Anti-cartel enforcement is the least controversial of competition-policy themes. Price fixing, market sharing and other agreements to restrict competition have obvious negative effects on welfare. Within the EU, however, industry representatives have increasingly voiced concern that the European Commission imposes excessive fines to enforce anti-cartel law – particularly since the introduction of new guidelines on fines in 2006. Fines are said to be too high, disproportionate, and liable to introduce distortions into the market, ultimately leading to higher prices for consumers. It is often argued that more lenient approaches should be followed in crisis times.

Determinants of the optimal fine

The ‘optimal fine’, defined as the minimum payment that would ensure complete deterrence, should be enough to offset the expected additional profit accruing to cartel members as a result of their illegal action, if they are caught by anti-trust authorities. Key parameters for calculating the optimal fine are therefore the price increase (cartel overcharge) and the probability of detection. The empirical evidence on cartel overcharges (see Combe and Monnier 2009 for a survey) reveals a significant diversity of price increases.1

No reliable estimate exists of the probability of detection by antitrust authorities. By definition, such an estimate would require information on cartels that have not been uncovered. What can be estimated, however, is the probability that a cartel will be detected during the course of a year, conditional on the cartel being eventually detected.2 Since not all cartels are detected, economic theory suggests that the fine should be inversely correlated to the probability of detection (Bebchuk and Kaplow 1992). A 15% detection rate would suggest fines 6.7 times higher than the expected gains yielded by the cartel.

Trends in European Commission fining policy

The think tank Bruegel has recently published a paper on collusion and fines in Europe.3 The analysis is based on final decisions on cartels adopted by the European Commission between 2001 and 2012, for a total of 73 cartels and 479 convicted companies.4

Since January 2001, the European Commission has imposed fines totalling €18.4 billion on companies that have engaged in cartel activity with effects on the European Economic Area (EEA). However, relative to the potential harm that cartels could cause the European economy, €18.4 billion appears extraordinarily low. Fines account for a tiny proportion of the turnover of affected markets. Simple estimates suggest that the total affected EEA sales for the periods during which the sanctioned cartels were active could amount to roughly €209 billion.5

Figure 1 below describes trends in the Commission’s fining policy. Total and average fines since the introduction of the new fining policy in 2006 appear systematically higher. This seems to support the claim that the Commission’s fining policy has become tougher, which may help explain the outburst of discontent from industry representatives. The perception that the nominal price paid by cartel members is higher than it was in the past is confirmed by the data. However, this analysis does not yet take into account the significance of the respective cartels.

Figure 1. Fines levied on cartels by the European Commission, 2001-12

Source: Bruegel.

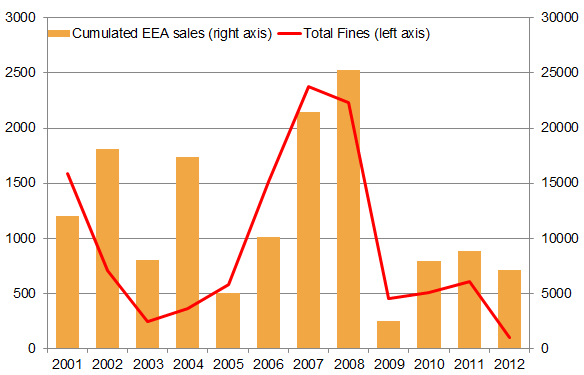

Figure 2 below provides an insight into the significance of cartels. It concerns only cartels for which EEA sales information was publicly disclosed in the decision (70% of the sample). The columns report estimates of the cumulated value of total EEA sales affected by cartels during the whole cartelised period. The red line shows the total aggregate fines for those cartels. The figure clearly suggests that after the introduction of the 2006 guidelines, there was a change in the Commission’s fining policy consistent with the aim of the new guidelines – a link between cartel members’ potential profits and the fine was successfully established. This was particularly evident in 2007 and 2008, when the value of affected markets was especially high.6 Therefore, rather than describing the Commission’s fining policy as ‘tougher’ in recent years, one should acknowledge that more recent fines reflect the greater economic effect of cartels since 2007. These factors were not properly captured by the Commission’s fining policy prior to 2006.

