Nearly half of all families with infants in the United States receive the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). WIC differs from many other nutritional programmes due to its emphasis on healthful foods. The programme provides vouchers for specific foods that are high in nutrients such as iron, calcium, and potassium. In addition, the programme is only available to pregnant, post-partum, or nursing persons; infants; and children younger than five. Recipients must live in households with incomes less than 185% of the federal poverty guideline (approximately $28,000 for a family of four in 2022). Importantly, after a child turns five, the child is no longer eligible for the programme and they lose their full WIC bundle regardless of household income.

WIC is similar to many in-kind (non-cash) programmes like school meals and Medicaid in that it targets a specific person in a household. These programmes could nonetheless affect other household members by freeing up resources or by supplying goods that could be consumed by others. Most studies that examine the potential spillover effects of social safety net programmes focus on benefits that target parents but also help children; less is known about how programmes that target children affect adults in the household. In a recent paper (Bitler et al. 2022), we explore how having a child lose access to WIC affects the nutritional status and consumption of other household members.

Effects of WIC on household nutrition

Prior research has found that receiving WIC during pregnancy improves birth outcomes (see reviews by Currie 2003, Hoynes and Schanzenbach 2015, Caulfield et al. 2022). Much of this work leverages changes in access to WIC from the programme’s introduction or clinic closures (Hoynes et al. 2011, Rossin-Slater 2013) as well as sibling comparisons (Kowaleski-Jones and Duncan 2002, Chatterji et al. 2002, Currie and Rajani 2015, Foster et al. 2010). These studies use different methods than we do and generally find that WIC benefits very young children.

The impact of WIC on older children is less well understood, and there is very little evidence on how the programme affects other household members who are not the targeted beneficiaries. There is a small body of work leveraging the age-five cut-off that finds mixed results. While some find increases in household food insecurity as children turn five (Arteaga et al. 2016) and increased food bank use at the same point (Si and Leonard 2020), others find that the effect of aging out on food hardship is limited to children likely not in school (Smith and Valizadeh 2022).

Our article builds on the existing literature by examining how the loss of WIC for children impacts other household members. Specifically, we ask if mothers insure children’s nutrition by reducing their own food consumption. We address this question by combining information on the children’s exact dates of birth with information about the consumption of other household members from a nationally representative study covering 25 years. Specifically, the restricted-use National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) data we use includes detailed food diaries and biomarkers from laboratory tests that provide objective measures of nutrition and diet quality.

We compare consumption and food insecurity for low-income families in the days before the end of the month in which a child turns five (and is therefore likely still eligible for WIC) to those with children just above that age cut-off (who are ineligible for WIC) using a regression discontinuity approach.

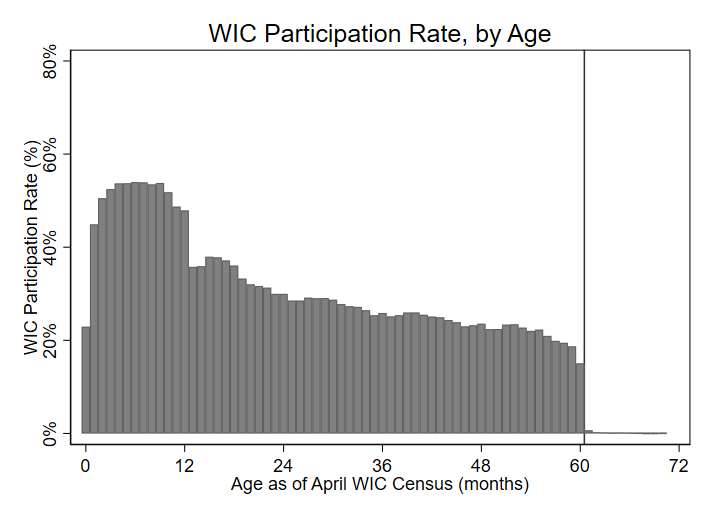

We first document that the end of the month when a child turns five coincides with a sharp decrease in WIC participation using administrative data.

Figure 1 WIC participation rate by age in months

Notes: The figure displays the fraction of children at each age who are enrolled in WIC, with the numerator coming from WIC administrative Program Characteristics data from 1996 to 2016 for even years and the denominator coming from Vital Statistics data on births of that age in months.

Second, we find that the loss of WIC benefits has little effect on children as they age out of the programme. That is, children do not change their milk consumption (a key WIC package ingredient) or overall calories consumed, and blood tests show no increases in anaemia, or decreases in haematocrit or haemoglobin.

