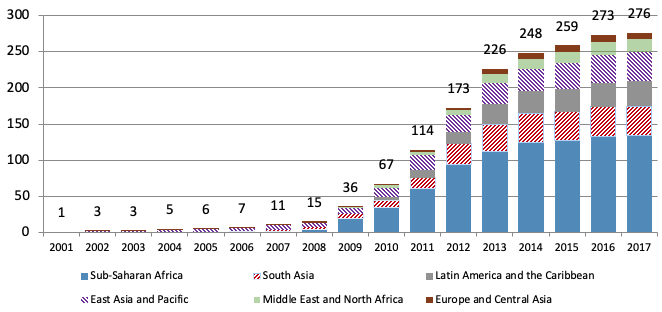

Mobile money is novel. It was barely heard of a decade ago.1 Yet it has transformed the landscape of financial inclusion in developing and emerging market countries, leapfrogging the provision of formal banking services (Figures 1 and 2). Mobile money is available in two-thirds of low-to-middle-income countries.2

Figure 1 Number of live mobile money services for the unbanked by region

Source: Data from the GSMA State of the Industry report (2017).

Notes: The first mobile money system was launched in the Philippines in 2001, and M-Pesa in 2007.

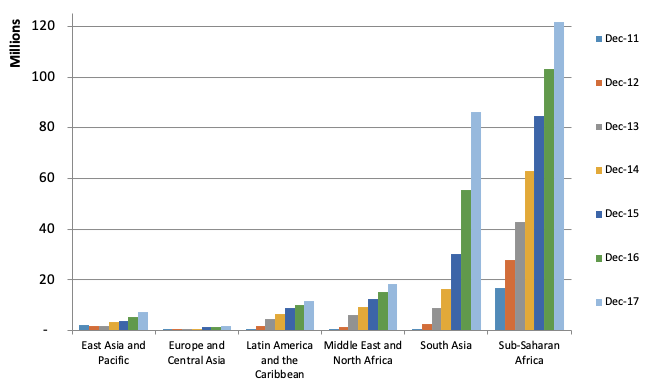

Figure 2 Growth of active (90 day) mobile money accounts by region

Source: Data from the GSMA State of the Industry report (2017).

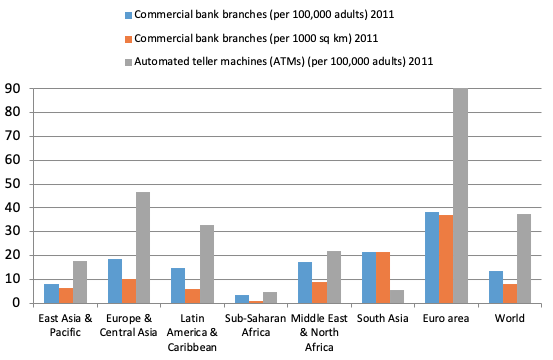

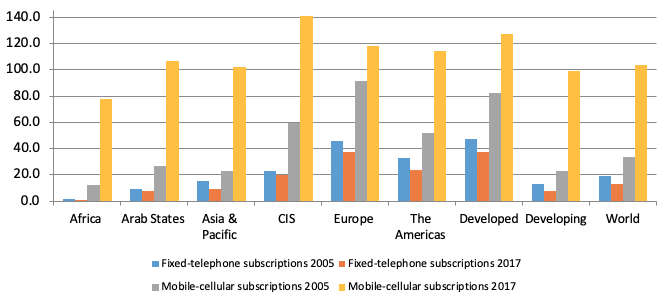

Mobile money refers to financial transaction services potentially available to anyone using a mobile phone, including the unbanked global poor who are not a profitable target for commercial banks (Figure 3). An individual installs a mobile phone application on a SIM card, establishes an electronic money account with the services provider (usually a mobile network operator alone or in formal partnership with one or more banks, depending on the national jurisdiction), and deposits cash in exchange for electronic money.3 Even tiny amounts can be stored, withdrawn as cash, or transferred via a coded secure text message to others, without the customer or recipient having a formal bank account. Mobile phone technology has the advantage that users invest in the handset, while a (scalable) infrastructure is already present for widespread distribution of airtime through secure network channels, Figure 4. By adopting mobile money, under-served citizens gain a secure means of transfer and payment at a lower cost, and safe, private storage of funds.

