Fields of study (economics, physics, psychology, etc.) have become more specialised over time (e.g. Ramaley 1930, Ziman 1987, Wray 2005). While specialisation is thought to result in deeper and more precise knowledge, it has also created barriers to communication and collaboration across different fields of study (e.g. Becker and Murphy 1992, Walsh and Maloney 2007, Anderson and Richards-Shubik 2022). Within fields, a common division exists between a theoretical and an experimental/applied branch. Ideally, a feedback loop should exist between these two branches, with the theoretical one providing new theories to be tested, and the empirical one providing novel data useful in the development, rejection, or validation of these theories (Putnam 1979, Reeves et al. 2008). This division has been documented in several fields of study, including physics, psychology, and biology.

Economics is no exception, and a division between theoretical and applied economics is believed to exist (e.g. Backhouse and Cherrier 2014, Hamermesh 2018, Angrist et al. 2017). Specialised journals exist for both theory and applied economics, applied/theory oriented postgraduate programmes exist, and some universities even have dedicated applied economics departments. What is less clear is how these two branches interact with each other. Do they feed back to each other? Or, as it is believed to be the case across fields of study, they are becoming so specialised that collaboration/interaction is being precluded? Focusing on what we refer to as ‘fields of economics research’ (applied, applied theory, econometric methods, and theory), in a recent paper (Galiani et al. 2023) we empirically address this issue by analysing long-term trends in the contents of, and the citations received and generated by, a large and representative corpus of economics research articles. We associate specialisation with patterns that reveal a discipline is narrowing the topics it covers, as well as patterns suggesting the field is receiving fewer citation from outside fields.

Data

We first collected data from: (1) Constellate, a text analytics service provided by ITHAKA, the not-for-profit organisation managing both JSTOR and Portico; (2) Semantic Scholar, an artificial intelligence-powered research tool for scientific literature developed by the Allen Institute for AI (Kinney et al. 2023); and (3) Anauati et al. (2016, 2020), two papers in which field of economics research tags were manually assigned to a sample of economics research articles. Then, we built a comprehensive corpus of 24,273 economics research articles published in reputable general research economics journals during the period 1970-2016. The chosen journals include the ‘Top Five’ general research economics journals. To enhance the collected data, we utilised a combination of traditional and advanced natural language processing techniques. These techniques involved methods such as bag-of-words representations with multinomial regularised logistic regressions, latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) models, and text classification utilising BERT-like models (Beltagy et al. 2019). For each article in our corpus, we identified the following:

- Field of economics research. We associate a field of economics research with the methodological strategies used to address a research question. Applied papers are papers that have an empirical or applied motivation. They rely on the use of econometric or statistical studies as a basis for analysing empirical data. Applied theory papers develop theoretical models to explain a fact. The empirical analysis is not the most important feature of the paper, but a supplement. Econometric methods papers are articles that develop econometric or statistical methodologies. Theory papers do not contain an empirical fact section.

- Citation and reference data. We collected comprehensive information on both the articles referenced by and citing each paper in our main sample. This data includes the field(s) of study associated with the referenced or citing articles (e.g. medicine, mathematics, etc.). Furthermore, for economics-related articles, we identified their specific field of economics research.

- Topics addressed. We employed an LDA generative model to detect the topics addressed within each article in our sample. LDA automatically identifies word groups that frequently co-occur in documents and assigns them to respective topics (see Blei et al. 2003, Hu 2009).

Results

Aggregate trends across fields of economics research

Figure 1 presents the annual distribution of articles across different fields of economics research published in the analysed outlets from 1970 up to and including 2016.

Figure 1 Trends in the yearly share of articles published by field of economics research

Notes: Trends are smoothed by fitting a generative additive model (GAM) to the data. See Hastie et al. (2009).

