Editors' note: This column is part of the Vox debate on the economic consequences of war.

Population dynamics, and more specifically human capital formation, are the determining factor for economic growth (Angrist et al. 2021). Before the Industrial Revolution, economic growth was practically aligned to population growth (Murphy et al. 2008). Later, from 1913 to 2010, average annual population growth amounted to 1.4% worldwide, while real GDP growth stood at 3% (Peterson 2017). This implies that population change still amounted to almost half of total economic growth, notwithstanding the dramatic technological advances and productivity changes that the world saw in the 20th century (Evenett and Baldwin 2021).

Population growth matters even more when capital is destroyed due to war. Germany had a skilled workforce prior to WWII, but its capital and human stock were largely destroyed. However, Germany received more than 12 million refugees from former German territories east of the Oder and from areas with substantial German ethnic populations in central and eastern Europe. This influx of people contributed to the economic growth expansion in the succeeding decades (Hazlett 1978).

The cost of war is sometimes masked by national income accounting, which ignores the loss of lives and the destruction of physical and human capital associated with war (Broadberry and Harrison 2018).

Ukraine’s demographic trend before the war

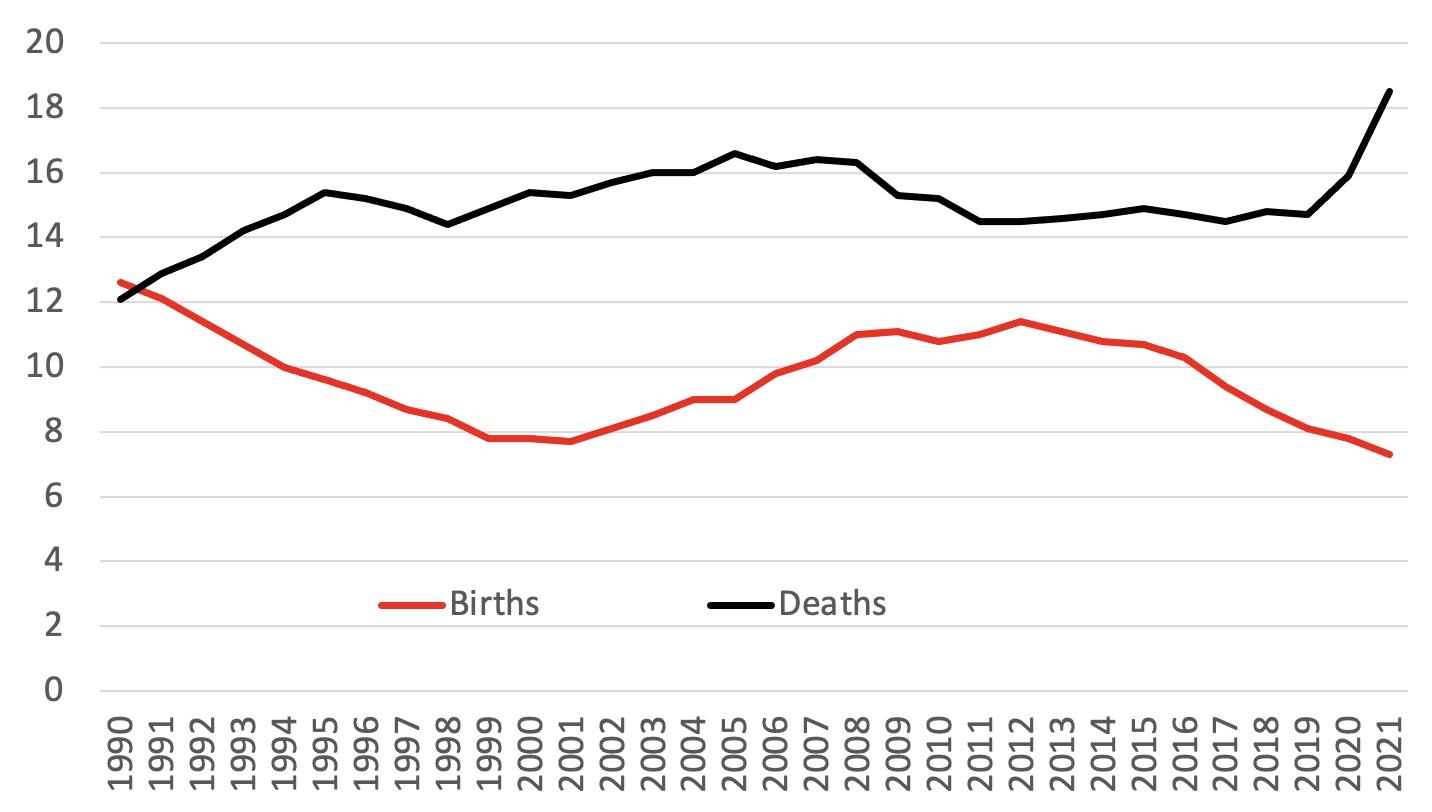

In the spring of 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic erupted, there was speculation that Ukraine would see a baby boom at the end of the year as home-locked families spent more time together. Instead, in the period December 2020 to February 2021 there were 5,000 fewer births than in the comparable period a year earlier. Covid-19 also had a sharp, upward effect on the death rate (Figure 1).

