Over the past several decades, industrialised nations have experienced a notable decline in manufacturing employment, sparking concerns regarding the economic prospects of regions historically dependent on these industries (IMF 2018, Benedetto et al. 2018). The Rust Belt in the US, Northern England, and the Ruhr Valley in Germany stand as stark examples of areas grappling with the repercussions of deindustrialisation, characterised by widespread job losses, economic downturns, and social challenges (Autor et al. 2013, Charles et al. 2019). In response to these challenges, policymakers have introduced various place-based initiatives aimed at revitalising affected regions (Wolman et al. 2017, Bartik et al. 2018). However, the efficacy of such policies remains uncertain due to limited evidence on the spatial heterogeneity of deindustrialisation impacts and the factors influencing local economic recovery (Glaeser 2009, Rice et al. 2021).

To address these gaps, in a recent paper (Gagliardi et al. 2023) we delve into the employment consequences of deindustrialisation across 1,993 cities in France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, and the US. We compiled a novel dataset obtained by combining and harmonising several country-specific data sources for the six countries under consideration. Our geographical unit of analysis is a local labour market (LLM). The exact definition varies across countries, but in all six countries in our sample, LLMs are defined based on residential and commuting patterns. Specifically, LLMs are defined to reflect an economic unit, rather than administrative boundaries. In each country, the boundaries of an LLM are designed so that the majority of its residents live and work within the LLM. For each country in our sample, we gathered information on employment by industry, education, and population starting from the 1960s. Additionally, we complemented our data with information on the locations of historical colleges or universities, which are defined as colleges or universities that existed between 50 and 20 years before the beginning of our period of analysis. For France, Germany, Italy, and the UK, the data on location and opening date come from the European Tertiary Education Register (ETER), which provides information on higher education institutions (HEIs) in Europe. For the US, we used data collected by Currie and Moretti (2003) which report the addresses and opening dates of all two-year and four-year colleges existing in the country in 2000. We exploit this information to address endogeneity concerns by constructing, for all LLMs in our sample (excluding those in Japan), a measure of driving distance to the closest university.

