The return to skill in the labour market is at historically high levels, as the US industrial base continues to shift away from manufacturing and towards services. Even middle-class jobs require some postsecondary education, and substantial postsecondary education is almost necessary to access most high-paying professions.

Consequently, the proportion of students enrolling in college has increased dramatically over the past half-century: in 1970, 51.7% of recent high school graduates attended college; the figure rose to 66.2% by 2019. Total autumn enrolment in US postsecondary institutions increased from 8.6 million to 19.6 million over this same period. This pattern is seen throughout the world. The share of the population with tertiary education has grown between generations in nearly every country (OECD 2022).

This rise in postsecondary enrolment and completion has been driven, in part, by the high average return to collegiate training. However, the average return masks important heterogeneity across a number of dimensions (Lovenheim and Smith, forthcoming). One of the most important is college major or course of study. What type of education and training to invest in is a key decision for individuals, with important implications for higher education policy.

As the return to specific types of skill rises in the labour market (Autor 2014, Deming 2017), a more complete understanding of how major choice affects labour market outcomes is needed to guide both students and policymakers. For students, the rising costs of attending college and associated student debt highlight the value of knowing the labour-market consequences of choosing specific majors. Information that can help students make better postsecondary investment decisions can increase the return they experience and reduce the likelihood they will default on their loans. Students are responsive to such information when making major choices (Wiswall and Zafar 2015a,b, 2021), underscoring the importance of providing them with accurate information.

Understanding the returns to a college major is also relevant for policymakers and higher education administrators making resource allocation decisions. Providing more resources to higher-return majors and programmes can increase the aggregate return to college. Thus, a better understanding of these returns can facilitate more efficient resource allocation within and across postsecondary institutions.

A growing body of research points to the importance of college major choice in determining labour-market outcomes. Mean differences in earnings across majors are at least as large as the earnings gap between high school and college graduates (Altonji et al. 2012). Strong evidence from several countries shows that major choice has a substantial impact on mean earnings – in Chile (Hastings et al. 2013), Italy (Anelli 2018), Norway (Kirkeboen et al. 2016), the UK (Walker and Zhu 2011), and the US (e.g. Bleemer and Mehta 2022, Andrews et al. 2017, Hershbein and Kearney 2014, Hammermesh and Donald 2008). Recent evidence also finds large differences in returns across graduate degrees in the US (Altonji et al. 2022a,b).

Most of the prior research on the return to college majors focuses exclusively on mean effects at specific ages. In new research, we highlight four aspects of the labour-market returns to the choice in major that have hitherto received little attention:

- earnings growth with experience

- cross-sectional differences among workers

- within-worker variance in earnings, and

- different impacts across finer distinctions of course of study and institutions.

Our study (Andrews et al. 2022) estimates the return to college major using administrative data linking all Texas public K-12 students to higher education records, among those attending a public Texas postsecondary institution, along with quarterly earnings records for employees in Texas who work for employers covered by unemployment insurance. Together, these data provide a large sample size, a wealth of pre-collegiate information, and within-year earnings variation that are not available in any other US-based datasets. We use rich pre-collegiate and collegiate data to estimate the return to each major relative to liberal arts (the excluded category).

We account for pre-collegiate test scores, student demographics, and high-school-by-cohort and college-by-cohort effects. Hence, we compare observationally similar students who graduated from the same high school in the same year and who attended the same college (from the same high school cohort) but who differed in terms of their major. While this approach makes the strong assumption that these characteristics are sufficient to account for all differences across students in potential labour-market outcomes, our estimates rely on weaker assumptions than many prior analyses of the returns to college major.

