In many countries, students specialise at secondary school, choosing fields of study to prepare for college or obtain vocational training (OECD 2019). Do these early field choices made as a teenager have long-run consequences for future earnings? This is an important question for education policy when considering how to allocate schooling resources and slots across fields. From the perspective of students, information on field-specific earnings premiums could help them plan better for their future.

Despite the importance of the issue, there is little evidence on the returns to different academic fields of study in secondary school. Altonji et al. (2012) develop a dynamic model that highlights the roles of preferences, ability, and future wages in field choice, and emphasise the difficulty of estimating causal effects. The fact that individuals do not randomly sort into fields of study, but rather may choose fields they are better at, makes solving the issues they identify formidable. In recent years, some progress has been made in estimating causal returns to different university majors (Hastings et al. 2013, Kirkeboen et al. 2016, Andrews et al. 2017), but similar analyses do not exist for fields of study in secondary school. The secondary school margin is distinct and important in its own right, as field decisions are made at the end of ninth grade (UK Year 10), when students are only 16 years old. These youth likely have limited information on their tastes and talents for different fields, as well as limited information on how these choices will affect their future careers. Whether secondary school fields have lasting ‘lock-in’ effects on earnings is an important policy question.

Admission to fields of study in Sweden

In recent work (Dahl et al. 2020), we take advantage of the admissions system in Sweden’s secondary schools to estimate field-specific returns. In Sweden, students choose between five different academic fields: engineering, natural science, business, social science, and humanities. They also have the choice of several non-academic programmes. At the end of ninth grade, students rank their preferred fields, and if a field is oversubscribed, admission is determined by the student’s cumulative grade point average (GPA). This allows us to compare future wages for individuals just above versus just below the GPA admission cut-offs for different fields of study. These individuals should be virtually identical on all observable and unobservable margins at the time of admission, except for the fact that those just above the cut-off get into a different field of study. These comparisons are for students on the margin of admission, rather than the general population. Fortunately, this is a relevant group from a policy perspective, as reforms which expand or contract different fields target exactly these individuals. We focus on individuals with an academic preferred choice, as the non-academic fields are rarely oversubscribed.

Our setting also allows us to account for an individual’s next-best alternative field of study. For example, we can estimate the return to engineering separately for students who otherwise would have got into natural science versus business. This is important both because the relevant counterfactual field changes and because aptitude for engineering could be quite different for the two types of students. As Kirkeboen et al. (2016) explain, accounting for these second-best choices is critical for identifying interpretable estimates.