Figure 3 Provision of banking infrastructure

Source: Data from the G20 Financial Inclusion Indicators database, World Bank.

Notes: This shows the position in 2011 a few years after the adoption of mobile money in Kenya. The first five regions refer to “developing only”.

Figure 4 Fixed telephone and mobile-cellular subscriptions: 2005 and 2017

Source: Data from the ITU World Telecommunication, ICT Indicators database.

Notes: Subscriptions are per 100 inhabitants. “Mobile phone subscribers” refer to active SIM cards rather than individual subscribers.

The technological innovation ameliorates the asymmetric information constraint faced by conventional banks in lending to the collateral-less poor. The movement of cash into electronic accounts tracks, for the first time for the unbanked, the real-time history of their financial transactions. Using algorithms, these records provide evolving individual credit-scores that eventually allow users to obtain a pathway to formal financial services accessed only through a mobile phone, e.g. to interest-bearing savings accounts, small loans, and insurance products. Hire purchase credit is possible through mobile money, permitting secure, remote purchases of costly durable items on a pay-as-you-use basis.4

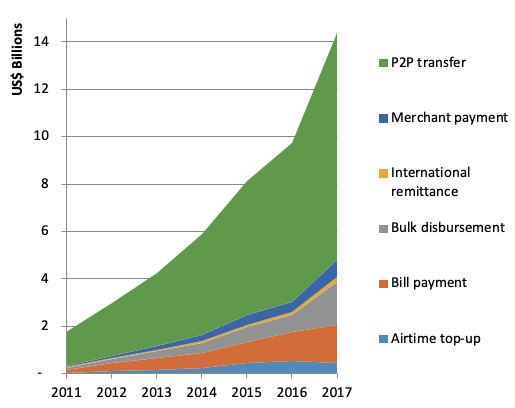

Mobile payments in economies with deep financial markets are linked with pre-existing bank accounts.5 In largely cash-based developing or emerging countries, most users are unbanked. As mobile money systems evolve, and smart-phones become affordable in poorer countries,6 services could broaden (e.g. Figure 5) and link with those managed by banks and insurance companies. At the margins, this blurs the distinctions between mobile banking and mobile money. But the poorest will remain unbanked, relying on mobile money for basic financial services.7

Figure 5 Growth of a diverse payments platform

Source: Data from the GSMA State of the Industry reports (2016 and 2017).

Note: Bulk payments include salary and pension payments, and government or NGO transfers.

With the novelty and rapid growth of mobile money systems, the regulatory response has been caught off-balance. The regulatory environment shapes the viability and variety of business models, competition and innovation. Mobile money is big business, but ironically, it is not easily profitable (Aron 2017).8 Evidence suggests that enabling regulation promotes the profitability and sustainability of mobile money systems.9 Critical regulatory lessons are summarised by Aron (2019), Di Castri (2013) and Klein and Mayer (2011).

The economics of mobile money: The micro view

Mobile money potentially helps ameliorate several areas of market failure in developing economies.10

Lower transactions costs

Transactions costs are reduced for sending and receiving money, especially with inadequate transport infrastructure. These include the transport costs of travel; the travel time and the waiting time in long queues; coordination costs between individuals, between firms and suppliers or customers, and between government and individuals; and costs of delays and leakages acting like a tax (or complete loss through theft from insecure methods of money transfer).

