A country’s net foreign asset position measures the value of all the assets residents own abroad minus the value of assets foreigners own in the country. It is an important statistic, because all else equal, a higher net foreign asset position means a country can expect higher future net income from abroad, and can thus plan on running larger future trade deficits. One common way to decompose changes in the net foreign asset position is to recognise that the position can improve because a country, on net, acquires additional foreign assets – i.e. it runs a current account surplus – or because the market value of existing assets owned abroad increases relative to the value of foreign-owned assets in the country.

The US has long had a negative net foreign asset position. But until 2007 it was relatively small, never exceeding 20% of US GDP. In fact, the position was surprisingly small given the US history of large and persistent current account deficits. In influential papers, Gourinchas and Rey (2007, 2014) emphasised the importance of valuation effects in shaping the dynamics of the US net foreign asset position. At the time they were writing, these revaluations seemed to move consistently in favour of the US, especially during the mid-2000s. The net effect was that the US appeared to enjoy the special privilege of being consistently able to borrow without running up much debt. Gourinchas and Rey and others argued that this privilege reflected an asymmetry in cross-country portfolios, with Americans owning lots of direct investment and portfolio equity assets abroad – whose value tended to rise over time – while US liabilities consisted disproportionately of low return US government bonds.

Our paper (Atkeson et al. 2022) updates the history of the US net foreign asset position, using data assembled by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis and the US Treasury in the Financial Accounts of the United States. We find that a lot has changed in the last 15 years. First and most notably, the US net foreign asset position has deteriorated very sharply, from negative 5% of US GDP in 2007, to negative 65% of US GDP by the third quarter of 2021. Such a large negative net position is unprecedented. What has driven this decline? What are the welfare implications for Americans?

