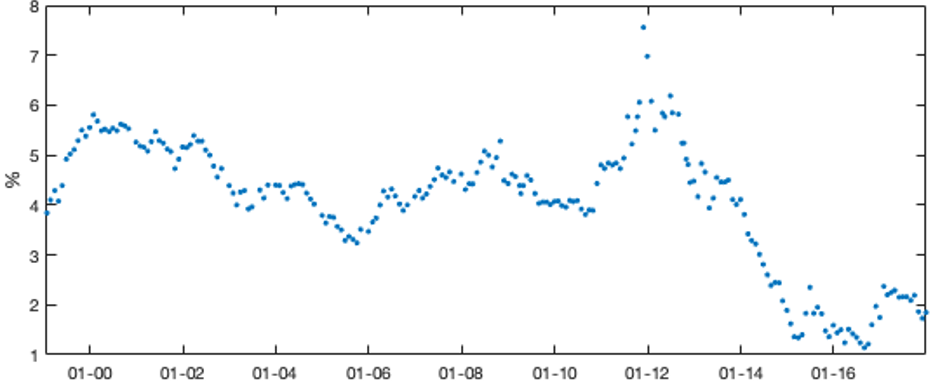

The euro area’s sovereign debt crisis forced several of its member states into a macroeconomic adjustment programme in order to maintain or regain access to the international capital markets. Difficulties with capital market access manifest themselves through rising costs of public debt issuance. Although the crisis has abated and countries have completed their adjustment programmes, we still observe occasional spikes in the rates at which new public debt is issued. If issuance rates behaved as smooth and predictable functions of the ratio of public debt over GDP, they would serve as useful warning devices of fiscal profligacy. However, this is not how issuance rates behave. While on average they tend to be higher for countries with higher debt ratios, they are highly variable and quite unpredictable. This has been the case for Italy, for example (see Figure 1),1 where annual yields on newly issued 10-year debt reached almost 8% end of 2011, up from around 6% at the previous auction. Indeed, we know that financial markets can react very abruptly and, hence, each auction of new debt carries some potential risk for the issuer. This risk cannot be entirely avoided, because auctions are planned quite long before they take place and cancelling them has a highly damaging effect on the issuer of the debt. Moreover, there may be no alternatives to bridge the issuer’s cash needs.

Figure 1 Average accepted yields on Italian 10-year debt issues

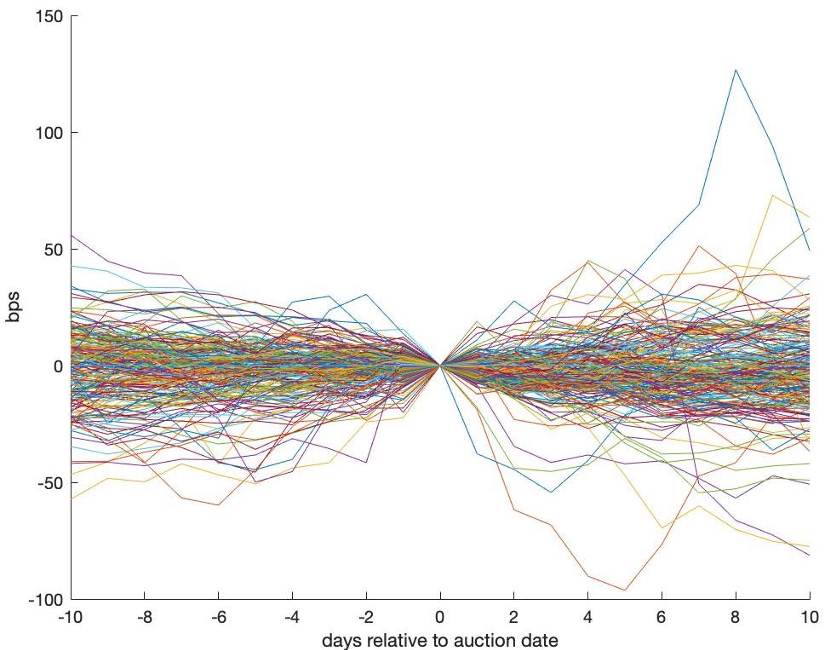

The potential risk associated with debt auctions is further illustrated in Figure 2,2 which depicts secondary market yields on 10-year Italian debt relative to the secondary market yield on days on which new 10-year Italian debt is auctioned. Yield movements around auctions can be quite large over the sample period since 1999, ranging from a fall of 1% to a rise of around 1.3%. Since primary and secondary market yields on similar or identical instruments are highly correlated, secondary market yield increases prior to an auction would push up yields at which new debt is issued, thereby driving up debt-servicing costs. While in most instances yield movements are limited around auctions, Figure 2 shows that substantial yield increases cannot be excluded, and it is these increases that could even force DMOs to withdraw an auction.3 In addition, there is the danger of contagion to other countries in the euro area if a country experiences trouble placing its new debt.

