The steam revolution gave humans the ability to concentrate and control previously inconceivable amounts of energy. Over 100 years, the steam revolution and the Industrial Revolution performed an intricate waltz that completely transformed our relationship with the environment in general, and distance in particular. This launched Phase 3, the stage most people would think of as globalisation.

For most of human existence, people could consume only goods that were produced within walking distance. All human societies were governed by this ‘dictatorship of distance’. Phase 3 started when the distance dictatorship was overthrown. Steam power made the coup possible. Using the correlation of traded goods prices, economists Kevin O’Rourke and Jeff Williamson date the start of globalisation to 1820. (There is a lively discussion of this date among academics, as summarised by this excellent piece in The Economist).

Phase 3 really was a big deal. If Phase 2 can be thought of as laying the foundations of human civilisation, then Phase 3 can be thought of as building the edifice that we now call the 'modern world'. A key aspect of this was the Great Divergence, as Kenneth Pomeranz argued in his book of the same name. Incomes across the world had been broadly similar at the beginning of Phase 3 but by the end of Phase 3, a few nations became very rich, but most stayed quite poor.

Globalisation was a key part of this narrative. Radical improvements in transportation technology produced today's global economy. It underpinned the shifting of national production patterns. International trade rocketed as nations started to do what they did best, and trade for the rest.

Europe industrialises and modern growth starts

Europe industrialised, ending millenniums of stagnating incomes. By providing much larger markets, globalisation fuelled the cycle of industrialisation, agglomeration, and innovation. Industrialisation spread, but only to a handful of nations including the US, Canada, Australia, and Japan.

Other nations outside of this charmed circle did start growing, but their growth was slower took off later. This is what produced the Great Divergence. Unlike today, the normal situation in Phase 3 was for rich countries to grow faster than poor countries.

In short, the steam revolution, like the agricultural revolution before it, triggered a phase transition. Steam displaced wind and animal power and then, in turn, steam was displaced or augmented by internal combustion, electric engines, and air cargo. These breakthroughs in transportation technology made it economical to consume goods that had been made far away. For the first time in history, consumption and production did not have to happen in close proximity, they could be unbundled (which is why I called this globalisation’s ‘first unbundling’ in my 2006 paper, “Globalisation: The Great Unbundling(s))”.

Mastery of distance created three interconnected phenomena – trade, agglomeration, and innovation – which eventually turned the world economic order on its head.

The core becomes the periphery, and the periphery the core

Phase 3 created most dramatic reversal of fortune that history has ever seen. The global 'South', the core of ancient civilisations in Asia and the Middle East, especially India and China – which had dominated the world economy since the emergence of agriculture – became the periphery. The Atlantic economies and Japan (the global 'North'), previously the periphery, became the core.

In detail, there were four outcomes:

- International trade costs fell and trade boomed.

- The North industrialised while the South deindustrialised.

- Urbanisation accelerated, especially in the North.

- Growth took off everywhere, but sooner and faster in the North than in the South.

There was a very uneven distribution of productive know-how. The innovations developed in the North stayed in the North, and drove Northern wages and living standards far beyond those of the South.

1. International trade costs fall and trade booms

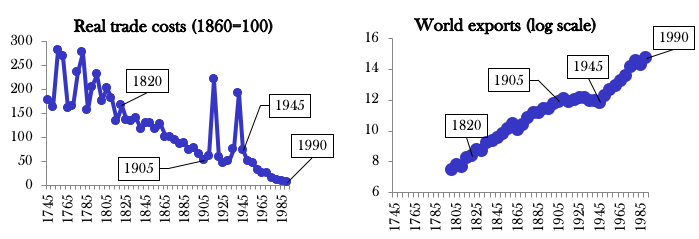

Trade costs (Figure 1, left panel), and trade volumes (right panel), both suggest Phase 3 falls into three sub-phases:

- Trade rose rapidly until WW1, spurred by the extraordinary reductions in barriers to trade that stemmed from the steam revolution and Pax Britannica, the period of relative peace following the Napoleonic Wars. Income growth was also a powerful stimulus to trade, so the Industrial Revolution in Europe, Japan, and the European offshoots like the US, Canada and Australia increased this trade bonanza.

- Trade stagnated between the world wars.

- Trade volumes continued their ascent after 1950.