Returns to different fields

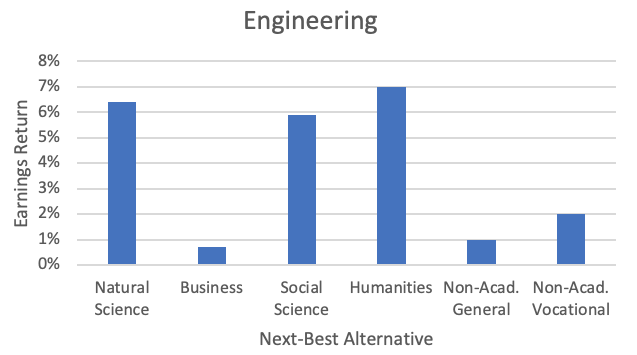

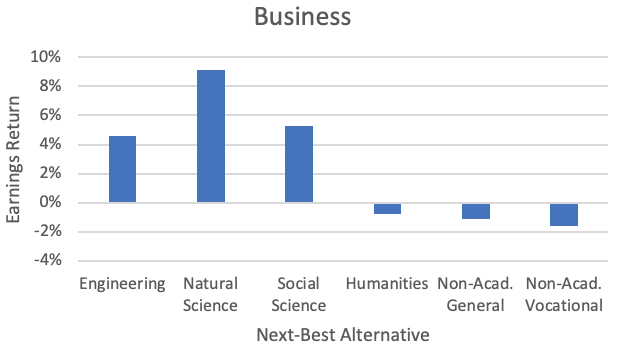

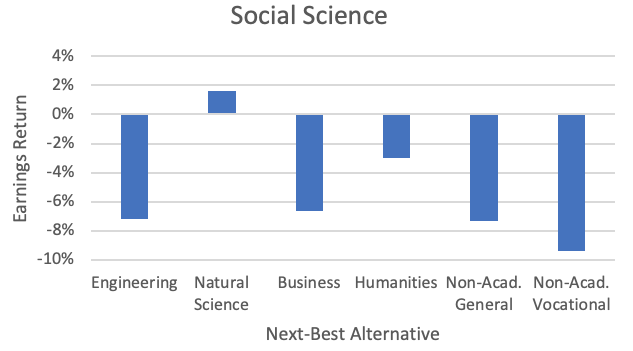

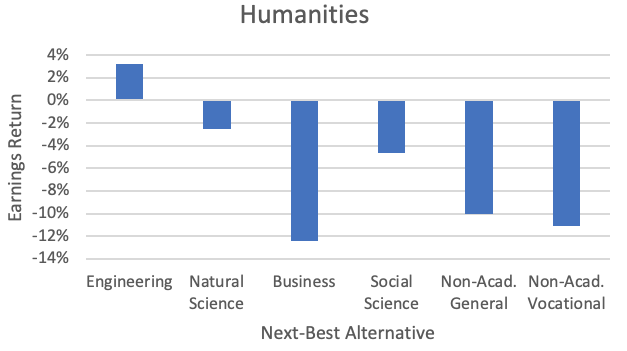

Using Sweden’s high-quality register data, we are able to link fields of study in secondary school to the earnings of these same individuals when they are in the prime of their working careers. Figure 1 displays the estimated earnings return to completing one’s first-best field choice compared to the next-best choice. These estimates scale the earnings effect of getting into a program by the increased probability of completing a programme (since some individuals switch fields before the start of the school year or soon thereafter).

The graphs document two key patterns. First, the earnings payoffs to different fields of study varies, and can be either positive or negative. For example, the returns to engineering are always positive, ranging from 0.7% to 7.0% depending on an individual's next-best alternative field of study. In contrast, the returns to social science range from -9.4% to 1.6%. Summarising the five panels in the figure, earnings payoffs are generally positive or close to zero for engineering, natural science, and business. In contrast, the returns to social science and humanities are mostly negative, even when compared to next-best non-academic programs.

The second pattern seen in Figure 1 is that returns depend on next-best alternatives. For example, there is a 9.1% return to completing Business relative to a second-best choice of natural science, but essentially no return to completing business (-0.8%) for those who have humanities as their next-best alternative. This contrast makes clear than those who chose natural science as their second-best choice are not directly comparable to those with humanities as their next-best choice. While not shown here, formal tests reject the hypothesis that second-best choices do not matter for each of the field-specific returns.

Figure 1 Returns to completed field of study relative to the next-best alternative

Comparative advantage and other mechanisms

The pattern of returns in Figure 1 is consistent with the pursuit of comparative advantage in expected earnings for many field choice combinations, but not all. For example, individuals who complete natural science with a second-best choice of business earn a 5.6% premium, while those who complete business with a second-best choice of natural science earn a 9.1% premium. Random sorting would have predicted the two estimates were equal in magnitude, but opposite in sign. In other words, this is evidence of individuals with a comparative advantage in business choosing it over natural science, and vice versa. Five field combinations show evidence for comparative advantage, two for comparative disadvantage, and three for random sorting. Summarising the patterns, comparative advantage occurs most often when first- and second-best choices include engineering, business, or natural science. Comparative disadvantage, which happens when individuals choose fields they earn less in, is linked to humanities. Comparative disadvantage could imply either than individuals are not aware of their earnings differences across fields or that they value non-pecuniary aspects of a field.

In additional analyses, we find that most of the differences in adult earnings across fields of study can be explained by differences in occupation, and to a lesser extent, college major. For example, individuals who complete business instead of social studies earn more as adults in part because they pursue higher-paying college majors (e.g. an accounting major versus a psychology major) but to an even greater extent because they end up in higher paying occupations (e.g. a sales manager versus a social worker), even after accounting for their college major. In contrast, once these other two mechanisms are accounted for, years of schooling is not an important factor.

Concluding remarks

The magnitude and variability of the field-specific earnings returns we document are large, with the absolute value of many of the estimates exceeding the return to an additional two years of education in Sweden (Meghir and Palme 2005, Black et al. 2018). This information is relevant for students, parents, and school counsellors, especially since preferences and skills are still in flux at such a young age. The findings are also valuable for policymakers deciding how to best structure and reshape secondary education, including whether to relax enrolment limits or provide incentives to study one field over another.

Authors’ note: This column is based on research by the authors (Dahl et al. 2020), which received generous financial support from The Swedish Research Council.

References

Altonji, J, E Blom and C Meghir (2012), “Heterogeneity in human capital investments: High school curriculum, college major, and careers”, Annual Review of Economics 4: 185–223.

Andrews, R, S Imberman and M Lovenheim (2017), “Risky business? The effect of majoring in business on earnings and educational attainment”, NBER Working Paper No. 23575.

Black, S, P Devereux, P Lundborg and K Majlesi (2018), “Learning to take risks? The effect of education on risk-taking in financial markets”, Review of Finance 22: 951–975.

Dahl, G, D Rooth and A Stenberg (2020), “Long-run returns to field of study in secondary school”, NBER Working Paper No. 27524.

Hastings, J, C Neilson and S Zimmerman (2013), “Are some degrees worth more than others? Evidence from college admission cutoffs in Chile”, NBER Working Paper No. 19241.

Kirkeboen, L, E Leuven and M Mogstad (2016), “Field of study, earnings, and self-selection”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 1057–1111.

Meghir, C and M Palme (2005), “Educational reform, ability, and family background”, American Economic Review 95: 414–424.

OECD (2019), Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing.