Since the onset of economic reforms in the 1980s and following the liberalisation process in the 1990s, the most salient trait of Chinese economic development has been the swift industrialisation that has transformed China into the largest industrial power worldwide (Song et al. 2011). But the booming manufacturing sector may have obscured a more subtle change: China is currently undergoing a rapid tertiarisation process, with its service industries growing as a share of GDP at the expense of both agriculture and manufacturing. Rapid tertiarisation could be a symptom of incipient Baumol’s disease, that is, as Chinese consumers get richer owing to increased productivity in manufacturing, they demand more luxury goods and services. This would be a bad omen for future growth in China. If the share of the service sector grows, but the productivity of this sector is intrinsically stagnant, average GDP growth is destined to slow down. Baumol’s disease is already a primary concern for mature economies (e.g. Duernecker et al. 2017, 2018). However, the concern is also spreading to China in the wake of the recent economic slowdown, as officially acknowledged by Liu He, the Chinese vice premier, in a keynote speech at the World Internet Conference on 26 September 2021.

Yet, the importance and potential complexity of the tertiarisation process are still underappreciated. Most existing economic research focuses on the manufacturing sector and its dynamics. This is partly due to data availability. China has a detailed census of manufacturing firms as well as a National Business Survey that covers all manufacturing plants above a threshold size. There is no comparable survey for service firms. Moreover, measuring productivity in the service sector is notoriously difficult.

Recent trends in China’s service sector

In a recent paper (Chen et al. forthcoming), we provide an anatomy of China’s growing service sector. Using official statistics on sectoral aggregates, we document the rapid growth of service industries providing inputs to the industrial sector, which we label producer services. However, producer services are not the only driver of tertiarisation. We also observe a boom in consumer services, i.e. the service industries that improve consumers’ access to goods (e.g. retail or restaurants) or provide services that are directly consumed by households (e.g. recreation, health, and community services). In contrast, we do not find that government-provided services (public services) play a key role in China’s tertiarisation process. More importantly, we document significantly higher growth in productivity in producer services and consumer services relative to the industrial and secondary sectors. This observation alleviates concerns about the risk of Baumol’s disease in the Chinese economy.

Specifically, we document the following trends:

