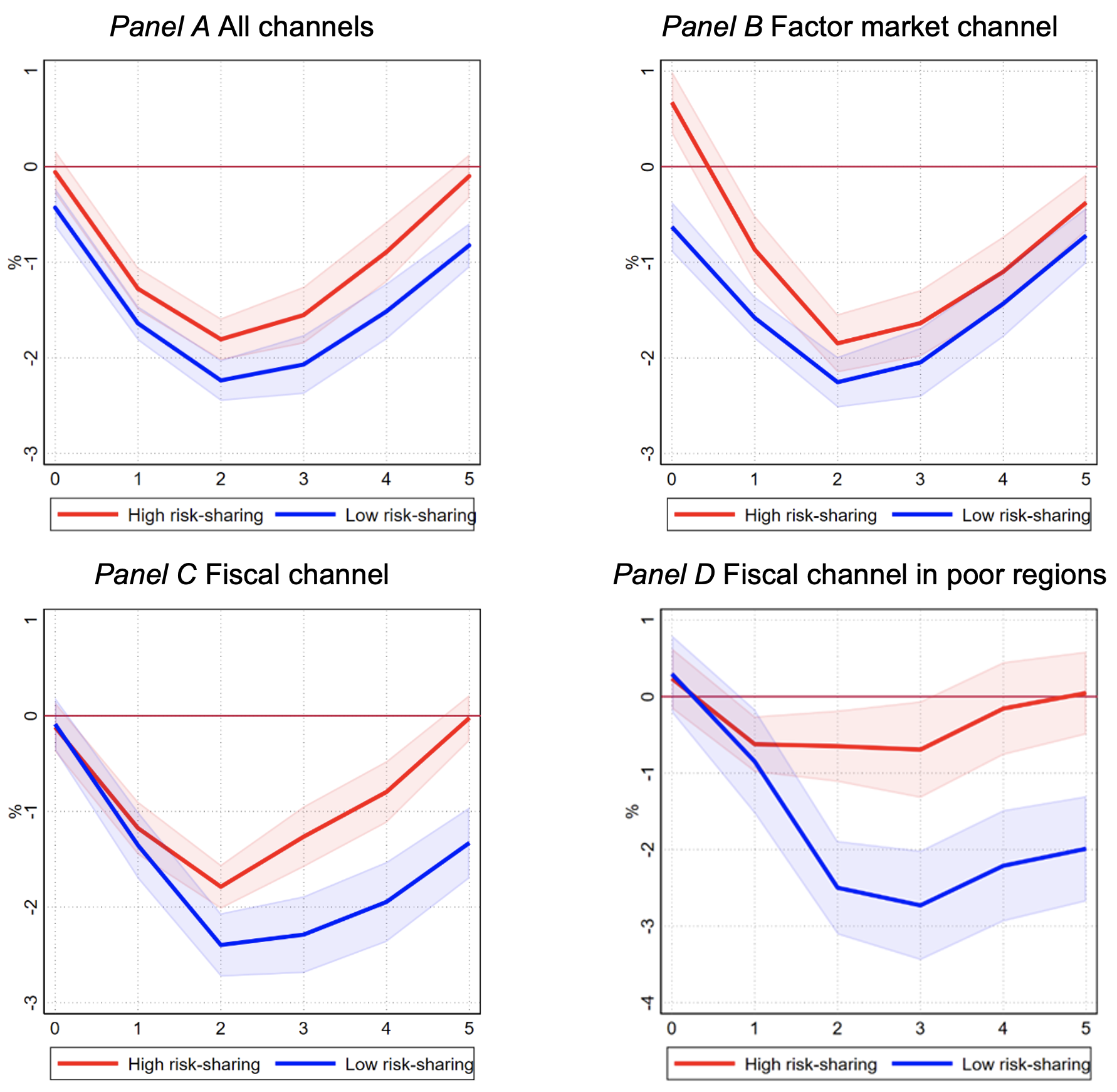

Our results suggest that risk sharing dampens the real effects of monetary policy. Figure 1, Panel A presents the response of regional output to a 100 basis point interest rate hike for different percentiles of the risk-sharing distribution. In the upper quartile of the distribution, regional output decreases by 1.9% after two years, whereas in the lower quartile the corresponding contraction is 0.4 percentage point deeper.

