President Trump’s announced intention to impose import tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium touched off a wave of retaliation threats and trade policy responses from trading partners, including the EU. Countries are reportedly already lining up their product lists of US exports over which to impose tariffs of their own. But what are we to make of these threats?

President Trump had kept under wraps the steel and aluminium products being investigated under Section 232 of the 1962 trade law that he is relying on to curb imports. Only after the investigation’s reports were finally made public on 16 February did it become clear that the tariffs – which his administration claims are necessary to protect national security – will cover $46 billion dollars of imports (US Department of Commerce 2018a,b). However, only 6% of those imports derive from the country the administration has labelled as the main culprit in flooding the world with steel and aluminium – China (Bown 2018).

Rules established by WTO dispute settlement permit a country to retaliate against an action such as the one Trump plans to take if there is a legal finding that the national security rationale is baseless. The compensation – or retaliation – limit has historically been set at the value of an exporting country’s lost trade.

However, it could take years for retaliation under the process of formal WTO dispute settlement to unfold. As a result, countries may take other steps to circumvent that process, while at the same time claiming that they are relying on basic WTO rules to guide their retaliation response.

Using information reported from the Trump administration’s own models, I estimate that Trump’s steel and aluminium tariffs would impose trade losses on partners equal to $14.2 billion per year, an amount establishing the collective permissible retaliation. The countries hit the hardest by Trump’s tariffs are Canada ($3.2 billion), the EU ($2.6 billion), South Korea ($1.1 billion), and Mexico ($1.0 billion).

Importantly, China would only suffer $689 million in estimated trade losses and thus only be authorised that much in retaliation. The US currently imports relatively less steel and aluminium from China because previously imposed antidumping and countervailing duties have already severely limited US imports from China of those products (Bown 2017a).

The WTO dispute settlement approach

Here is how the WTO would approach the issue. Given the completed investigations under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, assume that Trump proceeds with tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium. WTO member countries would then challenge his claim that the tariffs are justifiable under the GATT Article XXI “national security” exception. Further assume a WTO Panel and the Appellate Body reject Trump’s defence and find the tariffs inconsistent with US obligations.1 In that event, suppose the Trump administration nevertheless refuses to amend the tariffs. Complaining countries can then request compensation and the WTO can establish authorised retaliation.2 Cases like these are rare – the WTO has established the retaliation limit in fewer than 15 disputes since 1995, and in even fewer instances have countries implemented the retaliation.

WTO retaliation is not punitive. Under the principle of reciprocity, the WTO would limit the amount “equivalent to the level of nullification and impairment” that resulted from Trump’s policies. In practice, establishing the limit requires that WTO arbitrators follow a two-step process: (1) decide on a mathematical formula, and (2) decide on key parameter values so as to apply that formula to the context at hand.

In disputes involving WTO-inconsistent import restrictions – e.g. tariffs, quotas, and non-tariff measures that limit imports – arbitrators have settled on use of the ‘trade effects’ formula. Historically, the formula has been defined as the difference between imports under the WTO-inconsistent policy and a ‘counterfactual’ level of imports that would have arisen but for the policy. That is the formula applied here.

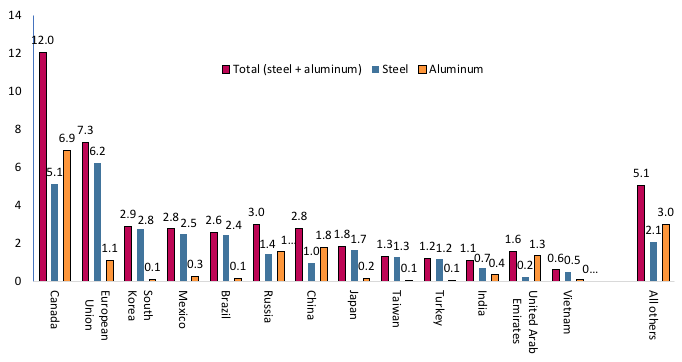

The second step involves deciding on the monetary values to be assessed. First, for the counterfactual values for trade flows in the absence of Trump’s tariffs, I use the 2017 levels of US imports of the investigated products and subject to the tariffs. Overall, these were $29 billion for steel and $17 billion for aluminium.3 Figure 1 illustrates the foreign source of 2017 US imports by product and by partner. Top foreign sources for both products combined include Canada ($12 billion), the EU ($7.3 billion), Russia ($3 billion), South Korea ($2.9 billion), and Mexico ($2.8 billion).