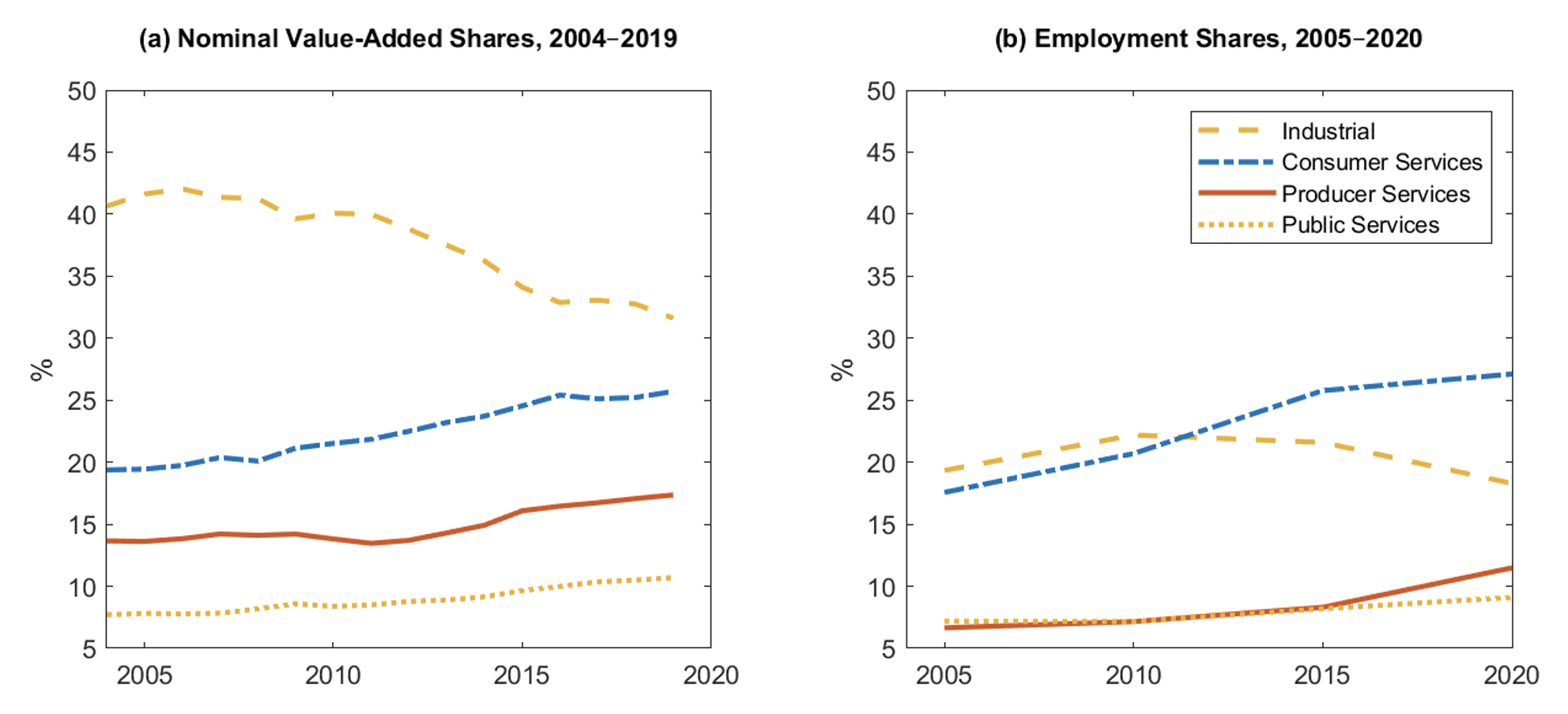

- The tertiary sector is expanding relative to the secondary and industrial sectors in terms of both value-added and employment shares (see Figure 1).

- The three subsectors of the tertiary sector we constructed—producer services, consumer services, and public services—feature fairly balanced growth in terms of value-added (see panel (a) of Figure 1). However, the employment shares of consumer services grew faster than those of producer and public services (see panel (b) of Figure 1).

- The relative prices of all services grew over time.

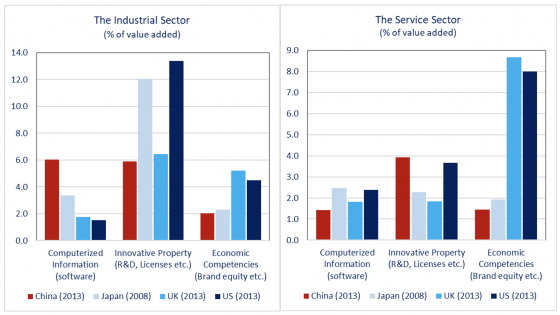

- Skill upgrading has been stronger in the service sector (especially for producer services, but also for consumer services) than in the industrial and construction sectors.

