Should we conclude that tariff liberalisation aimed at furthering gains from trade has largely run its course, and compared to the past has much less of a role to play in the world today? It might look that way, with trade growth stagnant, little to show for a decade of WTO talks, and substantial roadblocks even standing in the way of smaller-scale deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

After six post-war decades of relentless progress, world trade growth and world trade liberalisation have both now seemingly ground to halt. Globally, trade grew twice as fast as GDP in the 25 years prior to 2007, but at a rate below GDP since late 2011. The many rounds of multilateral tariff negotiations under the WTO have stalled, possibly to the point of no return, and the 2001 Doha Round was hailed as a development round but concluded with a few face-saving proposals and failed in its primary goal of lowering tariffs for developing countries.

And yet some might argue that, with tariffs already low, there are hardly any gains from liberalisation left on the table to speak of, and hence the gloomy current scenario is neither a surprise nor a cause for concern.

Production linkages and entry revisited

Starting from a standard new trade model framework (Melitz 2003, Chaney 2008), in our new paper we argue that such a mood of indifference may be misguided (Caliendo et al. 2017). The logic that welfare is maximised by optimal tariffs that are zero, or perhaps even positive, derives from a special class of models. A more general model, well suited to actual modern economic production structures, leads to a different conclusion.

We model a multi-sector world with production linkages between sectors (Caliendo and Parro 2015). Here, tariff liberalisation will in general have nontrivial entry effects. With these more general model foundations, we find that firm entry decisions can have meaningful impacts on trade policy, trade flows, and welfare, in ways not captured hitherto in many current-generation trade models. It is easy to show this by illustration in a simplified two-sector model with just one linkage, one traded differentiated good, and one competitive non-traded good.

In such a world, the presence of monopolistic competition implies an entry distortion, and under a plausible range of parameters this leads to a first-order loss when a small positive tariff is imposed starting from zero. As a direct corollary, it follows that the optimal tariff is then negative.

Putting data to work

To convincingly make the case for this argument, empirically as well as theoretically, we first expand the data universe to build a tariff dataset that includes not just the usual sample of advanced (e.g. OECD) economies, but also a large subsample of emerging and developing economies, using newly collected data going back to the 1980s.

We then build upon the most up-to-date model of international trade with heterogeneous firms, but extend this model to incorporate tariffs and the kind of input-output structure (production linkages) that is realistic for modern economies.

The model is calibrated to match observed data for 15 sectors in each of 189 countries. We then use this quantitative model to implement four policy experiments.

We first quantify the effects of arguably the most successful GATT/WTO process, the observed change in most-favoured nation (MFN) tariffs from 1990–2010, which we refer to as Uruguay Round. We then evaluate the impact of all observed changes in MFN and preferential tariffs over the last 20 years, which we refer to as Uruguay Round + Preference. After that, we ask if there are any further potential gains in the world today from zeroing all tariffs, which we refer to as Free Trade. Finally, in a separate exercise, we also investigate whether, starting from a free trade position, the imposition of negative tariffs would be optimal for each country acting individually.

Uruguay matters

We find that the Uruguay Round had a profound impact. Almost all the gains from tariff elimination in the last two decades result from the MFN tariff cuts in the Uruguay Round. The effects from other tariff reductions – namely, preferential trade agreements (PTAs) – contributed virtually nothing to total world trade and welfare. In fact, we find that PTAs generated only a tiny average increase in the world trade share (measured as imports/GDP), whereas on its own the Uruguay Round doubled the average trade share. In terms of welfare, the Uruguay Round generated an average increase in world welfare of 1.43%, while the additional effect from PTAs was only 0.13%, an order of magnitude smaller.