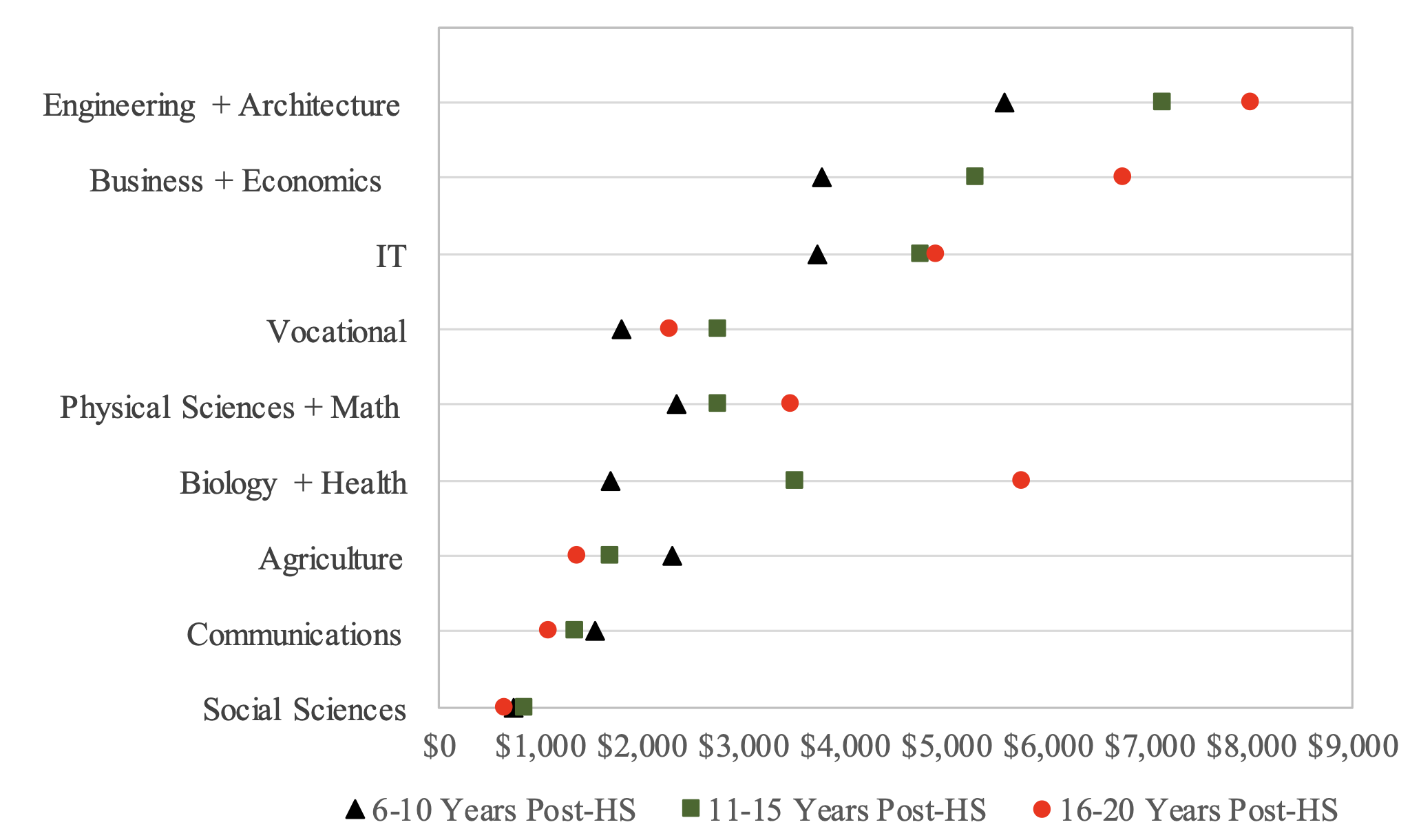

We have four broad findings. First, the returns to college major vary across majors. For example, the relative (to liberal arts) return to a four-year biology/health or economics/business degree doubles or triples after two decades, while relative returns to agriculture, communications, and social sciences (excluding economics) decline substantially with experience. Quarterly premia over liberal arts vary from $664 in social sciences to $8,016 in engineering and architecture, 16–20 years after high school.