Improved transparency

The impact of enhancing transparency through electronic records is far-reaching. Every deposit, withdrawal, transfer or payment transaction through mobile money creates a recorded financial history. This protects customers’ rights and fosters trust in business, promoting the growth of efficient payments networks. Mobile money makes international remittances more affordable and traceable. Tax collection could be improved through mobile payment, and avoidance reduced through more visible spending. Mature mobile money systems foster the formalisation of the economy, integrating informal sector users into business networks, formal banking and insurance, and linking to government through social security, tax, and secure wages payments.

Saving

Mobile money alters the nature of saving and increases saving through digital means. For the unbanked poor, their ‘immersion in physical cash creates considerable frictions in their financial lives’ (Radcliffe and Voorhies 2012). Cash-based households save informally with risk of theft, e.g. cash under the mattress; accumulation of assets such as jewellery or livestock; and saving via informal savings groups. Mobile money electronic accounts safely store cash, though without paying interest, and offer possibilities for commitment savings accounts (Dupas and Robinson 2013), encouraging saving by the poor.

Privacy and empowerment of women

Women or minority groups often face limitations in opportunities and access to property, an aspect of inequality that can produce widespread economic inefficiencies. Mobile money can alter bargaining power within the family, empowering female mobile money users. Greater privacy may influence both inter-household allocations (Jakiela and Ozier 2016) and intra-household allocations (Duflo and Udry 2004). Compared with cash receipts, the reduced observability of the timing and sizes of mobile transfers and the accumulated electronic balances, could protect savings for the recipient.

Risk and insurance

Living standards of the poor are at risk of communal shocks including pestilence, other natural disasters, conflict and medical epidemics; and idiosyncratic shocks including theft, damage to the homestead, illness and death. Formal insurance is typically absent, but family, clan and network ties can create informal insurance networks, monitored by trust relationships within the network (De Weerdt and Dercon 2006). Jack and Suri (2011) suggest how mobile money can facilitate risk-spreading. The geographic reach of networks can enlarge. Timely transfers of even small amounts of money can arrest serious declines otherwise hard to reverse. More efficient investment decisions can be made, improving the risk and return trade‐off. Mature mobile money systems allowing access to micro-insurance provide an additional buffer.

Expanding network and labour market opportunities

Mobile money could alter the size and cohesion of social networks. Improved risk-sharing and cheaper, long-range remittances expand the scope of labour decisions to higher-risk but higher-return occupations, or migration to higher-return labour markets (Suri and Jack 2016). Reduced transactions costs of remittances might foster more liberal attitudes to migration from the homestead (Jack and Suri 2011), though distant migrants are less observable and accountable. There is huge scope for research on network formation or dissolution, and on migration and remittance decisions, using mobile money transactions data (Chuang and Schechter 2015).

Empirical evidence from the micro literature

Demonstrating welfare and risk-sharing gains from mobile money across countries could bolster the case for government and donor support, and investment. A burgeoning microeconomic empirical literature has attempted to quantify the economic gains of access to secure financial services through mobile money, and factors driving the adoption of mobile money. However, this literature is burdened by problems with data, methodology, and identification.

Data challenges

Institutional and political regime changes affect the uptake of mobile money. In Côte d’Ivoire, for example, the cessation of conflict from 2012 was key to mobile money adoption (Pénicaud and Katakam 2014). Shifts occur over time in the relevance of determinants, e.g. cheaper, more capable smartphones widen access and ownership. In principle, one could test empirically for the effects of shifts and regime changes.

Empirical regressions will be mis-specified when omitting hard-to-measure variables linked to mobile money, such as spillover learning effects in the community, and technological and quality changes. Important observables, such as education quality and wealth, are typically poorly measured, which may exacerbate the biases. Definitional ambiguities can introduce measurement bias in mobile money usage.11 However, if privacy concerns can be overcome, new access to a rich seam of big data, the administrative mobile money transactions from business and individuals, presents an enormous research opportunity.12

