Recent research has documented a steady rise in the share of unviable and unproductive (‘zombie’) firms around the world, especially since the Global Financial Crisis (Banerjee and Hofmann 2022, Albuquerque and Iyer 2023). It is also well-documented that the survival of zombie firms produces negative spillover effects to other firms competing with zombie firms, reducing overall productivity, investment, and employment in the real economy (Caballero et al. 2008, McGowan et al. 2018, Acharya et al. 2019, Banerjee and Hofmann 2022, Albuquerque and Iyer 2023). The increased zombification of the nonfinancial sector raises an important question in the context of tighter financial conditions: do tighter financial conditions allow a better allocation of resources towards more profitable and viable firms?

In a new paper, we study how the presence of zombie firms affect the transmission of monetary policy to nonfinancial firms (Albuquerque and Mao 2023). We trace out the differential response of zombie firms’ financial performance relative to non-zombies following contractionary monetary policy shocks. We find that zombie firms are less responsive to monetary policy, as evergreening incentives lead banks to offer more favorable credit conditions to zombie firms relative to healthier firms. Overall, our findings raise concerns that more productive and viable firms may be hardest hit by the ongoing tightening in financial conditions, particularly in jurisdictions where regulation and bank supervision play a limited role in preventing zombie creation.

Zombie firms are less responsive to contractionary monetary policy

Monetary policy traditionally affects firms’ cost of capital through the bank lending and the risk-taking channels (Bernanke and Gertler 1995, Kashyap and Stein 2000, Borio and Zhu 2012). According to these channels, we would expect a tightening in monetary policy to transmit more strongly to zombie firms relative to other firms, since lenders would prioritise lending to more productive firms and with healthier balance sheets. This mechanism would also be consistent with the fact that zombie firms rely more on bank debt for their funding: zombie firms would have less flexibility to find alternative sources of funding to finance their investment when interest rates increase (Becker and Ivashina 2014, Ippolito et al. 2016).

We add another layer through which monetary policy may transmit differentially to zombie firms. We conjecture that banks’ incentives to evergreen loans of zombie firms may be stronger when interest rates increase, as banks internalise a higher probability of zombie firms filing for bankruptcy when the cost of funding goes up. It is then plausible that banks may decide to extend the original loan to zombies to avoid the realization of losses. This implies that zombie firms would be less affected by a contractionary monetary policy shock — the zombie lending channel. This incentive may be stronger for weaker banks who may go out of business if their capital is not high enough to absorb the losses from zombie lending. Overall, given the competing forces and channels at work, the response of zombie firms to monetary policy remains an empirical question.

We use quarterly balance sheet data from S&P Compustat on nonfinancial listed firms for 49 countries (23 emerging markets and 26 advanced economies) over 2000-2019. We identify zombie firms by conditioning on the following indicators, as in Albuquerque and Iyer (2023): (i) interest coverage ratio (ICR) below one, (ii) leverage ratio above the median firm in the same industry, and (iii) negative real sales growth. These three conditions need to be observed for at least two consecutive years. In addition, we allow zombie firms to exit the zombie status only if at least one of the indicators is reversed for two years in a row. The two-year horizon in the entry to, and exit from, zombie status minimizes misclassification from cyclical fluctuations.

We identify exogenous variation in monetary policy conditions for a large set of countries by resorting to US monetary policy shocks. Our choice is motivated by the well-established view that US monetary policy drives the global financial cycle, and is arguably exogenous to changes in economic conditions in the rest of the world (Rey 2013, Bruno and Shin 2015). We follow the state-of-the-art high-frequency identification that uses monetary policy surprises as proxies for the true structural monetary policy shocks (Gürkaynak et al. 2005, Gertler and Karadi 2015, Nakamura and Steinsson 2018). Specifically, we isolate interest rate surprises using the movement in three-month Fed Funds Futures within a 30-minutes window around FOMC policy announcements. The identifying assumption is that no other factors could drive both the private sector behaviour and monetary policy decisions within this short interval.

