After some years under the radar, the debate over reducing weekly working hours has returned in force in several OECD countries (Gomes 2021, OECD 2022). Pilot experiments testing a shorter work week, mostly based on voluntary participation by firms, are taking place in Portugal (Portugal News 2022) and Spain (Kassam 2021). The first results of an on-going trial in the UK seem positive (Gross 2022); the same in Ireland (4 Day Week Global 2022). The private sector has taken some independent initiatives too.

Better job quality and work-life balance are at the forefront of the debate on shorter working hours, but this has not always been the case: in the past decades, much of the debate about shorter hours has been to create jobs by redistributing available work. “As long as there is one man who seeks employment and cannot find it, the hours of work are too long”, said Samuel Gompers, an American labour leader at the end of the 19th century. In France, 20 years after the introduction of the 35-hour work week, the debate still revolves around how many jobs were created thanks to the reform (Poingt 2018).

Empirically, the debate about how shorter hours (usually at constant salaries) affect employment has never really been closed. The idea that a shorter work week could lead to higher overall employment is just a variation of the ‘lump-of-labour’ fallacy – the assumption that there is a fixed amount of work to be done – which is very hard to eliminate from the public debate, as discussions on immigration, pensions, or technology often show.

In a recent article (Batut et al. 2022), we study the reforms that took place in Europe at the turn of the millennium (Portugal in 1996, Italy in 1997, France in 1998, Belgium in 2001, and Slovenia in 2002) under the umbrella of the EU Working Time Directive. These reforms did not reduce the days worked, as most proposals these days, but rather reduced the hours worked in the day. Nevertheless, they can provide some useful pointers for current discussions.

To identify the causal effect of reductions in working time on employment and other outcomes (hours of work are not random but carefully chosen by companies and, sometimes, workers), we use the initial variation in the share of workers exposed to the reforms across sectors (some sectors were already working fewer hours than what the reforms required and were therefore not affected by the legislative change). This strategy makes it possible to assess variation across several reforms in similar contexts over a short period and arrive at an average impact of multiple legislative changes, net of national and sectoral trends.

