Inflation has become a concern for policymakers worldwide. Its potential causes include geopolitical tensions, supply chain disruptions, expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, and rising commodity prices (Ilzetzki 2022). This has also been an issue in the UK, which has experienced higher inflation than other G-7 economies, and raised the question of whether and how Brexit has contributed to rising prices.

There are different channels through which Brexit can affect price levels. One source is the pound devaluation, as Breinlich et al. (2022) find. Our research highlights an alternative source: the trade policy uncertainty (TPU) associated with Brexit. Specifically, we find that uncertainty about the future trading conditions with the EU increased the UK's import prices from the EU-27, with the leave referendum raising those prices by as much as 10%.

Referendums, export investments, and Brexit uncertainty

The opportunity to vote for Brexit in the 2016 referendum increased uncertainty about the future trade conditions between the EU and the UK. In 2013, the UK Prime Minister David Cameron raised the possibility of a referendum on the EU and announced he would follow through after the Conservative election victory in May 2015. As the June 2016 referendum approached, 83% of UK Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) reported high uncertainty, as did CFOs in Ireland (55%), the Netherlands (69%), and Germany (93%) (Deloitte 2016). UK CFOs ranked the Brexit referendum as the number one risk to their business over the next 12 months in 2016Q1. Similarly, two-fifths of CFOs in Europe ranked geopolitical risks as the first or second most important risk factor.

With the UK's membership status in danger, firms in other EU countries had to make investment decisions without knowing whether they would continue to have duty-free market access. Export investments include setting up distribution networks, acquiring consumers, matching quality to foreign tastes and product standards to regulations, as well as learning customs procedures. These investments in export capital cannot be easily recovered when market conditions worsen, for example if tariffs or other trade barriers increase.

Since at least May 2015, an EU firm had to consider the possibility that the UK would vote for Brexit, and a new agreement had to be renegotiated. If no deal could be reached, import tariffs on EU goods could increase by as much as 15 percentage points on some products, enough to significantly reduce expected future sales to UK customers. In Graziano et al. (2021), we use the difference between duty-free rates on EU trade and the Most Favoured Nation tariffs (MFN) to measure tariff risk from Brexit. We find that increases in the probability of Brexit reduce EU-UK trade in goods, particularly in industries with higher potential MFN tariff rates, such as motor vehicles.

Brexit uncertainty, UK import prices, and inflation

There is a substantial amount of evidence showing that trade agreements increase trade by reducing trade policy uncertainty (Handley and Limāo 2022). Brexit provides evidence of the same phenomenon in reverse: trade reduction due to a disagreement. However, much less is known about the price effects of trade policy uncertainty, and this is the focus of Graziano et al. (2023).

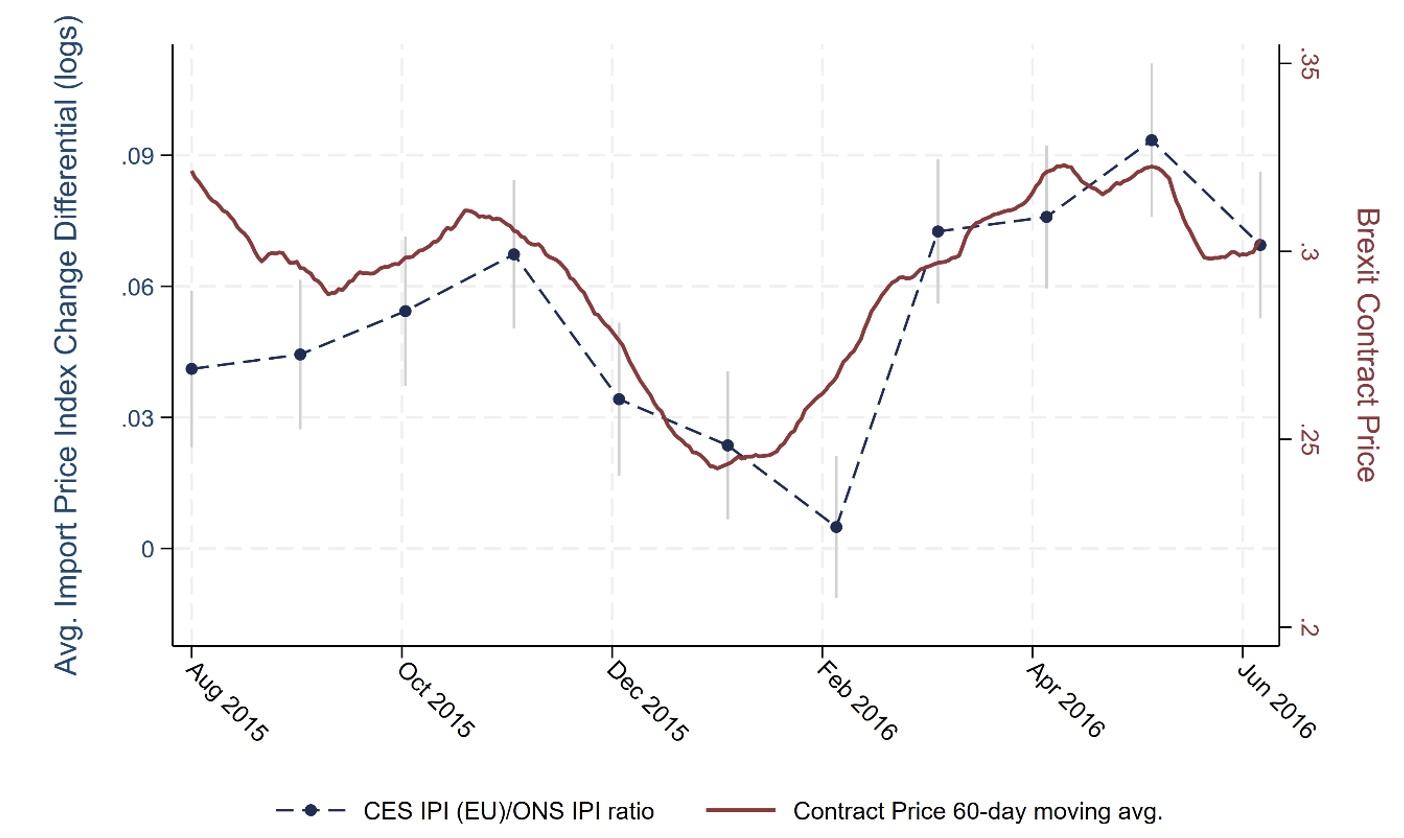

We first examine how the Brexit probability before the referendum is correlated with the growth in the UK import price index of goods imported from the EU versus its total imports. We use prediction markets on the referendum outcome to capture the likelihood of Brexit. To measure relative prices, we construct monthly import price indices from each EU exporter to the UK for each of the 1200 industry groups (e.g. babies' garments and clothing accessories from France), capturing 12-month changes. We plot its average relative to the UK aggregate import price index from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), which captures 12-month price changes in imports from all countries. As shown in Figure 1, the relative price of EU imports comoves closely with the Brexit probability measure.

Figure 1 Relative EU import price change and Brexit probability

Source: Graziano et al. (2023)

