Poland’s central bank cut interest rates in a move that is widely seen as politically motivated. The Bank of Brazil is under pressure to do the same. The Federal Reserve, under the Trump administration, was very publicly under pressure to keep rates down. What happens when a central bank is forced to keep policy rates low?

There are two answers to this question. The widely accepted answer, going back to early days of modern monetary policy analysis, is that inflation will go up and in open economies the currency will depreciate. Strikingly, in a recent Vox column, Masciandaro et al. (2023) argue that monetary expansion led to depreciation even in 17th century Venice. There is also an alternative answer, suggesting that persistently low interest rates will lead to lower inflation and as a result an appreciating currency. This idea, formalised by Uribe (2017, 2022) and Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2022) in a series of papers and labelled ‘neo-Fisherian disinflation’, is a tricky one. Can countries lower inflation and appreciate their currencies by cutting policy rates?

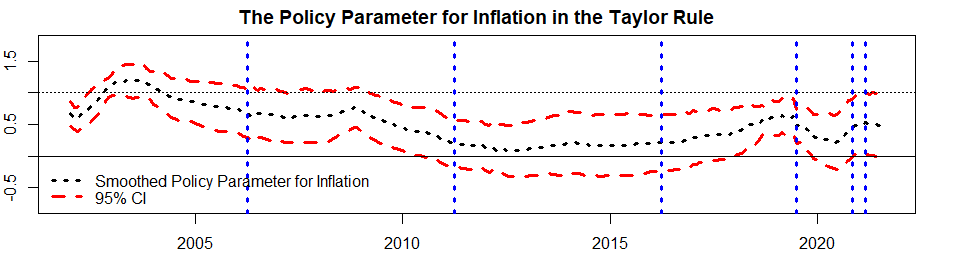

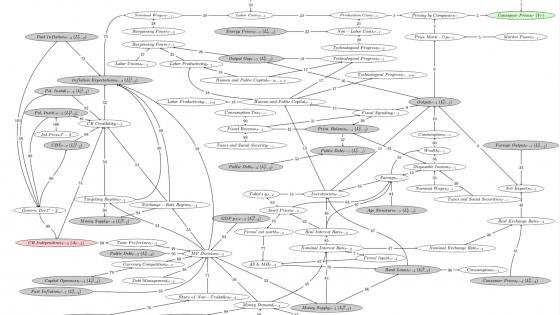

The Turkish experience is instructive in answering the question. In recent work (Gürkaynak et al. 2023), we studied this long-lasting experiment in low interest rates that we dated as going back to 2010. In this period, Turkey kept interest rates lower than any standard monetary policy rule would suggest in the face of rising inflation. Figure 1 shows our estimate of the central bank’s reaction to inflation, with a clear break around 2010, when the estimated parameter first declined below unity and soon after became statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Figure 1 The Taylor rule with time-varying parameters

Notes: Vertical dotted lines denote tenures of the central bank governors.

It is worth noting that in 2010, Turkey had a low debt-to-GDP ratio, historically low credit default swap (CDS) rates, and was moved to investment grade soon after the beginning of the low interest rate experiment, implying that the rates were not kept low due to fiscal considerations. The decline in the central bank’s response to inflation was not because of fiscal necessity but rather due to a change in central bank preferences amid political pressure.