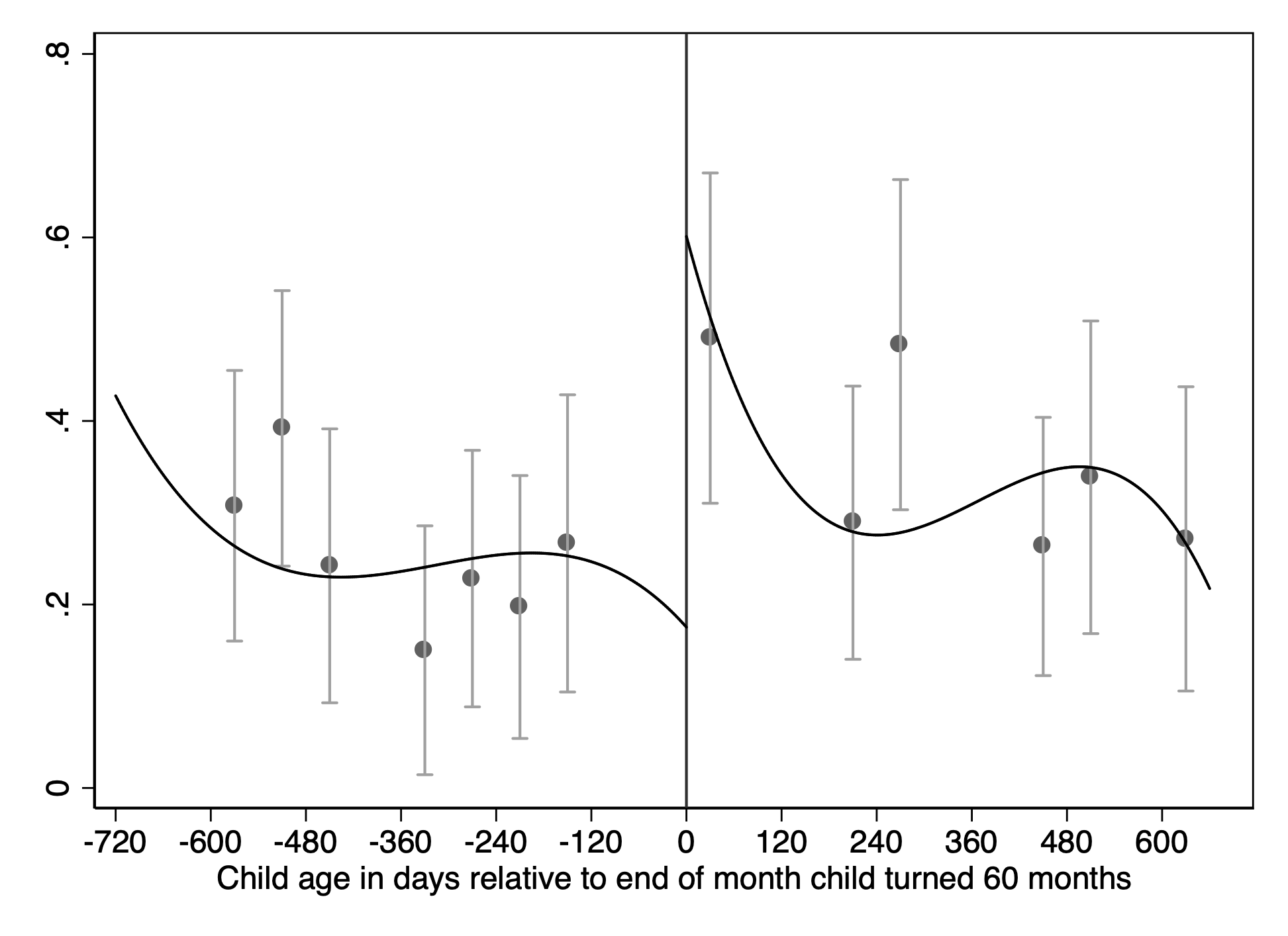

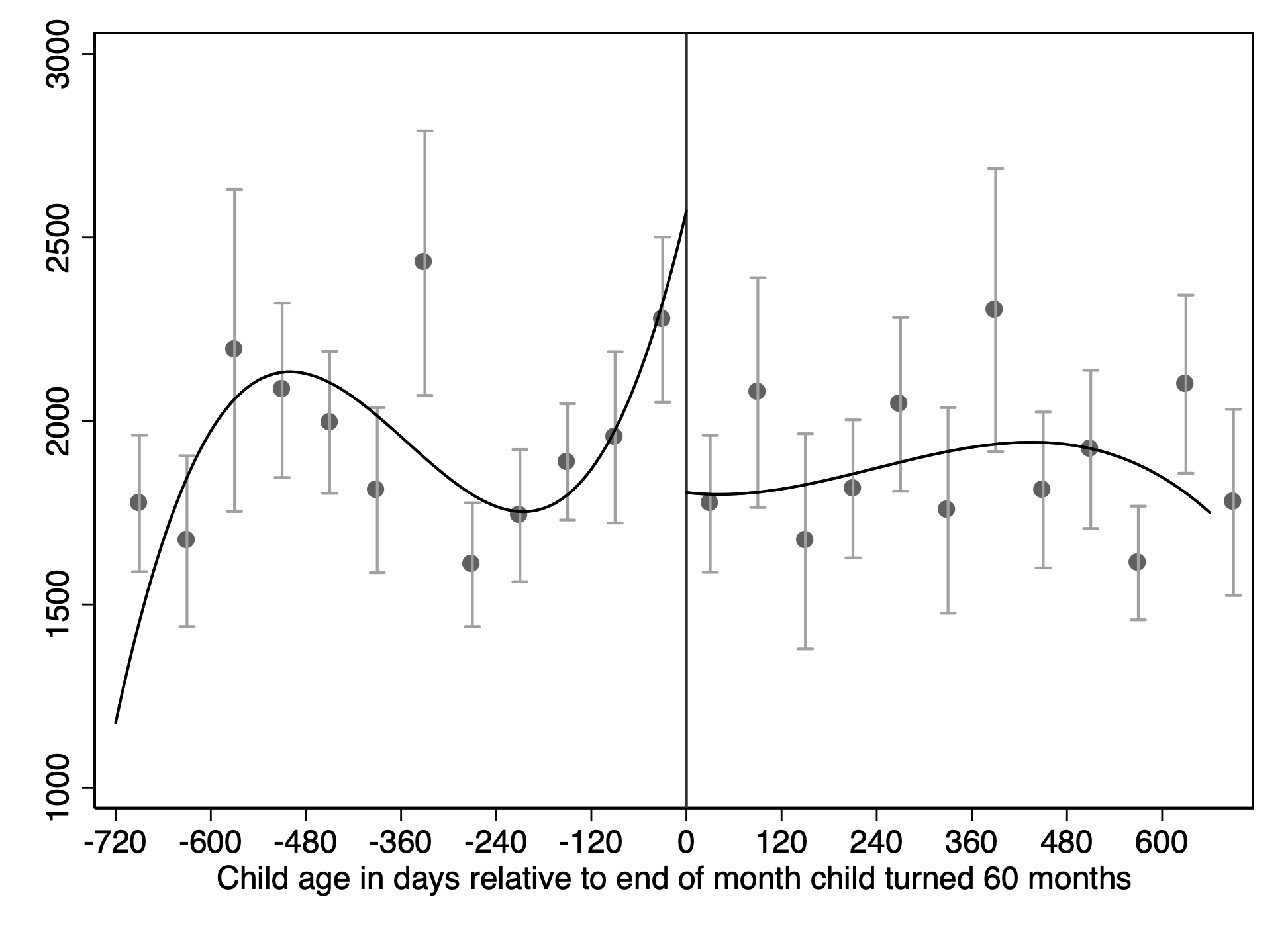

Even though losing access to WIC does not substantially change children’s food intakes, women in these households buffer children against nutritional loss by consuming fewer calories themselves, even as the overall healthfulness of their diets does not change. Altogether, measures of food insecurity, which indicate the adequacy and affordability of food, do not change for children when a child ages out of the programme, but increase for adults in the same households.

Figure 2 Effect of household member losing WIC benefits on adult women

a) Moderate food insecurity

b) Calories

Notes: Each figure provides a visual representation of a regression measuring the effect of losing WIC benefits. Each dot on the figure represents the weighted mean of the outcome variable listed in the title, for adult women ages 20-50 living with children in that 60-day bin, and the bars give the 95% confidence interval for the mean. The model, and the fitted line, come from a cubic regression specification. The distance between the fitted lines on each side of 0 gives the effect of aging out of WIC. Any cell with fewer than 30 observations or with no variation is suppressed from the graphs. These disclosure restrictions do not affect the fitted polynomial line. Limited to families living at less than 200 percent of the FPL with one child between the ages of 3 and 7. The bandwidth is 719 days, and the estimates use a triangular kernel. Calories averaged over two days of food diary when available.