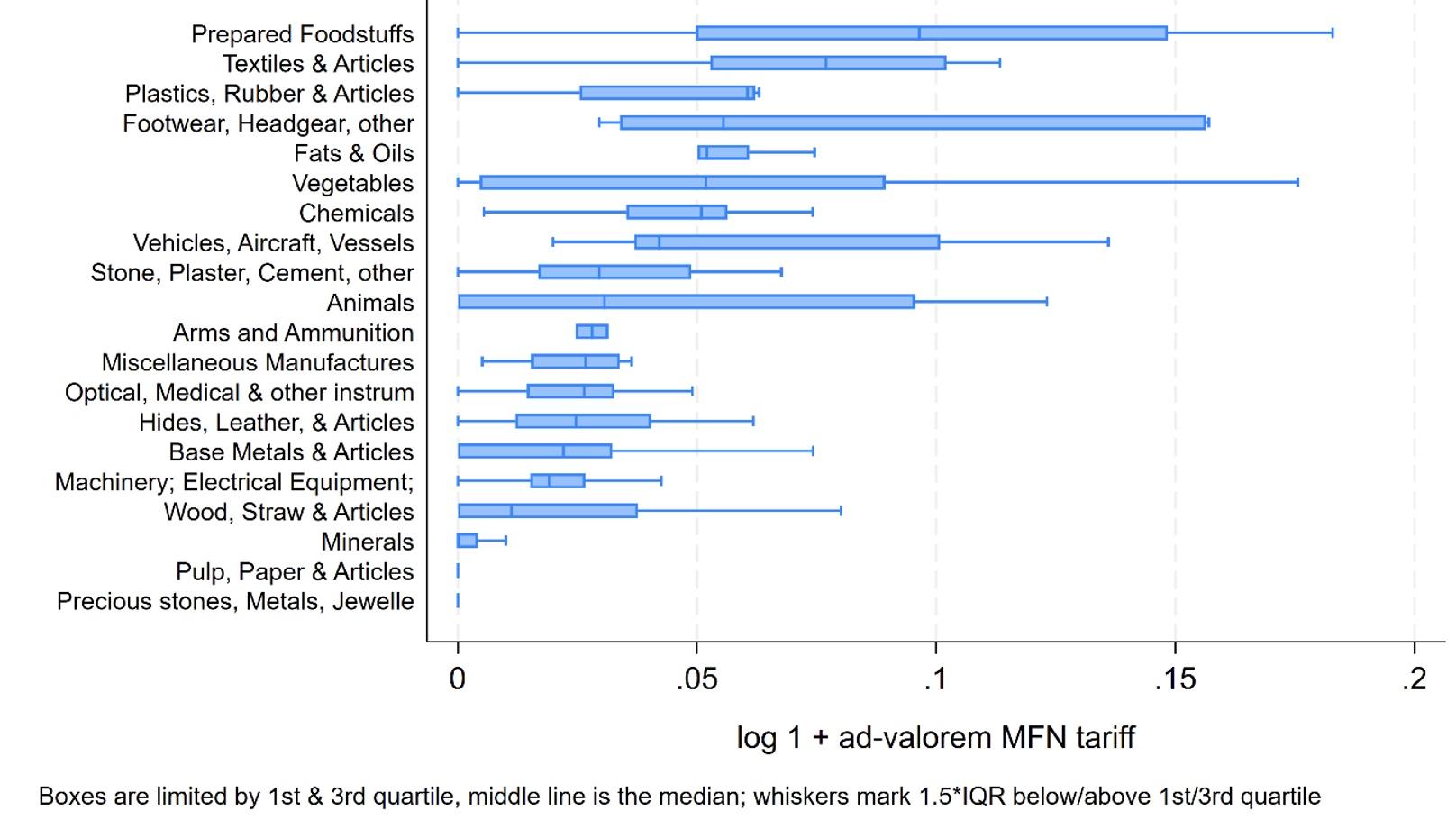

EU firms would have expected UK tariffs to be higher on some goods after Brexit. In Figure 2, we show the sector-specific Most Favoured Nation tariff distribution imposed on different products by the EU—the reference we use for likely future UK tariffs. The threat of facing higher protection was heterogeneous between and within sectors. For instance, in “Vehicles, Aircraft, Vessels,” the increase would be 9% for motor vehicles but only 2% for trailers. In contrast, no products in "Pulp, Paper & Articles" would face a Most Favoured Nation tariff threat.