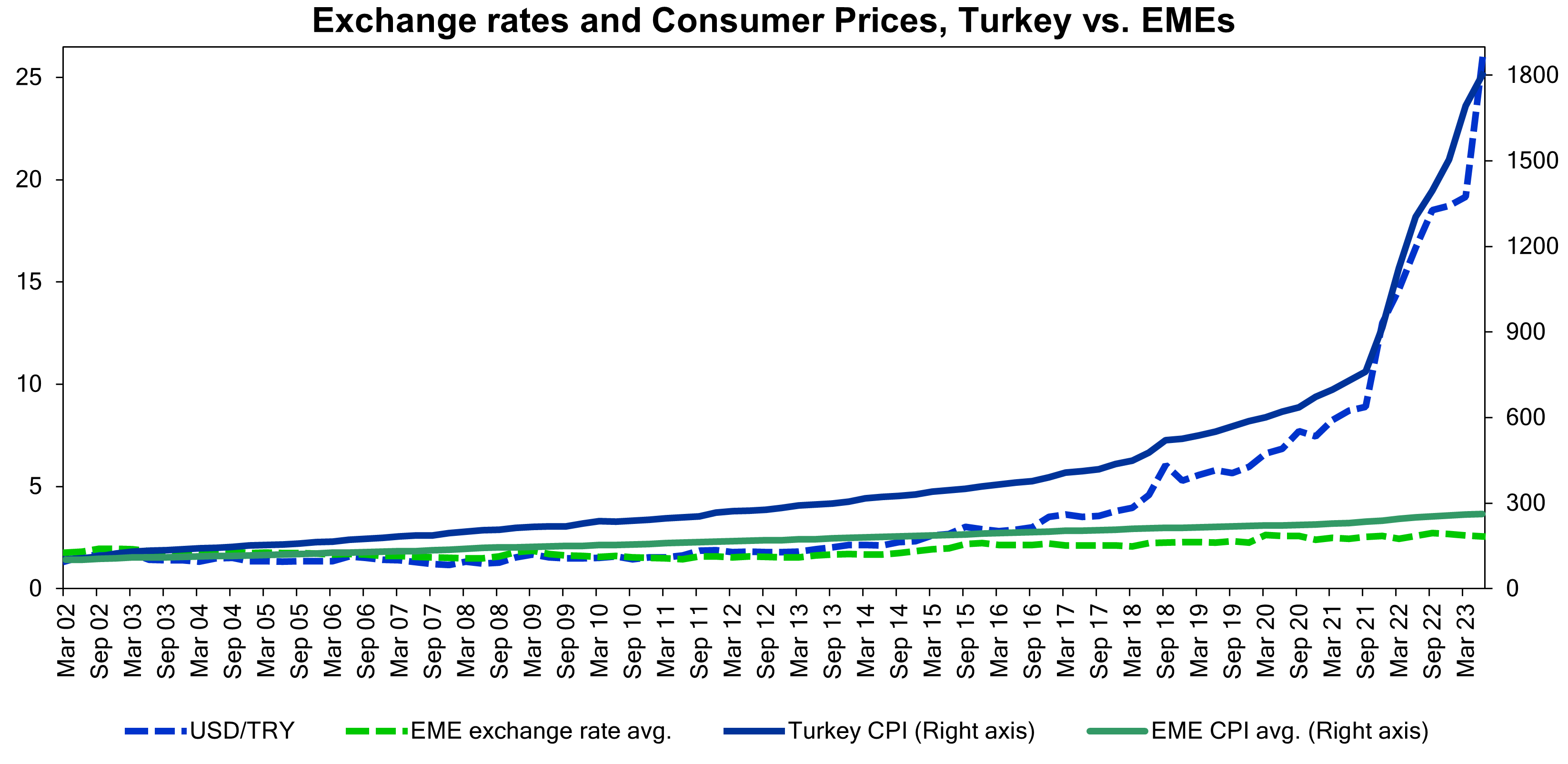

The result was not neo-Fisherian at all. Turkey decoupled from other emerging markets, with the lira strongly depreciating against the dollar and inflation shooting up, as shown in Figure 2. This joint behaviour of inflation and the exchange rate is reminiscent of a purchasing power parity relationship, which we formally test and verify. Although very destructive for its citizens, the Turkish policy framework created a large exogenous change that is useful to test a variety of hypotheses. We focus on monetary policy applications; others will hopefully pick up different aspects.

Figure 2 Exchange rate and price level: Turkey vs. emerging market average

Notes: The emerging market economies (EMEs) are Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia, Korea, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, and Thailand. Indices are normalised to 2002:M1=100.

One natural question is to ask, in an environment of high and volatile inflation, why people were holding the lira at all. There are two answers to this. First is the expectation that sanity would prevail and monetary policy will normalise. This, in essence, is a public belief in regime switching, with a ‘normal’ policy regime where the central bank reacts to inflation strongly waiting to happen in the future. (In the event, there were episodes of such normalisation verifying the expectation and one such policy change is now ongoing.) The second reason is the difficulty of completely abandoning the local currency. Although there was a rapid increase in the dollar denominated deposits, civil servants were still paid in liras and taxes still had to be paid in liras, as well as new legal requirements to force private contracts to be in liras. This is why Benati (2023) shows that there was no Laffer curve in benefits from monetisation even in interwar Germany. Local currency does not die quickly, even in very high inflation environments.

