In recent years, the use of digital payment methods for transactions has been increasing at the expense of cash, a pattern that has become more pronounced since the outbreak of the Covid-19 crisis (e.g. Auer et al. 2020). In response to this shift, central banks have started to investigate the benefits and implications of issuing central bank digital currency (CBDC). The ultimate goal of a CBDC is to ensure that individuals operating in an increasingly digitalised economy continue to have access to public money as a means of payment.

However, there are concerns that if also widely used as a store of value, CBDCs may disintermediate banks (e.g. ECB 2020, Adalid et al. 2022, Bindseil and Panetta 2020, and Jamet et al. 2022). Given the perceived degree of substitutability between CBDC and bank deposits (Burlon et al. 2022) and the increasing demand for safe liquid assets as a store of value, there are good grounds for this concern.

The aim of our new study (Muñoz and Soons 2023) is to evaluate how the introduction of a CBDC as a store of value affects bank intermediation, investments and welfare by altering consumers’ portfolio choice between public money and private money in a model that accounts for the empirical evidence on cash holdings. For this purpose, we develop a model a la Diamond and Dybvig (1983) with public money and heterogeneous beliefs about bank stability. Our simulations show that there is a wide range of cases in which, despite the partial disintermediation of banks, the introduction of a CBDC that serves as a superior technology for storage of information increases social welfare.

Motivating evidence

Our analysis is motivated by three key empirical findings:

- The bulk of cash is held for store of value purposes. Despite the fact that the use of cash as a means of payment has been decreasing in recent years, cash holdings as a percentage of GDP have continued to increase (Ashworth and Goodhart 2020).

- Cash holdings sharply increase in times of high economic uncertainty. Various empirical studies document the heavy reliance of demand for cash on economic uncertainty, perceived bank stability and the state of the economy (e.g. Jobst and Stix 2017, Rosl and Seitz 2021, Baubeau et al. 2021).

- Only a proportion of the population holds cash as a store of value. For the particular case of the euro area, see ECB (2022) and Zamora-Perez (2021).

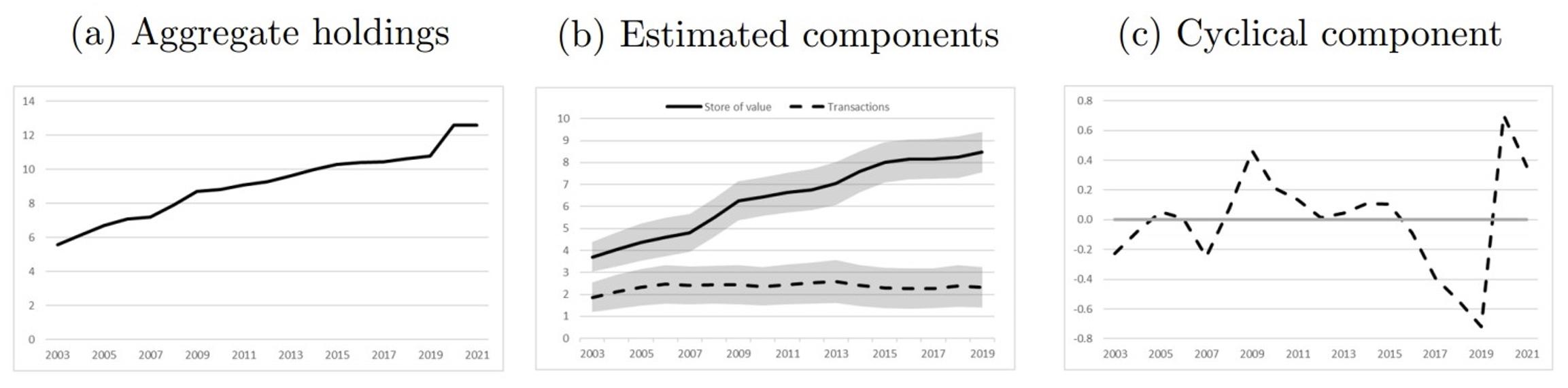

Figure 1 illustrates some of these empirical observations for the case of the euro area. Panel (a) reports euro-denominated aggregate cash holdings as a per cent of GDP at the annual frequency and for the period 2003-2021. Cash holdings have been increasing over the entire horizon. Panel (b) displays the estimated component of total cash holdings used for transaction purposes (dashed line) and that used as a store of value (solid line).