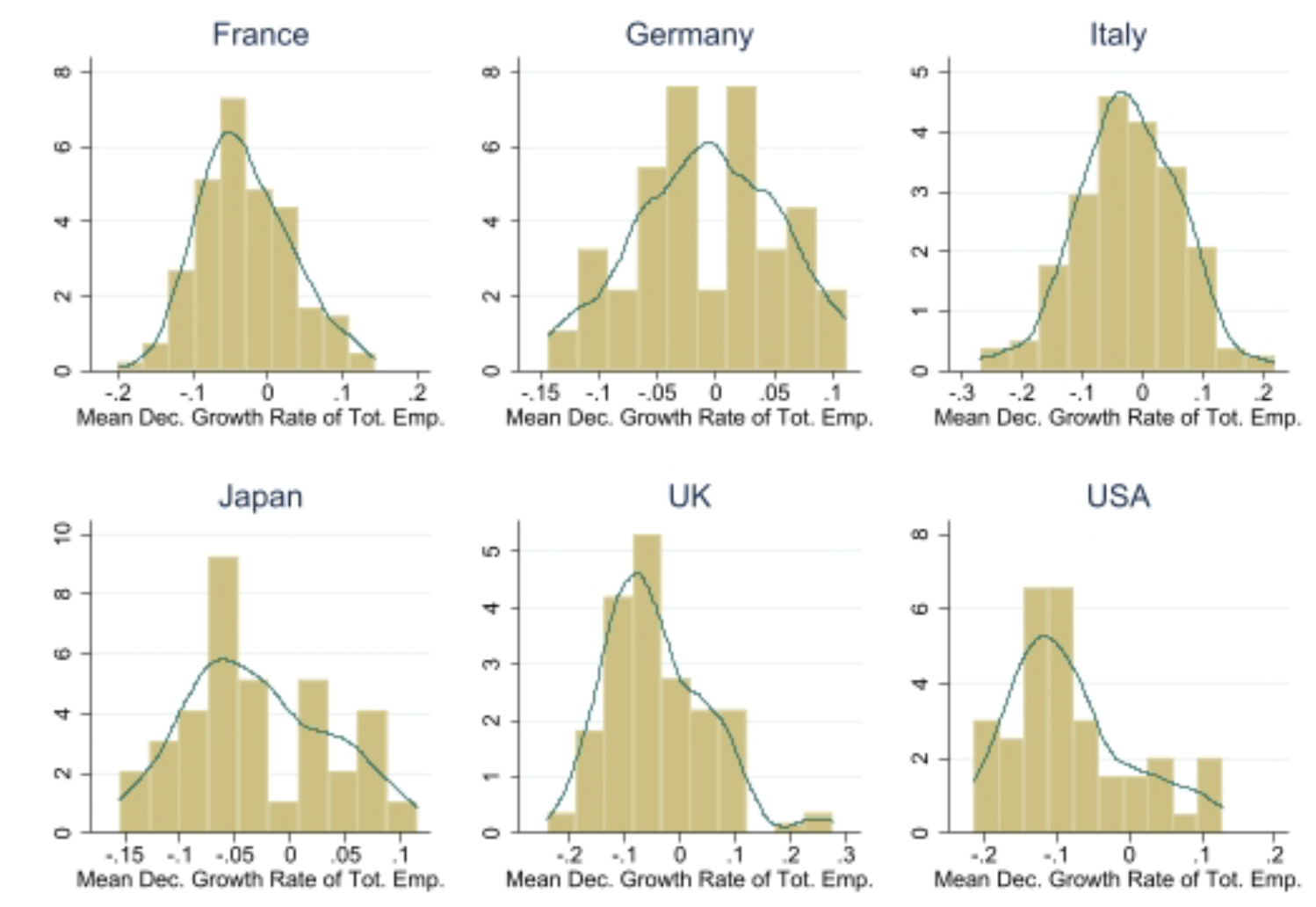

Our empirical investigation commences by providing a descriptive account of the geographic heterogeneity in employment changes during the deindustrialisation period. Focusing on former manufacturing hubs characterised by a high share of manufacturing employment relative to national distributions, we observe diverse trajectories among these cities. While overall employment declined in most hubs, a notable proportion experienced full recovery, surpassing peak employment levels. Our analysis indicates that despite the loss of manufacturing jobs, 34% of former manufacturing hubs across the six countries achieved full recovery by 2010 (Figure 1). This suggests that for every Detroit or Liverpool facing employment decline, there exists a former manufacturing hub where employment not only recovers but exceeds pre-deindustrialisation levels.

Furthermore, our study reveals significant cross-country variation in the extent of employment recovery. Germany stands out with the highest share of former manufacturing hubs achieving full recovery, underscoring comparatively favourable outcomes for these regions. In contrast, the US exhibits lagging recovery rates, particularly evident in Rust Belt communities, indicating relatively poorer outcomes compared to counterparts in other industrialised nations.

Figure 1

Does human capital soften the blow of industrial decline?

This spatial heterogeneity prompts an exploration into the determinants of employment recovery, with a focus on the role of human capital in mitigating the adverse effects of manufacturing decline and facilitating economic resurgence. We hypothesise that cities with higher initial levels of human capital were better equipped to adapt to the challenges posed by deindustrialisation and exhibit faster employment growth post-restructuring.

