At most central banks, monetary policy is determined by a committee. A potential advantage of committee decision-making is that ‘two heads are better than one’. But the nature of a committee also raises a host of questions, positive and normative. Earlier Vox columns have discussed issues related to committee composition, such as the role of the appointment process for the US Federal Reserve System’s monetary policy committee, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) (Bordo and Istrefi 2018), and the desirability of diversity (see McMahon and Hansen 2010 related to internal and external members, Eijffinger et al. 2013 with regard to professional background, and Masciandaro et al. 2018 on gender). How transparency may induce monetary policy committee members to be better prepared has been discussed by Hansen et al. (2014), and how to decide on voting rules is studied by Claussen and Røisland (2015). An organisational feature that is receiving considerable attention from lawmakers in the US, but has not been studied much by academics, is the rotation of voting rights. The rotation scheme used on the FOMC is the topic of this column. In a new paper (Ehrmann et al. 2021), we investigate how voting right rotation affects behaviour between and during FOMC meetings and whether the reaction of the financial market to a speech depends on the voting status of the speaker.

Voting right rotation on the FOMC

The seven members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York are permanent members of the FOMC and vote at every meeting. The remaining four votes are assigned to four groups of 11 Federal Reserve districts. Which district in each group has the right to vote is determined by an annual mechanical rotation scheme which has been in place since 1943. As a result, Reserve Bank presidents of these districts experience years with and without the right to vote. Rotation is without exclusion, i.e. non-voting presidents attend the meetings and participate in the discussions – their only difference to voting presidents is that they do not vote.

Two competing hypotheses about whether the voting status of presidents affects their behaviour

In our paper, we formulate two hypotheses.

- First, the loss compensation hypothesis is inspired by the literature on influence activities and strategic information transmission (Crawford and Sobel 1982, Milgrom and Roberts 1986, 1988). It maintains that in years without the right to vote, presidents seek to compensate for the loss of the formal voting right by making more intense use of intermeeting speeches and meeting interventions.

- Second, the gain enhancement hypothesis is inspired by the literature on decision-making authority in organizations (Aghion and Tirole 1997, Baker Gibbons and Murphy 1999). It maintains that in years with the right to vote, presidents are more committed and involved in the decision-making process and this leads them to make more intense use of intermeeting speeches and meeting interventions.

A Reserve Bank president is expected to bring intelligence about regional economic conditions to the FOMC discussions. Moreover, they are the chief executive officer of the Bank and are accountable to the Bank’s board of directors. These boards have strong ties with the districts’ economy and community in general. In line with this role, earlier research (Meade and Sheets 2005, Chappell et al. 2008) has highlighted that regional economic conditions influence the speeches and policy preferences of Reserve Bank presidents. With regard to the variation of their voting rights, the loss-compensation hypothesis predicts that the tone and number of intermeeting speeches and the tone and length of meeting interventions depend more strongly on regional economic conditions in years without than in years with the right to vote. The gain enhancement hypothesis maintains the opposite, i.e. that their dependence becomes stronger in years with the right to vote.

To test our hypotheses, we parse the transcripts of 160 FOMC meetings and around 2,800 speeches during the period 1994-2013.

Voting status changes presidents’ behaviour between and during meetings

The patterns in the data support the gain enhancement hypothesis and go against the loss compensation hypothesis, both when we study the intermeeting speeches and the meeting interventions. The number of speeches and the tone of speeches and meeting interventions depend more strongly on regional economic circumstances in years a president has the voting right than in years without. The stronger dependence on regional conditions in voting years is even larger after FOMC meetings with dissenting votes. This further supports the gain-enhancement hypothesis because in times of high disagreement on the FOMC, having the right to vote is particularly valuable.1