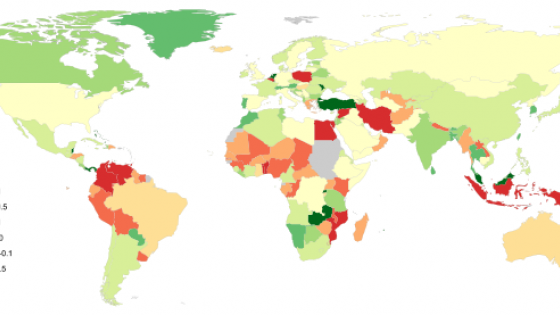

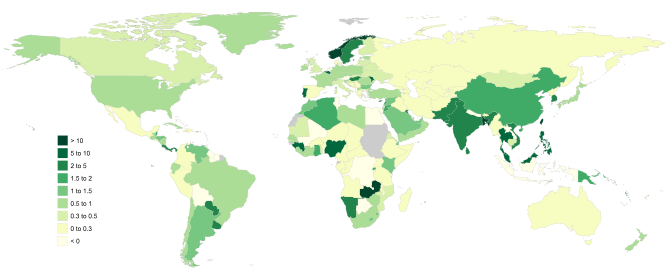

Figure 1 presents a map of the world showing the total gains from actual tariff changes moving from 1990 to 2010. Figure 2 shows gains from hypothetical tariff changes moving from 2010 to zero tariffs.

When looking at countries by income group, we find that both the advanced and the emerging and developing economies gained substantially from their own Uruguay Round tariff elimination, even if there were no tariff reductions by the other group. This is also a radical and unusual result, since it suggests that these country groups, at least when each is seen collectively, do not have an incentive to impose beggar-thy-neighbour positive optimal tariffs; rather, each side would mutually gain from either side liberalising – a win-win scenario. This result has important implications for international trade negotiations, as large groups of countries can benefit from MFN tariff reductions even if other countries do not participate.

Figure 1 Welfare gains from actual tariff changes moving from 1990 to 2010

Figure 2 Welfare gains from hypothetical tariff changes moving from 2010 to zero tariffs

More gains from trade than we thought

The results are striking when we consider the effects of moving to a free trade world with zero tariffs. Our results show that there are extra gains for about one third of the countries in the world, and these are mostly emerging and developing economies.

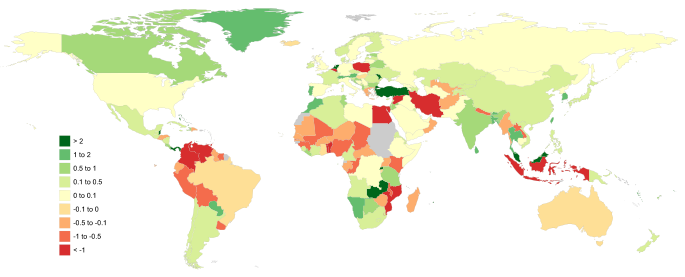

Yet, while some of these countries gain from the complete removal of tariffs, a smaller number of economies (about one-quarter of countries in the world) would gain from going even further, to negative (optimal) tariffs. These countries are mostly remote economies, but also include a smaller number of economies with very strong production linkages with the rest of the world.

Our theoretical results show that either of those two conditions – remoteness or strong production linkages – can lead to negative (optimal) tariffs. This policy would serve to facilitate trade into these countries and would raise welfare by more than the cost of providing the import subsidy, that is, even if consumers in these countries paid for the import subsidy, the policy would be welfare improving.

One component of ongoing trade negotiations is to enable trade facilitation through other, non-monetary means, such as decreasing the time spent at the border, red tape, and more. We expect that such policies would be strongly welfare-improving, not only through the usual channel of expanding trade and lowering prices, but also through encouraging the entry of exporters.

In sum, our research shows that when we take into account firm entry in a multi-sector, heterogeneous-firm trade model, we gain new insights into the potential welfare gains from trade liberalisation.

References

Chaney, T (2008), “Distorted Gravity: The Intensive and Extensive Margins of International Trade”, American Economic Review 98(4): 1707–21.

Caliendo, L, R C Feenstra, J Romalis and A M Taylor (2017), “Tariff Reductions, Entry, and Welfare: Theory and Evidence for the Last Two Decades”, CEPR Discussion Paper 10962 (revised version).

Caliendo, L and F Parro (2015), “Estimates of the Trade and Welfare Effects of NAFTA”, Review of Economic Studies 82 (1): 1–44.

Melitz, M J (2003), “The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity”, Econometrica 71(6):1695–1725.