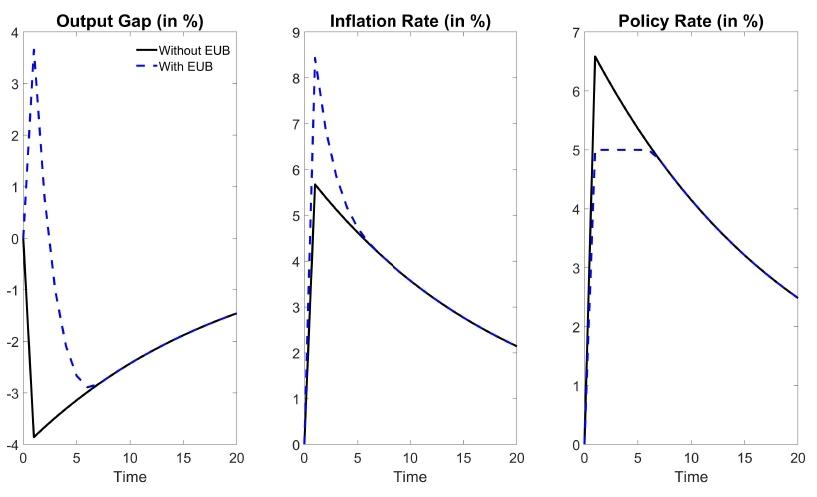

In analyses of time variance in policy rules, regime switching monetary policy is well studied. It allows asking how macroeconomic variables would behave under a weak regime versus a strong one in response to an inflationary shock. As expected, in weak regimes shocks affect inflation more because the central bank does not sufficiently offset them. However, this effect is symmetric. That is, we should expect to see very large downswings in inflation as well as upswings. That, clearly, was not the case in Turkey, or elsewhere with similarly weak policy. Inflation increased arbitrarily but we did not see deflation at all. This observation leads us to argue that, rather than a policy that is unconditionally unresponsive to inflation, an effective upper bound is a better way to think about monetary policy under political pressure. Under an effective upper bound, negative shocks to inflation can be offset by the central bank, but not shocks that push inflation up due to political constraints. Figure 3 illustrates inflation dynamics when there is an exogenous shock to inflation and the upper bound is binding.

Figure 3 Impulse response functions based on a New Keynesian model with the effective upper bound on the policy rate

Notes: The solid line is the reaction without the effective upper bound on the policy rate and the dashed line is the reaction with it, both in response to two standard deviation positive shocks to the output gap and the inflation rate.