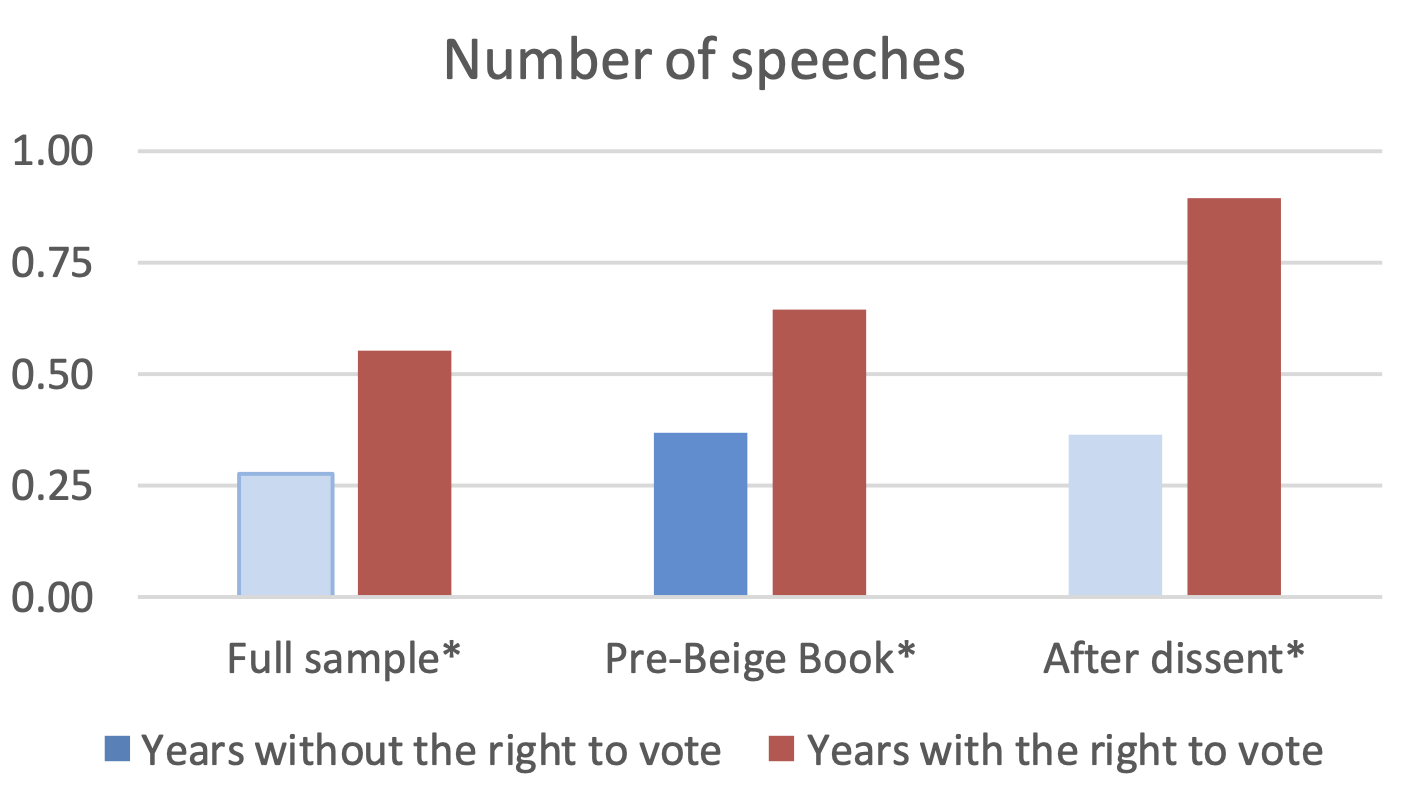

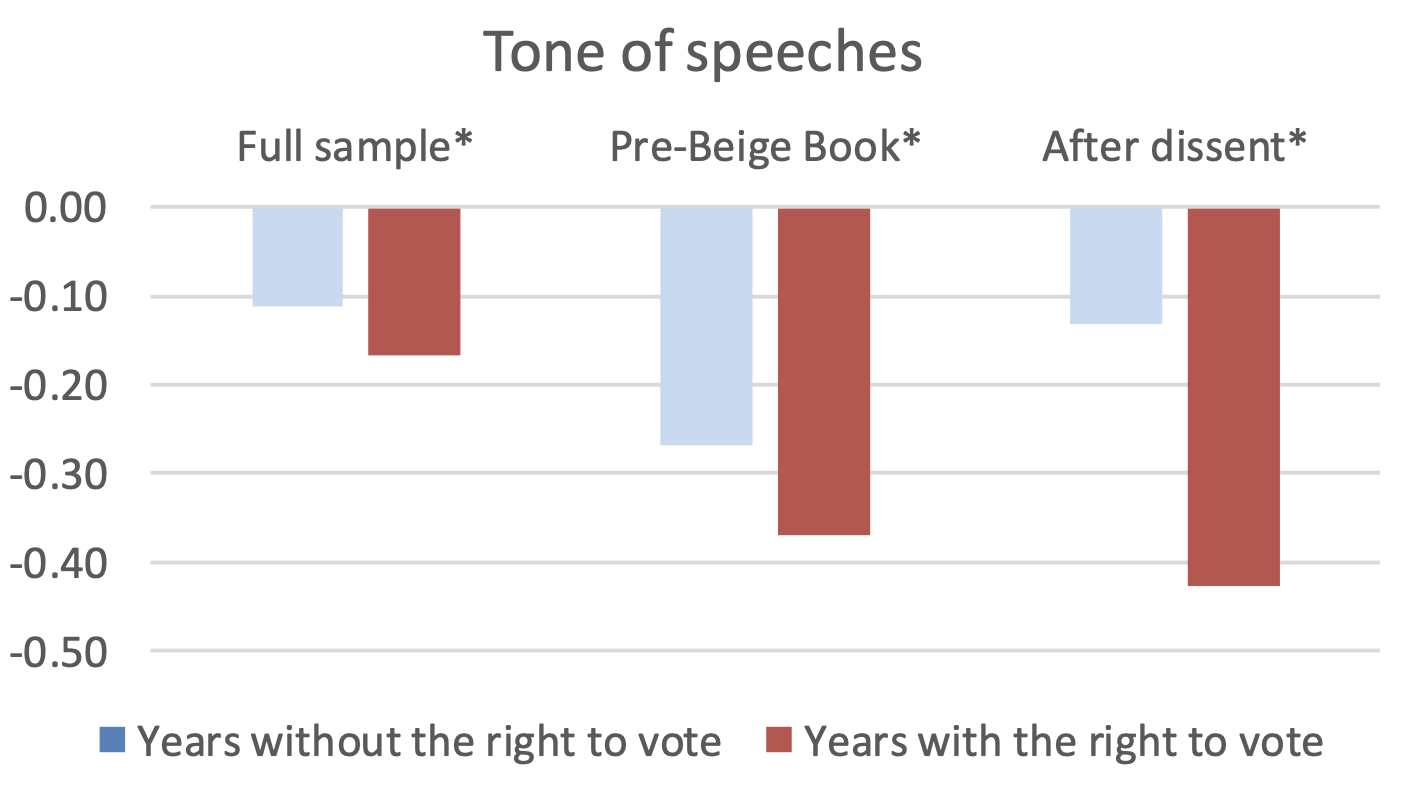

Figure 1 The responsiveness of speeches to regional economic conditions

Notes: The figure shows the responsiveness of speeches to regional unemployment, for the number of speeches (upper panel) and the tone of speeches (lower panel), as estimated for years in which a president is without the right to vote (blue bars) and years with the right to vote (red bars), for the full sample, for the time period before the release of the Beige Book, and for the full intermeeting period following an FOMC meeting with dissent. Dark shaded bars are statistically significant at least at the 10% significance level. Cases where the difference between years with and without the right to vote is statistically significant at least at the 10% significance level are denoted with an asterisk in the axis labels.