Figure 1 Returns to college major by potential experience for BA/BS degree

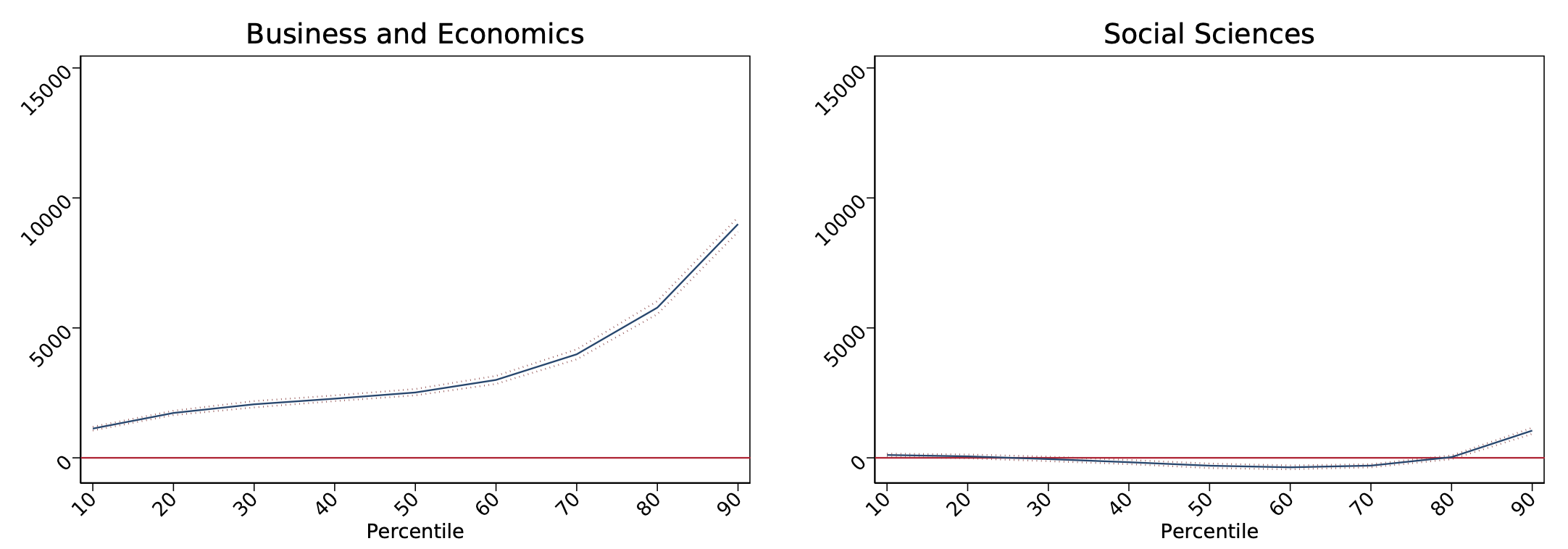

The results further point to important differences in the variance of returns both across and within workers. Quantile treatment effect estimates (DiNardo et al. 1996, Firpo 2007), which compare earnings at each percentile in a given field relative to earnings adjusted for observed characteristics at the same percentile of the liberal arts distribution, indicate much variation across majors in how they influence the distribution of earnings across workers. Some majors shift the earnings distribution relatively uniformly and others generate much larger effects at the top of the distribution. This suggests that the mean effects embed substantial (and differential) ex-ante risk for students. For instance, the small earnings benefit for social sciences reflects no effect for most students and positive effects for those at the top, while business and economics returns are positive and sizeable throughout the distribution, and especially large for those at the top.