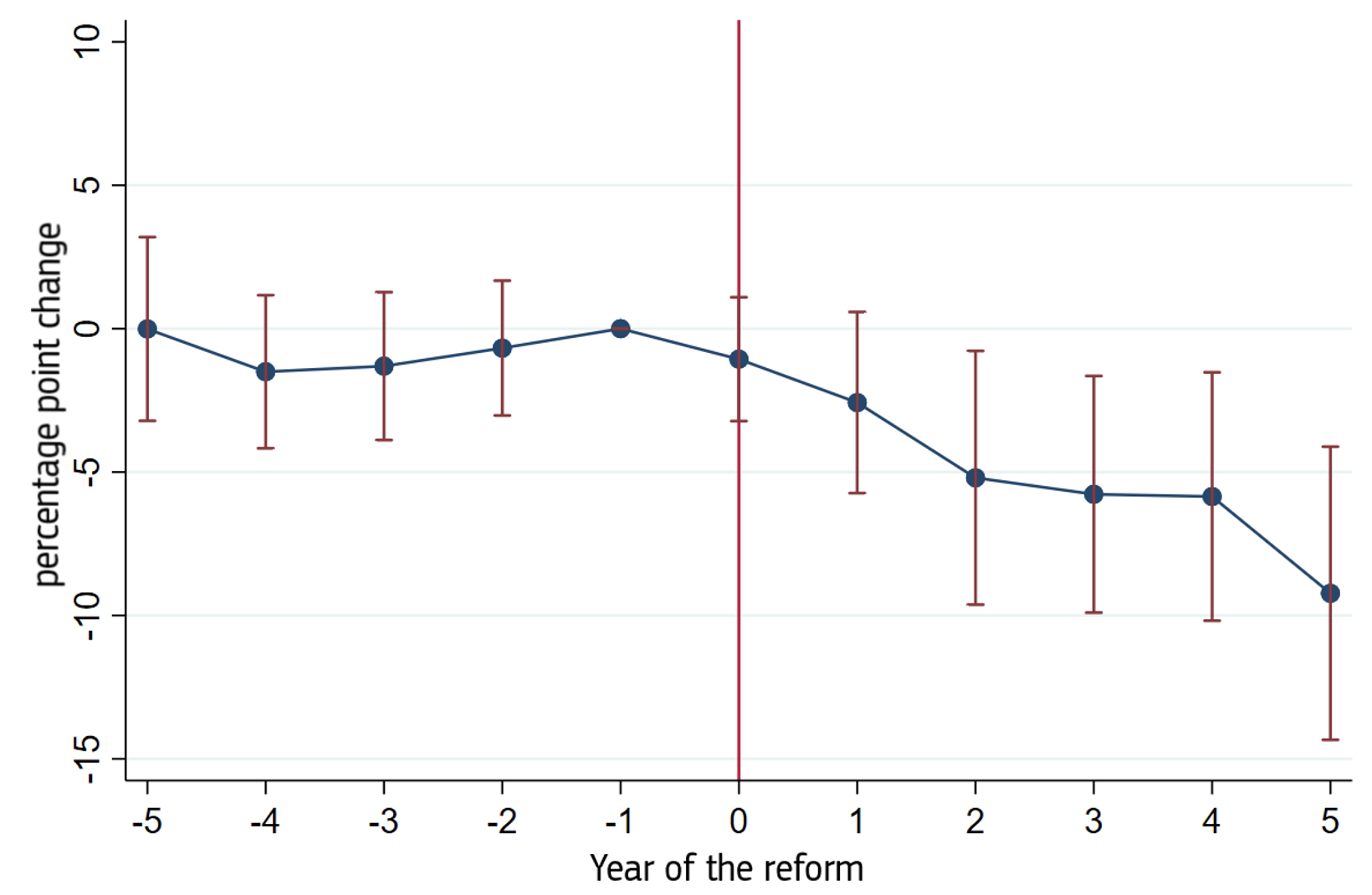

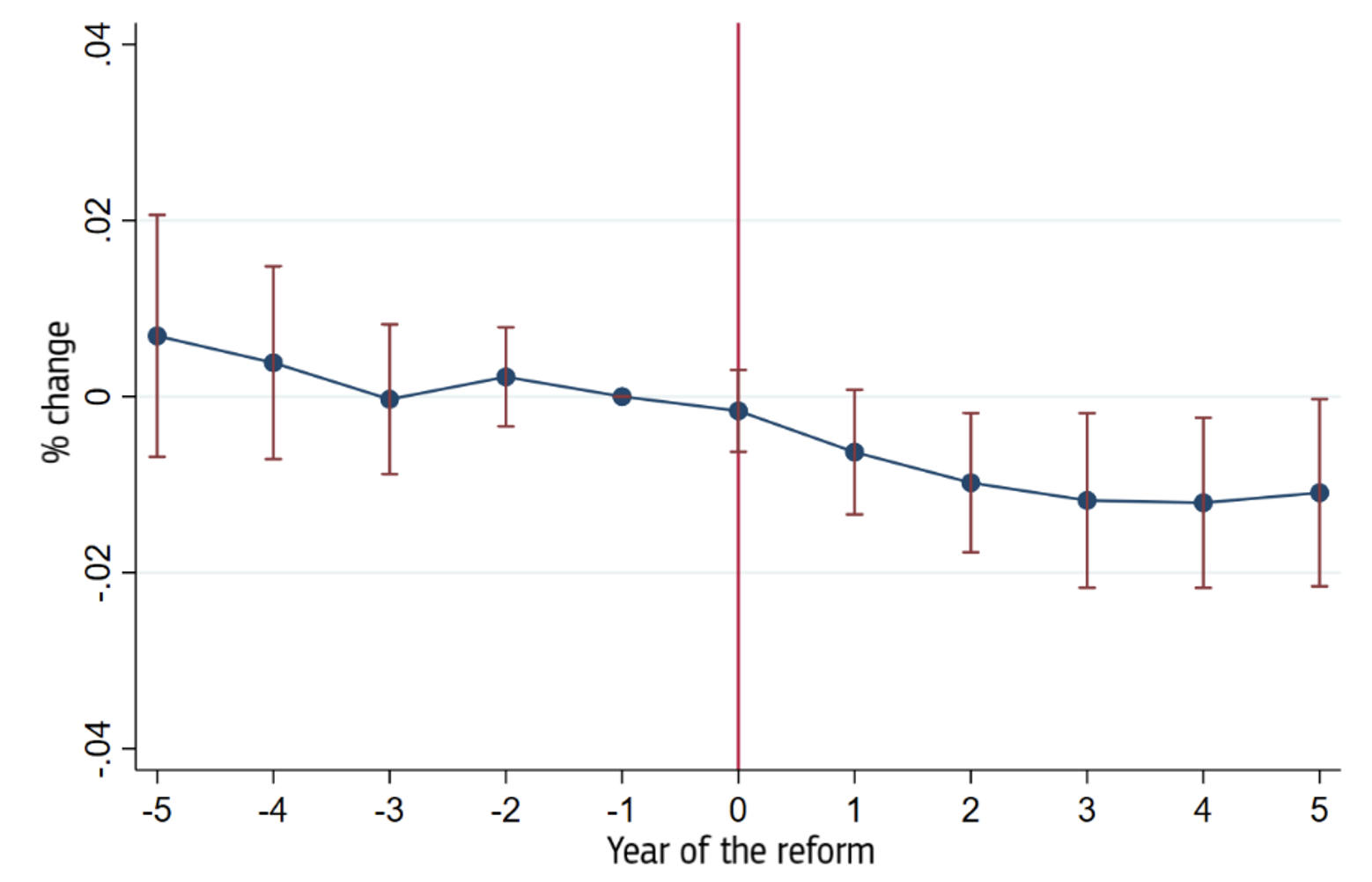

Our analysis shows that, on average and relative to sectors where weekly working hours were already below the median, the reforms reduced the share of workers with usual weekly hours above the threshold and the yearly hours worked per employee (Figure 1). This may seem an obvious result but it is not, because firms could have simply resorted to overtime work or other ways to maintain hours worked per employee. The reforms did lead to a reduction in hours worked.

Figure 1 The effect of reductions in working time

(A) Effect on the share of workers working more hours than the new weekly threshold