A notable shift in the publication landscape of general research journals in economics is observed, revealing a substantial reduction in the share of theory articles, accompanied by a sharp increase in applied and applied theory articles. This finding is in line with previous studies by Hamermesh (2013, 2018), Panhans and Singleton (2017), Backhouse and Cherrier (2014), and Angrist et al. (2017, 2020).

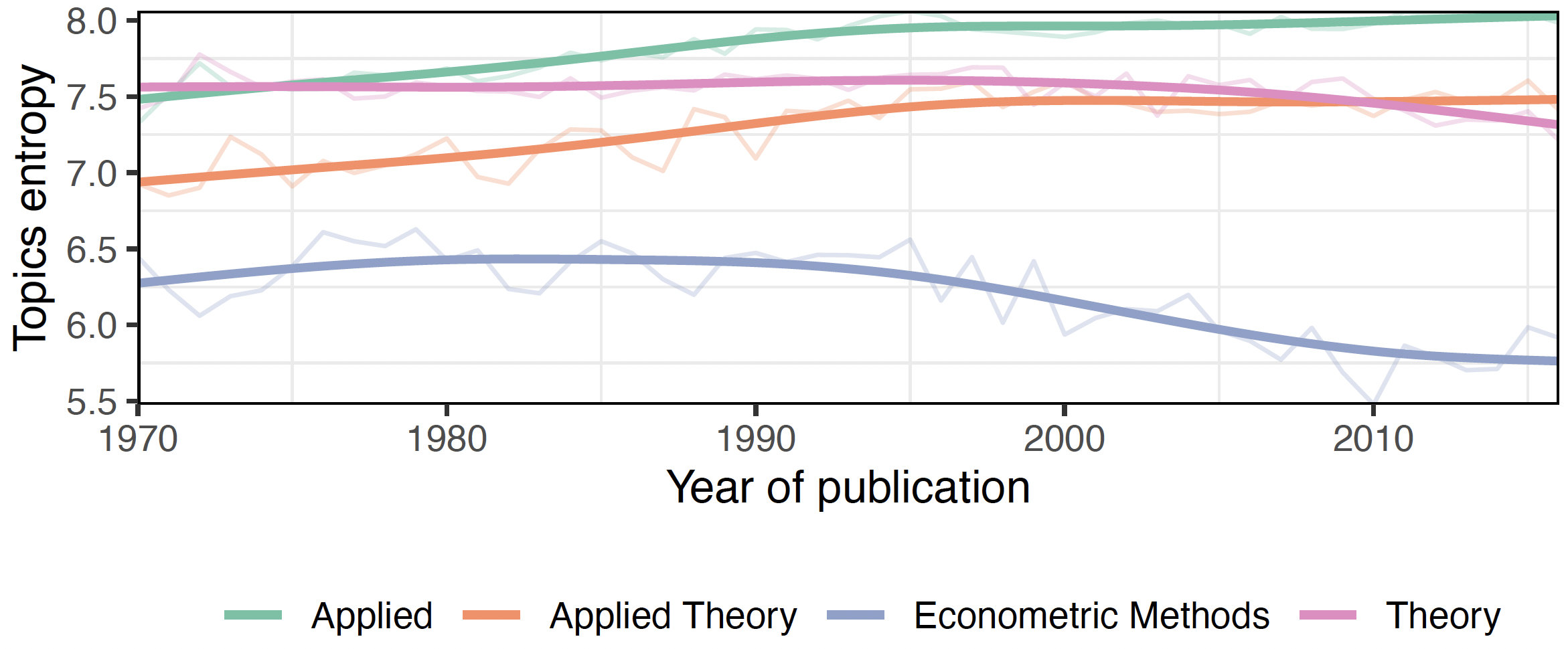

Figure 2 depicts the shifts in topic diversity across fields of economic research by analysing trends in topic entropy. For more details, please refer to Jurafsky and Martin (2009) and Galiani et al. (2023). Higher entropy values indicate that articles from a particular field and year cover a wider range of topics, while lower values suggest a narrower focus.