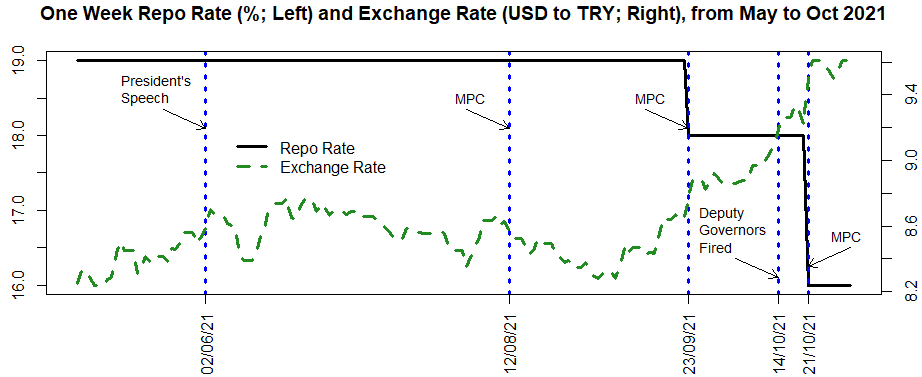

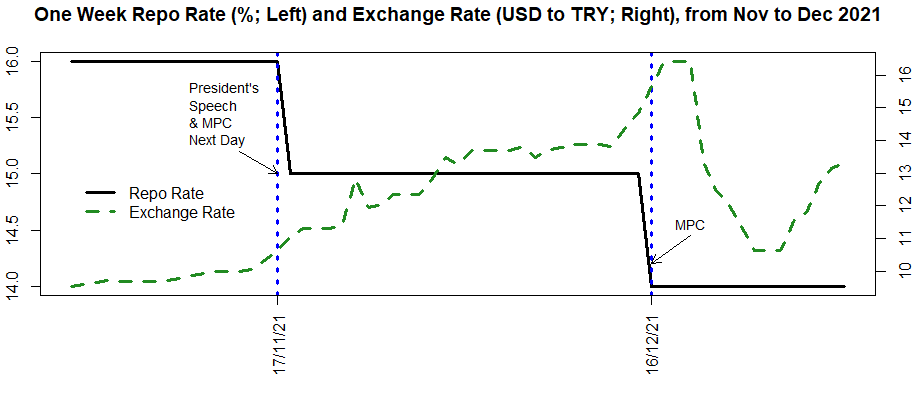

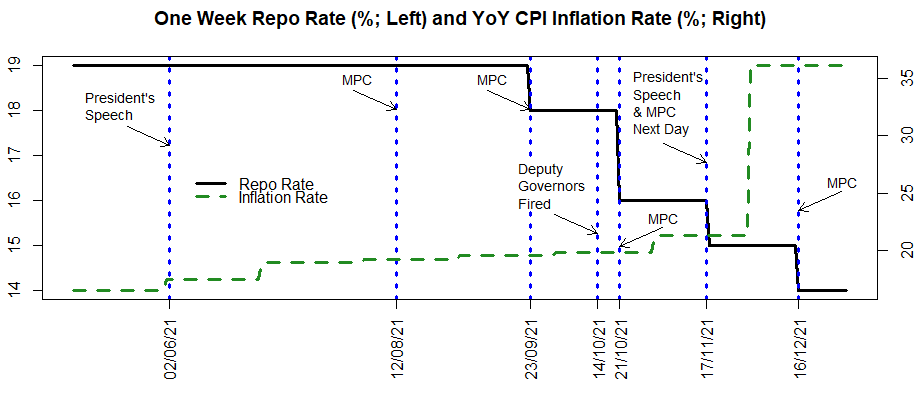

Weak monetary policy, on the whole, is very destructive and that destruction comes in waves. First, the exchange rate jumps. This was immediate in Turkey, when policy became politically hindered in 2010 as was shown in Figure 1, but became even more pronounced when the Central Bank of Turkey (CBRT) began to cut rates in the face of rising inflation in the fall of 2021 (Figure 4). Rising prices followed quickly. Turkey saw inflation going up to 85% in short order. These are all as expected, based on standard theory.

Figure 4 Policy rate, inflation, and exchange rate

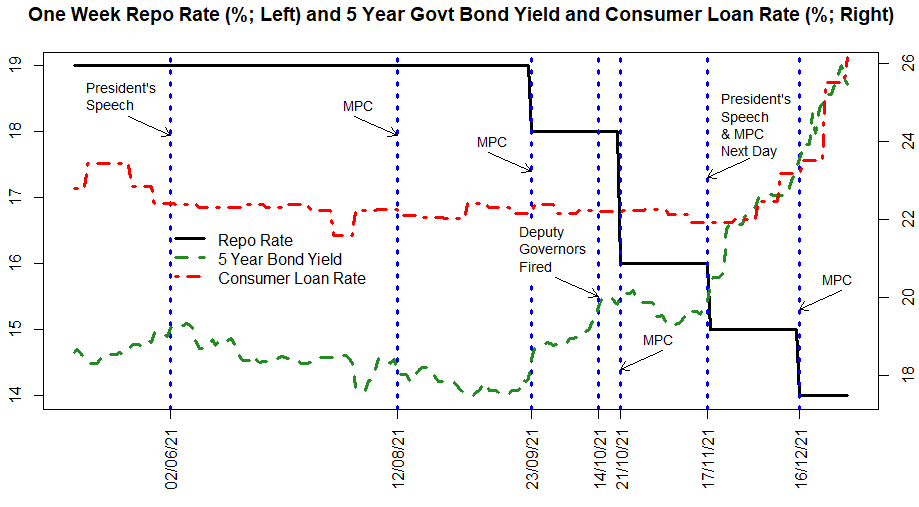

More interesting is the behaviour of market rates and what followed. Figure 5 shows that as the Central Bank of Turkey was cutting its policy rate, longer term loan rates for households, firms, and the government’s borrowing costs were going up. This, too, is expected when the public updates their expectations of long-term inflation based on current developments (Gürkaynak et al. 2005). But cutting policy rates for political reasons and ending up with higher market rates is a particularly sad combination.