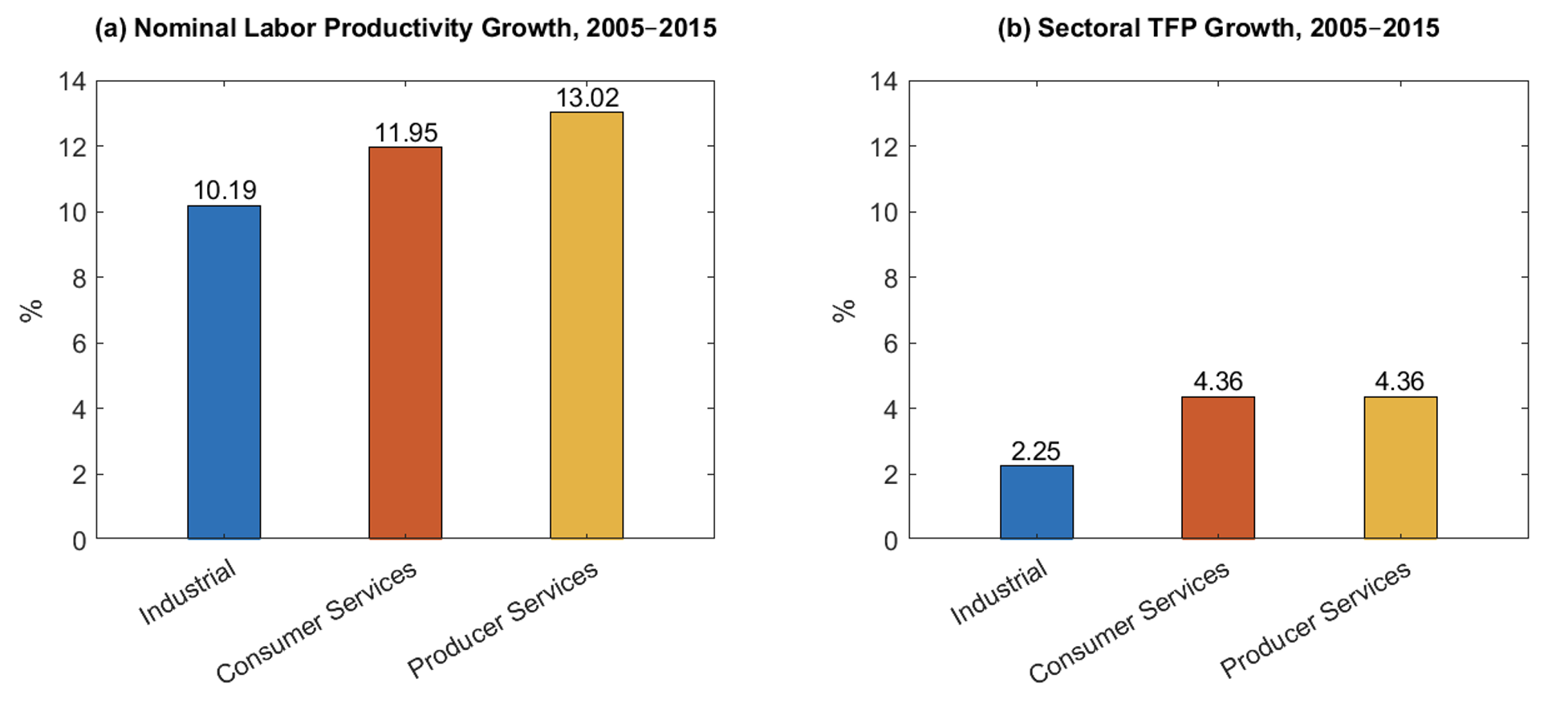

- During 2005-15, productivity has grown more quickly in the consumer and producer service sectors than in the industrial sector. The results are robust to different methods of estimating productivity growth, including the procedure proposed by Fan et al. (2022) that gets around measurement issues for the price index of services.

Figure 1 Sectoral value-added shares and employment shares

Methodology

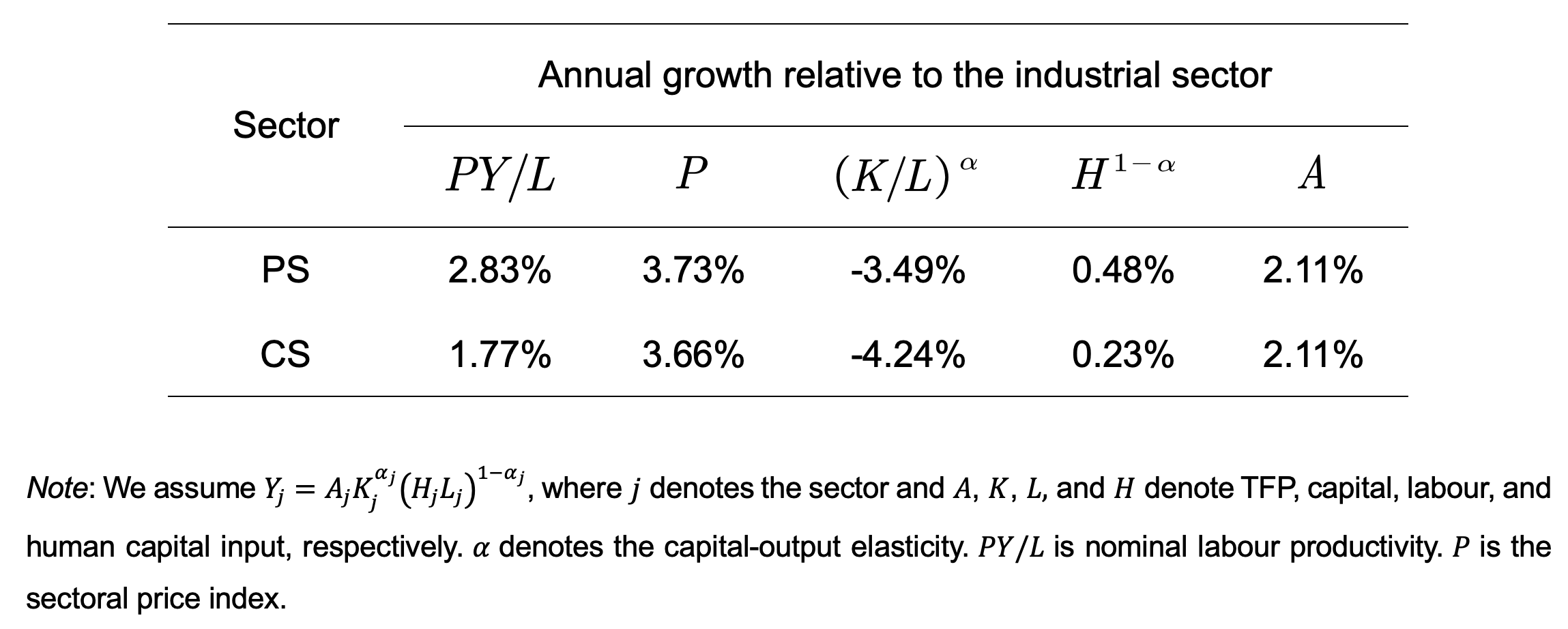

We postulate a set of sectoral production functions and decompose the growth rate of nominal labour productivity into the growth rates of the sectoral price level, sectoral total factor productivity (TFP), and factor inputs – a weighted average of the growth rates of the capital-labour ratio and human capital.

