The US federal minimum wage is the baseline labour market protection for low-wage workers. Debates rage over how high it should be, in policy and in academia (e.g. Roth et al 2022, Cazes and Garnero 2023).

But a minimum wage is only effective to the degree it is actually paid – and research suggests that minimum wage non-compliance is very common. Random Department of Labor inspections of fast food outlets over 2001-2005, for example, found 40% in violation of Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) minimum wage or overtime provisions, and random garment industry inspections in 2015-2016 found FLSA violations in 85% of workplaces (Weil 2014, 2018).

In a new paper (Stansbury 2024), I compile case-level data on all FLSA violations identified by the Department of Labor since 2005 – combining publicly available data obtained in a Freedom of Information request. I use these data to ask: What incentive do US firms have to comply with the federal minimum wage? This question is important to understand the efficacy of existing minimum wage legislation, as well as to interpret other minimum wage research, including estimates of disemployment effects.

How to quantify a firm’s incentive to comply with the minimum wage? A long tradition in economics applies a cost-benefit framework to compliance decisions, suggesting that a profit-maximising company complies with the law if the extra profits made by breaking the law are less than the expected costs (Becker 1968). Taking this cost-benefit approach, I use data on penalties levied on violators to infer the penalties firms can expect to face under different scenarios – and thus, to estimate the degree to which firms have an incentive to comply with the minimum wage, under different assumptions about the probability of detection.

While the law allows for large penalties, few firms face penalties over and above paying the wages that they owed

The FLSA requires that all firms who underpay the minimum wage pay the back wages owed. They can also be required to pay an equal amount in liquidated damages. Willful or repeat violators can be charged a civil monetary penalty. In certain cases, the ‘hot goods provision’ can be used to embargo goods made in violation of the FLSA. And the most serious violators can be referred for criminal prosecution.

Yet, my analysis of the Department of Labor data shows that most firms face minimal costs for underpaying the minimum wage, over and above paying workers the wages originally owed.

Liquidated damages can in theory be levied on a large share of minimum wage violations. They were, however, almost never levied in DOL cases prior to 2012. This policy has changed in more recent years (Weil 2018). By 2022/2023, more than 30% of cases concluded had liquidated damages assessed. The remaining two thirds did not.