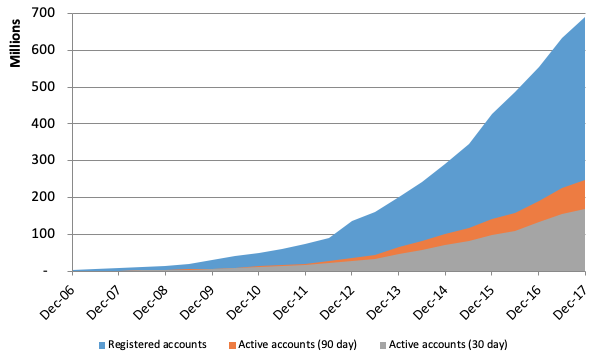

Figure 6 Registered and active total accounts

Source: Data from the GSMA State of the Industry report (2017).

Note: This figure shows that of the 690,000 registered accounts in December 2017, only 168,000 were 30 day active (i.e. at least one transaction was performed in the preceding 30 days).

Challenges for empirical methods

The quantitative empirical work encompasses studies assessing the determinants of the adoption of mobile money (i.e. a proxy for usage of mobile money is the dependent variable), and studies of the effects of mobile money on microeconomic outcomes. Examples of the latter include whether mobile money promotes improved risk-sharing, food security, consumption, business profitability, saving and effective use of cash transfers.

Two selection problems are faced, raising the problem of ambiguous causality.13 The roll-out of mobile money by operators and their agents may not be random if they choose areas to operate in based on household and village characteristics. For instance, if wealth determines agent selection into a village (and wealth is not properly controlled for in regressions) this will exaggerate the effect of mobile money in promoting consumption. It is difficult to disprove self-selection by the agents toward more profitable locations.14 A second selection problem is undisputed: adoption of mobile money by individuals is influenced by factors both observable (e.g. education, urban dwelling and the use of banking services) and unobservable (e.g. susceptibility to risk, community learning spill-over effects and changes in technology preference) that may also be correlated with mobile money use. Thus, it is difficult to establish one-way causality using measures of usage of mobile money.

The dominant empirical methodologies in this field are randomised controlled trials (RCT),15 quasi-experiments with a difference-in-differences estimation strategy or the non-parametric method of propensity score matching, and instrumental variables. The methods have differing degrees of success in dealing with heterogeneity16 at the individual or household level. Another consideration is whether results can be “scaled-up” or “transported” to generalise to other contexts with different institutional structures.

Assessing the evidence

A detailed, technical survey of a range of studies is presented in Aron (2017, 2018). The best of these studies exploits panel data. Amongst the most convincing analyses are the difference-in-differences analyses demonstrating how mobile money has fostered risk-sharing amongst informal networks after large shocks. The proposed mechanism stems from the reduced transaction costs. The focus is not on the direct effect of mobile money usage on welfare, but on how mobile money usage interacts with a negative income shock (e.g. a drought or flood), while controlling for household characteristics.17 In Kenya, Jack and Suri (2014) find total consumption of mobile money users is unaffected by negative income shocks while consumption drops for non-users, especially the poorest. For Tanzania, Riley (2018) further examines the potential beneficial spillover effects of mobile money to the rural village community following a negative shock.

The Ugandan rural panel study of Munyegera and Matsumoto (2016a) supports qualitative evidence that education and wealth influence adoption. Several studies claim the beneficial influence of mobile money on reported savings (by saving method), and on saving flows (Demombynes and Thegeya (2012), Munyegera and Matsumoto (2016a), and Mbiti and Weil (2016)). However, the results are compromised by problems of ambiguous causality, and no robust and conclusive results can be reached. RCT studies in Mozambique and Afghanistan (Batista and Vicente 2016, Blumenstock et al. 2015b) suggest saving did not increase though saving methods switched to mobile money; these studies use small and specialised samples and are probably not generalisable.

Far less satisfactory are several (non-RCT) welfare studies reviewed, where results are generally judged unreliable by Aron (2018). Problems of ambiguous causality for the mobile money usage dummy are centre-stage, and the use of various methods18 to mitigate this are not always convincing. Two stronger studies are for Uganda (Munyegera and Matsumoto 2016a) and Kenya (Suri and Jack 2016). The Kenyan panel study suggests consumption growth for female-headed households was positive with access to mobile money, with occupational shifts out of farming, and 2% of Kenyan households were lifted out of poverty. But the result is tempered by probable bias, see Aron (2018).19

A convincing RCT welfare study by Aker et al. (2016) finds household welfare improved after drought for recipients of cash transfers through mobile money accounts in Niger. Intra-household bargaining power for women was promoted20 and their productivity improved by reduced transport costs, travelling and queuing time. Recipients were more likely to cultivate and market cash crops, and child diets improved. To reap such benefits, the mobile money infrastructure must be functional. Generalisability awaits replication across other locations, cultures, continents and time periods.

Final thoughts

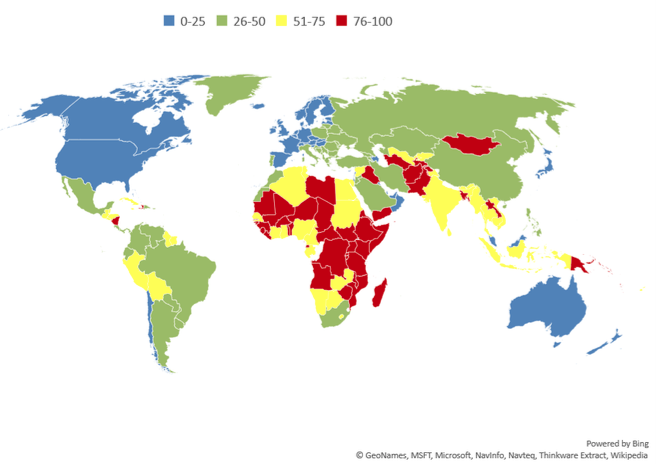

Atkinson (2015) argued that economic inequality is often aligned with differences in access to, use of, or knowledge of information and communication technologies (e.g. Figure 7). He stressed that researchers, firms, policymakers and governments have the possibility to shape the direction and path of technological change. Aid agencies, donors and international agencies have strongly fostered the beneficial growth of mobile money and financial inclusion.

Figure 7 The percentage of people NOT using the internet in 2016

Source: Constructed using data from the ITU World Telecommunication, ICT Indicators database.

Static, micro-data-based snapshots are liable to understate the system-wide benefits of mobile money. Micro-analysis misses the positive externalities linked to network growth and increased transparency and formalisation of the economy. The static analysis misses the likelihood that many benefits take time to accumulate even at the individual level, so the long-term benefits are likely to be greater.

References

Aker, J C and J E Blumenstock (2015), “The Economics of New Technologies in Africa”, in C Monga and J Yifu Lin (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Africa and Economics. Volume 2: Policies and Practices, OUP.

Aker, J C, R Boumnijel, A McClelland, and N Tierney (2016), “Payment Mechanisms and Anti-Poverty Programs: Evidence from a Mobile Money Cash Transfer Experiment in Niger”, Economic Development and Cultural Change 65(1): 1-37.

Aron, J and J Muellbauer (2019), “The Economics of Mobile Money: harnessing the transformative power of technology to benefit the global poor”, Oxford Martin School Policy Paper.

Aron, J (2018) "Mobile Money and the Economy: A Review of the Evidence“, World Bank Research Observer 33 (2):135–188.

Aron, J (2017), “‘Leapfrogging’: a Survey of the Nature and Economic Implications of Mobile Money“, CSAE Working Paper 2017-2, Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford.

Atkinson, A B (2015), Inequality: What can be done?, Harvard University Press.

Batista, C and P C Vicente. (2016), “Introducing Mobile Money in Rural Mozambique: Evidence from a Field Experiment“, CSAE Conference 2016: Economic Development in Africa, Oxford

Blumenstock, J (2012), “Inferring patterns of internal migration from mobile phone call records: evidence from Rwanda”, Information Technology for Development 18(2): 107-125.