To trace out the differential effects of monetary policy shocks on nonfinancial firms, we use a panel data local projection instrumental variable (LP-IV) setup. The US high-frequency monetary policy surprises act as the external instrument for the country-specific monetary policy indicator, proxied with the local one-year sovereign bond yields. We then regress several firm balance sheet indicators on the country-specific monetary policy shocks and other firm-specific controls. We also add country-sector-time fixed effects to control for all sources of shocks that may differently affect firms. Our coefficient of interest is the interaction term between a dummy variable capturing zombie firms with the country-specific monetary policy shock. This coefficient measures the differential response to a contractionary monetary policy shock of zombie firms’ financial performance relative to non-zombies’ within the same country, industry and quarter. We calibrate the shock to increase country-specific borrowing costs by 100 basis points.

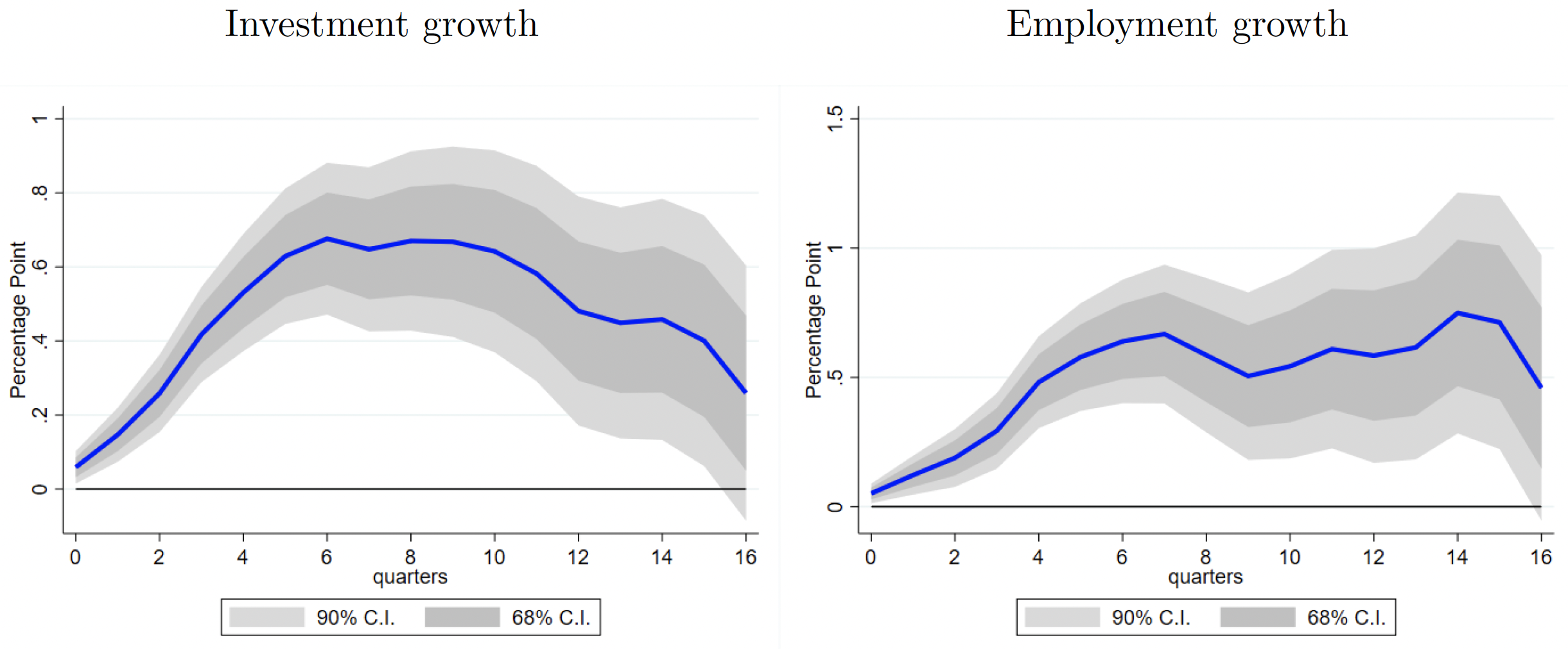

We document in the paper that, as expected, nonfinancial firms’ financial performance declines across-the-board following a contractionary monetary policy shock (Albuquerque and Mao 2023). We show our novel finding in Figure 1: investment and employment growth of zombie firms are less responsive to monetary policy shocks relative to non-zombie firms. Our estimates suggest that the response of zombie firms’ investment growth at the peak, reached after roughly two years, is around 0.7 percentage points smaller relative to non-zombies, while the