On 8 March 2018, President Trump invoked the Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act to impose, on national security grounds, 25% and 10% tariffs on steel and aluminium imports, respectively (Hillman and Tippett 2021). Subsequently, on 31 October 2021, under the auspices of Trump’s successor, the US agreed on suspend these tariffs on steel and aluminium imported from the EU. During this suspension, the EU and US were supposed to negotiate a bilateral arrangement to address carbon emissions on steel and aluminium production while restoring “market-oriented conditions”, trade diplomat speak for reducing overcapacity on world markets.

Negotiating the GSA

The original deadline to achieve this agreement – the Global Arrangement on Sustainable Steel and Aluminium (GSA) – was 31 October 2023. Yet, according to the negotiators and leaked press, an agreement before the end of this year is unlikely. Several factors are said to contribute to this deadlock:

- The design proposed by the US for the GSA club contains multiple goals. Some contest (e.g. Falkner et al. 2022) that such issue-linkage runs into domestic political constraints and is not helping to conclude the negotiations.

- Another cause of friction is said to be inconsistencies between the US proposal and WTO law as well as incompatibility with the recently adopted EU CBAM (Kleimann 2023).

- The EU appears to advocate building on the US proposal so as to expand the agreement to include other like-minded countries to join this sectoral ‘climate club’. One goal is to use this club as a tool to discourage the use of export curbs on raw materials and related products.

Lessons from a decade of trade data on imported steel and aluminium

As GSA-related negotiations intensify, it is worth asking: how much trade is at stake and what leverage the transatlantic trading powers have left over China in sectors already subject to supplementary tariffs? We examined these matters based on steel and aluminium trade flow data from 2013 to 2023Q2.

Four findings are germane to the ongoing GSA negotiations.