Asset price reactions to speeches show a vote discount

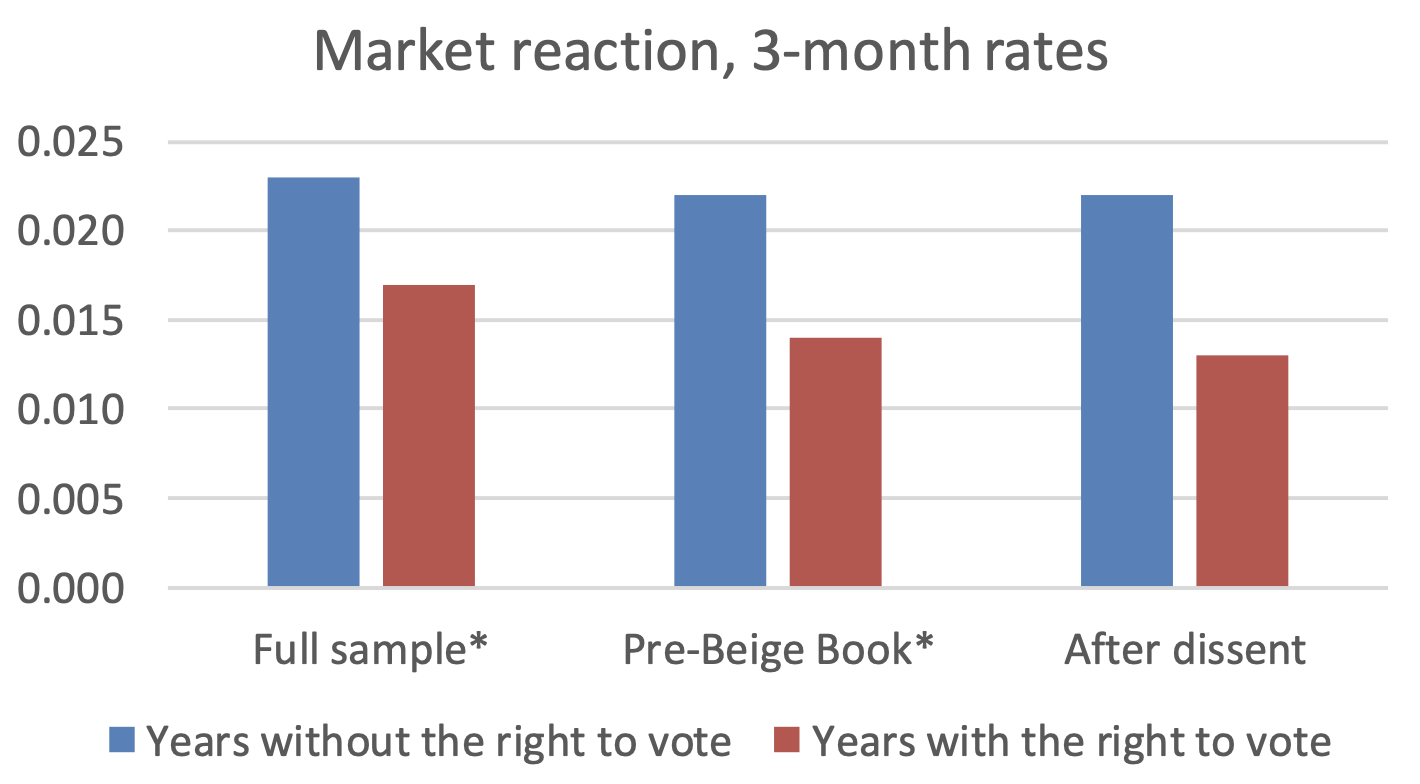

These differences in behaviour affect how financial markets react to speeches delivered between meetings. We measure the market reaction to presidents’ speeches by the absolute daily change in Treasury yields, with maturities varying from three months to five years. As shown in Figure 2, we find a ‘vote discount’. The market responds systematically less to speeches in years presidents vote than in years they do not vote. The estimated effect is large – in our benchmark estimation, the discount equals 26% of the average absolute daily change for three-month rates and still amounts to 11% for five-year rates.

Figure 2 The responsiveness of three-month constant maturity Treasury yields to speeches by Reserve Bank presidents in the voting rotation

Notes: The figure shows the responsiveness of 3-month constant maturity Treasury yields to speeches by Reserve Bank presidents in the voting rotation, as estimated for years in which a president is without the right to vote (blue bars) and years with the right to vote (red bars), for the full sample, for the time period before the release of the Beige Book, and for the full intermeeting period following an FOMC meeting with dissent. Cases where the difference between years with and without the right to vote are statistically significant at least at the 10% significance level are denoted with an asterisk in the axis labels.

