It is widely accepted that a key determinant of the poverty of Africa is the under-provision of public goods. This is typically attributed to the lack of fiscal resources and, to the extent these resources are present, their miss-allocation. The underlying causes of both the dearth of resources and the failure to convert them into public goods are conventionally ascribed to weak state capacity (Besley and Persson 2011), the reluctance of people to concede resources to states with a history of miss-allocating public resources (Moore et al. 2018), structural factors such as natural resource and aid dependence, and the reluctance of political elites to set in motion processes that might induce greater accountability (Acemoglu and Robinson 2019, Weigel 2020).

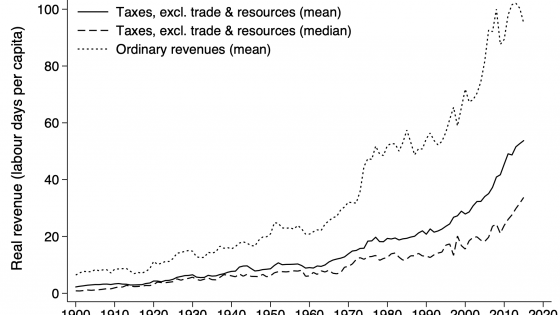

In a new paper (Robinson 2022), I propose a new explanation for why tax revenues are so low in Africa (see Albers et al. 2020 for a historical perspective). There is robust evidence that weak capacity, lack of accountability, and resource and aid dependence of African states are part of the explanation (Moore et al. 2018). But I argue that the problem is not only weak capacity or tax evasion; it is what I call tax aversion (see Besley et al. 2015 on tax evasion). Even if states were accountable, non-corrupt, and had the capacity to turn tax revenues into public goods, people do not necessarily want to see this happen. Africans are averse to taxation for reasons that have nothing to do with the typical mechanisms proposed. Rather, their aversion stems from deep-seated attitudes towards taxation related to historic social contracts in Africa.

To illustrate the extent of tax aversion, I use data from Round 10 of the Afrobarometer. To start with a concrete case, consider the attitudes of Sierra Leoneans to taxation. Participants were asked: “Do you think that the amount of taxes that ordinary people in Sierra Leone are required to pay to the government is too little, too much, or about the right amount?” A mere 10–15% of Sierra Leoneans think the government should tax more, while 47% of rural and 24% of urban people think it should tax less. An overwhelming majority of Sierra Leoneans oppose higher taxes, even though it is widely agreed that the country’s public service provision is very poor.

There are several mechanisms which help account for this pattern. An obvious one is that people may not believe that taxes will be allocated to public services, but rather misappropriated. This is clearly part of the picture and evident from other answers. For instance, only 7% of Sierra Leoneans believe that there is no corruption connected to “the president and officials in his office” (Question 42A). Only 5% of people think there is no corruption within the civil service (42C). With respect to opinions about the performance of the government, perspectives are equally negative: 83% of people think the government is doing badly at “improving the living standards of the poor” (50B), while 62% think they are doing badly at “improving basic health services” (50G). In fact, around 60–70% of people believe the government is performing badly at providing public goods. In addition, a mere 11% of people think it is “easy” to “find out how government uses the revenues from people’s taxes and fees” (46B). No wonder Sierra Leoneans don't want to pay taxes.

But this is not the whole story. People were also asked: “Which of the following statements is closest to your view? Statement 1: It is better to pay higher taxes if it means that there will be more services provided by government. Or statement 2: It is better to pay lower taxes, even if it means there will be fewer services provided by government.”

When asked if they would favour higher taxes if they were sure the money would be spent on public goods and services, 41% of Sierra Leoneans preferred lower taxes and fewer services to higher taxes and more services. This total ranges from 48% of rural residents to 33% of people living in urban areas. Close to a majority would rather have lower taxes and fewer services! This is the general position across 18 countries in Africa according to the Afrobarometer data, which finds that 42% of people favour lower taxes and fewer services.

