Communication is now a critical aspect of monetary policy design. Central banks routinely announce inflation targets and their plans for achieving them in the form of ‘forward guidance’. Household and firm surveys of inflation expectations are conducted to identify the extent to which these announcements achieve their goal of being credible and comprehensible.

In contrast, policy communication is not a focus of social security reform. This is despite the fact that reforms in social security eligibility are being implemented around the world to make people work longer and reduce public expenditures that are growing as a result of the increase in life expectancy (Börsch-Supan and Coile 2018). They are typically announced years in advance to give people time to prepare for the future. For this to work, it is important that people are well-informed about eligibility rules. It is normally taken for granted that people know the rules, but we know almost nothing in practice about whether people are informed or not.

Denmark is a particularly striking case in point: it put in place plans for major changes in eligibility age back in 2006, far earlier than other countries and more ambitious in scope. This reform replaced a long-standing policy of universal social security eligibility at age 65 with longevity-based eligibility, and that information was made public. The reform changed only the eligibility age without changing other features of the social security benefits system. Given this one-dimensional nature, the salience of the eligibility age, and the online availability of policy plans, one might expect the public to be aware of planned increases in the eligibility age.

It is an open question whether there is a gap between actual policy and public perception, and also what the role of information and uncertainty about policy plans related to the distant future is (Kosar and O’Dea 2021, Ciani et al. 2019). Certainly, in the Danish case, the eligibility age is a moving target. It was announced in 2006 that the transition would start in 2024, but in 2011 the parliament decided to start in 2019 instead. Moreover, the policy is explicitly based on demography: every five years, the age thresholds will be updated based on the development of life expectancy, with the decision to take effect 15 years later.

To study awareness of the reform, we invited a representative sample of more than 10,000 people to participate in a customised survey (Caplan et al. 2022). The survey elicited the entire subjective distribution concerning retirement eligibility age beliefs using the ‘balls-in-bins’ method proposed by Delavande and Rohwedder (2008), where the respondent is asked to allocate 20 balls into bins covering the possible social security eligibility ages within the age span of 63 to 74. This method uncovers the subjective probability distribution over the respondent’s own eligibility age and makes it possible to measure individual mean beliefs and individual uncertainty.

As a part of the survey, we implemented a simple information treatment experiment where we randomly selected half of the sample and showed them a table with the eligibility ages that are publicised on the home page of the Ministry of Employment before they answered the question about beliefs about their social security eligibility age.