Blumenstock, J E, G Cadamuro and R On (2015a), “Predicting poverty and wealth from mobile phone metadata”, Science 350(6264): 1073-1076.

Blumenstock, J E, M Callen, T Ghani, and L Koepke (2015b), “Promises and Pitfalls of Mobile Money in Afghanistan: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial”, The 7th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (ICTD '15), Singapore.

Chuang, Y and L Schechter. (2015), “Social Networks in Developing Countries”, Annual Review of Resource Economics 7: 451-472.

De Weerdt, J, and S Dercon (2006), “Risk-Sharing Networks and Insurance Against Illness”, Journal of Development Economics 81(2): 337–56.

Deaton, A and N Cartwright. (2016), “Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials“, NBER Working Paper No. 22595 (also see the Vox column here).

Demombynes, G and A Thegeya. (2012), “Kenya’s Mobile Revolution and the Promise of Mobile Savings”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 5988.

di Castri, S (2013), “Mobile Money: Enabling regulatory solutions”, GSMA, February.

Duflo, E and C Udry (2004), "Intrahousehold Resource Allocation in Cote d'Ivoire: Social Norms, Separate Accounts and Consumption Choices”, NBER Working Paper 10498.

Dupas, P and J Robinson (2013), “Why Don’t the Poor Save More? Evidence from Health Savings Experiments”, American Economic Review 103(4): 1138–1171.

Federal Reserve (2016), Survey of Consumers and Mobile Financial Services 2016, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, March.

GSMA (2016), “State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money: Decade Edition: 2006-2016”, www.gsma.com/mobilemoney

GSMA (2017), “The Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa 2017”, GSM Association. www.gsmaintelligence.com

Jack, W, and T Suri (2011), “Mobile Money: The Economics of M-Pesa”, NBER Working Paper 16721.

Jack, W, and T Suri (2014), “Risk Sharing and Transactions Costs: Evidence from Kenya’s Mobile Money Revolution”, American Economic Review 104(1): 183–223.

Jakiela, P and O Ozier, (2016), "Does Africa Need a Rotten Kin Theorem? Experimental Evidence from Village Economies”, Review of Economic Studies 83(1): 231-268.

Klein, M and C Mayer. (2011), “Mobile Banking and Financial Inclusion: the Regulatory Lessons”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5664.

Mbiti, I and D N Weil, (2016), “Mobile Banking: The Impact of M-Pesa in Kenya,” in S Edwards, S Johnson and D Weil (eds), African Successes: Modernization and Development, University of Chicago Press.

Munyegera, G K and T Matsumoto (2016a), "Mobile Money, Remittances, and Household Welfare: Panel Evidence from Rural Uganda," World Development 79: 127-137.

Munyegera, G K and T Matsumoto (2016b), “Banking on the Cell-phone: Mobile Money and the Financial Behaviour of Rural Households in Uganda“, CSAE Conference 2016: Economic Development in Africa, Oxford

Pénicaud, C and A Katakam (2014), State of the Industry 2013, GSMA Mobile Financial Services for the Unbanked, GSMA.

Radcliffe, D and R Voorhies. (2012), “A Digital Pathway to Financial Inclusion”.

Riley, E (2018), “Mobile Money and Risk Sharing Against Aggregate Shocks”, Journal of Development Economics 135: 43–58.

Suri, T and W Jack (2016), “The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money”, Science 354(6317): 1288-1292.

Endnotes

[1] The rapid growth since 2007 of Kenya’s M-Pesa system (“M” is for mobile, and “pesa” is Swahili for money) through Safaricom, a subsidiary of Vodafone, has brought mobile money to international prominence.

[2] Vodafone alone exported the M-Pesa system to Afghanistan (2008), to India (2013), to Europe (Romania in 2014 and Albania in 2015), and to many countries in Africa. In Romania, over a third of the population had no access to conventional banking, and seven million people mainly used cash, see Africa’s digital money heads to Europe (Financial Times, 30th March 2014).