response of employment growth is almost 0.8 percentage points smaller. These responses are economically important: the mean sample difference of investment growth between zombies and non-zombies is 2.6 percentage points, implying that a monetary policy shock calibrated to increase bond yields by 100 basis points leads this gap to shrink by roughly 25%.

Figure 1 Differential effect of monetary policy shocks on zombies versus non-zombies: Investment and employment

Notes: Cumulative impulse responses for zombie firms relative to non-zombies to a monetary policy shock that increases the country-specific one-year sovereign bond yields by 100 bps. The blue line is the average point estimate, and the dark (light) grey area refers to the 68% (90%) confidence bands.

The passthrough of higher interest rates to zombie firms is more limited relative to other firms

Our previous finding may challenge the conventional wisdom that firms in financial distress tend to be more responsive to monetary policy (Bahaj et al. 2022, Cloyne et al. 2023). Since zombie firms are riskier, unproductive, and with weaker balance sheets, one would expect zombie firms to respond in a similar fashion to the literature’s findings on financially constrained firms. When we use traditional metrics to capture financial constraints (age, probability of default), we indeed find that non-zombies that are financially constrained do respond more to monetary policy, in line with the literature. To be sure, our results then suggest that the behaviour of zombie firms is fundamentally different from the conventional response of financially constrained firms.