Figure 2 Topic entropy across fields of economics research

Notes: Trends are smoothed by fitting a generative additive model (GAM) to the data. See Hastie et al. (2009).

Trends in topic entropy differ across fields. Applied and applied theory articles demonstrated consistent positive trends. For theory articles it has remained relatively stable until the mid-1990s, after which a slight decline is observed. Econometric methods articles experienced a modest increase in topic entropy until the early 1990s, followed by a consistent decrease (reaching its lowest point by 2016).

The interplay between fields of economics research and fields of study other than economics

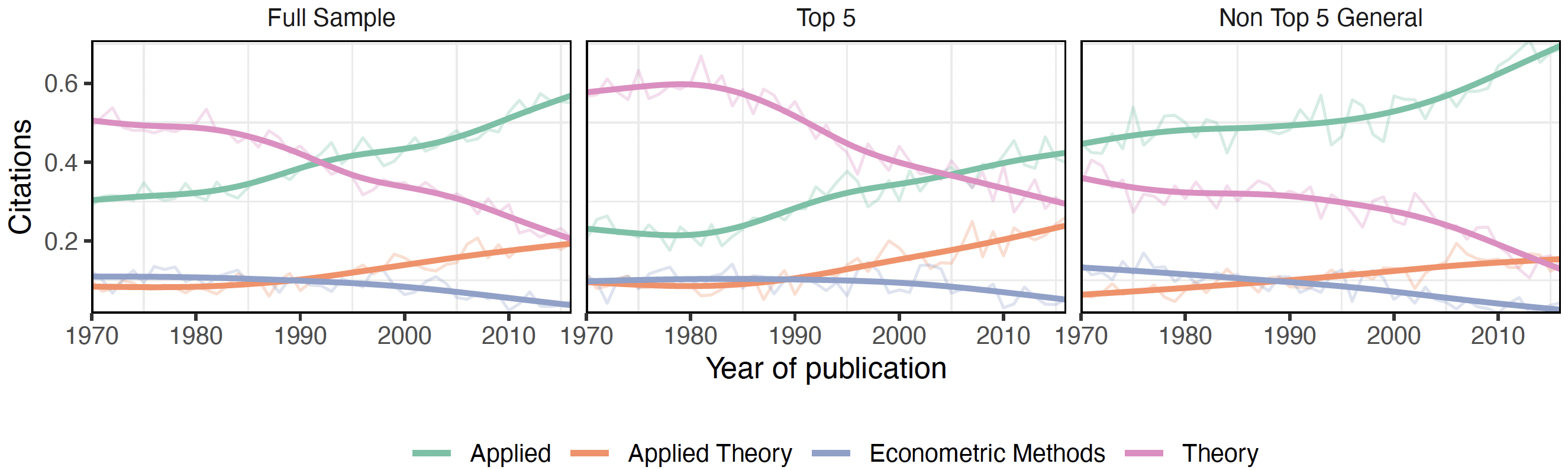

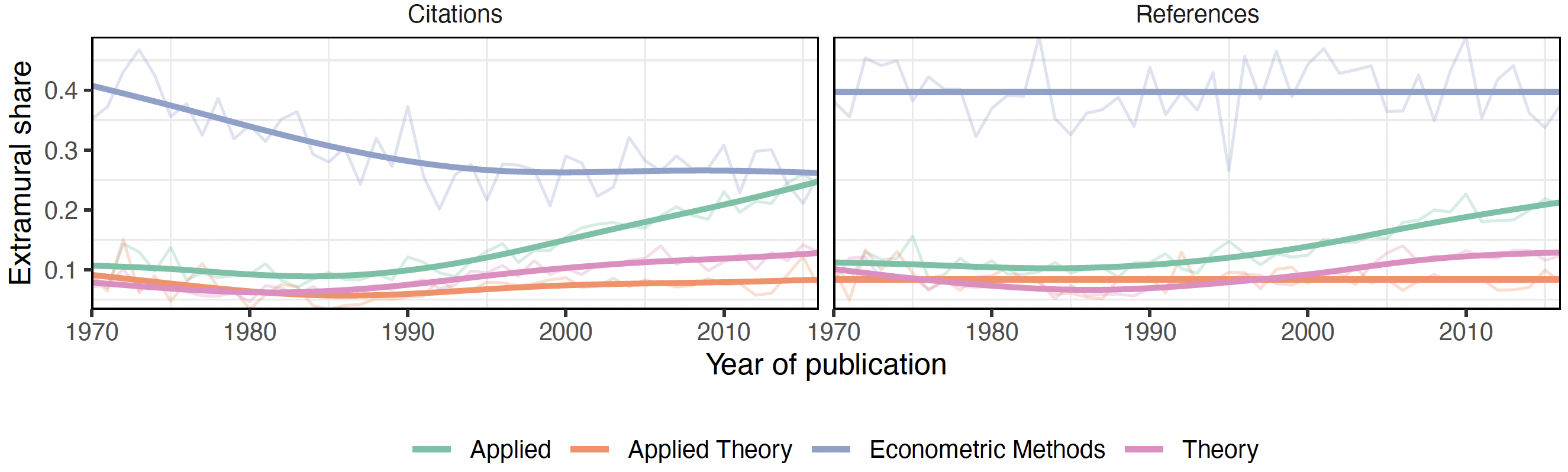

The leftmost panel of Figure 3 illustrates trends in the proportion of extramural citations received by the average article within each field of economics research. The rightmost panel shows trends in the proportion of extramural references (citations to articles from other fields generated by articles in our sample). This analysis is closely related to Angrist et al. (2020).

Figure 3 Share of extramural citations and references across fields of economics research

Notes: Trends are smoothed by fitting a generative additive model (GAM) to the data. See Hastie et al. (2009). We only consider citations received within the first seven years of publication.

Econometric methods papers receive a higher share of extramural citations and reference more extramural articles than any other field. Applied is the field that comes second in terms of extramural citations and references. For applied papers, we observe a steady increase in both extramural citations and extramural references since the early 1990s. By 2016, approximately 25% of all citations received by applied papers were from outside economics, and nearly 20% of their references were extramural ones. Both theory and applied theory papers displayed a more stable behaviour during the period 1970-2016.