Figure 2 Returns relative to same percentile of liberal-arts distribution

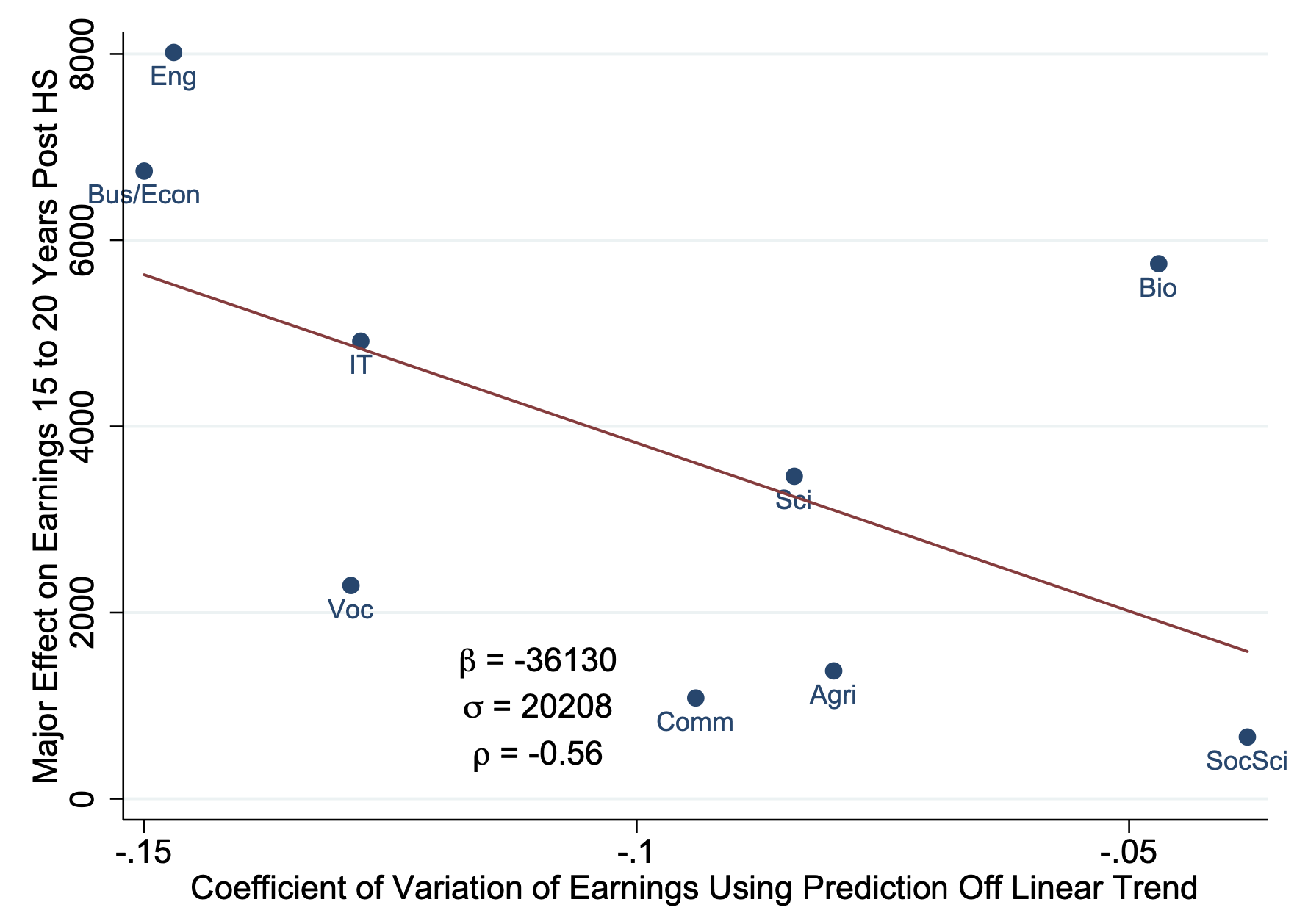

We also show that college majors have a modest, but significant, effect on the within-worker variance in earnings, measured by the coefficient of variation relative to predicted earnings for each worker. Substantial variation in earnings across quarters can reduce worker welfare if workers face credit constraints that preclude them from borrowing to smooth consumption over time and/or exhibit risk aversion.

Most majors have lower earnings variability than liberal arts; however, the magnitude of the gap varies across majors. Overall, mean earning effects are negatively correlated with the coefficient of variation: high-returns majors also have lower earnings variability, making them even more desirable to risk-averse students.

Figure 3 Relationship between mean returns and variability in earnings by major

Most research on college majors uses aggregate major groups, often employing only a small number of highly-aggregated majors. We provide new evidence on the extent of variation in returns across more-narrowly-defined majors within broader major groups, as well as how average major effects vary across postsecondary institutions.

First, we show that there is substantial heterogeneity in returns across the Classification of Instructional Programs four-digit (CIP-4) categories (Figure 4).