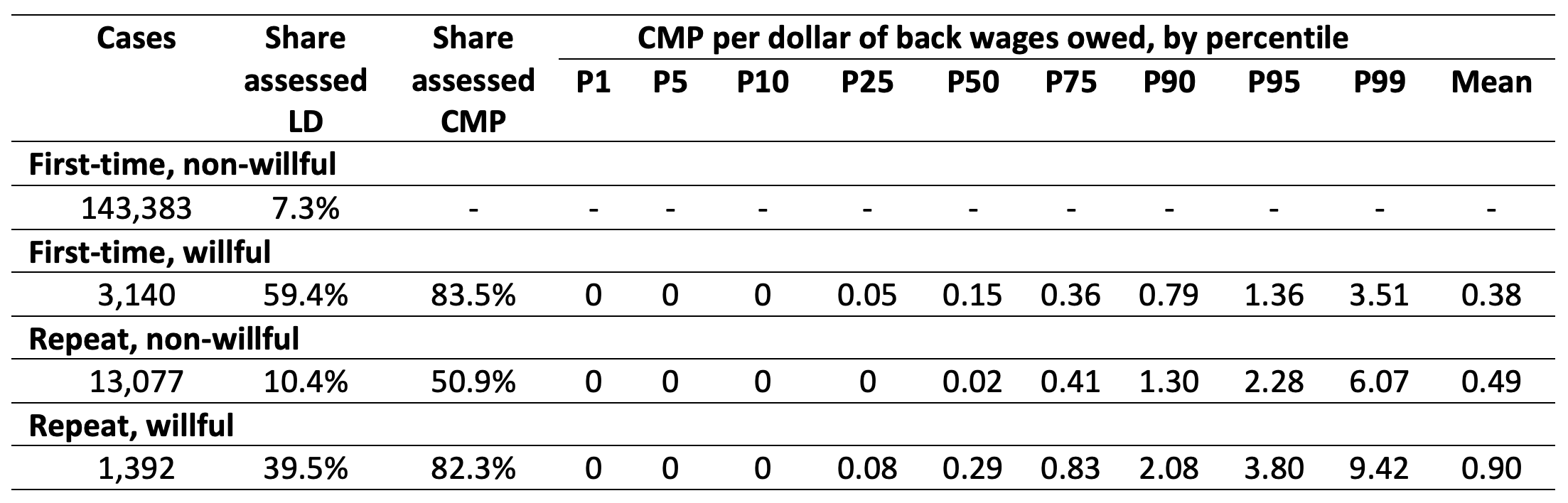

Willful and/or repeat violators may be required to pay a civil monetary penalty. But the vast majority of violations are not eligible for these penalties: 91% of violations detected by the DOL are first-time violations and of these, only 2% are deemed willful. That is, over 90% of violations are not eligible for any civil monetary penalty at all (at least under current legal interpretations of the definition of ‘willful’). Even among the repeat and/or willful violations eligible for a penalty, nearly half are charged no penalty. And even in the cases where civil monetary penalties are assessed, the amounts are small: the median repeat, non-willful violator in 2005-2023 was required to pay a penalty worth only 2 cents per dollar of back wages owed, and the median first-time willful violator was required to pay a penalty worth 15 cents per dollar of back wages owed. (Table 1). All this, taken together, means that only 6.5% of DOL-identified FLSA violations had any civil monetary penalty at all levied, and only 1.4% of cases received a penalty worth more than $1 per dollar of wages.

The ‘hot goods provision’ is almost entirely used in the garment industry (Weil 2018); among violations in other industries, the provision was used in only 0.15% of cases over 2005-2023.

Finally, criminal prosecutions are vanishingly rare: only 38 criminal convictions have occurred for violations of FLSA minimum wage or overtime provisions (sections 206, 207, 211C, 215, 216) over 1994-2020, according to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics and Federal Criminal Case Processing Statistics. While the FLSA allows for fines of up to $10,000 and prison sentences of up to 6 months in criminal convictions, in practice fines were levied in only four cases, and none led to any prison time. Thus, among willful violations detected by the DOL, there was less than a 0.7% chance of a criminal conviction and a 0.08% chance of a criminal conviction with a fine.

Table 1 Liquidated damages and civil monetary penalty assessments in concluded Department of Labor FLSA investigations where back wages were owed, 2005-23, by violation type

Source: Department of Labor WHISARD database, all concluded WHD actions FY 2005 to July 2023

Note: “LD” = liquidated damages. “CMP” = civil monetary penalty.

Department of Labor investigations are not the only channel by which FLSA minimum wage violators can be identified: they can also be taken to court by employees in an individual or collective action. In this case, the employees will receive back wages plus an equal amount in liquidated damages. A major cost to violating firms is attorney fees: both their own, and the fees of the employee(s) if the employer loses the case. No civil monetary penalties can be levied in FLSA court cases.