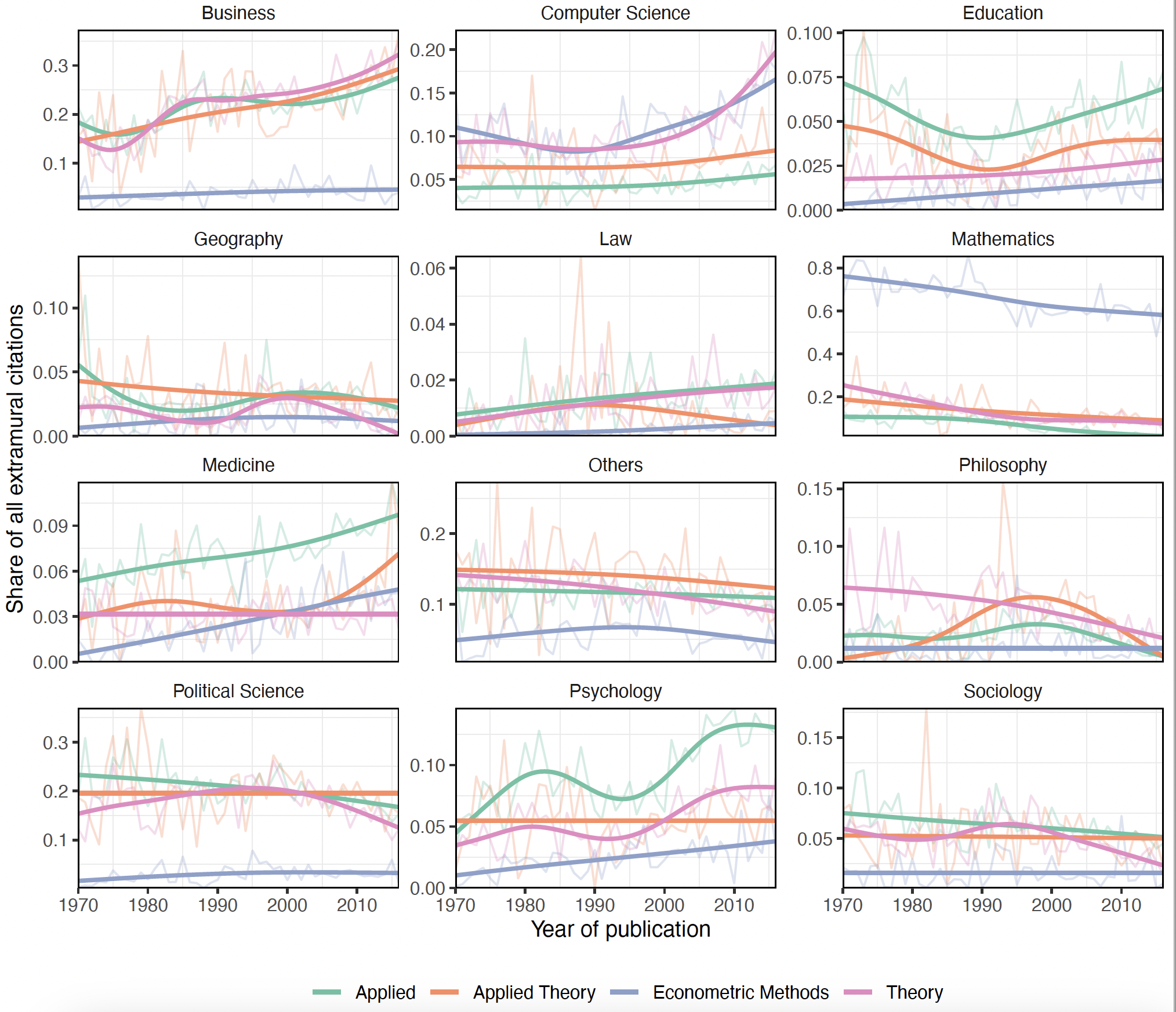

Figure 4 visualises how different fields of study interact with various fields of economics research.

Figure 4 Share of extramural citations received from non-economics fields by year of publication and field of economics research

Notes: Trends are smoothed by fitting a generative additive model (GAM) to the data. See Hastie et al. (2009). ‘Other’ includes: Agricultural and food sciences, art, biology, chemistry, engineering, environmental science, geology, history, linguistics, materials science, and physics. We only consider citations received within the first seven years of publication.

Trends in the origin of citations vary greatly across fields of economics research. For instance, there has been a significant increase in the number of citations from the field of medicine for applied papers. This trend is not observed in theory articles. By 2016, approximately 10% of all extramural citations for applied papers were sourced from medicine. Conversely, theory articles demonstrate a marked upward trend in citations from computer science. This pattern is also seen in econometric methods articles, but not in applied articles. Additionally, some fields of study seem to have lost importance in terms of citations to economics papers. This is the case for political science, philosophy, geography, sociology, and the disciplines included in ‘Others’ (when taken as a whole).