There is even more variation in the return to aggregate major categories across institutions, which is suggestive of large programme-specific effects.

Figure 4 Variation in mean earnings effects within major groupings (4-digit CIP codes)

Future research should more carefully consider aggregation decisions across majors and institutions. Differences in findings between previous studies could be due to different aggregation procedures and differences in the set of institutions in the analysis sample.

Our study contributes to the growing literature on the returns to college major by moving beyond an analysis of mean effects at specific ages. We show new evidence on how majors contribute to post-collegiate earnings growth, shift the cross-sectional distribution of earnings, and influence the within-worker variance in earnings. We also explore the role of aggregation. Using rich administrative data allows us to control extensively for selection into different majors.

Taken together, we highlight the importance of understanding the various dimensions of the returns to college major. It can both help students make more informed decisions about their majors and enable policymakers and higher-education administrators to make better resource allocation decisions.

References

Andrews, R J, S A Imberman, M F Lovenheim and K M Stange (2022), “The returns to college major choice: Average and distributional effects, career trajectories, and earnings variability”, NBER Working Paper w30331.

Andrews, R J, S A Imberman and M F Lovenheim (2017), “Risky business? The effect of majoring in business on earnings and educational attainment”, NBER Working Paper w23575.

Altonji, J G, E Blom and C Meghir (2012), “Heterogeneity in human capital investments: High school curriculum, college major, and careers”, Annual Review of Economics 4(1): 185–223.

Altonji, J G, J E Humphries and L Zhong (2022a), “The effects of advanced degrees on the wage rates, hours, earnings and job satisfaction of women and men”, NBER Working Paper w30105.

Altonji, J G, J E Humphries and L Zhong (2022b), “The value of graduate school depends on your gender and choice of degree”, VoxEU.org, 14 September.

Anelli, M (2018), “The labor market determinants of the payoffs to university field of study”, unpublished working paper, 15 February.

Autor, D H (2014), “Skills, education, and the rise of earnings inequality among the ‘other 99 percent’”, Science 344(6186): 843–51.

Bleemer, Z, and A Mehta (2022), “Will studying economics make you rich? A regression discontinuity analysis of the returns to college major”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 14(2): 1–22.

Deming, D J (2017), “The growing importance of social skills in the labor market”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(4): 1593–640.

DiNardo, J, N M Fortin and T Lemieux (1996), “Labor market institutions and the distribution of wages, 1973–1992: A semiparametric approach”, Econometrica 64(5): 1001–44.

Firpo, S (2007), “Efficient semiparametric estimation of quantile treatment effects”, Econometrica 75(1): 259–76.

Hamermesh, D S, and S G Donald (2008), “The effect of college curriculum on earnings: An affinity identifier for non-ignorable non-response bias”, Journal of Econometrics 144(2): 479–91.

Hastings, J S, C A Neilson and S D Zimmerman (2013), “Are some degrees worth more than others? Evidence from college admission cutoffs in Chile”, NBER Working Paper w19241.

Hershbein, B, and M Kearney (2014), “Major decisions: What graduates earn over their lifetimes”, Washington, DC: Hamilton Project.

Kirkeboen, L J, E Leuven and M Mogstad (2016), “Field of study, earnings, and self-selection”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(3): 1057–111.

Lovenheim, M and J Smith (forthcoming), “Returns to Different Postsecondary Investments: Institution Type, Academic Programs, and Credentials”, Working Paper.

OECD (2022), “Population with tertiary education”, Education at a glance: Educational attainment and labour-force status database.

Walker, I, and Y Zhu (2011), “Differences by degree: Evidence of the net financial rates of return to undergraduate study for England and Wales”, Economics of Education Review 30(6): 1177–86.

Wiswall, M, and Zafar, B (2015a), “Determinants of college major choice: Identification using an information experiment”, Review of Economic Studies 82(2): 791–824.

Wiswall, M, and Zafar, B (2015b), “How do college students respond to public information about earnings?”, Journal of Human Capital 9(2): 117–69.

Wiswall, M, and Zafar, B (2021), “Human capital investments and expectations about career and family”, Journal of Political Economy 129(5): 1361–424.