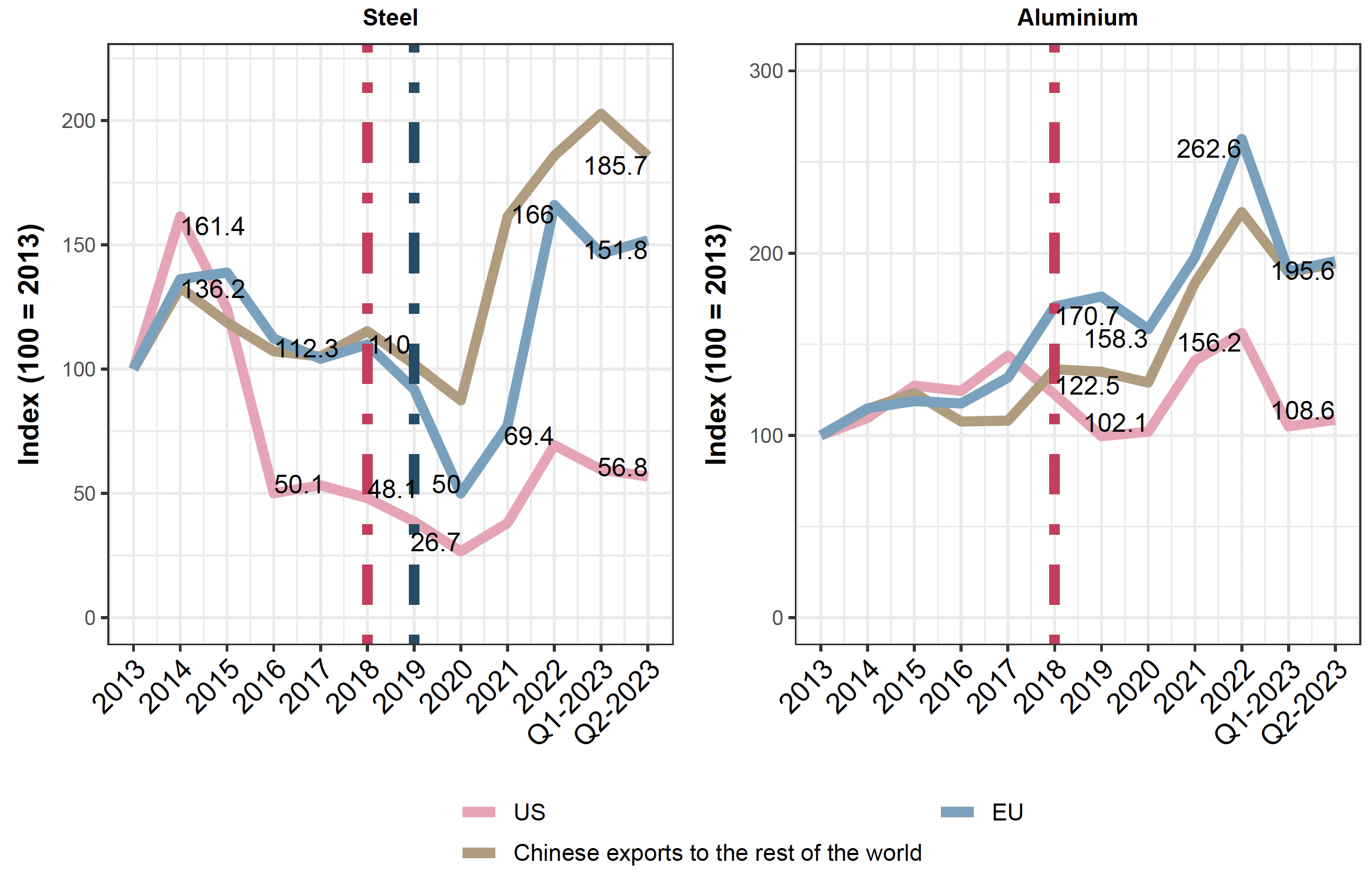

Firstly, what is the importance of steel and aluminium exports from China in the US and EU market? While 2021 and 2022 witnessed sharp increases in Chinese exports of steel and aluminium to EU and US markets (see Figure 1), such exports may well be in retreat given a fall in the first half of 2023 and the recently reported pickup in the Chinese economy in Q3 2023. Higher Chinese GDP growth is said to bolster domestic demand for these goods, leaving less available to export.

Second, what was the impact of the 2018 Trump’s tariffs and the 2019 EU anti-subsidy investigation? While the EU and the US increased their sourcing of Chinese aluminium steadily from 2013, imports of Chinese steel in both markets started falling before the imposition of Trump’s tariffs in 2018 and the conclusion of an anti-subsidy investigation by the EU in 2019. Since then, the percentage drop was larger for the EU market compared to the US.

Evidently, these tariffs on Chinese steel did not stop the surge in Chinese exports in 2021 and 2022, raising the question whether additional GSA-related EU tariffs would be equally ineffective. As the right hand panel of Figure 1 shows, the imposition of US tariffs on aluminium imports in 2018 coincided with Chinese shipments being deflected to the EU market. Moreover, US tariffs did not prevent the recent jump in Chinese aluminium imports.

Figure 1 Steel and aluminium imports from China surge in 2021 and 2022 then retreat

Note: *2023 data annualised.

Source: Trade Data Monitor, LLC.