Figure 5 Long-term loan rates

Policymakers who pursue such strategies do not take it well when their plans are foiled by predictable market forces. The next step is often financial repression and Turkey was no exception. Through bank regulation that makes banks hold long-term government bonds and strong suasion, long rates were forced lower. There were days when the ten-year lira borrowing rate of the government was below its borrowing costs in dollars, even though inflation in Turkey was an order of magnitude higher than that in the US, and the lira was depreciating rapidly. In this process, more and more interest rates and lending decisions became administrative decisions rather than being market determined.

At the same time, monetary policy communication took a hit as the central bank continued to emphasise its ‘tight monetary policy stance’ while cutting rates to imply a -50% real policy rate and used convoluted mechanisms to try to stem the fallout from this. The central bank of Turkey engineered various ways to influence the relevant market rates without changing the official policy rate, including using the discount rate as a policy tool and offering off-market exchange rates for reserves held in foreign currency. This set of policies became so complicated that the policy stance was about impossible to communicate. Central Bank of Turkey paid dearly for this policy framework in terms of runaway inflation that went above 15 times its target.

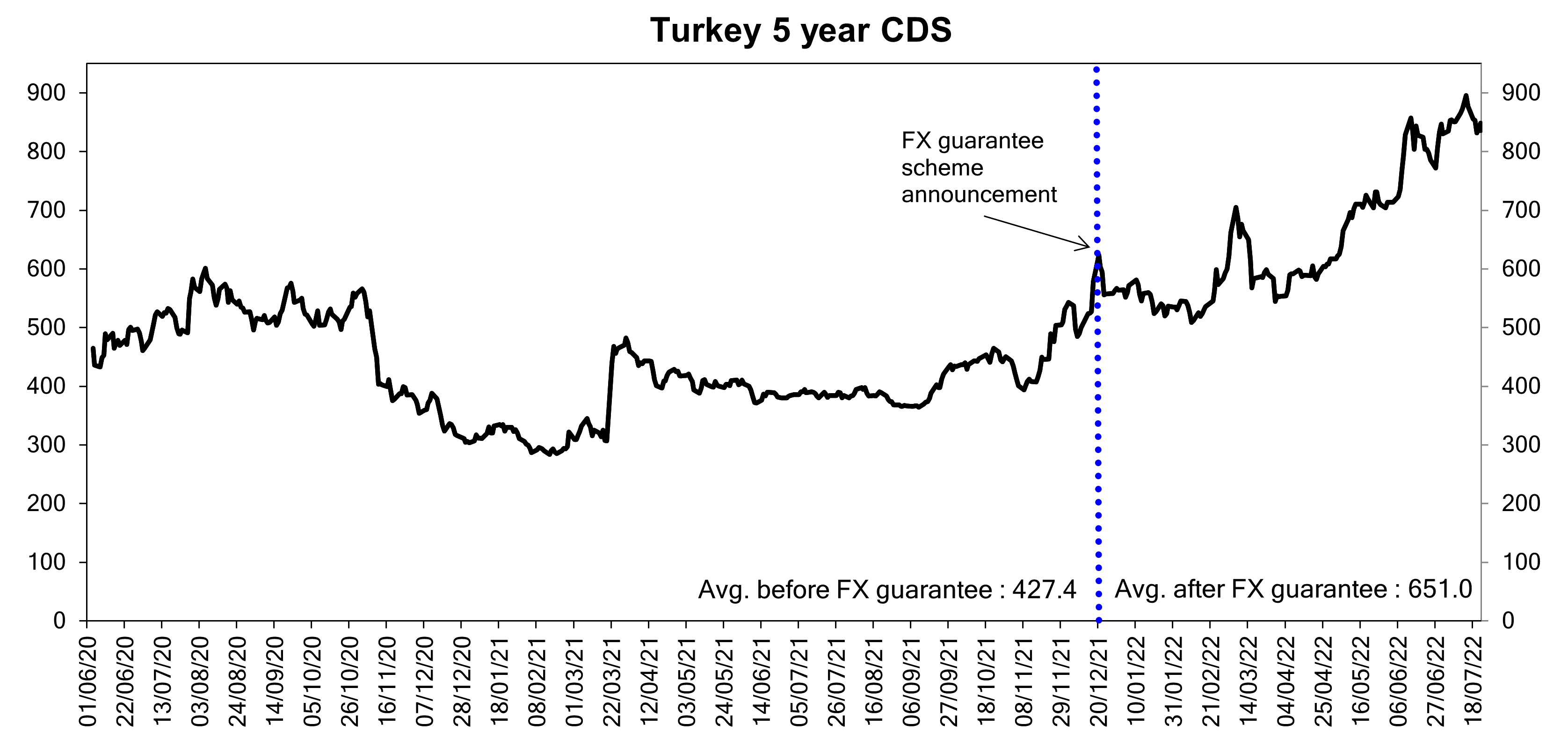

The noteworthy point here is that political pressure for low rates (as in Turkey in 2010 and after) is often the thin edge of the politisation of monetary and financial policy wedge. When market forces get in the way of politically desired outcomes, non-market interventions intensify. In Turkey, these led to a web of regulations that is now very difficult to disentangle. A particularly difficult mechanism to unwind is the exchange-protected lira accounts. The government instituted accounts with a free call option on the dollar-lira exchange rate for the holders of these accounts, to stop a rush to dollars. The premise was to make holders of these accounts whole if, at maturity, the interest earned in liras was below what one would have made had they held dollars for the duration. This was announced on a midnight and while most people were trying to understand what the mechanism is, financial markets had priced in the fact that Turkey had converted exchange rate risk to government budget risk (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Credit default swap event study