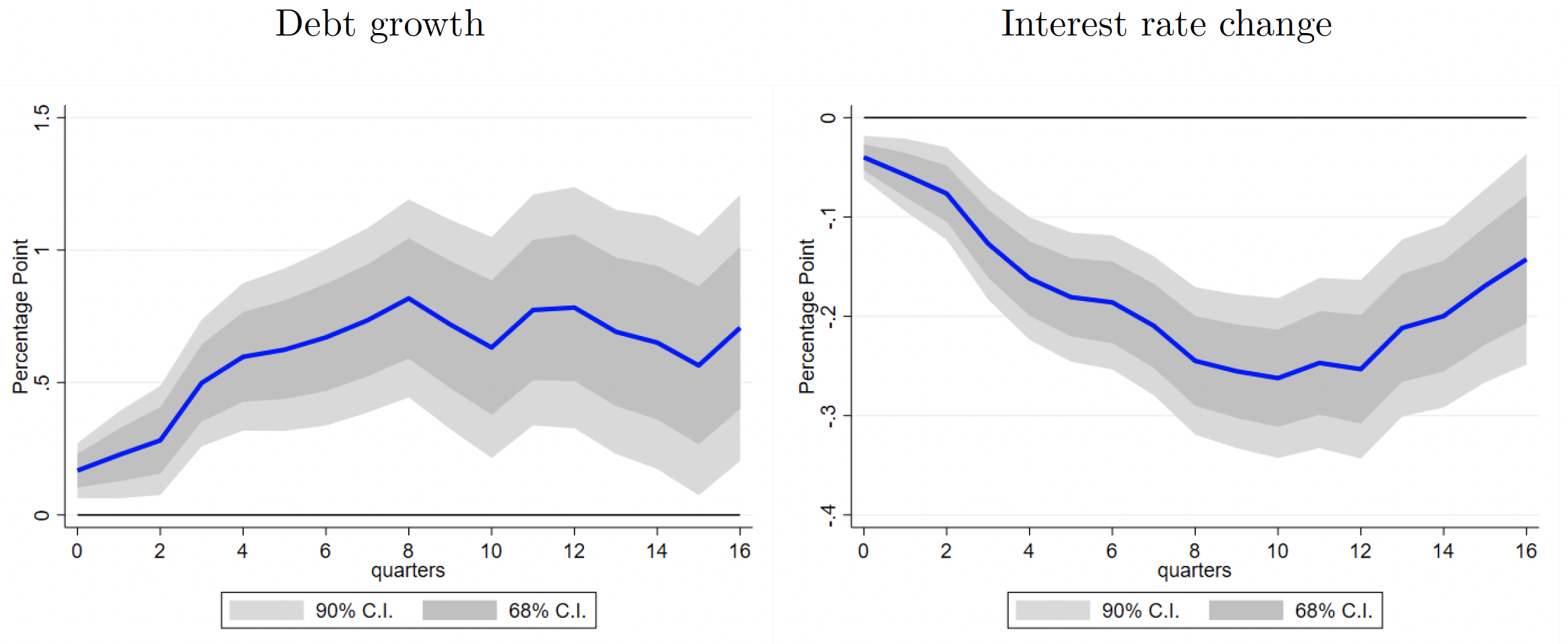

Figure 2 sheds some more light on this apparent counterintuitive result that zombie firms’ financial performance is less affected by interest rates increases. Credit standards tighten by less for zombie firms than other firms following a monetary policy shock: debt growth falls by less for zombie firms, of over 0.6 percentage points, while the cost of debt rises by less, by roughly 0.25 percentage points relative to non-zombies. Overall, the fact that zombie firms get more favourable credit conditions when financial conditions tighten provides supporting evidence for the conjecture that lenders engage in evergreening practices by shifting lending to zombies – the zombie lending channel of monetary policy. Against this background, we interpret this as evidence that zombie firms are less responsive to monetary policy because of lenders’ zombie lending.

Figure 2 Differential effect of monetary policy shocks on zombies versus non-zombies: Credit conditions

Notes: Cumulative impulse responses for zombie firms relative to non-zombies to a monetary policy shock that increases the country-specific one-year sovereign bond yields by 100 bps. The blue line is the average point estimate, and the dark (light) grey area refers to the 68% (90%) confidence bands.

In the paper, we further rationalise our empirical findings by drawing on a recent theoretical model from Faria-e-Castro et al. (2023), who show that lenders have incentives for evergreening loans by offering better terms to firms that are close to default. In this model, we show that when interest rates increase, lenders have further incentives to offer better credit conditions to zombie firms relative to other firms to prevent them from defaulting. Furthermore, banks may gamble for zombie firms’ resurrection, hoping that they recover or get market financing in the future, as zombies’ reputation grows with the length of their lending relationship (Hu and Varas 2021).