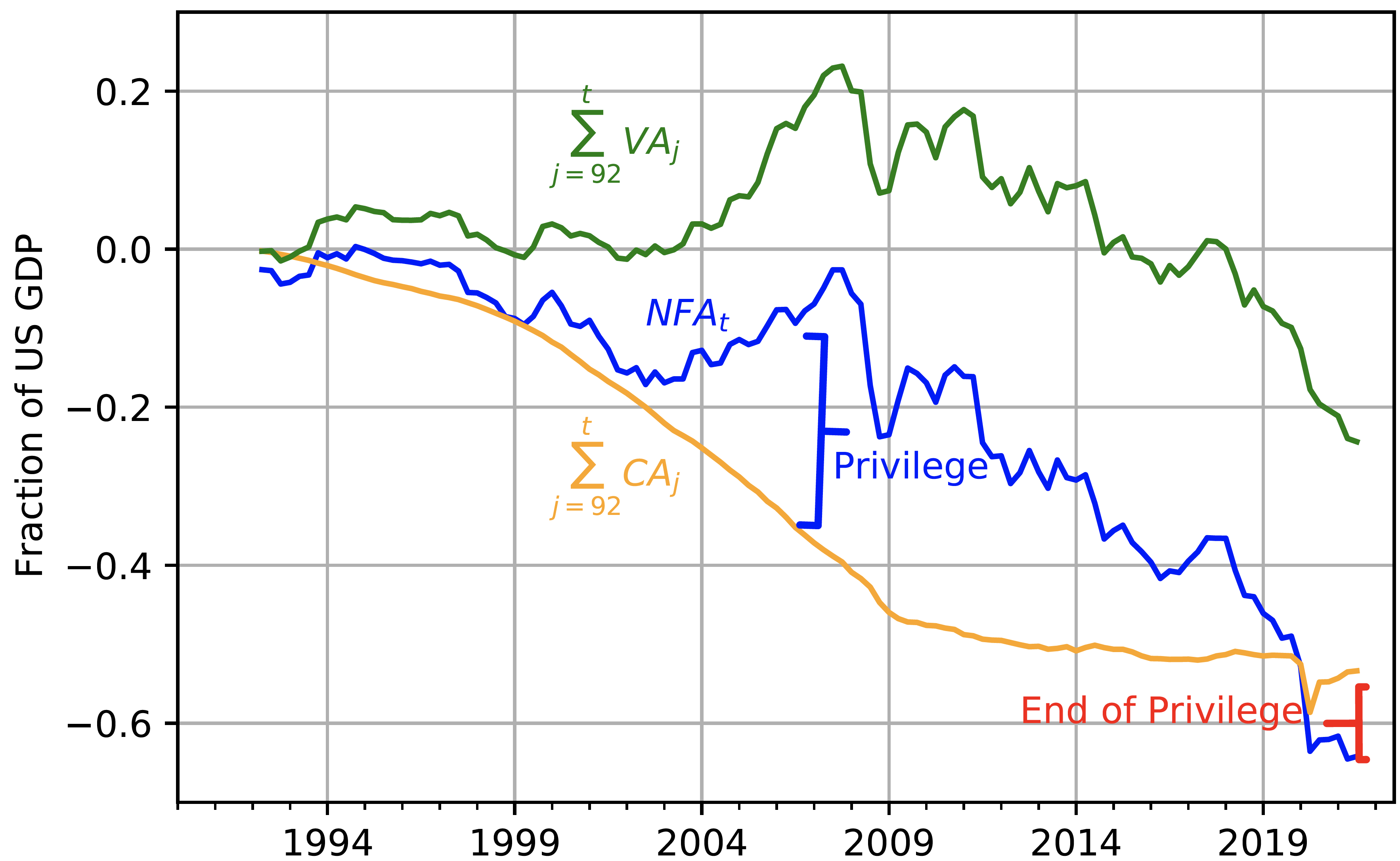

We start by showing that the decline in the US net foreign asset position over this period is mostly driven by valuation effects, with current account deficits playing a minor role. In fact, these valuation effects are so large that the US net position is more negative by the end of 2021 than the sum of all US current account deficits since 1992 (see Figure 1). That is why we title our paper “The End of Privilege.”

Figure 1 The US net foreign asset position (NFA), cumulative current account (CA) deficits, and cumulative valuation effects (VA)