Figure 2 Sector-specific distribution of potential Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariff rates

Source: Authors calculations using data from Graziano et al. (2023).

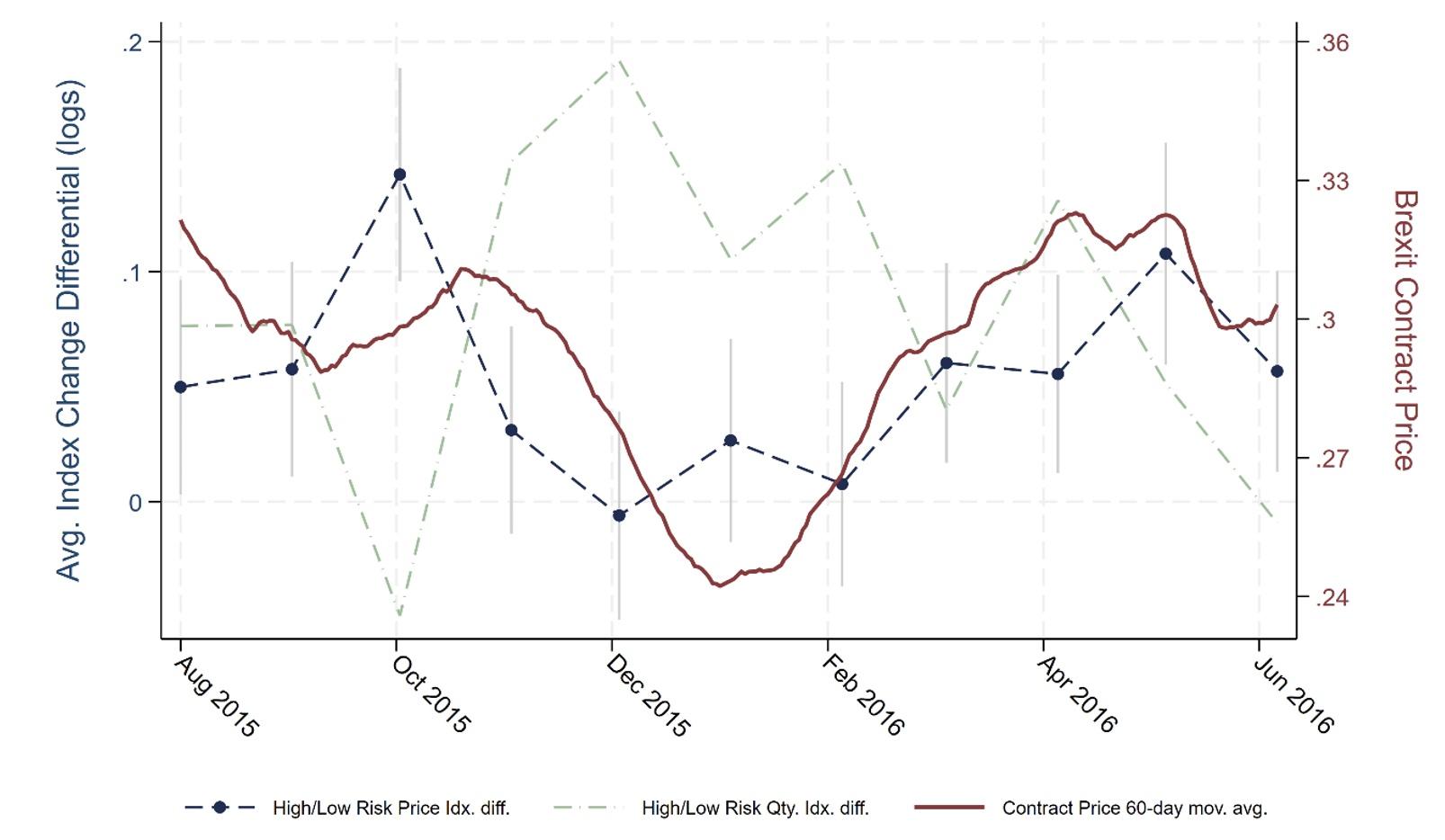

The theory predicts a stronger relationship between import price changes and the Brexit referendum probability for those products with higher Most Favoured Nation tariff risk. This is what we find in Figure 3: the relative price change of high to low-risk goods comoves with the Brexit probability.