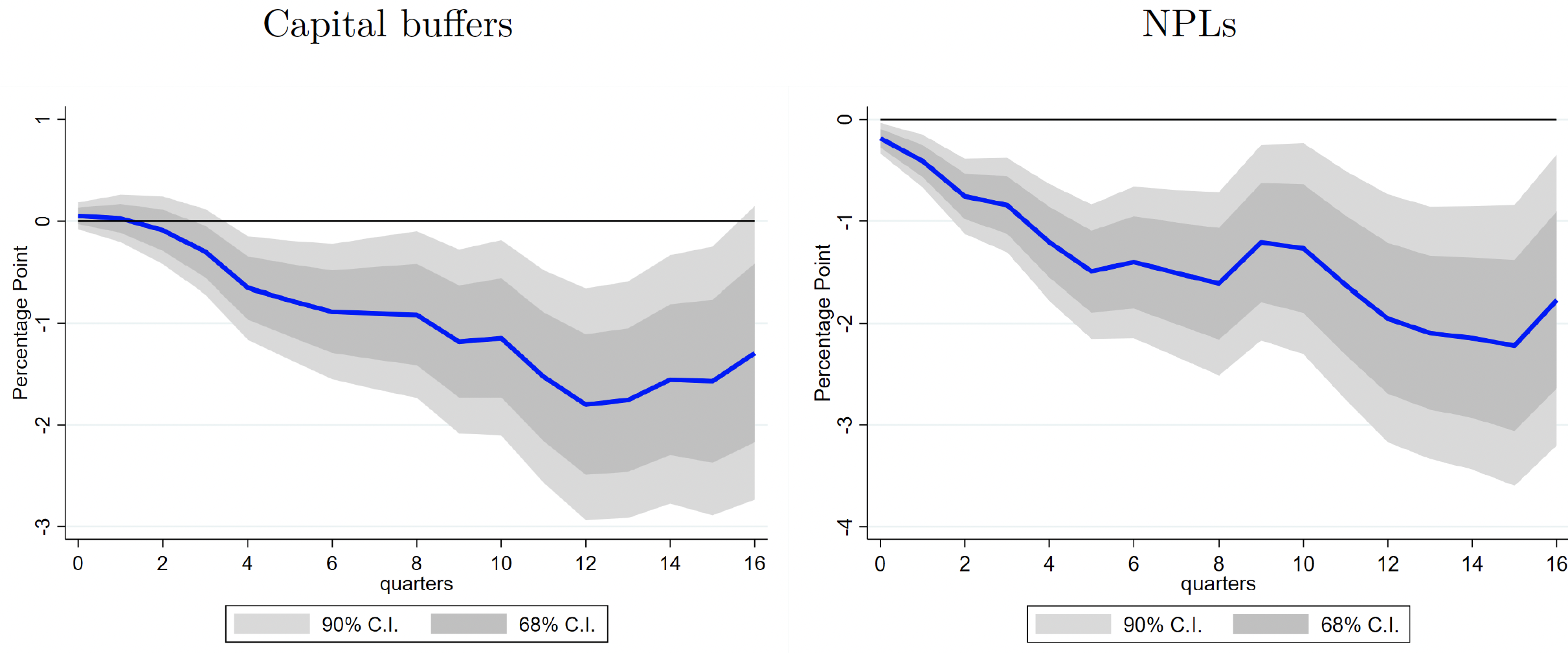

While the theoretical predictions of the model point to zombie lending taking place irrespective of concerns about bank capital, the model also predicts that evergreening motives are stronger for weakly capitalised banks – who may have less room to absorb the losses in case a zombie firm defaults. We investigate this empirically by studying the role that banks’ financial health may have in mitigating the differential effect of zombies’ financial performance relative to non-zombies following an increase in borrowing costs. We find that zombies’ financial performance in countries with higher regulatory capital buffers or lower nonperforming loans (NPLs) tend to experience a decline in investment growth relative to non-zombies following a tightening in monetary policy (Figure 3). This is suggestive evidence in line with our theoretical underpinning that highly capitalised banks are more bound to writing off zombie loans and absorb the losses.

Figure 3 Effect of contractionary monetary policy shocks on investment growth of zombies versus non-zombies: marginal effects in countries with stronger bank indicators

Notes: Cumulative marginal effects on investment growth of a monetary policy shock that increases the country-specific one-year sovereign bond yields by 100 bps. The blue line is the average point estimate for zombies versus non-zombies in countries that stand above (below) the median sample of the banks’ regulatory capital buffer (NPLs). The dark (light) grey area refers to the 68 (90) percent confidence bands.