The pandemic only added to a pronounced downward demographic trend. A decade earlier, in 2012, Ukraine’s annual population decrease (without migration) was estimated at 142,400 people. By 2020, this decrease grew to 323,400 people and expanded to 442,300 people in 2021 (State Statistics Service 2022). This means that the country lost over 1% of its citizens the year before Russia’s invasion.

Figure 1 Birth and death rates in Ukraine (per 100,000 inhabitants)

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine, accessed 17 June 2022.

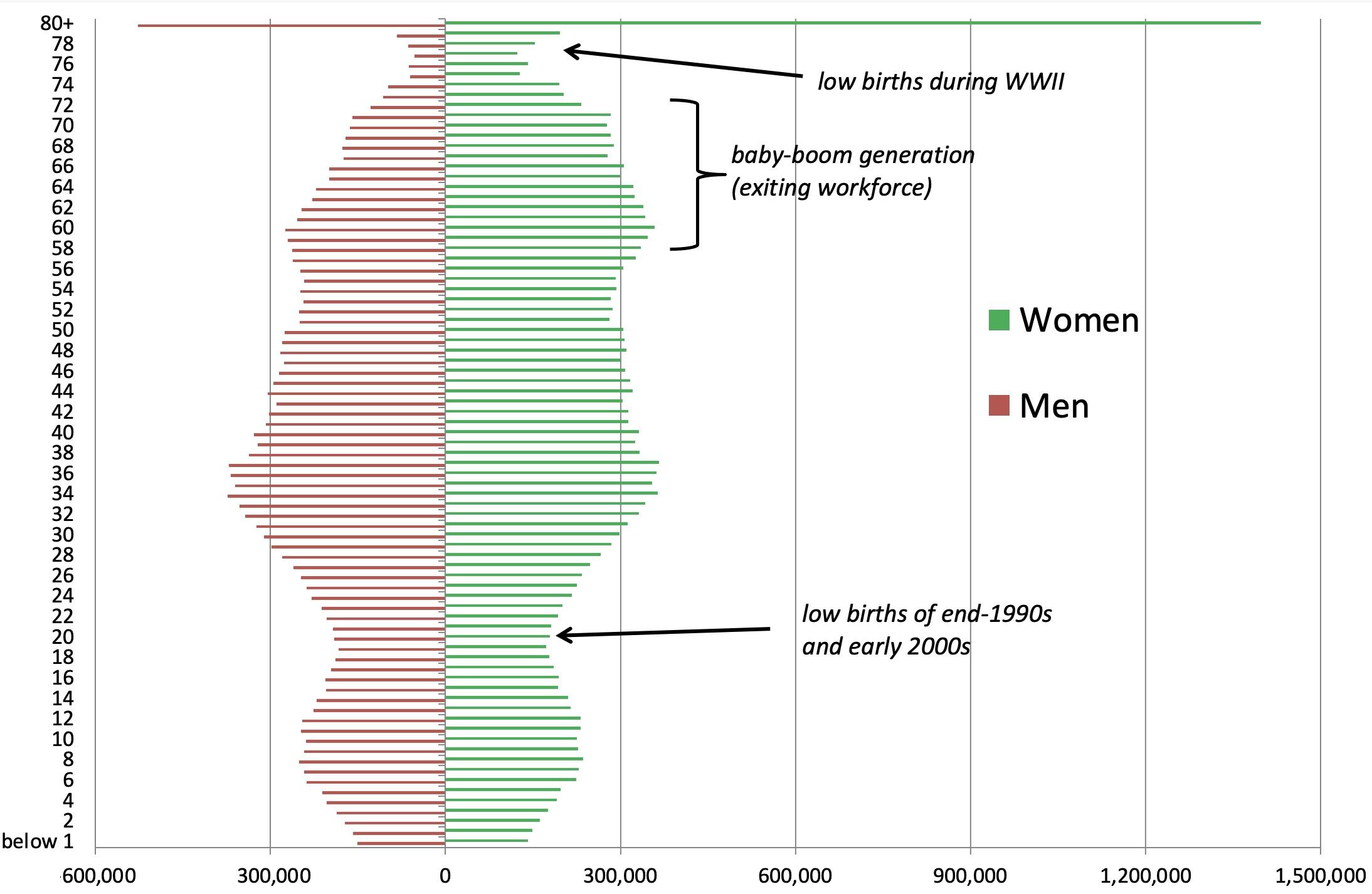

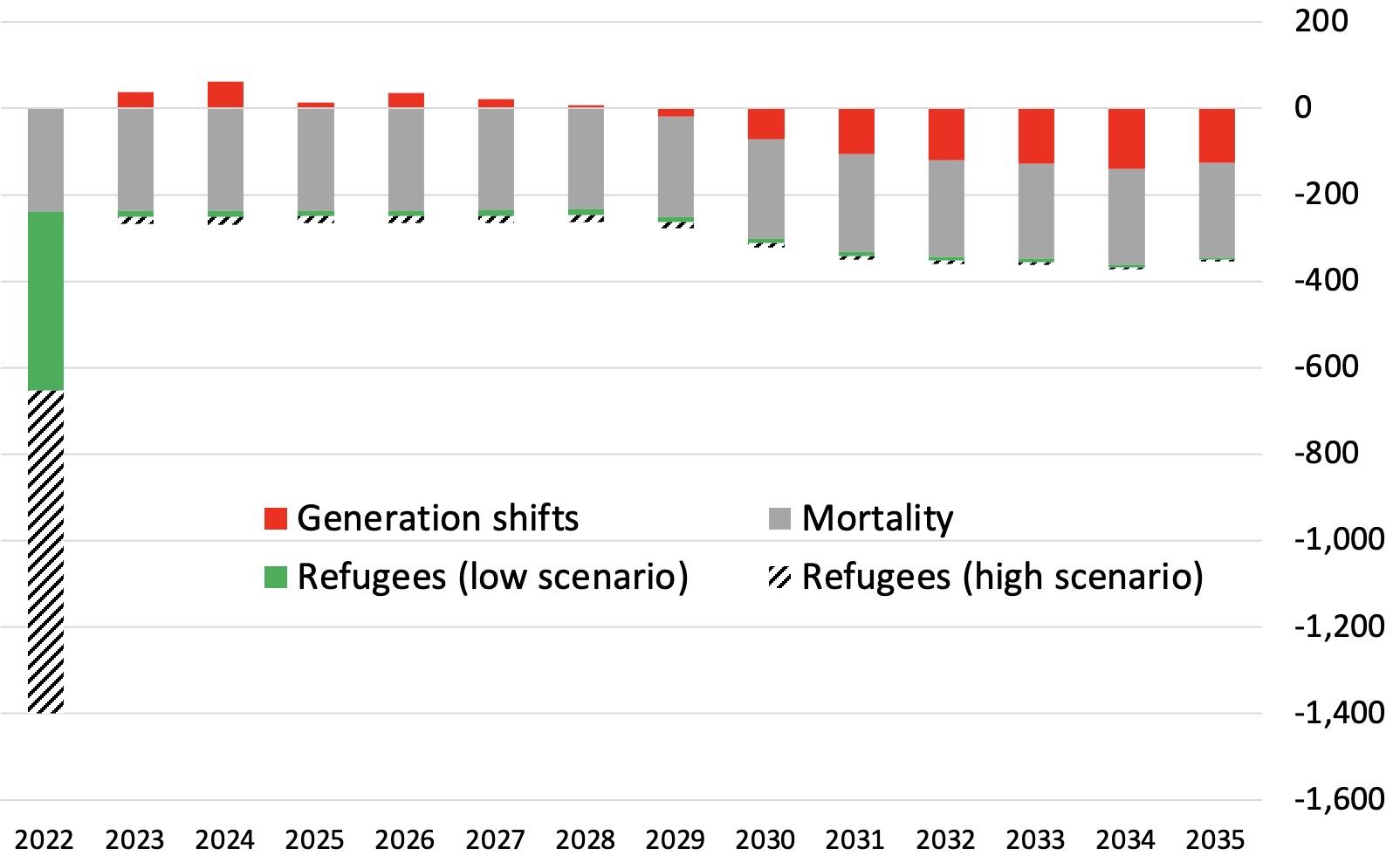

Ukraine’s population has been ageing fast: in 1990, its median age was 35; by 2010, it surpassed 39; and in 2022, at the start of the war, it was 41 years. The baby-boomer generation born after WWII has joined the ranks of pensioners (Figure 2). This generational shift means that Ukraine cannot replace its retiring workers with younger ones. Overall, by 2030, the total demographic toll on the economy (mortality and generation shifts combined) would increase to over 300,000 people exiting the workforce a year (Figure 3). And that was the trend before the war started.

Figure 2 Age-sex population structure in Ukraine as of 2021

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine, accessed 17 June 2022.

War and refugee crisis in 2022

Wars bring about deep demographic crises. During WWI, the fertility rates of European nations collapsed (Vandenbroucke 2012). In support of this finding, Caldwell (2004) shows that fertility declined in 13 other episodes of crises such as wars and revolution in various countries and periods of time.

The evidence suggests that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will further deepen the population decline. Already, a third of Ukraine’s population is on the move. Some 7.6 million Ukrainians have left the country and 5.1 million are still residing in other countries as of mid-June 2022 (UNHCR 2022). The latter is equivalent to 12–15% of the country’s population.

In the short term, this refugee wave lowers consumption and tax revenues in Ukraine. Ukrainians in Europe act as millions of individual importers, generating a daily foreign exchange drain of $100 million (National Bank of Ukraine 2022). Analysis of transactions in one of Ukraine’s leading banks suggests that the share of overseas payments with its debit and credit cards increased from 8% pre-war to 28% in May 2022 (Alfa-Bank 2022).

Nearly all adult Ukrainian refugees are women. Every third Ukrainian child is abroad. These families are temporarily separated from about 2 million men either waiting for them to return to Ukraine or considering joining them abroad after the war. Some of these refugees are likely to become long-term emigrants, especially as the war drags on and they find employment in other European countries. Even if only 15% of refugees and their family remain abroad once the war ends, this conservative estimate implies a strong one-off extra cut of around 400,000 to the rapidly dwindling workforce in Ukraine (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Annual change in Ukraine’s population aged 15-70

Source: authors’ estimates

Policies to ameliorate the population challenge

First, government policies should focus on creating incentives for Ukrainians abroad to return to Ukraine once the war is over. These policies may include monetary rewards to rebuilding homes and businesses. There should also be an international effort to bring back those over 1 million Ukrainians who were forcefully displaced into Russia since the start of hostilities.

Second, the government, with grants from the international community, should help those refugees who have lost family. These individuals should be provided with priority support in the form of welfare payments.

Third, child support policies can be aimed at increasing fertility rates. Policies can specifically lower the cost to women of childcare. A common mode of childcare is provided by day-care centres and preschools, which can be public or private. If such childcare is widely available, covers the working day, and is affordable, women with children have an easier time returning to work and might be more likely to have larger families as a result (Doepke et al. 2022).

Finally, the post-war recovery should be geared towards the creation of a new, green economy (Weder di Mauro 2021). The ongoing crisis presents a chance to reinvent Ukrainian economy, away from dependence on imported energy and towards the production of higher-value products. Investment in education is the core of this growth strategy.

References

Alfa-Bank (2022), “Ukrainians Abroad: How Much Do They Spend, Where and What they Buy”, Alfa-Bank.

Angrist, N, S Djankov, P Goldberg and H Patrinos (2022), “The loss of human capital in Ukraine”, VoxEU.org, 27 April.

Broadberry, S and M Harrison (2018), “New eBook: The economics of the Great War: A centennial perspective”, VoxEU.org, 6 November.

Caldwell, J (2004), “Social Upheaval and Fertility Decline”, Journal of Family History 29(4): 382-406.

Doepke, M and F Kindermann (2016), “Why European women are saying no to having (more) babies”, VoxEU.org, 3 May.

Doepke, M, A Hannusch, F Kindermann and M Tertilt (2022), “A new era in the economics of fertility,” VoxEU.org, 11 June.

Evenett, S and R Baldwin (2021), “Memo to the new WTO Director-General: Never waste a crisis”, VoxEU.org, 10 February.

Hazlett, T (1978), “The German Non-Miracle”, Reason 9(3): 33–37.

Murphy, K M, C Simon and R Tamura (2008), “Fertility decline, baby boom, and economic growth”, Journal of Human Capital 2(3): 262-302.

National Bank of Ukraine (2022), “Daily Outflow via Ukrainian-Issued Cards Abroad around $100 mln".

Peterson, E (2017), “The Role of Population in Economic Growth”, Sage Open 7(4).

State Statistics Service of Ukraine (2022), “Population (1990-2021)”.

UNHCR (2022), Operational Data Portal, Ukraine Refugee Situation.

Vandenbroucke, G (2012), “On a demographic consequence of the First World War,” VoxEU.org, 21 August.

Weder di Mauro, B (ed) (2021), Combatting Climate Change: A CEPR Collection, CEPR Press.