Figure 2. Sales affected by cartels, 2001-12, € million

Source: Bruegel.

Note: Only cartels for which EEA market information is provided.

The effect of the crisis

Fines since the implementation of the 2006 guidelines could have been higher were it not for the economic crisis. Figure 3 below plots selected indicators of anti-cartel measures taken by the European Commission against the EU real GDP growth rate. It is easy to spot the sharp crisis-related fall in the growth rate. Panel (a) shows the trend in average per company fines – these appear strongly correlated to the economic cycle, though with a slight time lag. Panel (b) shows the increase in requests for reductions in fines due to “inability to pay” – most interestingly, this indicates that the Commission started to accept these requests only in 2008. In 2010, in the aftermath of the crisis, 45% of sanctioned undertakings asked for indulgence in view of their inability to pay. Slightly fewer than a third of the applications were ultimately successful.

The red line in Panel (c) shows the trend in the calculation of the “aggravating factors” as a proportion of the basic amount defined in step one of the process. Aggravating factors are added to the fine whenever there is reason to believe that the company behaved in a particularly harmful way. The (unweighted) average aggravating factor fluctuated between 40% and 60% up to 2008, and then dropped sharply to 15–20%. While there is no reason to believe that cartel members became less ‘nasty’ after 2008, indulgence in relation to aggravating factors might have been a way for the Commission to ‘soften’ its fines during the crisis. This is further confirmed by Panel (d) of Figure 3, which shows a continual decrease in the yearly trend in the average unweighted “starting” and “additional deterrence” values as a proportion of EEA sales.7

Figure 3. The effect of the crisis on cartel fines

Source: Bruegel.

Are fines too high?

In order to test if the fines imposed by the Commission acted as a deterrent, we focus on the subsample of decisions in which some information on EEA sales by the single company was disclosed. For each company, we estimate the total additional profits realised because of the cartel, and compare them with the size of the fine ultimately applied. Both profits and fines are compared in net present value at the point at which the cartel started. In the most conservative scenario, in 27 cases out of 63 (i.e. 43% of the sample), the fine is lower than the estimated extra profits. When slightly higher profits are estimated, fines are below the additional profits in 81% of cases.8

This result relies on specific assumptions, and the subsample of companies for which information on EEA sales is available might not be representative of the whole population of cartels. Nevertheless, the result is striking. Fines are very far from their optimal level.9 For a significant number of cartels, fines are below what would be needed to ensure deterrence, even assuming a 100% detection rate. If at the time when they were considering whether or not to enter the cartel those companies could perfectly foresee future profits and costs, they would still have found it profitable to commit the infringement, even knowing that they would ultimately be caught.10

This analysis indicates that current deterrents against cartels are insufficient, and suggests that fines should be increased. However, higher fines entail (more or less hidden) costs for society and might be difficult to implement.11

A more practical solution in the short term is for the Commission to reduce the time needed to complete cartel investigations. Currently, it takes between four and six years to see the end of a cartel proceeding after an investigation is launched. Taking into account the average cartel duration, this means that an infringer should expect to be sanctioned 10 to 20 years after making the decision to break the law. In that time, managers will change jobs or even retire, essentially reaping the benefit from the infringement without fearing any cost. Increasing resources dedicated to inquiries and cutting investigation time would reduce that risk. This would also increase corporate fines in net present value at the time of the starting of the cartel, since fines would be discounted for a shorter period of time. We estimate that halving investigation time would correspond to a 10% increase in the expected fine.12

These results should be read in the context of the discussion about cuts to the Commission’s budget. While our analysis advocates an increase in resources dedicated to investigations, it also suggests that reducing the resources currently allocated could have critical consequences in terms of reduced deterrence and, therefore, increased collusion in the European economy.

Author’s note: Excellent research assistance by Marco Antonielli and Alice Gambarin is gratefully acknowledged.

References

Baker, D I (2000), “Use of Criminal Law Remedies to Deter and Punish Cartels and Bid-Rigging”, George Washington Law Review 69: 693.

Bebchuk, L A and L Kaplow (1992), “Optimal sanctions when individuals are imperfectly informed about the probability of apprehension”, Journal of Legal Studies 21.