Discussion

The world economy has seen a substantial tightening in monetary policy since 2022 to rein in inflation. In this column, we have argued that banks’ evergreening motive hinders the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission to zombie firms, potentially amplifying the adverse effects of monetary policy tightening on healthy corporates. This calls for policies that strengthen banks’ balance sheets, that limit banks’ incentives to engage in risky behaviour, including via stronger prudential supervision, and laws that allow an efficient resolution of weak firms.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column represent only our own and should therefore not be reported as representing the views of the International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

References

Acharya, V V, T Eisert, C Eufinger, and C Hirsch (2019), “Whatever It Takes: The Real Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy”, Review of Financial Studies 32(9): 3366–3411.

Albuquerque, B and R Iyer (2023), “The Rise of the Walking Dead: Zombie Firms Around the World”, VoxEU.org, 28 August.

Albuquerque, B and C Mao (2023), “The Zombie Lending Channel of Monetary Policy”, IMF Working Papers 23/192, International Monetary Fund.

Bahaj, S, A Foulis, G Pinter and P Surico (2022), “Employment and the residential collateral channel of monetary policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics 131: 26–44.

Banerjee, R and B. Hofmann (2022), “Corporate zombies: anatomy and life cycle”, Economic Policy 37(112): 757–803.

Becker, B and V Ivashina (2014), “Cyclicality of credit supply: Firm level evidence”, Journal of Monetary Economics 62(C): 76–93.

Berlin, M and L J Mester (1992), “Debt covenants and renegotiation”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 2(2): 95–133.

Bernanke, B S and M Gertler (1995), “Inside the Black Box: The Credit Channel of Monetary Policy Transmission”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 9(4): 27–48.

Borio, C.and H Zhu (2012), “Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: a missing link in the transmission mechanism?”, Journal of Financial Stability 8(4): 236–251.

Bruno, V and H S Shin (2015), “Capital flows and the risk-taking channel of monetary policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics 71: 119–132.

Caballero, R J, T Hoshi, and A K Kashyap (2008), “Zombie Lending and Depressed Restructuring in Japan”, American Economic Review 98(5): 1943–77.

Cloyne, J, C Ferreira, M Froemel and P Surico (2023), “Monetary policy, corporate finance and investment”, Journal of the European Economic Association, forthcoming.

Darmouni, O, O Giesecke and A Rodnyansky (2020), “Credit during a crisis: The bond lending channel of monetary policy”, VoxEU.org, 20 May.

Faria-e-Castro, M, P Paul, and J M Sanchez (2023), “Evergreening”, Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming.

Favara, G, C Minoiu, and A Perez (2022), “Zombie Lending to U.S. firms”, available at SSRN.

Gertler, M and P Karadi (2015), “Monetary Policy Surprises, Credit Costs, and Economic Activity”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 7(1): 44–76.

Gürkaynak, R S, B Sack and E Swanson (2005), “Do Actions Speak Louder Than Words? The Response of Asset Prices to Monetary Policy Actions and Statements”, International Journal of Central Banking 1(1): 55–93.

Hadlock, C J and C M James (2002), “Do banks provide financial slack?”, The Journal of Finance 57(3): 1383–1419.

Hu, Y and F Varas (2021), “A Theory of Zombie Lending”, The Journal of Finance 76(4): 1813–1867.

Ippolito, F, A K Ozdagli and A and Perez-Orive (2016), “How the use of floating-rate loans changes the impact of monetary policy”, VoxEU.org, 2 February.

Kashyap, A and J Stein (2000), “What Do a Million Observations on Banks Say about the Transmission of Monetary Policy?”, American Economic Review 90(3): 407–428.

McGowan, M A, D Andrews, and V Millot (2018), “The walking dead? Zombie firms and productivity performance in OECD countries”, Economic Policy 33(96): 685–736.

Nakamura, E and J Steinsson (2018), “High Frequency Identification of Monetary Non-Neutrality: The Information Effect”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 3(133): 1283–1330.

Rey, H (2013), “Dilemma not trilemma: the global cycle and monetary policy independence”, Proceedings - Economic Policy Symposium - Jackson Hole.