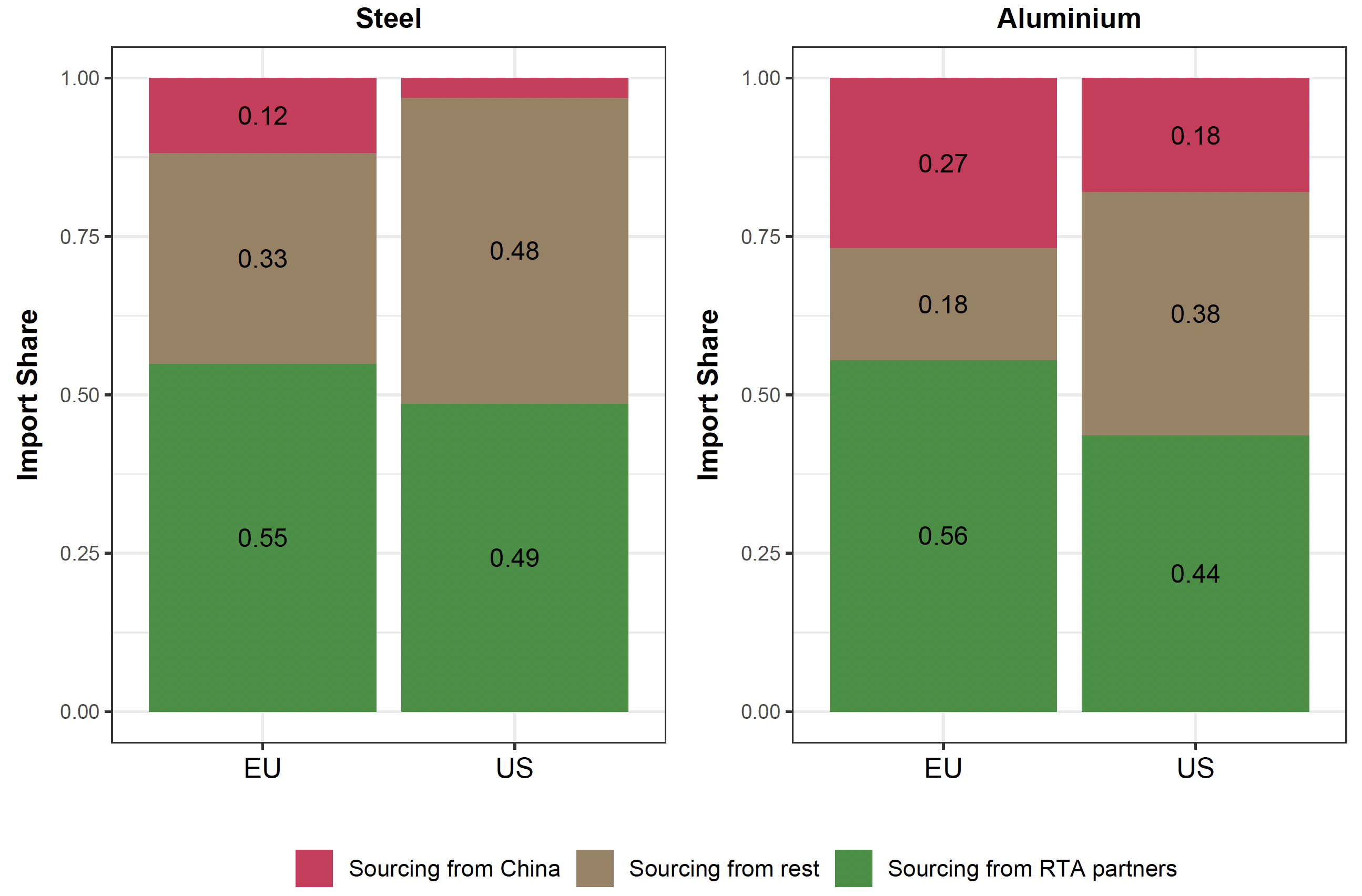

Third, assuming any GSA tariffs do not explicitly target China, what other trading partners of the EU and US would be affected? Both the US and EU source plenty of steel from regional trade agreement (RTA) partners (see Figure 2). It is unlikely the relevant regional trade agreements contain provisions allowing for supplementary tariffs on the grounds of carbon content. Recall in this regard, Canada and Mexico were originally exempted from the US tariffs imposed in 2018. How any GSA treats imports from RTA partners will be critical, especially for the EU which has a large network of RTAs.

Figure 2 In 2022 the EU and US sourced lots of steel and aluminium from RTA partners

Source: Trade Data Monitor, LLC.