Figure 3 Relative price and quantity changes and Brexit probability

Source: Graziano et al. (2023)

Figure 3 also shows a negative relationship between relative import quantities in high to low-risk goods and the Brexit probability. The increase in price and decrease in quantities implies a supply rather than a demand shock, ruling out alternative channels such as stockpiling high-risk goods.

The descriptive evidence above is consistent with a trade policy uncertainty channel for increasing UK import prices. Yet, it does not rule out certain alternatives or allow for easy quantification. Therefore, we derive and estimate the impact of pre-referendum trade policy uncertainty on import prices by exploiting the different Most Favoured Nation tariffs these goods could face and the changes in the probability of Brexit over time. In effect, the estimation answers if import prices of specific items, e.g. baby garments from France, were systematically higher in months when the Brexit outcome was more likely when compared to price changes of hats and other headgear from France, which would face lower tariffs.

We find that trade policy uncertainty increased import price indices. A one standard deviation increase in the pre-referendum probability of Brexit increased import prices by 2% at the average Most Favoured Nation tariff. This effect is due to increases in prices of products continuously traded throughout the year and a decrease in the available varieties.

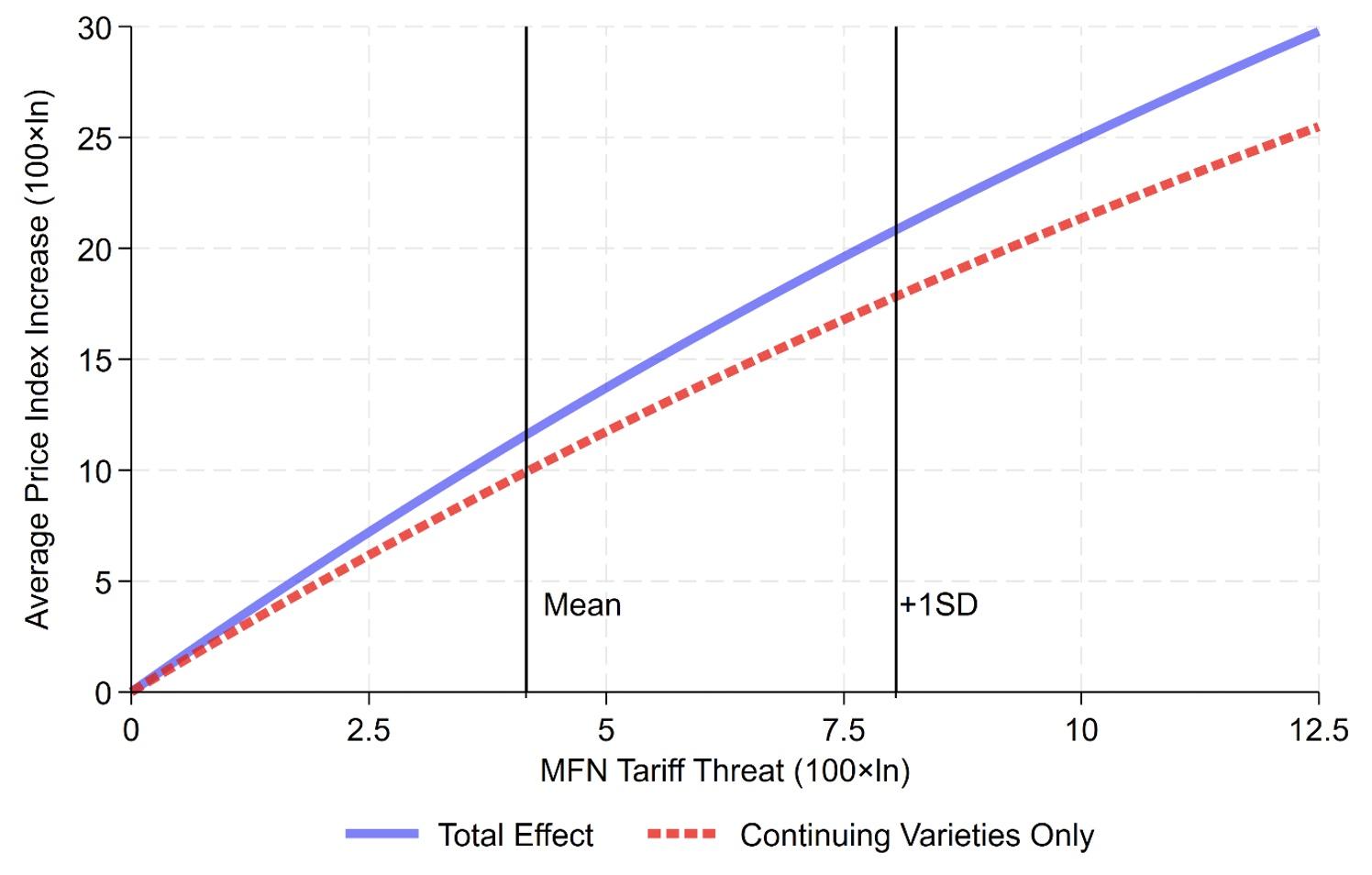

Using the model and our estimates, we quantify the impact of the referendum outcome on UK import prices. Figure 4 plots the average price impact under alternative Brexit tariff threats. Our preferred estimate implies that the increase in probability after the referendum increased UK import price indices for EU goods by around 11%.

Figure 4 Predicted post-referendum price impacts across tariff risk factors

Source: Graziano et al. (2023)