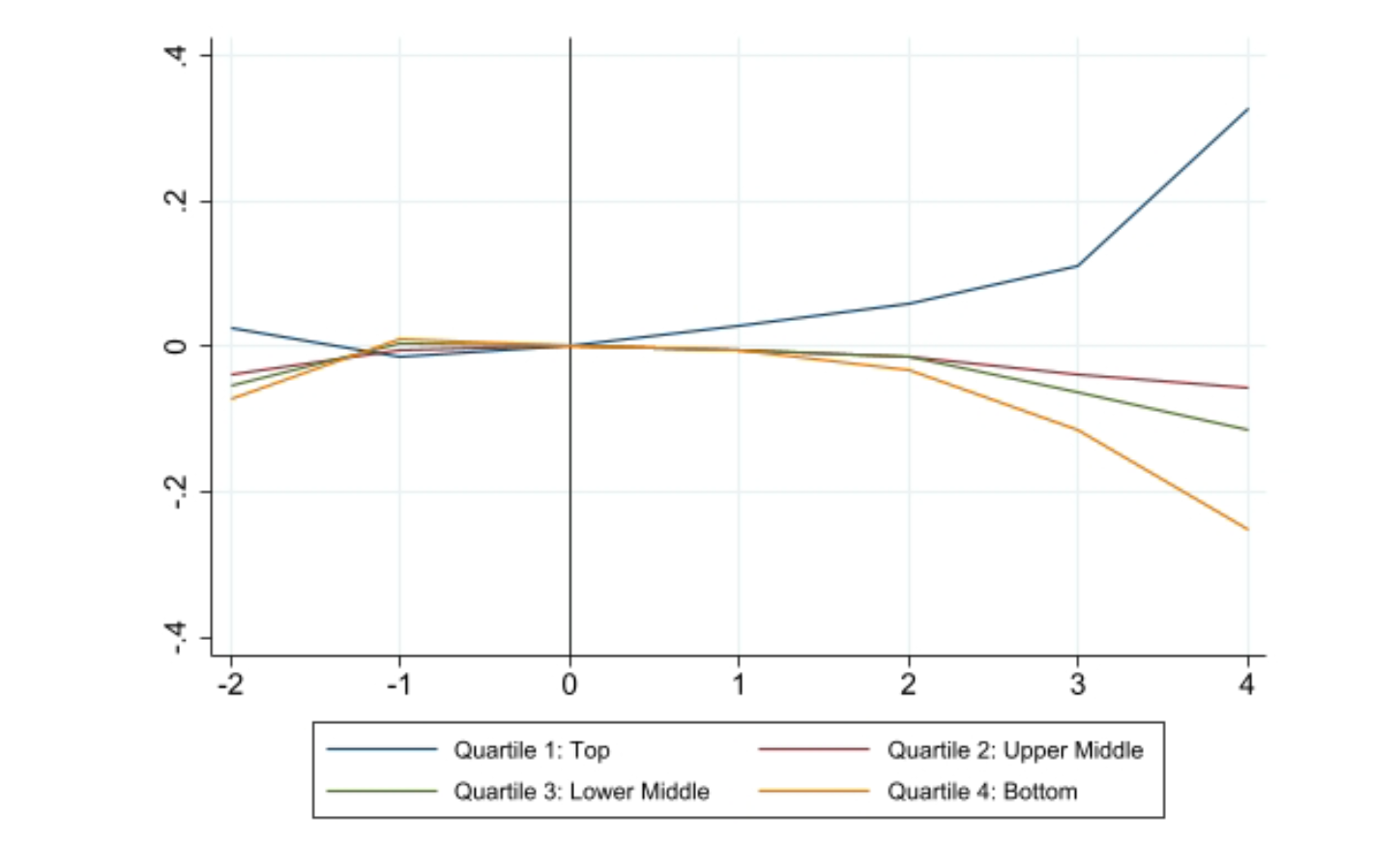

We find evidence of a strong positive relationship between the initial share of college graduates and subsequent employment growth. This relationship is particularly pronounced in the aftermath of manufacturing decline, suggesting a shift towards industries that require higher levels of human capital. Incidentally, while in the two decades before the relevant country’s manufacturing peak,

cities with a high share of college-educated workers experience a similar rate of employment growth as those with a low share of college-educated workers, after the manufacturing peak their employment trends diverge: cities with a high initial share of college-educated workers experience significantly faster employment growth (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Thus, while the local share of college graduates may not have been a significant determinant of employment growth during periods of expanding manufacturing employment, the dynamics shift during deindustrialisation. This shift likely reflects the changing nature of industries, with a greater demand for highly skilled workers in human capital-intensive sectors. In essence, the emergence of these sectors has made the local share of college graduates a crucial predictor of employment growth during times of economic transformation.

Consequently, for former manufacturing hubs, the loss of factory jobs did not inevitably result in overall employment declines. Instead, a strong local human capital base emerges as a vital factor in successfully navigating the challenges posed by manufacturing decline. This finding is exemplified by the experience of Pittsburgh. Once a powerhouse of steel production in North America, the city faced rapid decline in the 1970s. However, its robust skill base, anchored by institutions like Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh, attracted employers in sectors such as life sciences research, high technology, and education. These industries, reliant on highly skilled workers, not only helped offset the losses in manufacturing but also contributed to the city's economic revitalisation and diversification (Andes et al. 2017, Mills et al. 2022).

Our research highlights the pivotal role of human capital for local economic growth. As manufacturing jobs dwindle and industries undergo transformation, the ability of regions to adapt and thrive hinges on the skills and knowledge of their workforce. A policy implication of our findings is that investment in local colleges and universities can be a useful tool for fostering economic recovery and mitigating the adverse impacts of deindustrialisation. Such investments not only benefit individuals by enhancing their employability but also create a virtuous cycle of economic growth and prosperity for the broader community.

References

Andes, S, M Horowitz, R Helwig and B Katz (2017), “Capturing the next economy: Pittsburgh’s rise as a global innovation city”, Brookings Institution — The Bass Initiative on Innovation and Placemaking.

Autor, D, D Dorn, and G H Hanson (2013), “The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States”, American Economic Review 103(6): 2121–68.

Bartik, T J (2018), Helping manufacturing-intensive communities: What works?, Technical report, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Benedetto, J (2018), Trends in Manufacturing Employment in the Largest Industrialized Economies during 1998-2014, Technical report, USITC Executive Briefings on Trade, Washington, DC: US International Trade Commission.

Charles, K K, E Hurst, and M J Notowidigdo (2019), “Housing booms, manufacturing decline and labour market outcomes”, The Economic Journal 129(617): 209–248.

Currie, J and E Moretti (2003), “Mother’s education and the intergenerational transmission of human capital: Evidence from college openings”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4): 1495–1532.

Gagliardi, L, E Moretti and M Serafinelli (2023), “The World’s Rust Belts: The Heterogeneous Effects of Deindustrialization on 1,993 Cities in Six Countries”, NBER Working Paper 31948.

Glaeser, E L (2009), “The death and life of cities", in Making cities work: Prospects and policies for urban America, Princeton University Press.

IMF (2018), Chapter 3, Manufacturing Jobs: Implications for Productivity and Inequality.

Mills, K, C Elkins, V Gandhi, G Elanbeck and Z Gillman (2022), “Pittsburgh: A successful city?”, Harvard Business School Case 322-080.

Rice, P G and A J Venables (2021), “The persistent consequences of adverse shocks: how the 1970s shaped UK regional inequality”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 37(1): 132-151.

Wolman, H, H Wial, T S Clair and E Hill (2017), Coping with Adversity: Regional Economic Resilience and Public Policy, Cornell University Press.