Figure 1 International trade costs fell and trade boomed

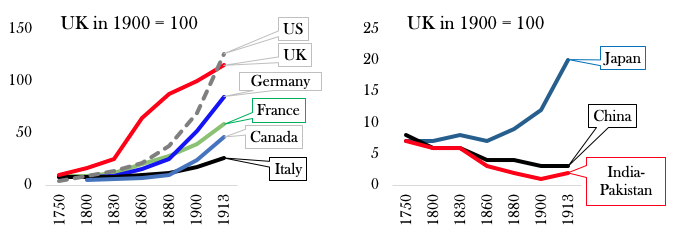

2. The North industrialises, China and India de-industrialise

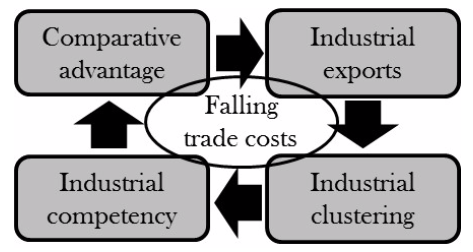

The Industrial Revolution started in the UK, and it spread to other North Atlantic economies. The result was a self-fuelling cycle of exporting, clustering and improved efficiency that boosted manufacturing in today’s rich nations (we can use today's shorthand and call them the G7: the US, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, Britain and Canada).

Figure 2 The cycle of exports, agglomeration, and industrial comparative advantage

Previously advanced nations in and around Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, and China found that their industry was undermined by the G7’s increased efficiency.

Figure 3 The G7 industrialises, China and India de-industrialise

3. Urbanisation accelerates

The first million-person city was, depending on who you believe, either Alexandria in Egypt or Baghdad in Iraq. Beijing and Nanjing followed. But this changed during Phase 3. At the end of Phase 3 there were around 16 cities with more than 1 million inhabitants. More than half of them were in the global North, in Europe and the US.

What is the connection between globalisation and urbanisation? There is today, and always has been, a strong correlation between urbanisation and rising incomes. This is due to a local self-reinforcing cycle in which workers (who are also consumers) move to cities to be near jobs, and the firms offering the jobs move to cities to be near consumers. As Harvard professor Ed Glaeser puts it in his book, Triumph of the City, smart people gather in cities and make each other smarter. We can detect these forces driving urbanisation in almost every large city in the world today.

4. Great divergence

The most profound change to the global economy was the great divergence. Rapid industrialisation in today’s rich nations sparked modern growth with a virtuous cycle of clustering, innovation and rising incomes. Growth in today’s poor nations took off later, and they grew more slowly than advanced nations for the next two centuries.

The result was that a historically unprecedented difference appeared between per-person incomes in the global North and South.

Globalisation as a three-act drama

The historical narrative for globalisation can, like Phase 2, be usefully broken up into three 'acts' (that line up with the three sub-phases of trade growth mentioned). Think of the Phase 3 as Globalisation: The movie.

- Act 1: Set-up. We meet our hero (Trade) and the other main characters (Industrialisation, Urbanisation and Growth). Things are going well. Lower costs! Railroads and steam ships! Act 1 lasts from 1820 to 1913.

- Act 2: Confrontation. The hero is tested. Daunting setbacks span two world wars and the Great Depression. Audiences gasp as events (Protectionism! Conflict!) force a re-bundling of production and consumption. Is our hero doomed? Act 2 lasts from 1914 to 1945.

- Act 3: Resolution. A happy ending is essential to a Hollywood movie and this movie was no exception. After WW2, costs are reduced by liberalisation and innovations in transport technology. Our hero (Trade) recovers strength and triumphs over Protectionism. Containers! Air cargo! Lower tariffs in rich nations! Act 3 takes us from 1950 to 1990.

Or, we can rewrite this movie (perhaps less snappily) as Long-run Reversal of Fortune: Global GDP.

- Act 1. GDP shares suddenly shift away from China, India, Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Egypt and Mexico (call them the A7) and towards the G7.

- Act 2. Stagnation.

- Act 3. This trend restarts.

Note that throughout this story, the sum of A7 plus G7 is approximately 80% of global GDP.

But note also that our movie ends in 1990. There is a sequel. The final part of this series looks at the New Globalisation – the one that’s been causing such great pains in the Global North, and such great gains in the Global South. As is often the case, the Hollywood sequel to this movie starts with disaster for the hero. In 2018, we do not yet know whether the sequel has a happy ending, or will turn out to be some French film noir.

References

Findlay, R and O'Rourke, K (2009) Power and Plenty, Princeton University Press.

Pomeranz, K (2000), The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy, Princeton University Press.