Consumer price effects and policy implications in the age of high inflation

About 7% of total UK expenditure was on EU imports in our sample. Therefore, an 11% increase in the price of EU imports significantly impacts UK consumers and firms. Our calculations indicate that the prices for UK households and consumers increased by 0.6% due to higher trade policy uncertainty generated by the Brexit referendum outcome. This trade policy uncertainty remained in place and likely grew at least until an agreement was reached years later.

The Trade and Cooperation Agreement reduced some of the trade policy uncertainty present in 2015-2020, but has not eliminated it. For example, changes to rules of origin have meant some EU firms face Most Favoured Nation tariff rates.

Likewise, the status of the sea border in Northern Ireland and the potential for renegotiation of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement remain a source of uncertainty.

Brexit provides a clear example of how reductions in the credibility of trade agreements can exacerbate price pressure on consumers even in the absence of applied policy changes.

References

Ahir, H, N Bloom and D Furceri (2022), “The world uncertainty index", NBER Working Paper 29763.

Breinlich, H, E Leromain, D Novy and T Sampson (2022), “The Brexit vote, inflation, and UK living standards”, International Economic Review 63(1): 63-93.

Deloitte (2016), “European CFO Survey: Politics takes centre stage”, May.

Graziano, A G, K Handley and N Limão (2021), “Brexit uncertainty and trade disintegration”, The Economic Journal 131(635): 1150-1185.

Graziano, A G, K Handley and N Limão (2023), “An Import (ant) Price of Brexit Uncertainty” NBER Working Paper 31600.

Handley, K and N Limão (2022), “Trade policy uncertainty”, Annual Review of Economics 14: 363-395.

Ilzetzki, E (2022), “Surging inflation in the UK”, VoxEU.org, 10 February.

UK Fashion & Textile Assoc (2021), "Brexit Bureaucracy Hits UK Fashion and Textile Companies Hard", July.