The interplay within and between fields of economics research

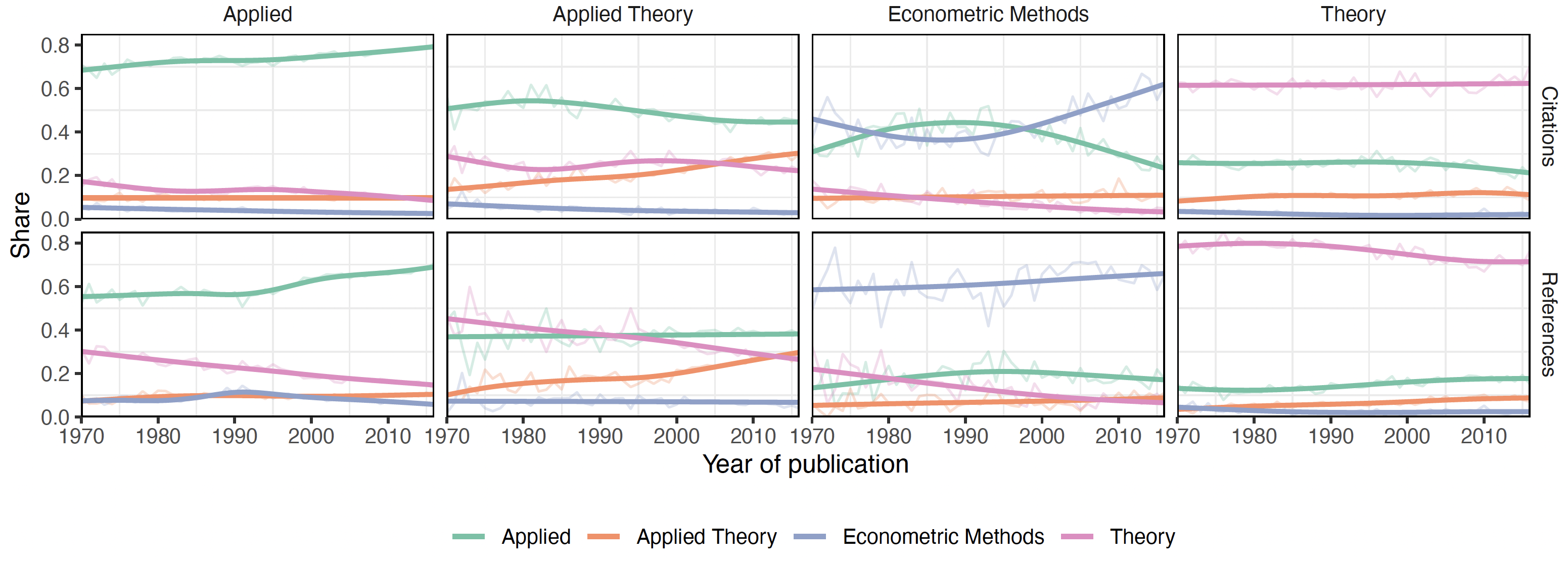

The upper panels of Figure 5 plot, for all fields of economics research, the share of citations (from economics articles) that come from a given field of economics research. The lower panels show, for all fields of economics research, the proportion of their references that cite articles of a given field of economics research.

Figure 5 Citations and references within and between fields of economics research

Notes: Trends are smoothed by fitting a generative additive model (GAM) to the data. See Hastie et al. (2009). We only consider citations received within the first seven years of publication.

A clear tendency towards homophily in the citation behaviour within different fields of economics research is observed. Homophily indicates that articles within a specific field of economics research predominantly reference and are cited by articles within the same field. For instance, in 2016, approximately 60% of all citations received by theory articles from economics articles originated from other theory papers, and about 70% of their references to other economics articles were directed towards other theory papers. The only exception to this pattern is evident in applied theory articles. When examining trends over time, the inclination of articles to be cited by or to reference articles from their own field has mostly intensified over the years.

Summary and conclusions

Our analysis indicates that certain fields demonstrate an increasing trend towards specialisation, while others may show the opposite. Both theory and econometric methods have exhibited a narrowing focus on specific research topics since the 1990s, suggesting a tendency towards specialisation. For theory articles, a negligible rise in the share of extramural citations is observed. However, the share of citations coming from other fields of economics research has decreased. These two trends suggest that theory articles are becoming more specialised. For econometric methods articles, both the share of extramural citations received and the share of citations coming from other fields of economics research have decreased, which also suggest increasing specialisation.

Applied economics research seems to have become more multidisciplinary, covering a wider breadth of research topics and gaining more citations from both other fields of study and other fields of economics research.

