Until recently, liquidity risk was not the main focus of banking regulators. However, the 2007–2009 crisis showed how rapidly market conditions can change, exposing severe liquidity risks for some institutions. Although capital buffers were effective in reducing liquidity stress to some extent, they were not always sufficient. In the light of this, efforts are underway internationally as well as in individual countries to establish or reform existing liquidity risk frameworks – most notably the proposals by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS 2013). The European Systemic Risk Board has recently recommended that national supervisory agencies intensify the supervision of liquidity and funding risks as well (ESRB 2012).

Despite these significant regulatory efforts, little is known about the fundamental factors which determine banks’ incentives to hold liquid assets in their portfolios, and whether these determinants are affected by liquidity regulation (see Delechat et al. 2012 for a recent IMF study analysing a similar question for just Central America). This column presents the results of our recent working paper in which we undertake the first global analysis of the determinants of banks’ liquidity holdings and the role of liquidity regulation (Bonner et al. 2013).

While we take into account bank-specific, macroeconomic and financial development factors, we are particularly interested in the impact of banks’ operating environment – namely the strength of existing deposit insurance systems, the concentration of the banking sector, and banks’ disclosure practices.

Contextual factors

Based on our reading of the academic literature, we identify three macro factors which influence banks’ liquidity holdings.

- First, a higher degree of bank concentration implies greater systemic importance for each bank within the economy and thus lower liquidity buffers.

Higher concentration increases the probability that any individual bank will receive public support should it become distressed. In other words, it reduces the effective liquidity risk faced by each individual institution thanks to a larger (implicit) public guarantee. Consequently, we would expect a more concentrated banking sector to be associated with lower liquidity buffers.

- Second, the banking literature frequently associates higher disclosure requirements with greater market discipline and thus higher liquidity buffers.

Greater transparency allows market participants to price firms’ strategies more accurately, and thus to reduce socially excessive risk-taking by financial institutions. In a market environment characterised by low transparency, financial institutions may find it profitable to adopt riskier strategies at the expense of uninformed customers or investors. By similar reasoning, we expect a bank that is subject to low disclosure requirements to manage liquidity risk less prudently, thus reducing the size of its liquidity buffer.

- Third, the reliability and coverage of the deposit insurance system is expected to lower banks’ liquidity risk exposure, and hence their liquidity buffers.

Ceteris paribus, increasing deposit insurance coverage should reduce the likelihood of bank runs – an extreme form of liquidity shock. On the other hand, deposit insurance schemes in most jurisdictions are (at least partially) funded by the banking sector. Such a funding structure is likely to exert market discipline, as the individual institutions have more incentives to conduct peer monitoring. Hence, independent of liquidity regulation, the net effect of deposit insurance is an empirical question – it either lowers liquidity buffers as it reduces liquidity risks, or it increases liquidity buffers due to increased market discipline.

Determinants of banks’ liquidity holdings

For our analysis, we collected annual balance sheet data for all banks in the BankScope database from 1998 until 2007 for 30 OECD countries. We choose the start and end date of the sample so as to capture the period before the global financial crisis which started in mid-2007. By considering this period, we reduce the risk of unobserved underlying heterogeneity in domestic banking regulation across OECD countries (being harmonised by Basel I) when we analyse banks’ liquidity management in ‘normal’ times.

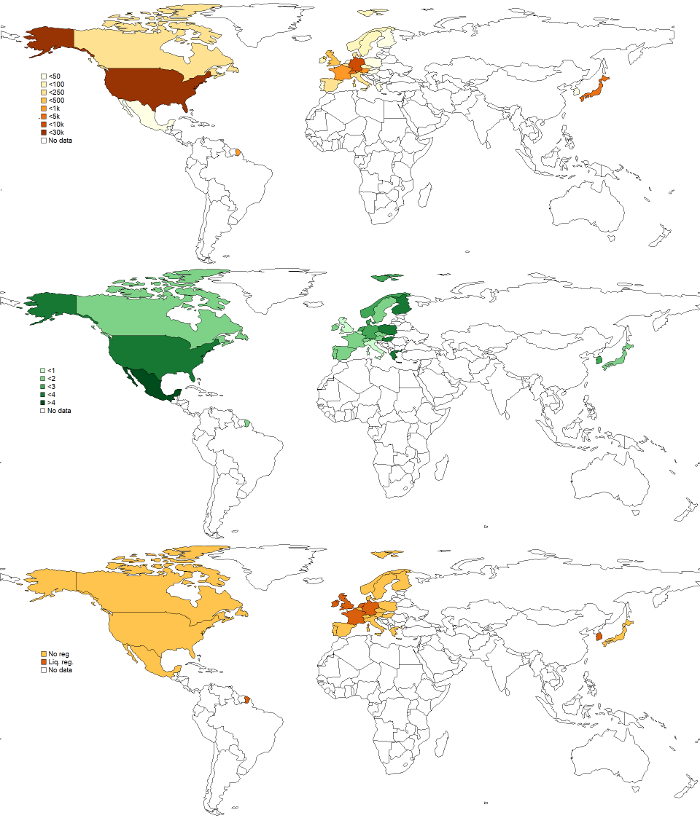

Figure 1 below shows a) the geographic location of our observations; b) the average holdings of liquidity per country; and c) whether a liquidity requirement is in place.

Figure 1. Countries included in the sample

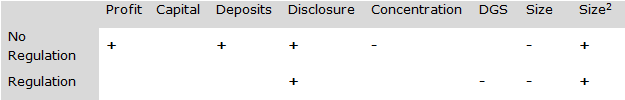

Our analysis reveals that without liquidity regulation, banks’ liquidity buffers are determined by a combination of bank- (business model, profitability, deposit holdings, and size) and country-specific (disclosure requirements, concentration of the banking sector) factors. We regress liquidity buffers on these factors both for the full sample and sample splits for countries with and without liquidity regulation (and, additionally, a wide range of sensitivity tests). As most factors turn insignificant with a liquidity requirement in place, we conclude that regulation substitutes for most determinants of liquidity holdings. A bank’s disclosure requirement, on the other hand, complements liquidity regulation. Our results further suggest a non-linear relationship between size and banks’ liquidity holdings, with the very largest institutions holding relatively more liquidity.

Table 1. Signs of the explanatory variables (dependent variable is liquidity holdings)

Note: Empty cells denote non-significant coefficients.

Policy implications and conclusion

New liquidity regulation is currently being put in place. We have shown the determinants of buffers held by commercial banks. The complementary features of disclosure and liquidity requirements provide strong incentives for regulators to jointly harmonise disclosure and Basel III liquidity requirements across countries.

References

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2013), “Basel III: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and liquidity risk monitoring tools”.

Bonner, C, I Van Lelyveld, and R Zymek (2013), “Banks’ Liquidity Buffers and the Role of Liquidity Regulation”, DNB Working Paper 393.

Delechat, C, C Henao, P Muthoora, and S Vtyurina (2012), “The Determinants of Banks’ Liquidity Buffers in Central America”, IMF Working Paper 12/301.

European Systemic Risk Board (2012), “Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board of December 2012 on funding of credit institutions” (ESRB/2012/2) (2013/C 119/01).