The steady increase in aggregate cash holdings over time is to be mainly attributed to the patterns of the estimated cash holdings as a store of value. Panel (c) plots the cyclical component of euro-denominated aggregate cash holdings.

Figure 1 Euro-denominated cash holdings

Source: Muñoz and Soons (2023).

Notes: Cash holdings are defined as the value of euro-denominated banknotes in net circulation as a per cent of GDP, at the annual frequency. Variables represented in panels (a) and (b) are expressed in percentage points. The one plotted in panel (c) is expressed in percentage deviations from the HP trend with a standard smoothing parameter of 100.

A Diamond and Dybvig model with cash as a store of value

Against this background, we develop a version of the Diamond and Dybvig canonical bank-run model augmented with cash, which we refer to as the baseline model. As in Cooper and Ross (1998) and Ennis and Keister (2006), the probability of the bank-run equilibrium is exogenously determined according to an equilibrium selection rule. Such exogenous probability captures bank stability and the state of the economy and is assumed to be public information. Importantly, we interpret the short-term asset in which banks invest as ‘reserves’ (i.e. digital public money that can only be directly accessed by banks). To capture the technological superiority of reserves when compared to cash (due to the digital nature of the former), we normalise to zero any storage costs the former might be subject to, whereas we assume that cash storage costs are strictly positive.

However, this simple extension of the Diamond and Dybvig model does not account for the above-described evidence on cash holdings. On the contrary, in this setup, there is no demand for cash in equilibrium, and it is, thus, not suited to study CBDC. Why? Because the bank can always offer a run-proof contract – by fully investing consumers’ endowment in reserves – that is preferred to cash. This preference is due to the digital nature of reserves. Thus, in the baseline model, there is no role for public money as a store of value, as consumers always prefer placing their endowment in a deposit contract, regardless of the (known) probability of a bank run. This finding follows from our assumption that, same as for the case of consumers, the central bank faces an adverse selection problem which impedes them from investing in long-term assets (i.e. lending). By making this empirically relevant assumption (i.e. asymmetric information faced by central banks and their related risk management frameworks), our analysis rules out the possibility of having a central bank deposit monopoly (Fernandez-Villaverde et al. 2020).