Notably, China exported only $976 million of steel and $1.8 billion of aluminium products to the US, or just 6% of the $46 billion of US steel and aluminium imports over which Trump is imposing tariffs.

Figure 1 US imports of steel and aluminium in 2017, be selected trading partner (billions of US dollars)

Note: Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Sources: Author’s calculations based on matching the Harmonized Tariff Schedule product codes in the two Section 232 reports (US Department of Commerce 2018a, b) to 2017 import values from the United States International Trade Commission Dataweb (aluminium) and Commerce Department’s Import Monitor (steel).

Second, I rely on the Commerce Department’s own estimates from the Section 232 reports (US Department of Commerce 2018a,b) to establish estimates of the levels of trade that would result from Trump’s tariffs. For steel, the report alludes to an economic model that claims a 24% tariff is equivalent to an import volume reduction of 37%. For aluminium, the claim is that a 7.7% tariff is equivalent to an import volume reduction of 13.3%. As I do not have access to their underlying models, I assume a linear relationship between each product’s tariff and its trade volume reduction. Under this assumption, Trump’s proposed 25% tariff on steel would lead to a 38.5% cut in steel imports, and a 10% tariff on aluminium would lead to a 17.3% cut in aluminium imports.4 I apply these cuts to bilateral US imports of steel and aluminium in 2017.

Who would be authorised to retaliate and by how much?

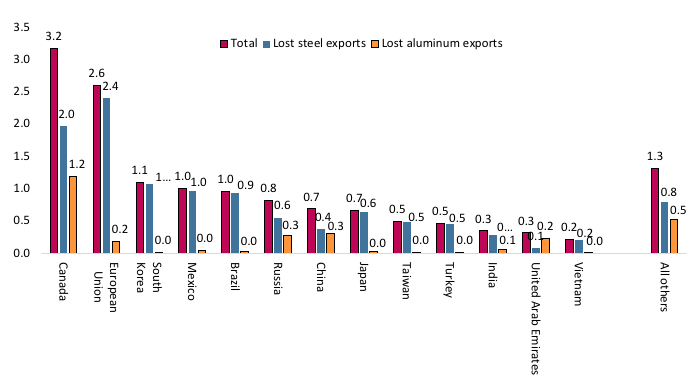

Figure 2 illustrates the total amount of each country’s retaliation, as well as whether the lost trade derives from lost steel or aluminium exports. Because Trump’s proposed tariffs would be applied to imports from all partners equally, trade losses will be largest for countries that are the largest sources of US imports of steel and aluminium.

Canada would be granted the largest retaliation at $3.2 billion (for $2 billion of lost steel exports and $1.2 billion of lost aluminium exports). The EU would be granted $2.6 billion ($2.4 billion for steel, $0.2 billion for aluminium), followed by South Korea ($1.1 billion), Mexico ($1 billion), Brazil ($965 million) and Russia ($823 million). Others with sizable losses include Japan, Taiwan, Turkey, India, the United Arab Emirates, and Vietnam.

Figure 2 Estimated lost exports and retaliation limits if Trump imposes tariffs (billions of US dollars)

Note: Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Author’s calculations as explained in the text under the assumption that President Trump imposes an import tariff of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium.

China would only be authorised to retaliate by $689 million ($376 million for lost steel exports and $313 for lost aluminium exports).

If the sources of all US steel and aluminium imports were part of this dispute, trading partners would be permitted to retaliate by a collective amount of $14.2 billion per year. The largest authorised WTO retaliation to date is the $4 billion that the EU was authorized to retaliate at the conclusion of the United States—Foreign Sales Corporation dispute in 2002. The second largest was the US—Country of Origin Labeling dispute in which Canada was authorised to retaliate by $1.1 billion in 2015.

How might countries implement the retaliation?

Countries frequently implement WTO retaliation by imposing 100% tariffs on a list of imported goods from the defendant that add up to less than the authorised limit. The logic is that the 100% tariff may be prohibitive; this would thus eliminate no more than that WTO-authorised limit.