(B) Effect on the hours worked per employee

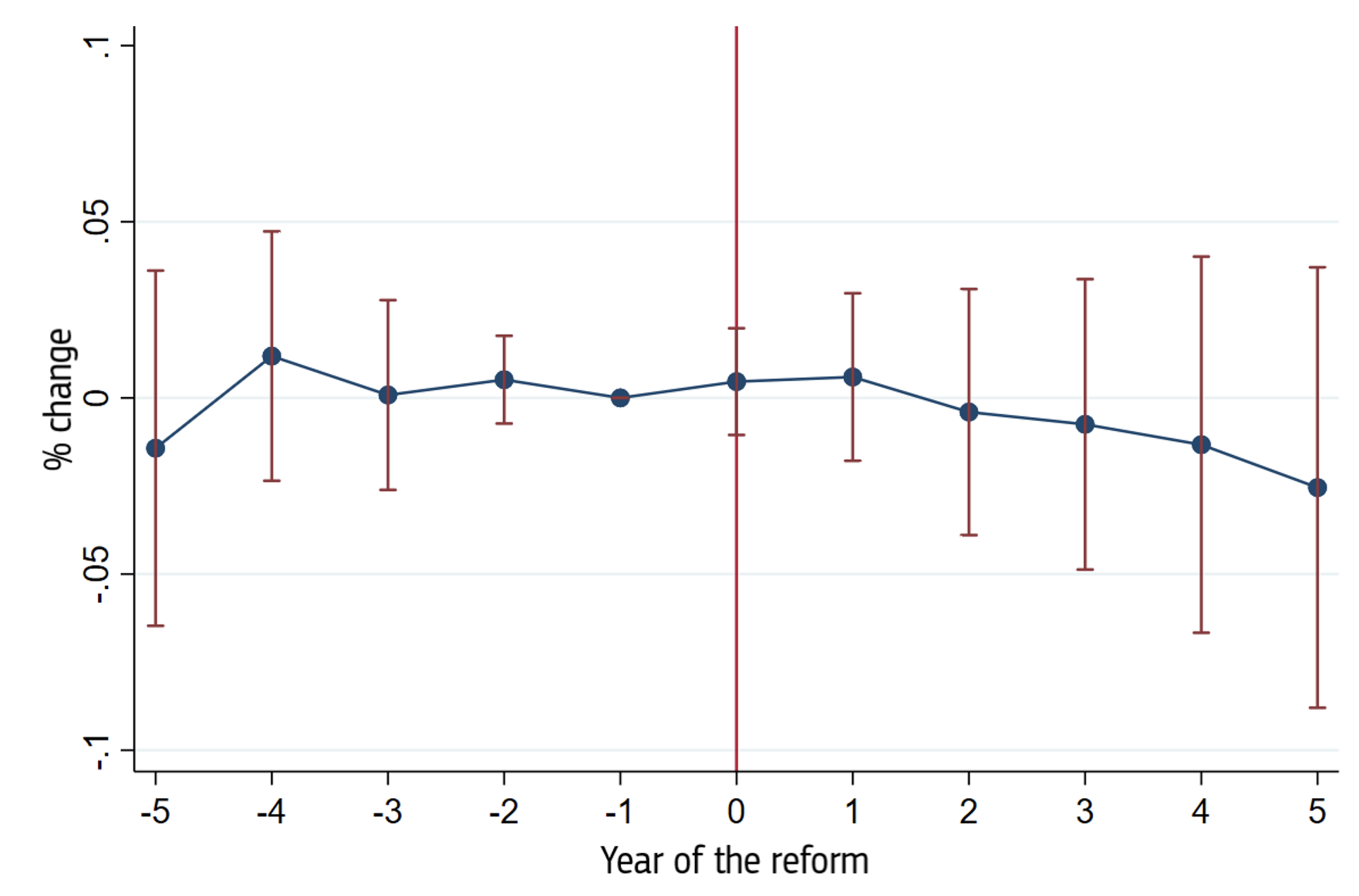

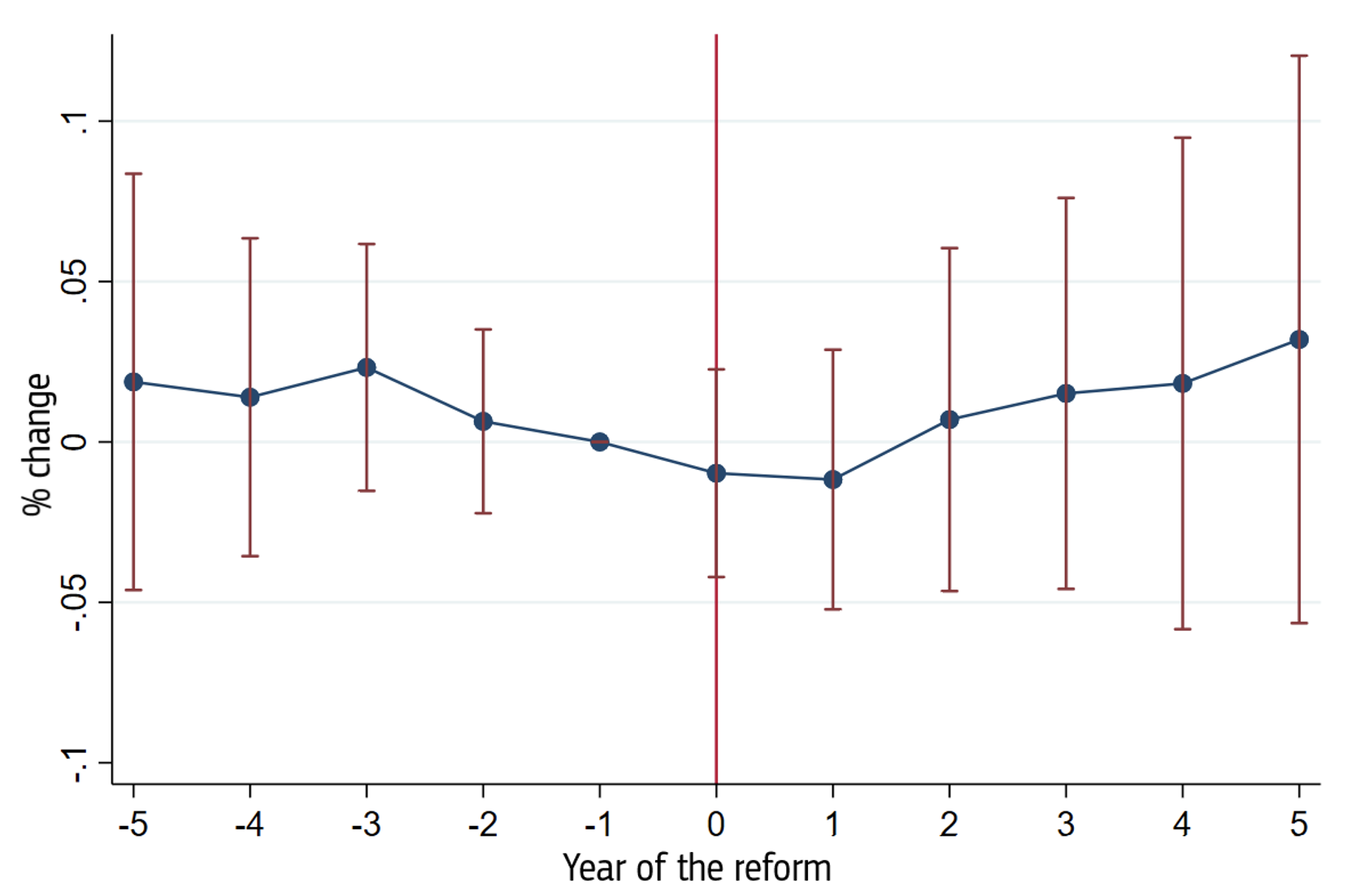

Did this in turn lead to more employment? Figure 2 shows that the effect of the reforms is far from a full ‘work-sharing’ scenario, i.e. a scenario where the fall in average hours worked is entirely offset by a corresponding increase in employment. If anything, after the reform, employment goes down (but the estimates are not statistically different from zero). Moreover, in an affected sector, the total number of hours worked goes down significantly, showing, again, that firms are not substituting lower hours for more workers.