The role of heterogeneous beliefs about bank stability

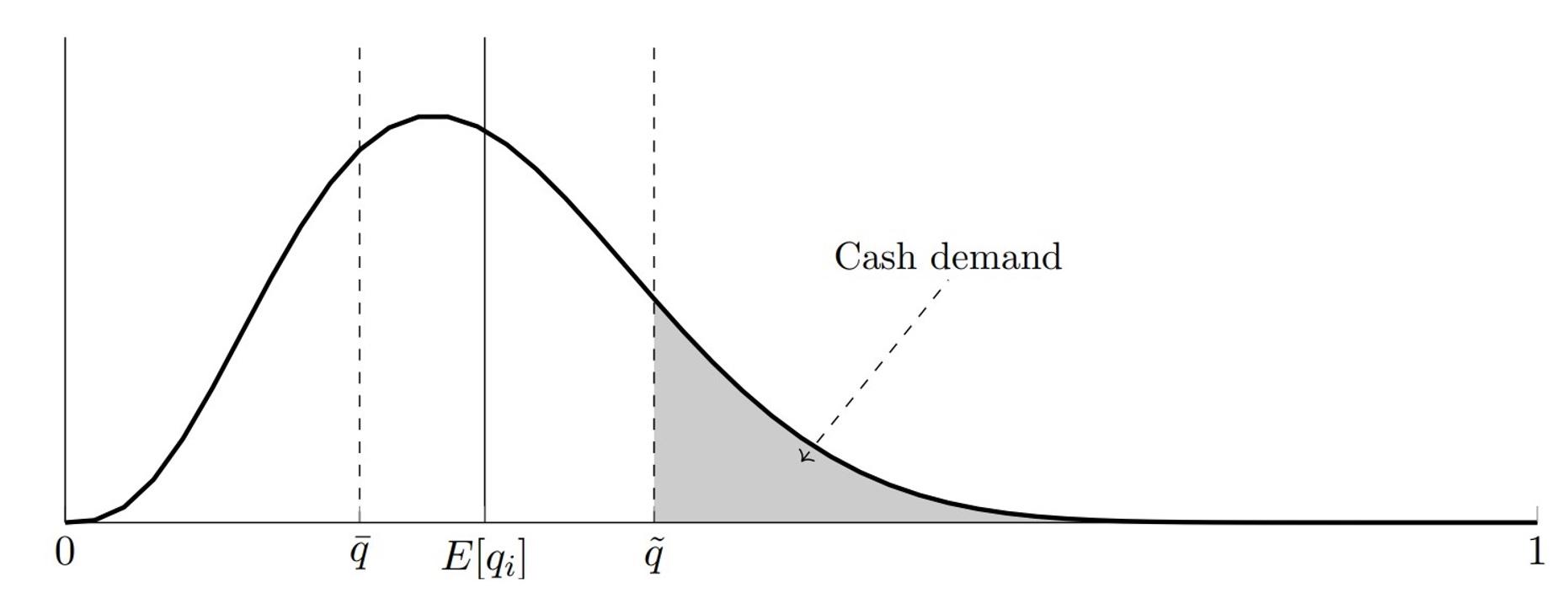

Consider an extension of the baseline model in which the exogenous probability of a bank run is no longer public information. In this environment, consumers have heterogeneous beliefs about such probability (i.e. about bank stability). We refer to this setup as The Model. Provided that the bank deposit contract is run-prone, we show that those consumers who are sufficiently pessimistic about bank stability opt for placing their endowment in cash rather than in bank deposits. The bank offers a single deposit contract to all depositors by maximising the expected utility of the average belief depositor. As illustrated in Figure 2, aggregate demand for cash as a store of value is given by the sum of all individual cash holdings by consumers whose individual beliefs are below a threshold. The fraction of the population that holds cash as a store of value is given by one minus this threshold.

Figure 2 Aggregate demand for cash

Source: Muñoz and Soons (2023).

Notes: The figure illustrates cash demand for a particular Beta distribution of beliefs.

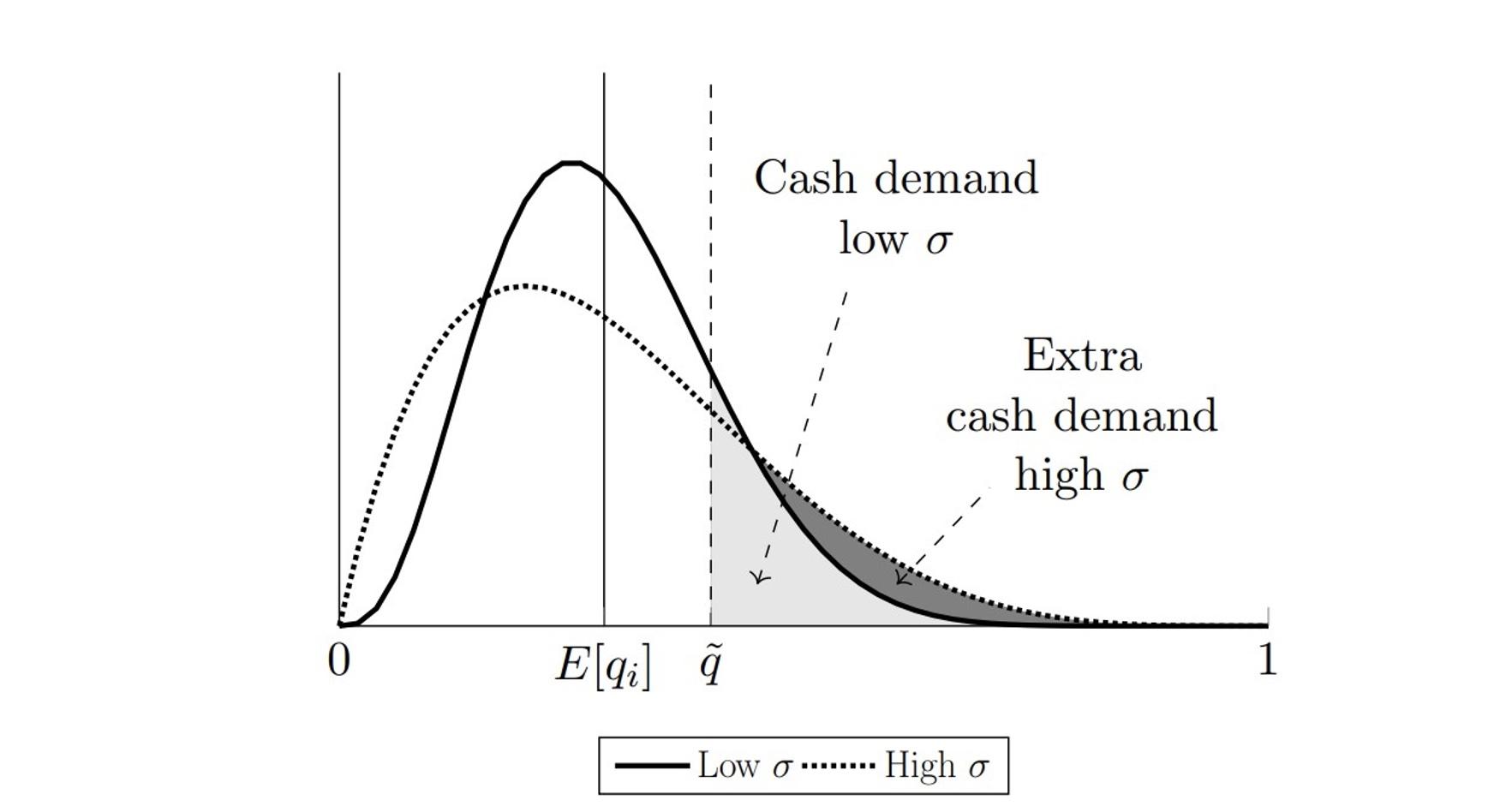

In The Model, the dispersion in individual beliefs captures aggregate economic uncertainty. We show that an exogenous increase in belief dispersion (i.e. increased disagreement) expands aggregate cash holdings as the mass of individuals in the tails of the distribution goes up (Figure 3). That is, The Model accounts for the above-outlined empirical facts.

Figure 3 Impact of uncertainty

Source: Muñoz and Soons (2023).

Notes: The figure illustrates cash demand under a Beta distribution of beliefs that assumes more or less belief dispersion.

CBDC as a superior technology for storage of information

Then, we introduce an unremunerated CBDC that is technologically superior to cash and in which consumers can directly place their endowments.

For simplicity, we assume that introducing CBDC affects neither the probability of a bank run nor individual beliefs about such probability.

In The Model, the issuance of CBDC reduces bank intermediation and productive investment by altering portfolio choices on the basis of individual beliefs about bank stability. CBDC lowers the storage cost of holding public money and, thus, expands the set of consumers who prefer to hold public money. All cash holders switch to CBDC, and some depositors also opt for switching to CBDC based on their beliefs. Interestingly, as the demand for public money increases, the average depositor is more optimistic about bank stability. Consequently, the bank optimally rebalances its portfolio towards a larger share of long-term lending as its depositor base is less concerned about its liquidation value in case of a bank run. Thus, while in absolute terms, the issuance of CBDC as a store of value leads to a decline in bank deposits and lending, in relative terms, it translates into increased maturity transformation.

We study the welfare implications of issuing CBDC as a store of value in The Model. Performing a welfare analysis in such a heterogeneous agents environment is challenging (Brunnermeier et al. 2014, Davila and Schaab 2022). Does individual welfare depend on the objective probability of a bank run or on subjective individual beliefs? Which distribution do individual beliefs about bank stability follow? Does the social planner have all the information to maximise the relevant measure of social welfare? In the absence of a welfare criterion that is widely accepted, we consider different criteria under different cases. In particular, our welfare analysis: (i) considers the entire range of possible values for the actual probability of a bank run and for individual beliefs about such probability; (ii) allows for different distributions of individual beliefs; (iii) differentiates between the case in which individual welfare depends on the probability of a bank run and that in which it depends on individual beliefs about such probability; and (iv) distinguishes between the case in which the social planner has all relevant information and knows the relevant measure of social welfare and that in which she has to estimate it.