Figure 2 Yield movements on Italian 10-year secondary market debt around new debt issues

Note: the figure depicts for a 20-day window in basis points the secondary market yields on 10-year Italian debt relative to the secondary market yield on days 0 on which new 10-year Italian debt is auctioned.

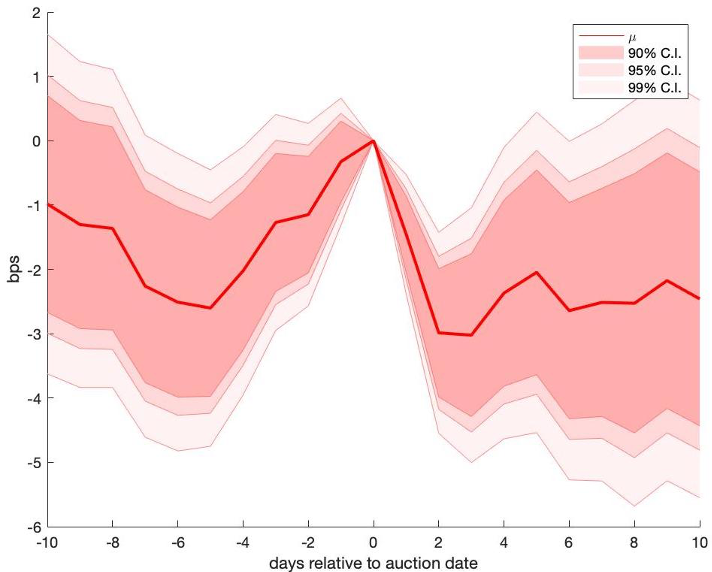

Figure 2 shows that yields can go up or down prior to and after an auction. However, from the figure we cannot discern the average secondary market yield changes around new debt auctions. These would not be so informative about crisis situations, but they would provide information on how debt-servicing costs are on average affected by secondary market yield movements around auctions. Research by Fleming and Rosenberg (2007), Lou et al. (2013), Beetsma et al. (2016) and Sigaux (2018) shows that, in the run-up to a new public debt auction, secondary market yields on existing debt with a high pay-off correlation with the instrument on issue tend to rise, while they tend to revert to their original level after the auction. This phenomenon is termed the ‘auction cycle’. Auction cycles may arise because, prior to a new debt auction, the primary dealers who buy the debt before passing it on to other users need to free up space in their trading portfolios, which they optimally do by reducing their position in instruments closely substitutable to the instrument on auction. Alternatively, prior to the auction they short highly substitutable instruments in order to hedge the risk from taking the auctioned debt on their balance.

Figure 3, which is based on our work in Van Spronsen and Beetsma (2019), depicts the average auction cycle for the Italian auctions in our sample. Date zero is the day of an auction. The central line is the average deviation in basis points of the 10-year secondary market yield from its yield on the auction day across all Italian 10-year debt auctions since 1999. The shaded areas indicate the confidence regions. On average, Italian secondary market yields increase around 2.5 basis points during the week before a new issue. In 10% of the cases the increase is almost or more than twice as large. While these numbers may seem small, our calculations reported below show that even these average yield movements around auctions, though falling way short of causing a liquidity crisis, imply non-negligible increases in annual debt-servicing costs.

Figure 3 Average secondary market yield movements around auctions

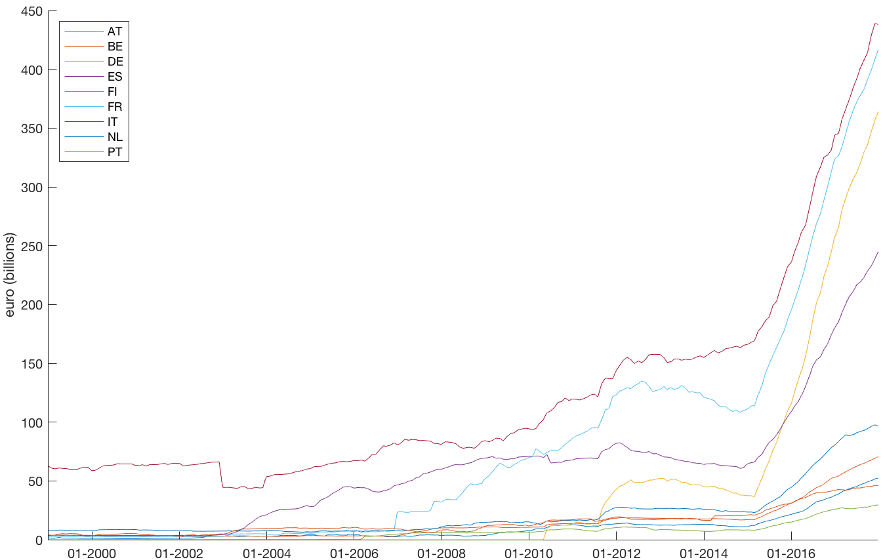

Notes: While macroeconomic adjustment programmes are targeted at countries that lost or are in danger of losing capital market access, the ECB’s unconventional monetary policy measures aim to improve the euro area-wide conditions for the transmission of monetary policy. The European System of Central Banks (ESCB) spent almost 2,900 billion euros on asset purchases between mid-2009 and the end-of-2018, when the purchases were temporarily halted. These resumed at a slow pace in November 2019. The public sector purchases programme (PSPP), which started in March 2015, is by far the largest. As a result of the PSPP, euro area sovereign debt holdings by national euro area central banks have surged – see Figure 4. Although the ECB is not allowed to trade in the primary market for public debt, and claims not to affect price formation in this market4, our new research suggests that the sovereign debt purchases by the ESCB do affect the yields at which new debt is issued, by dampening the auction cycles in the secondary markets.