Bos, I and M P Schinkel (2006), “On the scope for the European Commission’s 2006 fining guidelines under the legal maximum fine”, Journal of Competition Law and Economics 2(4): 673–682.

Combe, E and C Monnier (2009), “Fines against hard core cartels in Europe: the myth of over enforcement”, Cahiers de Recherche PRISM-Sorbonne Working Paper.

Fabra, N and M Motta (2013), “Antitrust Fines in Times of Crisis”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP9290.

Harrington, J (2010), “Who Should Be the Target of Cartel Sanctions? Comment on Antitrust Sanctions”, Competition Policy International 6: 41–253.

Harrington, J (2012), “Optimal Deterrence of Competition Law Infringements”, Presentation at the conference “Deterring EU Competition Law Infringements: Are We Using the Right Sanctions?”, Brussels, 3 December.

Harrington, J E and M H Chang (2009), “Modeling the Birth and Death of Cartels with an Application to Evaluating Competition Policy”, Journal of the European Economic Association 7(6): 1400–1435.

Mariniello, M (2013) “Do European Union fines deter price-fixing?”, Bruegel Policy Brief 2013/04.

Motta, M and M Polo (2003), “Leniency programmes and cartel prosecution”, International Journal of Industrial Organization 21(3): 347–379.

Wils, W P (2006), “Optimal Antitrust Fines: Theory and Practice”, World Competition 29(2).

1 It is often considered that a 20% (for national cartels) to 30% (for international cartels) overcharge is a conservative estimate of average overcharges actually implemented.

2 Most researchers would agree that a 15% chance of detection is an approximate upper bound (Combe and Monnier 2009).

3 http://www.bruegel.org/download/parent/780-do-european-union-fines-deter-price-fixing/file/1663-do-european-union-fines-deter-price-fixing/

4 The data does not account for ex-post judicial adjustment. Re-adoption decisions were excluded from the sample.

5 Affected sales means all sales in a cartelised market. They include sales by all market players (that is, not necessarily cartel members). Projection calculated on the basis of decisions for which information on affected markets is reported. Sales are indexed to inflation and cumulated throughout the period cartels were active.

6 The high variability of cumulated EEA sales from year to year (e.g. between 2008 and 2009) can be explained by the fact that the average number of sanctioned cartels per year is low in absolute terms. Therefore even if a just one small cartel is discovered, that can reduce significantly the average size of cartels sanctioned in that year.

7 The basic amount of a fine is set by determining an initial variable amount of the fine as a percentage of up to 30% of the firm’s sales within the EEA market in the last business year of the cartel (the “starting value”). This figure is then multiplied by the number of years the infringement has lasted. Finally, a fixed component equal to 15–25% of annual EEA sales is added as a further deterrent (the “additional deterrence” value).

8 We consider two different scenarios assuming respectively: 15% and 30% price overcharge and -2 and -1 elasticity. Both scenarios assume a profit margin of 15% and a 5% discount rate. The resulting extra profits earned by the cartel are thus respectively 7.4% and 18.1% of EEA sales.

9 As explained above, according to economic theory the optimal level would be 6.7 times the additional profits yielded by the infringement, assuming a 15% detection rate.

10 This of course is without accounting for secondary costs such as reputational damages.

11 Fines might discourage pro-competitive activities – as long as the probability of mistakenly convicting an innocent company is greater than zero, companies might refrain from engaging in welfare-enhancing activities, such as forming a pro-competitive research venture or joining a trade association which would have beneficial spillovers on production (Harrington 2012). Moreover, an increase in fines is likely to have a smaller marginal impact than it might have had in the past. The higher the fine, the greater the probability that the fine reaches the institutional ceilings designed to ensure that a fine does not destabilise the financial viability of a company (Bos and Schinkel 2006). At the margin, this translates into greater profitability for longer-duration infringements. Finally, excessive fines conflict with the legal principle of proportionality (Wils 2006), and are therefore not deemed credible (in other words, they might be reduced after a judicial review).

12 The weighted average fine per undertaking during the whole period of observation in net present value at the time of the starting of the cartel is €20.3 million. The net present value would increase to €22.5 million and to €24.9 million if the investigation length were halved or set to zero, respectively.