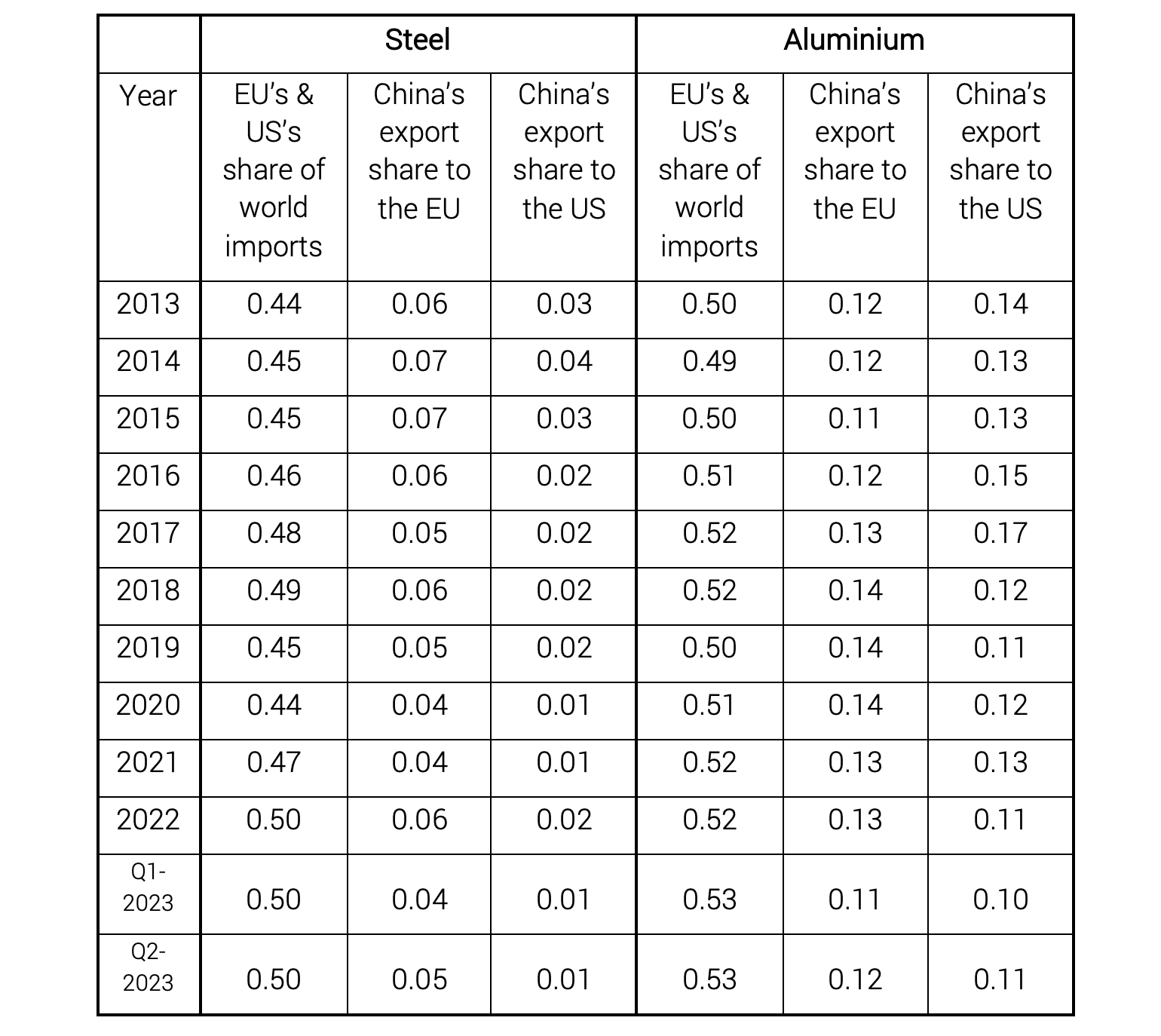

Fourth, what would be the leverage of the GSA given the sourcing patterns of steel and aluminium by the US and the EU? Together, the EU and US purchase half of global cross-border supplies of aluminium and steel (see Table 1). However, due in part to previous tariff actions, the percentage of Chinese exports currently going to these transatlantic trading giants is less than 7% in steel and below 24% in aluminium.

Such limited EU and US leverage is unlikely to change investment plans of Chinese steel producers. Moreover, limited transatlantic heft probably accounts for the talk of expanding the GSA to other like-minded countries. Higher tariffs on Chinese steel and aluminium exports to EU and US will likely result in redirection of exports to third markets – and this may not be without cost to Chinese firms that may have to accept lower export prices, etc.

Table 1 Share of world imports have maintained steady since 2013 with a higher importance of aluminium for the EU and the US combined

Note: *Export share = Chinese exports of steel or aluminium to the EU or the US/Total Chinese exports of steel or aluminium.

Source: Trade Data Monitor LLC.

Prognosis

While the GSA has yet to be finalised and only some preliminary details have made public or leaked, recent trade data on steel and aluminium points to modest transatlantic leverage over Chinese suppliers to these markets, especially in steel. If the primary objective of the GSA is to incentivising low-carbon production in the steel and aluminium Chinese industries, the outcome is likely to be disappointing. Based on trade flows data it is difficult to see how GSA-related incentives for Chinese decarbonisation could be decisive.

References

Falkner, R, N Nasiritousi and G Reischl (2022), “‘Climate clubs: politically feasible and desirable? “, Climate Policy 22(4): 480-487.

Hillman, J and A Tippett (2021), “A New Transatlantic Agreement Could Hold the Key to Green Steel and Aluminium”, Council on Foreign Relations Blog, 19 November.

Kleimann, D (2023), “Section 232 Reloaded: The False Promise of the Transatlantic ‘Climate Club’ for Steel and Aluminium”, Policy Contribution 11/2023, Bruegel.