[3] Money is deposited into the account by giving cash to an agent, in return for electronic money via the mobile phone. To withdraw money, electronic money is transferred via the mobile phone to the agent’s electronic money account and cash is received in return. Depositors do not receive interest on their electronic accounts and bear the risk of loss of value through inflation.

[4] For example, affordable solar energy-powered electricity systems in rural areas can be fully purchased remotely on a pay-as-you-use basis using mobile payments (e.g. M-Kopa Solar launched in 2014 in Kenya).

[5] In China, 80% of Chinese have at least one bank account (Global Findex data for 2017), and mobile payments providers like Alipay and WeChat Pay have leveraged the existing banking infrastructure.

[6] Smartphones below US$100 from Asian manufacturers are now commonplace and recycled smartphone markets are burgeoning (GSMA 2017).

[7] Even in advanced countries, the proportion of the under-banked and unbanked can be significant, with the unbanked deterred from opening bank accounts by minimum balance requirements and fees. Unbanked consumers comprise 9% (over 25 million adults) and under-banked consumers, 22%, of all US consumers (Federal Reserve, 2016); the under-banked possess, but do not use, a bank account.

[8] The benchmark to break even and show profit is about a million active subscribers, each performing at least one transaction per month. For accounts that are active on a 90-day basis, data from GSMA (2016) reveal that Kenya’s M-Pesa was the first to break even in 2008, but that by 2016, only 35 of the global services in Figure 1 had reached “critical mass” (half of these being in SSA).

[9] Some countries had stringent protective restrictions in the early stages, stultifying growth and innovation, and creating barriers to entry (e.g. India). Others, notably Kenya, initially adopted a light-touch regulation and then adapted and tightened regulation over time as markets grew.

[10] See Karlan et al. (2016) on market failure in a more general context of financial services.

[11] Using the number of mobile money accounts or the number of registered customers may induce multiple counting of the same individual if several accounts are held with different providers. If registered customers are inactive (and globally two-thirds of registered accounts are inactive with a generous 90-day definition), this will exaggerate the true participation, see Figure 6. Where unregistered customers intensively use the service, as in over-the-counter services, overall usage will be under-estimated.

[12] Mobile money payments data could be used to help forecast hard-to-gauge household assets and expenditure that otherwise rely on self-reported data (Blumenstock et al., 2015a), to derive proxies for migration patterns from geotagged data (Blumenstock, 2012) and explore social networks, relevant for work on remittances (Aker and Blumenstock, 2015).

[13] Technically, this is an ‘endogeneity problem’, which in econometrics occurs when an explanatory variable is correlated with the error term, because of simultaneous causality, omitted variables and/or measurement error. There are several statistical methods that aim to correct the resulting bias in the regression estimates.

[14] Several authors contend there is little statistical correlation between agent “roll-out” and household observable characteristics that might have been associated with future outcomes; but they use partial (one at a time) correlates only, which are not decisive (for a critical discussion, see Aron (2018)).

[15] See also Deaton and Cartwright (2016).

[16] Heterogeneity refers to the variation across surveyed individuals, some of which can be observed and controlled for (e.g. individuals differing by age and education), but some of which is difficult to measure (e.g. the changing technological preferences of individuals). Thus, omitted heterogeneity is an omitted variable, and hence a kind of endogeneity.

[17] The best of these studies exploits the properties of panel data to remove sources of unobserved time-invariant household heterogeneity using household fixed effects, include location-by-time dummies and rural-by-time dummies to help control for time-varying heterogeneity and include appropriate controls for household characteristics.

[18] Poor instrumentation and a lack of balanced panel data are problems here.

[19] This study is at its most convincing in the differenced specification for consumption; but even there, bias arises from the limited control of heterogeneity (Aron 2018).

[20] Cash-transfer recipients were able temporarily to conceal the arrival of the transfer.