Figure 4 National central bank holdings of euro area sovereign debt

We find strong econometric evidence of cycles arising from both domestic and foreign auctions. The amplitude of the cycles tends to increase with current general market volatility. We also show that the cycles originating from domestic auctions and the role of market volatility for these cycles are largest for the euro area member states with the lowest credit ratings. Moreover, debt issuance by these countries generates the strongest cross-border effects on secondary markets. Further, and most relevant for our study, we find evidence that larger amounts of ESCB sovereign debt purchases in a month tend to dampen both the average size of the cycles associated with the domestic and foreign auctions, as well as the positive effect of market volatility on the magnitude of these cycles.

Assuming that primary-market yields move roughly in lockstep with secondary market yields, we construct back-of-the-envelope calculations for the effect of auction cycles on debt-servicing costs, and by how much how these cycles are moderated by the European System of Central Banks’ (ESCB’s) sovereign purchases. Such a calculation for France, a country with a relatively low credit rating in the sample, suggests that the cycle associated with all domestic (foreign) 10-year auctions raises annual debt-servicing costs by around €110 million (€5 million). A one-standard deviation increase in market volatility raises these figures by around €120 million (€11 million), while typical central bank purchasing activity lowers these costs by roughly €25 million (€2 million) for cycles generated by domestic (foreign) auctions.

Our findings carry potential policy implications. First, in view of the cross-border spillover effects of auctions, it may be beneficial for public finances if the euro area DMOs coordinate their issuance calendars so as to minimise these effects, i.e. debt issuances by different countries should not be too close together in time.

Second, the detected effects of the ESCB’s sovereign debt purchases on the auction cycles should not necessarily be interpreted as incompatible with the objective of minimising their effect on primary and secondary sovereign debt markets. Auction cycles are the result of a market friction in the sense that a limited set of primary dealers with limited resources need to first absorb the newly issued debt. The ESCB interventions help to dampen temporary and unwarranted yield increases caused by this friction, thereby dampening unwarranted increases in debt-servicing costs. In addition, the temporary yield increases associated with auction cycles disappear after a few days. Hence, while the amplitude of the auction cycle is affected by the ESCB’s purchases, the effect of these purchases disappears after a few days when the cycle has died out.

Third, since increases in market volatility affect the secondary sovereign debt markets of all euro area members, concentrating ESCB purchases during periods of high market volatility would further reduce unwarranted increases in debt-servicing costs, without structurally affecting public debt yields and without giving advantages to specific countries.

Moreover, although this is speculative, and more research is needed to underpin such a conclusion, the ESCB purchases could potentially reduce risks of extreme yield movements around new debt auctions, risks that might not necessarily be caused by fundamentals, but that are likely relatively high during periods of high market volatility.

References

Beetsma, R, M Giuliodori, F De Jong, and D Widijanto (2016), “Price Effects of Sovereign Debt Auctions in the Eurozone: The Role of the Crisis”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 25: 30-53.

Fleming, M, and J Rosenberg (2007), “How Do Treasury Dealers Manage Their Positions?”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, 299.

Lou, D, H Yan, and J Zhang (2013), “Anticipated and Repeated Shocks in Liquid Markets”, Review of Financial Studies 26: 1891-1912.

Sigaux, J-D (2018), “Trading ahead of Treasury Auctions”, ECB Working Paper no. 2208.

Van Spronsen, J, and R Beetsma (2019), “Unconventional Monetary Policy and the Auction Cycles of Eurozone Sovereign Debt”, CEPR Discussion Paper no.14099.

Endnotes

[1] The figure is based on auctions of 10-year debt, because this generally is the most liquid and most-frequently auctioned bond.

[2] Secondary market data are for outstanding bonds with a remaining maturity of 10 years.

[3] For this reason, DMOs keep a close eye on secondary market conditions when setting the terms of a new debt issue. It is important to notice that yield fluctuations around auction dates are not necessarily more volatile than yield fluctuations outside those periods. In particular, we would not expect systematic differences in volatility if the flow of news is unrelated to the auctions themselves.

[4] In particular, the ECB states that “We do not buy government bonds in the primary market, which is explicitly forbidden under Article 123. And neither do we act in the secondary market in a way which could be perceived as equivalent to acting in the primary market.” See https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2016/html/sp160623.en.html.