Implications for nutrition assistance policy

These findings show that the loss of public programme benefits targeted to particular individuals can spillover to harm others in the household. Specifically, we find that even if the loss of WIC does not directly harm children, mothers are harmed by buffering children’s nutrition consumption.

Our findings are identified by children who remained on WIC until their fifth birthdays. As these children are likely to have younger siblings and particularly low levels of family income (Chorniy et al. 2019), our findings may reflect the impact of WIC in the largest and highest need families. This group is an important population to study, given disproportionately high rates of food insecurity, worse nutrition, and a higher probability of food-related illness among low-income families.

Finally, while we study the effect of families losing nutritional assistance, one might expect these patterns to be symmetric. We might see benefits from programme expansions. Indeed, one comparably sized expansion arose with a demonstration project that provided a monthly grocery voucher of $60 to families with children during the summer. This demonstration reduced adult food insecurity from 50% to 41%, a reduction of 18.5% (Collins et al. 2016), which is consistent with our findings-gaining benefits led to less food insecurity. Policymakers contemplating new programmes or reforms to existing programmes should consider the full range of costs and benefits – both to targeted individuals and in terms of spillovers onto other family members.

Authors’ note: This research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Evidence for Action Program (grant #75116). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Foundation.

References

Arteaga, I, C Heflin, and S Gable (2016), "The impact of aging out of WIC on food security in households with children", Children and Youth Services Review 69: 82-96.

Bitler, M P and J Currie (2005), "Does WIC work? The effects of WIC on pregnancy and birth outcomes”, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 24(1): 73-91.

Bitler, M, J Currie, H W Hoynes, K J Ruffini, L Schulkind and B Willage (2022), "Mothers as Insurance: Family Spillovers in WIC", NBER Working Paper 30112.

Caulfield L, W Bennett, S Gross et al. (2022), “Maternal and Child Outcomes Associated With the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC),” Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 253, AHRQ Publication No. 22-EHC019.

Chatterji, P, K Bonuck, S Dhawan, and N Deb (2002), WIC Participation and the Initiation and Duration of Breastfeeding, Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Cho, S (2022), "The effect of aging out of the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program on food insecurity”, Health Economics 31(4): 664-685.

Chorniy, A, J Currie, and L Sonchak (2020), "Does prenatal WIC participation improve child outcomes?", American Journal of Health Economics 6(2): 169-198.

Collins, A, R Briefel, J Klerman et al. (2016), “Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children Demonstration: Summary Report”, USDA Dept. of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service.

Currie, J (2003), “U.S. Food and Nutrition Programs,” in R Moffitt (ed.), Means- Tested Transfer Programs in the United States, University of Chicago Press for NBER, 199–290.

Currie, J and I Rajani (2015), "Within‐Mother Estimates of the Effects of WIC on Birth Outcomes in New York City”, Economic Inquiry 53(4): 1691-1701.

Foster, E M, M Jiang, and C M Gibson‐Davis (2010), "The effect of the WIC program on the health of newborns”, Health Services Research 45(4): 1083-1104.

Hoynes, H, M Page, and A H Stevens (2011), "Can targeted transfers improve birth outcomes?: Evidence from the introduction of the WIC program”, Journal of Public Economics 95(7-8): 813-827.

Hoynes, H and D Schanzenbach (2015), “U.S. Food and Nutrition Programs”, in R Moffitt (ed.), The Economics of Means Tested Programs in the US, Volume I. University of Chicago Press.

Kowaleski-Jones, L and G Duncan (2002), "Effects of participation in the WIC program on birthweight: evidence from the national longitudinal survey of youth”, American Journal of Public Health 92(5): 799-804.

Rossin-Slater, M (2013), "WIC in your neighborhood: New evidence on the impacts of geographic access to clinics”, Journal of Public Economics 102: 51-69.

Schanzenbach, D W (2009), "Do school lunches contribute to childhood obesity?", Journal of Human Resources 44(3): 684-709.

Si, X, and T Leonard (2020), "Aging out of Women Infants and Children: An investigation of the compensation effect of private nutrition assistance programs”, Economic Inquiry 58(1): 446-461.

Smith, T and P Valizadeh (2022), “Aging out of WIC and Child Nutrition: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design”, Working paper.