As usual, we cannot directly measure TFP, and we calculate it as a residual.

We start with nominal labour productivity (see panel (a) of Figure 2). Both producer services (13%) and consumer services (12%) have higher growth in nominal labour productivity than the industrial sector (10%). In Table 1, we express sectoral labour productivity as the differences between producer or consumer services and the industrial sector. An important part of the nominal differences is explained by changes in relative prices. However, this is not the whole story. Service industries also experience a less capital deepening and (as an offsetting force) higher growth in human capital input. Ultimately – perhaps surprisingly – we find TFP growth in both producer services (4.4%) and consumer services (4.4%) to exceed TFP growth in the industrial sector (2.3%) (see panel (b) of Figure 2). The gap is similar in the case of consumer services and producer services (+2.1% annually).

Figure 2 Sectoral nominal labour productivity and TFP growth, 2005–2015

Table 1 The decomposition of sectoral labour productivity growth relative to the industrial sector, 2005–2015

The joint observation of higher sectoral TFP growth in service industries and an increase over time in the relative price of services suggests a potentially important role in non-homothetic demand. Namely, services appear to be luxuries. However, we also document the important role of supply factors. Even though services (especially producer services) already had the highest human capital intensity in 2005, they also experienced high growth in this input. This suggests that service industries were the main destination for the increasingly educated Chinese labour force. Last but not least, TFP growth has been high in services – even higher than in the industrial sector. This finding runs against the traditional view that the ultimate driver of the development process is the growth of productivity in manufacturing, while tertiarisation is a corollary of development that merely results from income effects. It is instead in line with the findings of Fan et al. (2022) for India between 1987 and 2011. Human capital and TFP growth jointly account for a differential annual growth in value-added per worker of +2.7% for producer services and +2.4% for consumer services.

These gaps partially offset the lower physical investment in service industries.

A new stage of development?

Overall, our findings suggest that China’s development process has entered a new stage in which services and the domestic market play a significantly more important role than in the past. If tertiarisation is no mere consequence of rapid income growth but a result of productivity growth in services, the growth process can prove resilient to Baumol’s disease.

Should we expect this trend to continue? The growing tension in international relations is likely to raise barriers to international trade. This might further speed up the ongoing structural transformation by enhancing the importance of the domestic market and nontradable goods. The consolidation of an urban middle class is also likely to sustain the growing demand for services in the coming years. Recent research from Beerli et al. (2020) shows that demand forces are an important driver of the direction of technical change. Thus, the growing demand for services will likely trigger additional productivity growth in the service sector. Moreover, to the extent these services are local in nature, the benefits of growth can become even more skewed in favour of large cities. Finally, service-led growth is likely to reduce pressure on natural resources and environmental damage relative to growth solely driven by industrial production.

Editors’ note: A version of this column first appeared on VoxChina.

References

Beerli, A, F J Weiss, F Zilibotti, and J Zweimüller (2020), “Demand Forces of Technical Change Evidence from the Chinese Manufacturing Industry”, China Economic Review 60: 101157.

Chen, W, X Chen, C-T Hsieh, and Z M Song (2019), “A Forensic Examination of China's National Accounts”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Spring): 77–127.

Chen, X, G Pei, Z M Song, and F Zilibotti (2022), “Tertiarization Like China”, Annual Review of Economics 15 (forthcoming).

Duernecker, G, B Herrendorf, and Á Valentinyi (2017), “Structural Change within the Service Sector and the Future of Baumol’s Disease”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12467.

Duernecker, G, B Herrendorf, and Á Valentinyi (2018), “Structural Change and the Productivity Slowdown”, VoxEU.org, 16 May.

Fan, T, M Peters, and F Zilibotti (2022), “Growing Like India: The Unequal Effects of Service-Led Growth”, NBER Working Paper No. 28551.

Fang, L and B Herrendorf (2021), “High-Skilled Services and Development in China”, Journal of Development Economics 151 (June), 102671.

Guo, K, J Hang, and S Yan (2021), “Servicification of Investment and Structural Transformation: The Case of China”, China Economic Review 67 (June), 101621.

Liao, J. (2020), “The Rise of the Service Sector in China”, China Economic Review 59 (February), 101385.

Lu, M, X Xi, and Y Zhong (2022), “Urbanisation and the Rise of Services: Evidence from China”, Working Paper.

Song, Z, K Storesletten, and F Zilibotti (2011), “Growing Like China”, American Economic Review 60 (101): 196–233.