Figure 2 The effect of reductions in working time on employment

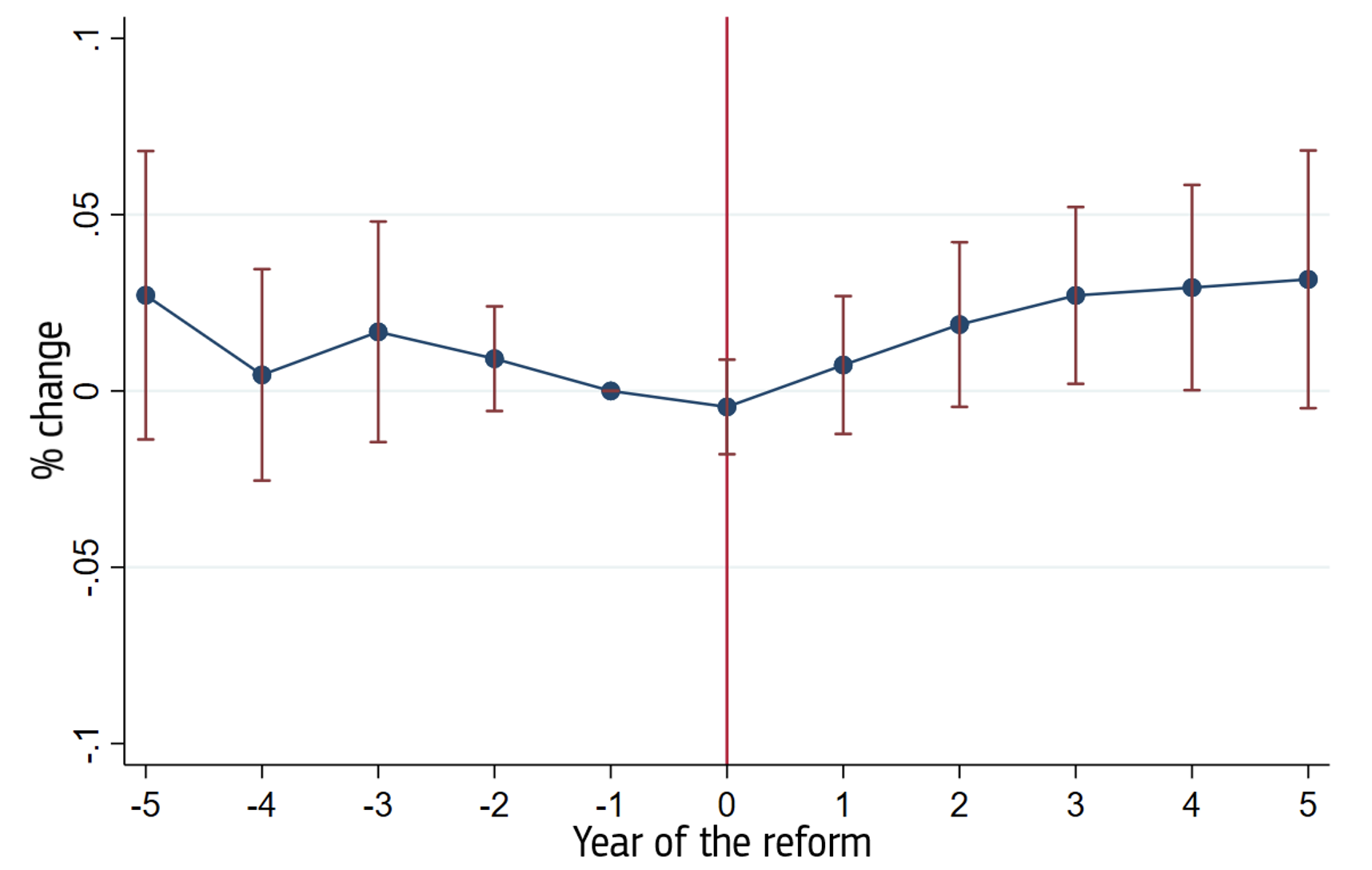

Finally, we look at the effects of reductions in working time on hourly wages and on value added per hour worked (a measure of productivity). In Panel A of Figure 3, the effect on hourly wages of reductions in working time is positive, as one would expect given that reductions in working hours did not entail a decrease in employees’ monthly salary. When looking at value added per hour worked, Panel B appears to show that the reforms led to increased productivity, as many proponents of a reduction in weekly working hours argue. But here again, the estimates for such improvements in productivity are not statistically different from zero (due to low precision, not to the size of the coefficient, which is proportional to the increase in wages/decrease in hours).

Figure 3 The effect of reductions in working time

(A) Effect on hourly wages

(B) Effect on value added per hour worked

Our estimates only make it possible to recover a relative effect (i.e. an effect of the reforms in the difference between sectors more exposed to the reforms and sectors less exposed to the reforms). They do not provide ammunition for those who claim that reducing working hours would lead to a redistribution of work and an increase in total employment.

Nevertheless, if reforms of working time do not hurt workers either in their wages or in employment, and if these reforms also free up more leisure time, it is possible to argue that a shorter working week or day leads to an increase in wellbeing. Lepinteur (2019) shows that workers’ satisfaction increased after the reforms in France and Portugal, while Askenazy (2004) finds an increased work intensification in France. In turn, if there are diminishing marginal returns to longer hours and if workers’ wellbeing increases as a result, a shorter working week or day could also benefit companies through higher productivity and a greater ability to attract and retain workers. The evidence in this respect is, for the time being, very limited. Further work will require more granular data and appropriate identification strategies that the on-going experiments based on voluntary opt-in by companies may not necessarily provide.

Authors’ note: The opinions expressed in this column are those of the authors and cannot be attributed to the OECD or any of its member countries.

References

4 Day Week Global (2022), “US/Ireland pilot program results”.

Askenazy, P (2004), “Shorter work time, hours flexibility, and labor intensification”, Eastern Economic Journal 30(4): 603–14.

Batut, C, A Garnero, and A Tondini (2022), “The employment effects of working time reductions: Sector-level evidence from European reforms”, Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 00: 1–16.

Gomes, P (2021), Friday is the new Saturday, The History Press.

Gross, J (2022), “4-day workweek brings no loss of productivity, companies in experiment say”, New York Times, 22 September.

Kassam, A (2021), “Spain to launch trial of four-day working week”, The Guardian, 15 March.

Lepinteur, A (2019), “The shorter workweek and worker wellbeing: Evidence from Portugal and France”, Labour Economics 58: 204–20.

OECD (2022), “Well-being, productivity and employment: Squaring the working time policy circle”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2022, OECD Publishing.

Poingt, G (2018), “Les 35 heures ont 20 ans: deux économistes font le bilan”, Le Figaro, 9 February.

Portugal News (2022), “Four-day week has a ‘very long way to go’”, 26 October.