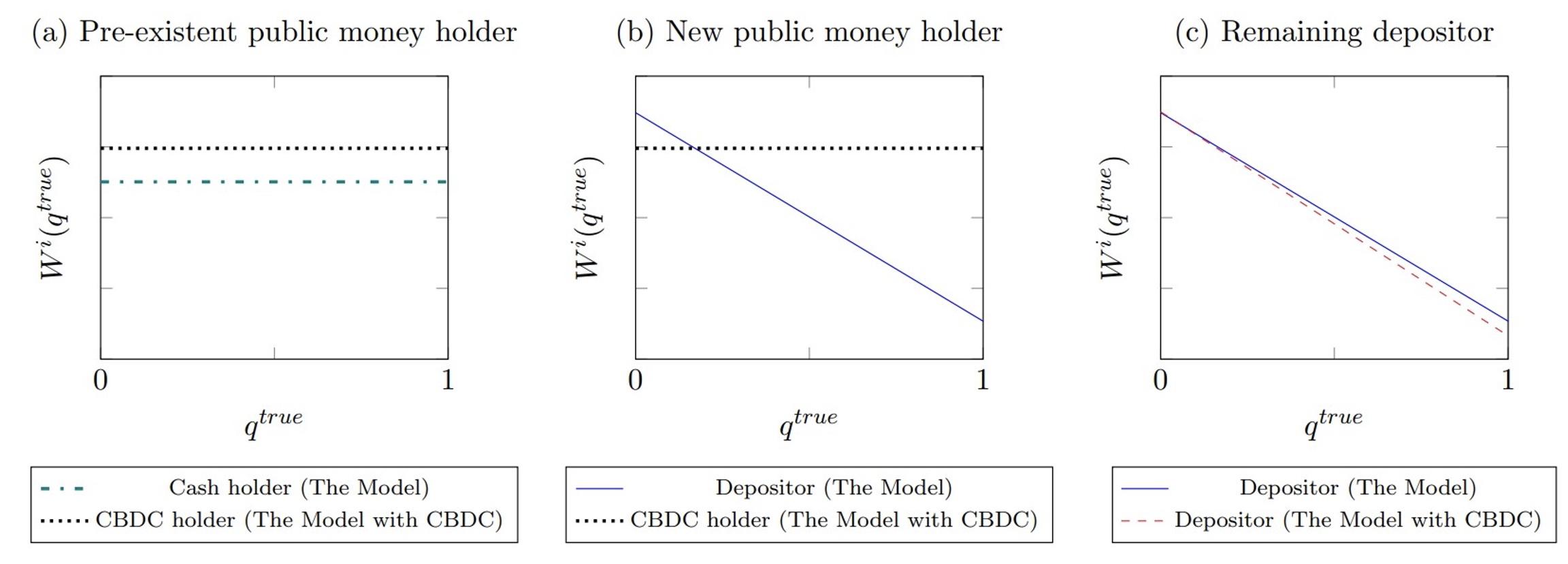

Figure 4 displays simulated individual welfare effects of CBDC by the three consumer types (classified according to their individual beliefs) for the benchmark Case one, in which individual welfare depends on the probability of the bank run (rather than on individual beliefs) and the social planner knows such probability. The figure shows that, even in the simplest case, the adoption of CBDC has heterogeneous welfare consequences across the population, with such consequences depending on actual bank stability.

Figure 4 Simulated individual welfare by consumer type in Case one

Source: Muñoz and Soons (2023).

Notes: The figure displays simulated individual welfare under Case 1 in The Model with and without CBDC for each type of consumer and the entire range of values for the objective probability of a bank run.