The evidence from this question is not consistent with the traditional arguments about state capacity or lack of accountability, but it can be explained by the nature of historical social contracts. The fundamental fact about historic African polities was their small scale. Southall (1970) notes that “before they were cut short by the nineteenth century onslaught of the Western imperial powers, the indigenous societies and autonomous polities of Africa had to be counted in the thousands”. According to Henn and Robinson’s (2021) calculation, no more than 30% of Africans lived in states during the Scramble for Africa.

Why did Africa not develop the type of large centralised and bureaucratised states seen in Eurasia or the Americas? The most influential explanation for this is from Vansina (1990), who suggests that “Africans grappled in an original way with the question of how to maintain local autonomy paramount, even while enlarging the scale of society”. In his theory of Central African political development, people created institutions in order to “safeguard the internal autonomy of each community”. Though familiar pressures – such as population growth or the need to provide public goods – led to the “birth of some chiefdoms, even kingdoms”, it mostly “led to the birth of new forms of association to safeguard the autonomy of the basic community in a time of expansion”. Vansina concludes that “the ability to refuse centralization while maintaining the necessary cohesion among a myriad of autonomous units has been the most original contribution of western Bantu tradition to the institutional history of the world”.

That Africans “refused” centralisation historically is a key to understanding patterns in the Afrobarometer: when states formed, they were nearly all hybrid institutions. The most salient example of these is what Southall (1956) called “segmentary states”, which had “limited jurisdictions” that rarely involved taxation. This was because the institutional designs of such states were intended to “safeguard the internal autonomy” of the community and avoid the type of monitoring and penetration of society that would have arisen from a fiscal system.

The normative attitudes underlying such social contracts were intensified by the experience of alien and arbitrary state authority during the colonial period. Even today, the phrase in Igbo for a civil service position is ‘Olu oyibo’ or ‘Oru oyibo’, meaning ‘white man’s job’. They were perpetuated after independence by the state-building strategies adopted in different African countries, which in many ways had to adapt themselves to the underlying realities of these attitudes. The problem of building new post-colonial social contracts was exacerbated by the immense heterogeneity of states faced with aggregating very different types of social contracts into a national one.

An important implication of this analysis is that building fiscal systems in Africa is not simply a technical or human resources problem; it is a political one. There is no doubt that the world and the needs of Africans have changed immensely since their social contracts were formed, and that they need adapting and re-forging in the current context. Spaces where a legitimate process of deliberation and negotiation can take place now need to emerge. This happened in Botswana in the 1960s and 1970s, and in Somaliland since the 1990s, but has otherwise been all too rare.

You can read more about this topic in the VoxDevLit on "Taxation and Economic Development".

References

Acemoglu, D and J A Robinson (2019), The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies and the Fate of Liberty, New York: Penguin.

Albers, T, M Jerven and M Suesse (2020), “On the development of fiscal capacity: New insights from African data”, VoxEU.org, 22 November.

Besley, T, A Jensen and T Persson (2015), “Norms of tax compliance”, VoxEU.org, 12 February.

Besley, T and T Persson (2011), Pillars of Prosperity, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Henn, S J and J A Robinson (2021), “Africa’s Latent Assets”, NBER Working Paper No. 28603.

Moore, M, W Prichard and O-H Fjeldstad (2018), Taxing Africa: Coercion, Reform and Development, London: Zed Books.

Robinson, J A (2021), “Tax Aversion and the Social Contract in Africa”, NBER Working Paper No. 29924.

Southall, A (1956), Alur Society: A Study in Processes and Types of Domination, Cambridge: W Heffer, 231–234.

Southall, A (1970), “Stratification in Africa”, Essays in Comparative Stratification, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Vansina, J (1990), Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 101, 119, 237.

Weigel, J (2020), “The Participation dividend of taxation: How citizens in Congo engage more with the state when it tries to tax them”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(4): 1849–1903.