Average penalty levels are far too low to give most firms an incentive to comply

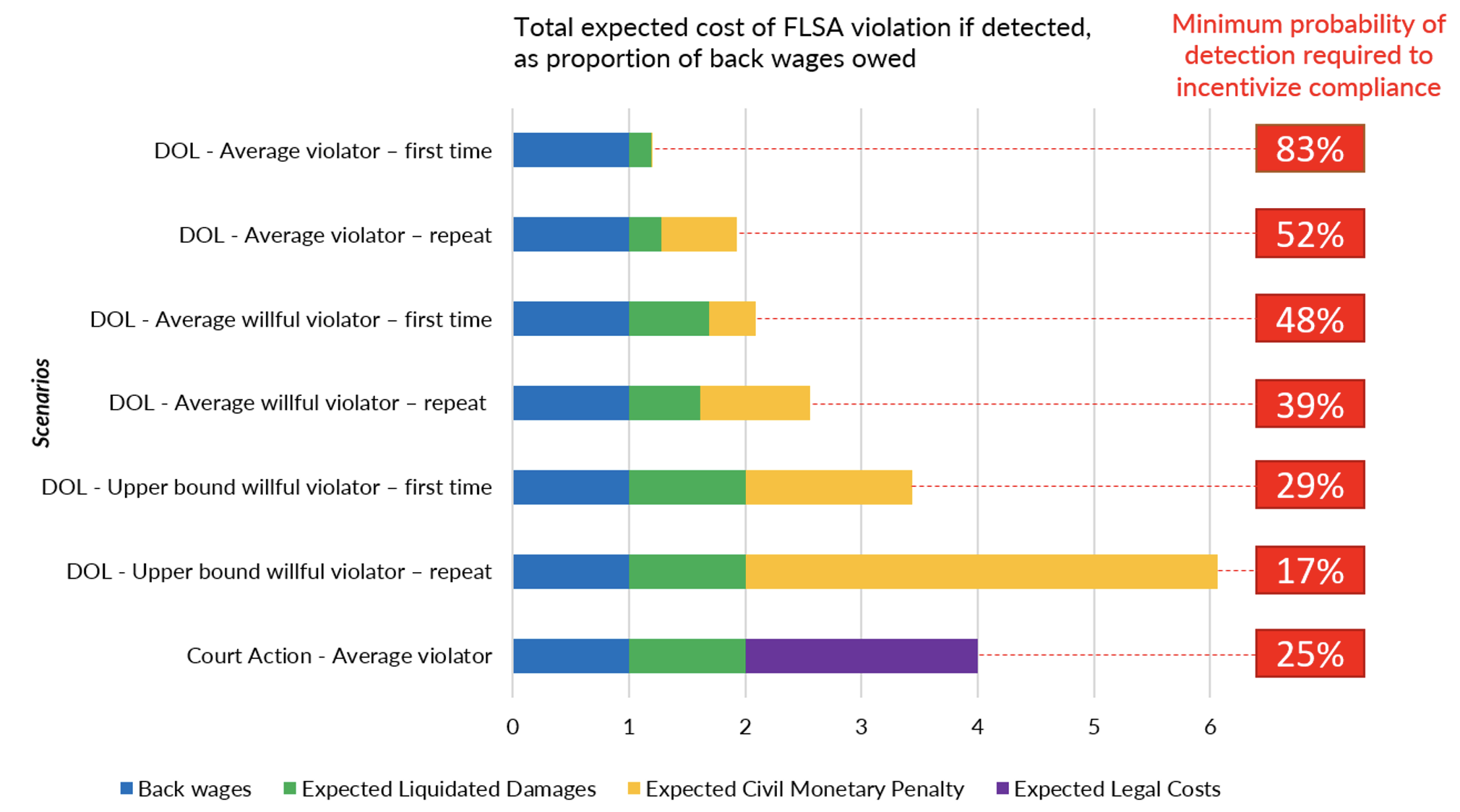

With the data above, I infer the minimum probability of detection firms must expect, to have an incentive to comply. This is simply the reciprocal of the expected penalty per dollar of wages owed (Chang and Ehrlich 1985). I consider seven possible scenarios firms might face. In Figure 1, I illustrate for each scenario (1) the expected cost the firm will face if their violation is detected, as a share of back wages owed, and (2) the minimum probability of detection that the firm must expect to have an incentive to comply.

For a DOL investigation, the most likely scenarios are the ‘Average violator’ scenarios. As the figure shows, the average first-time violator faces total costs of $1.205 per dollar of back wages owed, meaning that they would need to expect an 83% chance of detection to incentivise compliance. If the violator knows that their violation would be deemed willful if detected, the average penalty rises to $2.09 per dollar of back wages owed – but this still means that the firm would need to expect a 48% chance of detection to incentivise compliance.

Costs are higher in court, since we estimate that any attorney fee awards plus the employer’s own legal costs combined would amount to around twice the total value of back wages owed (although this can vary widely). In court, we expect an average violator to face a cost of $4 per dollar of back wages owed, meaning they would need to expect a 25% chance of a successful court case against them to have an incentive to comply.

Figure 1 Incentives to comply with the FLSA under different scenarios

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on DOL enforcement data and data from FLSA cases (obtained using Westlaw).