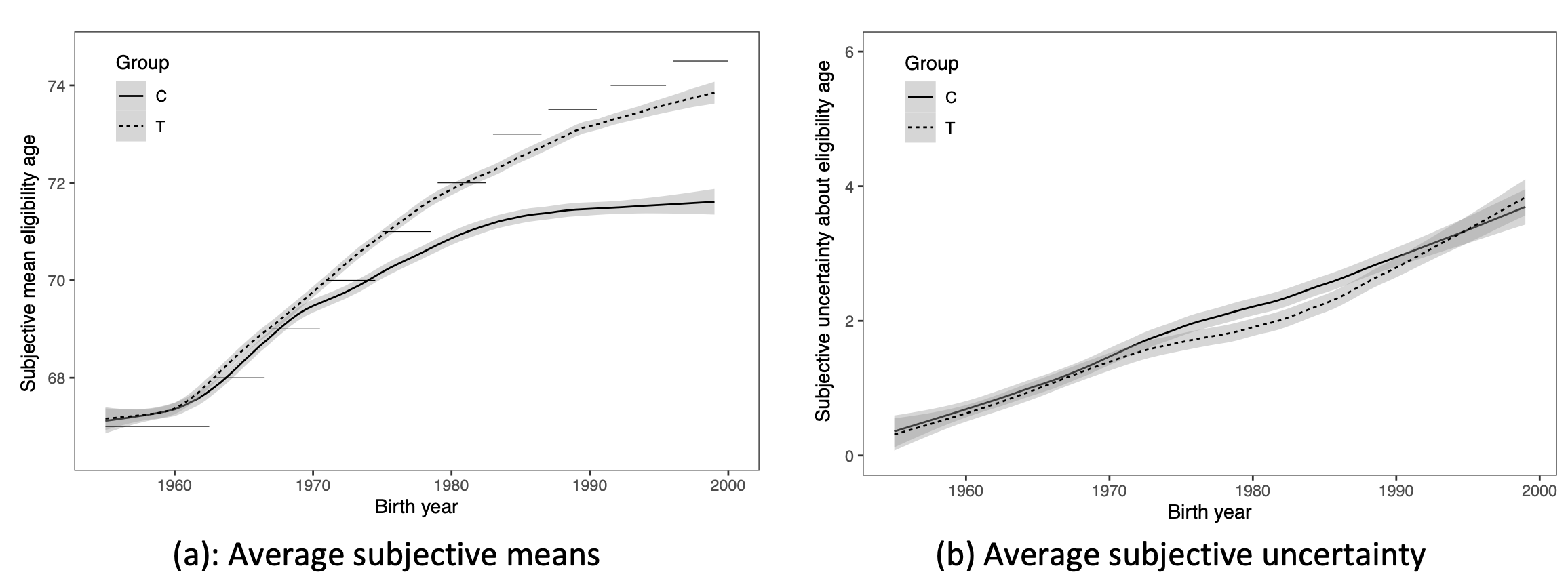

The main result is presented in Panel (a) of Figure 1. The horizontal lines show the actual eligibility age of the different birth cohorts. The solid line shows the average eligibility age beliefs for the control group, i.e. people who are not shown in the table with statutory eligibility ages. People born before 1970 are well-informed about their eligibility age, but people born after 1970 systematically underestimate the age at which they become eligible. This latter group, on average, expects to become eligible up to one year earlier than their statutory eligibility age. The dashed line shows the average beliefs in the treatment group, i.e. the group of people who were shown in the table with statutory eligibility ages. A comparison of the two groups in the figure shows that the information treatment reduced the gap between expected and statutory eligibility ages by 80%. In other words, the very simple information treatment is successful in updating people’s beliefs to be closely aligned with the rules.

Panel (b) shows the average subjective uncertainty for treatment and the control group. Uncertainty is increasing in the number of years to eligibility, but remarkably, the information treatment has no effect on perceived uncertainty. This might reflect that social security eligibility is inherently associated with policy uncertainty that cannot be removed.

Figure 1 Social security eligibility beliefs

Notes: Lines show locally weighted linear regressions for control (solid) and treatment (dotted) groups for subjective mean eligibility ages, Panel (a), and subjective uncertainty measured as the subjective variance of eligibility ages, Panel (b). In Panel (a), horizontal lines show official eligibility ages. ‘T’ indicates the group that is information-treated, and ‘C’ indicates the group that is not information-treated. The shaded areas indicate 95% point-wise confidence intervals.

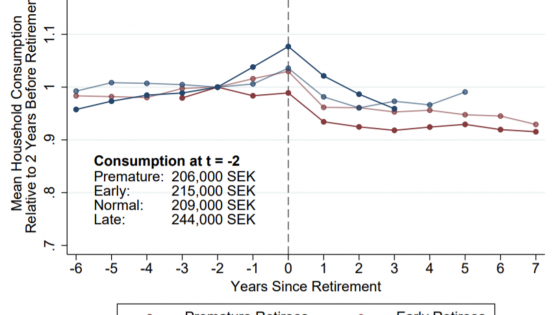

Social security eligibility is a circumstance and not a choice, but retirement is a choice, and previous studies have shown that retirement is sensitive to social security eligibility (e.g. Magesan et al. 2021, Kanninen et al. 2020). We also consider how the information treatment affects people’s retirement plans, and we find that the information treatment affects people’s retirement plans in the same direction as their eligibility beliefs. This suggests that knowledge does matter for people’s retirement planning.

Our study offers a new method to quantify the lack of knowledge about policy rules and the importance of policy uncertainty. The results demonstrate how simple information provision can align the beliefs about policy rules with the actual rules for the vast majority of people. Our results highlight the importance of incorporating communication strategies, including belief measurement and information treatments, into policy design outside the monetary policy arena.

References

Börsch-Supan, A H and C Coile (2018), “Social Security Programs and Retirement around the World: Reforms and Retirement Incentives–Introduction and Summary”, NBER working paper 25280.

Caplin, A, Lee, Leth-Petersen and Sæverud (2022), “Communicating Social Security Reform”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP17687.

Ciani, E, A Delavande, B Etheridge and M Francesconi (2019), “Policy Uncertainty and Information Flows: Evidence from Pension Reform Expectations”, Economic Journal (forthcoming).

Delavande, A and S Rohwedder (2008), “Eliciting Subjective Probabilities in Internet Surveys,” Public Opinion Quarterly 72: 866–891.

Kanninen, O, T Ravaska and J Gruber (2020), “Relabelling, Retirement, and Regret”, VoxEU.org, 22 Nov.

Kosar, G and C O’Dea (2022), “Expectations Data in Structural Microeonomic Models,” chapter 21 in Handbook of Economic Expectations (Editors: Ruediger Bachmann, Giorgio Topa, Wilbert van der Klaauw), Elsevier.

Magesan, A, S Staubli and R Lalive (2021), “The Impact of Social Security on Pension Claiming and Retirement”, VoxEU.org, 12 Jan.