The case of applied theory articles is somewhat in the middle. Although citation patterns indicate a potential specialisation in this field, the upward trends in the breadth of topics covered suggest the opposite, making it difficult to make a definitive statement regarding specialisation in this particular field of economics research.

References

Anauati, V, S Galiani and R H Gálvez (2016), “Quantifying the Life Cycle of Scholarly Articles across Fields of Economic Research”, Economic Inquiry 54(2): 1339–55.

Anauati, V, S Galiani and R H Gálvez (2020), “Differences in Citation Patterns across Journal Tiers: The Case of Economics”, Economic Inquiry 58(3): 1217–32.

Anderson, K A and S Richards-Shubik (2022), “Collaborative Production in Science: An Empirical Analysis of Coauthorships in Economics”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 104(6): 1241–55.

Angrist, J, P Azoulay, G Ellison, R Hill and S Feng Lu (2017), “Economic Research Evolves: Fields and Styles”, American Economic Review 107(5): 293–97.

Angrist, J, P Azoulay, G Ellison, R Hill and S Feng Lu (2020), “Inside Job or Deep Impact? Extramural Citations and the Influence of Economic Scholarship”, Journal of Economic Literature 58(1): 3–52.

Backhouse, R and B Cherrier (2014), “Becoming Applied: The Transformation of Economics after 1970”, The Center for the History of Political Economy Working Paper Series No. 2014-15.

Becker, G S and K M Murphy (1992), “The Division of Labor, Coordination Costs, and Knowledge”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107(4): 1137–60.

Beltagy, I, K Lo and A Cohan (2019), “SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text”, in Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 3615–20, Hong Kong, China: Association for Computational Linguistics.

Blei, D M, A Y Ng and M I Jordan (2003), “Latent Dirichlet Allocation”, The Journal of Machine Learning Research 3: 993–1022.

Galiani, S, R H Gálvez and I Nachman (2023), “Unveiling Specialization Trends in Economics Research: A Large-Scale Study Using Natural Language Processing and Citation Analysis”, NBER Working Paper 31295.

Hamermesh, D S (2013), “Six Decades of Top Economics Publishing: Who and How?”, Journal of Economic Literature 51(1): 162–72.

Hamermesh, D S (2018), “Citations in Economics: Measurement, Uses, and Impacts”, Journal of Economic Literature 56(1): 115–56.

Hastie, T, R Tibshirani, and J H Friedman (2009), The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd edition, Springer Series in Statistics, New York, NY, USA: Springer.

Hu, D J (2009), “Latent Dirichlet Allocation for Text, Images, and Music”, University of California, San Diego.

Jurafsky, D and J H Martin (2009), Speech and Language Processing (2nd Edition), Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Kinney, R, C Anastasiades, R Authur, I Beltagy, J Bragg, A Buraczynski, I Cachola, et al. (2023), “The Semantic Scholar Open Data Platform”, arXiv 2301.10140.

Panhans, M T and J D Singleton (2017), “The Empirical Economist’s Toolkit: From Models to Methods”, History of Political Economy 49 (Supplement): 127–57.

Putnam, H (1979), “The ‘Corroboration’ of Theories”, in Mathematics, Matter and Method: Philosophical Papers, 2nd edition, 1: 250–269, Cambridge University Press.

Ramaley, F (1930), “Specialization in Science”, Science 72 (1866): 325–26.

Reeves, S, M Albert, A Kuper and B D Hodges (2008), “Why Use Theories in Qualitative Research?”, BMJ 337.

Walsh, J P and N G Maloney (2007), “Collaboration Structure, Communication Media, and Problems in Scientific Work Teams”, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12(2): 712–32.

Wray, K B (2005), “Rethinking Scientific Specialization”, Social Studies of Science 35(1): 151–64.

Ziman, J M (1987), Knowing Everything about Nothing: Specialization and Change in Research Careers, Cambridge University Press.