We summarise the main findings of our welfare analysis as follows. First, cash holders always benefit by fully switching to CBDC. Second, those consumers who switch from deposits to CBDC based on their beliefs also benefit unless individual welfare depends on the true probability of a bank run and such probability is sufficiently low. Third, in general, depositors are worse off with the introduction of CBDC as a store of value, although the most optimistic ones may benefit if individual welfare depends on their own beliefs rather than on actual bank stability. After aggregating these heterogeneous welfare effects and considering various welfare criteria, we conclude that the introduction of an unremunerated CBDC as a store of value improves social welfare unless the majority of the population relies on bank deposits as a store of value and individual welfare depends on the actual probability of a bank run, with such probability being sufficiently low.

Concluding remarks

The introduction of a CBDC as a store of value in The Model induces a certain degree of bank disintermediation as some of the pre-existent depositors opt for switching to CBDC on the basis of their individual beliefs about bank stability and the fact that holding CBDC is less costly than storing cash. Our analysis presents two interesting corollaries to this result. First, due to the optimal rebalancing response by banks, lending falls less than one-for-one with deposits and relative maturity transformation increases. Second, despite this bank disintermediation effect, the introduction of CBDC as a store of value increases social welfare in a wide range of relevant cases due to the powerful benefit of increasing the efficiency of storing public money in an environment characterised by heterogeneous beliefs and disagreement about bank stability.

References

Adalid, R, R Adalid, Á Álvarez-Blázquez, K Assenmacher, L Burlon, M Dimou, C López-Quiles, N M Fuentes, B Meller, M Muñoz, P Radulova and C R d’Acri (2022), “Central bank digital currency and bank intermediation: Exploring different approaches for assessing the effects of a digital euro on euro area banks”, ECB Occasional Paper, No. 293.

Ashworth, J and C Goodhart (2020), “Coronavirus panic fuels a surge in cash demand”, VoxEU.org, 17 July.

Auer, R, G Cornelli and J Frost (2020b): “Covid-19, cash, and the future of payments,” Bank for International Settlements.

Baubeau, P, E Monnet, A Riva and S Ungaro (2018), “Flight-to-safety and the credit crunch: a new history of the banking crises in France during the Great Depression”, VoxEU.org, 29 November.

Bindseil, U, and F Panetta (2020), “Central bank digital currency remuneration in a world with low or negative nominal interest rates”, VoxEU.org, 5 October.

Brunnermeier, M K, A Simsek and W Xiong (2014), “A welfare criterion for models with distorted beliefs,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129: 1753–1797.

Burlon, L, C Montes-Galdon, M Muñoz, and F Smets (2022), “The optimal amount of central bank digital currency in circulation”, VoxEU.org, 16 August.

Cooper, R and T W Ross (1998), “Bank runs: Liquidity costs and investment distortions”, Journal of Monetary Economics 41: 27–38.

Davila, E and A Schaab (2022), “Welfare Assessments with Heterogeneous Individuals”, NBER Working Paper 30571.

Diamond, D W and P H Dybvig (1983), “Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity”, Journal of Political Economy 91: 401–419.

ECB (2020), Report on a digital euro, Eurosystem.

ECB (2022), Study on the Payment Attitudes of Consumers in the Euro Area (SPACE).

Ennis, H M and T Keister (2003), “Economic growth, liquidity, and bank runs”, Journal of Economic Theory 109: 220–245.

Fernandez-Villaverde, J, D Sanches, L Schilling and H Uhlig (2020), “Central bank digital currency: central banking for all”, VoxEU.org, 25 April.

Jamet, J, A Mehl, C M Neumann and F Panetta (2022), “Monetary policy and financial stability implications of central bank digital currencies”, VoxEU.org, 13 April.

Jobst, C and H Stix (2017), “The cash comeback: Evidence and posible explanations,” VoxEU.org, 29 November.

Muñoz M and O Soons (2023), “Public money as a store of value, heterogeneous beliefs, and banks: Implications of CBDC”, ECB Working Paper Series No. 2801.

Rosl, G and F Seitz (2021), “Cash and Crises: No surprises by the virus”, IMFS Working Paper Series.

Zamora-Perez, A (2021), “The paradox of banknotes: Understanding the demand for cash beyond transactional use,” ECB Economic Bulletin 2.26.