The next decision for the retaliating country is to identify which products to put on its list. In the case against Trump, the EU has reportedly indicated its product list will include jeans, bourbon from Kentucky, cranberries and dairy products from Wisconsin, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, US steel products, and agricultural products like rice, maize, and orange juice (Donnan and Wigglesworth 2018).

The complaining country typically has discretion to determine which products to target. It may select products based on political motives – for example, inflicting economic costs on key Congressional leaders in the hope that they will effectively persuade Trump to implement policies that conform with international rules.

Finally, it is also worth noting that authorisation of retaliation arising from a WTO dispute can take many years to play out.6 For that reason, trading partners may also impose more immediate import restrictions – perhaps also guided by these ‘compensation’ (retaliation) limits set out here. They may argue that Trump’s original tariffs should be viewed not as a justified national security exception but as a safeguard, in which case partners can request a more immediate remedy, for example, if there was not an absolute surge in the imports being protected.7

Author’s note: I thank Junie Joseph for outstanding research assistance and Olivier Blanchard, Monica de Bolle, Mary Lovely, Jacob Kirkegaard, Ted Truman, and Steve Weisman for helpful discussions and comments.

References

Bown, C P (2017a), “Steel, Aluminum, Lumber, Solar: Trump's Stealth Trade Protection”, PIIE Policy Brief 17-21, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Bown, C P (2017b), “Will the Proposed US Border Tax Provoke WTO Retaliation from Trading Partners?”, PIIE Policy Brief 17-11, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Bown, C P (2018), "Trump has announced massive aluminum and steel tariffs. Here are 5 things you need to know," 1 March, Monkey Cage, Washington Post.

Bown, C P and R Brewster (2017), “US - COOL Retaliation: The WTO's Article 22.6 Arbitration”, World Trade Review 16(2): 371-394.

Bown, C P and M Ruta (2010), “The Economics of Permissible WTO Retaliation”, in C P Bown and J Pauwelyn (eds), The Law, Economics and Politics of Retaliation in WTO Dispute Settlement, Cambridge University Press: 149-193.

Donnan, S and R Wigglesworth (2018), “Trump fires back at EU tariff retaliation threats” 3 March, Financial Times.

Horn, H, L Johannesson, and P C Mavroidis (2011), “The WTO Dispute Settlement System 1995–2010: Some Descriptive Statistics”, Journal of World Trade 45(6): 1107–138.

US Department of Commerce (2018a), “The Effect of Imports of Steel on the National Security: An Investigation Conducted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as Amended”, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Office of Technology Evaluation, 11 January.

US Department of Commerce (2018b), “The Effect of Imports of Aluminum on the National Security: An Investigation Conducted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as Amended”, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Office of Technology Evaluation, 17 January.

Yoo, J Y and D Ahn (2016), “Security Exceptions in the WTO System: Bridge or Bottle-Neck for Trade and Security?”, Journal of International Economic Law 19(2): 417–44.

Endnotes

1. For a discussion of GATT Article XXI see Yoo and Ahn (2016). In this column I will not comment on the legal question of the WTO-consistency of Trump imposing tariffs under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. I assume they are WTO-inconsistent for the purpose of establishing one aspect of the potential costs – in the form of authorisable trading partner retaliation against US exports - of such tariffs.

2. This is discussed more formally in Bown and Ruta (2010) for disputes prior to 2008, in Bown and Brewster (2017) for the US – Country of Origin Labeling dispute involving Canada and Mexico, and in Bown (2017b) in light of a potential dispute involving the proposed border adjustment tax.

3. Computed as described in the note under Figure 1. These data were not included in the Section 232 reports but had to be constructed independently based on information provided therein.

4. This implicitly assumes that the exporter-received price for steel and aluminum will not fall because of the tariffs, a dubious assumption given the size of the United States as an importer and its likely market power. As discussed in Bown and Brewster (2017, 382) what results is retaliation limits that should be treated as the lower bound. If exporter-received prices fall considerably because of the tariffs, authorized retaliation could be even larger.

5. Horn, Johannesson, and Mavroidis (2011, table 22) show the average length of time that disputes taking place spent at each phase of the WTO’s full dispute resolution process between 1995 and 2010.

7. This may be what is motivating the EU’s potential response reported in Shawn Donnan and Wigglesworth (2018).