Actual probabilities of detection are likely substantially lower than this. Using data on inspections and violations in fast food from Weil (2014b), I estimate that the average violating establishment has a 1.4% chance of being detected through a targeted DOL inspection in a given year – or a 4.2% chance over three years, the maximum length for which back wages can be claimed. That is, even under relatively effective targeting, detection probabilities would need to increase by more than an order of magnitude to reach the range of 48%-83% which my estimates suggest is required to incentivise compliance at current penalty levels. And while violations are frequently detected through worker complaints or court actions, these cannot be relied on to surface underpayment, particularly from the most vulnerable workers: workers may fear retaliation or job loss, or may not know their employer’s pay practices are illegal (e.g. Weil and Pyles 2006, Bobo 2011).

Higher penalties and greater enforcement are needed to ensure minimum wage compliance

For many firms in the US, then, the existing penalty and enforcement system for the FLSA does not create sufficient incentive to comply. Compliance incentives can be improved by increasing penalties and/or the probability of detection. The two are inversely related: to create an effective deterrent the expected penalty must increase exponentially as the probability of detection declines. My estimates suggest increases on both margins are needed.

When considering appropriate penalties, it is illustrative to note that the penalties firms face for underpaying workers – wage theft – are far smaller than the penalties individuals face for theft of items of equivalent value. Shoplifting goods worth $2,500 or more can lead to felony charges and imprisonment in every state (Traub 2017). Over 2005-2020, the DOL found more than 16,000 cases of minimum wage underpayment, and more than 76,000 cases of overtime underpayment, worth more than $2,500. The total value underpaid to workers across these was nearly $570 million. In this time there were 26 criminal convictions, 3 criminal fines, and no prison sentences for FLSA violations.

My work focuses on the expected penalties levied by the legal system, and excludes reputation costs. Enforcement agencies can and do leverage companies’ reputation concerns to incentivize compliance, over and above penalties (Ji and Weil 2015, Johnson 2020). But it is insufficient for a law to rely only on reputation: if so, workers at unscrupulous companies suffer, and ethical companies are at a competitive disadvantage.

Effective deterrence will only become more important as the federal minimum wage is increased. In real terms, the federal minimum wage is at its lowest level in 66 years (Cooper et al 2022) and, as a result, it applies to relatively few workers. If it was raised to $15, as per recent proposals, an estimated one in six US workers would be affected (Zipperer 2023) – with a correspondingly greater noncompliance problem (Clemens and Strain 2024).

References

Becker, G S (1968), "Crime and punishment: An economic approach", The economic dimensions of crime, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 13-68.

Bernhardt, A, R Milkman, N Theodore, D D Heckathorn, M Auer, J DeFilippis, A Luz González, V Narro, and J Perelshteyn (2009), "Broken laws, unprotected workers: Violations of employment and labor laws in America's cities".

Bobo, K (2011), Wage Theft in America (revised ed).

Cazes, S and A Garnero (2023), “Minimum wages in times of high inflation”, VoxEU.org, 8 August.

Chang, Y-M, and I Ehrlich (2009), "On the economics of compliance with the minimum wage law", Journal of Political Economy 93(1): 84-91.

Clemens, J, and M R Strain (2024), “The economics and implications of compliance with minimum wages”, VoxEU.org, February.

Cooper, D, and T Kroeger (2017), “Employers steal billions from workers’ paychecks each year”, Economic Policy Institute, May.

Eastern Research Group (2014), “The social and economic effects of wage violations: Estimates for California and New York”, prepared for the U.S. Department of Labor, December.

Galvin, D J (2016), "Deterring Wage Theft: Alt-Labor, State Politics, and the Policy Determinants of Minimum Wage Compliance", Perspectives on Politics 14(2): 324-350.

Roth, D, T Seidel, and G Ahlfeldt (2022), “Optimal Minimum Wages”, VoxEU.org, 16 February.

Stansbury, A (2024), “Incentives to Comply with the Minimum Wage in the US and UK”, ILR Review.

Weil, D (2014), Improving Workplace Conditions Through Strategic Enforcement, Report to the Wage and Hour Division.

Weil, D (2018), "Creating a strategic enforcement approach to address wage theft: One academic’s journey in organizational change", Journal of Industrial Relations 60(3): 437-460.

Weil, D, and A Pyles (2006), "Why Complain-Complaints, Compliance, and the Problem of Enforcement in the US Workplace", Comparative Labor Law & Policy 27: 59.

Zipperer, B (2023), “Low-wage workforce tracker”.