The vote discount might seem surprising – after all, formally a president is more influential in years with the right to vote. We argue that this vote discount is consistent with the difference in behaviour due to voting status. Under the assumption that participants in the US treasury market are more interested in national than in regional information, our argument is that markets can extract more relevant information from a speech given by a president in years without the right to vote than in years with the right to vote. In further support of this argument, we find that the vote discount by the market is especially large for speeches given before the publication of the Beige Book with district-level information (35% for 3-month rates) or after meetings with dissent (40% for 3-month rates). These are precisely the speeches that respond most strongly to the regional economy when a president has voting status.

Implications for ongoing policy debates

Our contribution is descriptive – a normative framework should be used to assess whether this change in behaviour is desirable and, if not, how it could be mitigated. Still, our analysis sheds light on possible consequences of recent proposals for reforming the FOMC.

Most related to our analysis, Vissing-Jorgensen (2020) and Bills H.R. 4759 and H.R. 6741 of the 115th Congress propose, among other things, to remove the voting right rotation and give the Reserve Bank presidents permanent voting rights.2 If presidents get a permanent voting right on the FOMC, they could become even more committed. This might further strengthen the gain-enhancement effects we find in the data.

Removing the voting rights for Reserve Bank presidents altogether, as proposed by Conti- Brown (2016), may lead them to seek other ways to influence policy. After all, the regional information that Reserve Bank presidents presently bring to the table forms a vital part of the meeting input and will continue to be sought for. This gives them a natural role in the deliberation process – if not during, then prior to the meeting.

Our analysis highlights the fact that voting rights affect the behaviour of Reserve Bank presidents and the financial market response to Fed communication. These are aspects that should be considered when deciding on possible reforms of the voting right allocation in the FOMC.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column present the authors’ personal opinions and do not necessarily reflect the views of the ECB or the Eurosystem.

References

Aghion, P, and J Tirole (1997), “Formal and real authority in organizations”, Journal of Political Economy 105(1): 1-29.

Baker, G, R Gibbons, and K J Murphy (1999), “Informal authority in organizations”, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 15(1): 56-73.

Bordo, M, and K Istrefi (2018), “The making of the Federal Open Market Committee: Ideology and politics”, VoxEU.org, 20 August.

Chappell Jr, H W, R R McGregor, and T A Vermilyea (2008), “Regional economic conditions and monetary policy”, European Journal of Political Economy 24(2): 283-293.

Claussen, C A, and Ø Røisland (2015), “Monetary policy committees: Voting on premises versus decisions”, VoxEU.org, 14 May.

Conti-Brown, P (2016), The power and independence of the Federal Reserve, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Crawford, V P, and J Sobel (1982), “Strategic information transmission”, Econometrica 50(6): 1431-1451.

Ehrmann, M, R Tietz, and B Visser (2021), “Voting right rotation, behavior of committee members and financial market reactions: Evidence from the U.S. Federal Open Market Committee”, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 16213.

Eijffinger, S, R Mahieu, and L Raes (2013), “Policy preferences of central bankers and the design of a monetary-policy committee”, VoxEU.org, 7 May.

Hansen, S, M McMahon, and A Prat (2014), “Central bank transparency and committee deliberation”, VoxEU.org, 20 June.

Masciandaro, D, P Profeta and D Romelli (2018), “Why women matter in monetary policymaking”, VoxEU.org, 25 September.

McMahon, M, and S Hansen (2010), “What do external experts bring to the table? Evidence from the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee”, VoxEU.org, 25 September.

Meade, E E, and D N Sheets (2005), “Regional influences on FOMC voting patterns”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 37(4): 661–677.

Milgrom, P, and J Roberts (1986), “Relying on the information of interested parties”, Rand Journal of Economics, 17 (1), 18-32.

Milgrom, P, and J Roberts (1988), “An economic approach to influence activities in organizations”, American Journal of Sociology 94: S154-S179.

Vissing-Jorgensen, A (2020), “Central banking with many voices: the communications arms race”, Conference Proceedings, 23rd Annual Conference of the Central Bank of Chile.

Endnotes

1 Instead, the loss-compensation hypothesis would predict the opposite, i.e., that non-voters react more strongly after dissents because not having the right to vote is particularly costly when disagreement is high.

2 The proposal by Vissing-Jorgensen (2020) also calls for a reduction of the number of Reserve Bank districts.