Figure 1 Monetary policy effects on output conditional on risk sharing intensity

Note: Vertical axes refer to the impact of a 100 basis point rate hike on regional GDP (in %). Horizontal axes refer to the horizon of the impulse response functions (IRFs) (in years). Solid lines denote point estimates and shaded areas denote 90% confidence bands. Red (blue) lines depict the estimates for the upper (lower) quartiles of risk-sharing intensity for panels a) to c) and deciles of risk-sharing intensity for panel d). Poor regions are defined as the lowest decile of the GDP distribution.

Disentangling private and public risk sharing effects

Regarding individual channels, both private risk sharing, via factor and credit markets, as well as public risk sharing, cushion the impact of a monetary policy tightening. However, the channels differ in their time profiles. Private risk-sharing channels tend to dampen the monetary policy shock contemporaneously and up to one year after the shock (Figure 1, Panel B).

Fiscal risk sharing instead mitigates the economic consequences of a rate hike over longer horizons (Figure 1, Panel C). Public and private risk-sharing channels therefore emerge as complements, in that they operate at different time horizons.

Heterogeneity across regions

The interaction between risk sharing and monetary policy may vary between more or less prosperous regions. For instance, the stabilisation role of fiscal instruments might be reinforced if net transfers are targeted towards poorer regions, which would tend to be populated by households with a larger propensity to spend. To explore this aspect, we rely on the quantile fixed effects estimator of Machado and Santos Silva (2019) to estimate the impact of exogenous changes in monetary policy across the regional GDP distribution. Our quantile regression analysis reveals pronounced differences in the degree to which fiscal risk sharing especially determines the transmission of monetary policy to rich versus poor regions. With weak fiscal risk sharing, GDP in poor regions does not only exhibit a strong contraction, but the impact proves highly persistent. By contrast, with strong fiscal risk sharing, the GDP contraction in poor regions is markedly shallower and turns insignificant at longer horizons (Figure 1, Panel D). Fiscal risk sharing thus emerges as particularly instrumental in pre-empting long-lived hysteresis effects of monetary policy in regions with weak economic performance already prior to the shock.

Implications

These findings offer relevant insights for the debate on the institutional setup of the Economic and Monetary Union (Weder di Mauro et al. 2018). First, they suggest that heterogeneity in the capacity to absorb shocks via fiscal and market-based channels could contribute to an uneven transmission of monetary policy across jurisdictions. Second, the results point to the benefits of fiscal risk sharing in mitigating the tendency for regional economic divergence to intensify in policy tightening cycles. Third, they indicate that changes to the risk-sharing architecture of an economy may have a major bearing on the aggregate effects of a given change in monetary policy stance.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Central Bank.

References

Ampudia, M, D Georgarakos, M Lenza, J Slacalek, O Tristani, P Vermeulen and G L Violante (2018), “Household Heterogeneity and the Transmission of Monetary Policy in the Euro Area”, VoxEU.org, 14 August.

Asdrubali, P, B Sorensen and O Yosha (1996), “Channels of Interstate Risk Sharing: United States 1963–1990”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111(4): 1081–1110.

Eichenbaum, M, S Rebelo and A Wong (2018), “State-Dependent Effects of Monetary Policy: The Refinancing Channel”, VoxEU.org, 2 December.

Farhi, E and I Werning (2017), “Fiscal Unions”, American Economic Review 107(12): 3788–3834.

Hauptmeier, S, F Holm-Hadulla and K Nikalexi (2020), “Monetary Policy and Regional Inequality”, VoxEU.org, 22 April.

Hauptmeier, S, F Holm-Hadulla and T Renault (2022), “Risk Sharing and Monetary Policy Transmission”, Working Paper Series 2746, European Central Bank.

Kenen, P B (1969), “The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas : An Eclectic View”, in R A Mundell and A K Swoboda (eds.), Monetary Problems of the International Economy, University of Chicago Press.

Machado, J A F and J M C Santos Silva (2019), “Quantiles via Moments”, Journal of Econometrics 213(1): 145–73.

Mundell, R A (1961), “A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas”, The American Economic Review 51(4): 657–65.

Weder di Mauro, B, J Zettelmeyer, H Rey, N Véron, P Martin, F Pisani, C Fuest, P Gourinchas, M Fratzscher, E Farhi, H Enderlein, M Brunnermeier and A Bénassy-Quéré (2018), “Reconciling Risk Sharing with Market Discipline: A Constructive Approach to Euro Area Reform”, CEPR Policy Insight 91, 17 January.