After the May 2023 elections, the government changed the leadership of the Central Bank of Turkey – fourth time in four years – trying to go back to policy normalisation. The belated admission that financial wizardry and repression do not substitute for sane monetary policy is welcome. But building central bank credibility, increasing foreign exchange reserves, and lifting the lid on a repressed financial system is not easy. Turkey is still trying to gently ease itself away from exchange-protected deposits, with limited success so far. The lira, despite policy rate hikes of 2,650 basis points, continues to depreciate and inflation is 60%.

Neo-Fisherian disinflation is perhaps possible but lowering the expected path of inflation – in effect, credibly lowering the inflation target – is a key component of that mechanism. Indiscriminately keeping interest rates low will likely fail to achieve that goal and end up convincing the public that the central bank is unable to respond to inflation. The result is what Turkey lived through in the past decade.

Going back to the observation we made at the beginning of this column, Poland also had a taste of the Turkish experience in the immediate aftermath of the ill-advised rate cut when the zloty deeply depreciated (McDougall and Martin 2023). When it comes to weak monetary policy, neither this time nor this place is different.

References

Benati, L (2023), “The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation Reconsidered”, Working paper.

Gürkaynak, R S, B P Sack and E T Swanson (2005), “The Sensitivity of Long-Term Interest Rates to Economic News: Evidence and Implications for Macroeconomic Models”, American Economic Review 95(1): 425-436.

Gürkaynak, R S, B Kısacıkoğlu and S S Lee (2023), “Exchange rate and inflation under weak monetary policy: Turkey verifies theory”, Economic Policy.

Masciandaro, D, D Romelli and S Ugolini (2023), “When Credibility Is Not Enough: Fiscal Dominance, Monetary Policy, and Exchange Rates in Early Modern Venice”, VoxEU.org, 11 September.

McDougall, M and K Martin, (2023), “Polish zloty’s fall highlights Tricky balancing act of central banks”, Financial Times, 9 September.

Schmitt-Grohe, S and M Uribe (2022), “The Effects of Permanent Monetary Shocks on Exchange Rates and Uncovered Interest Differentials”, Journal of International Economics 135, 103560.

Uribe, M (2017), “The Neo-Fisher Effect in the United States and Japan”, NBER Working Paper No 23977.

Uribe, M (2022), “The Neo-Fisher Effect: Econometric Evidence from Empirical and Optimizing Models”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 14(3): 133-162.