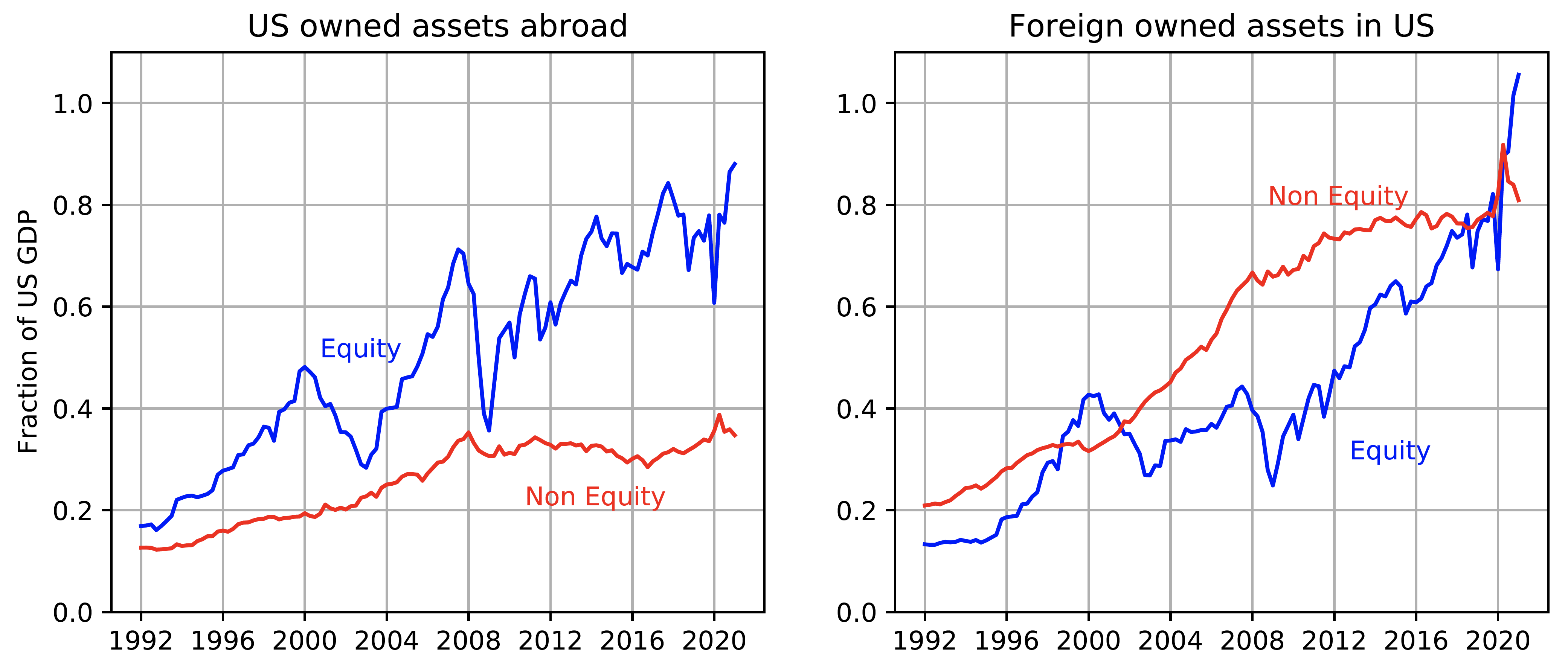

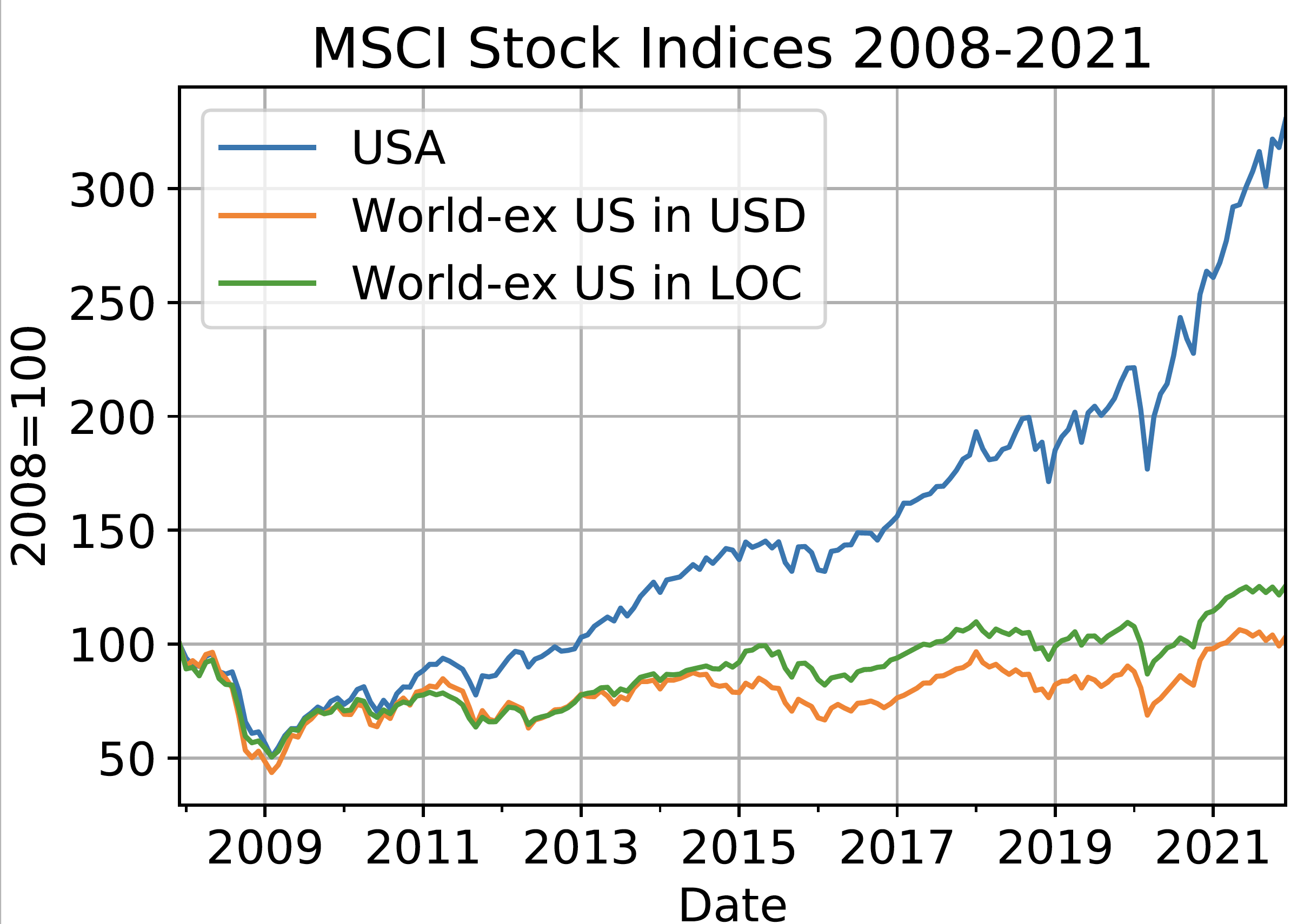

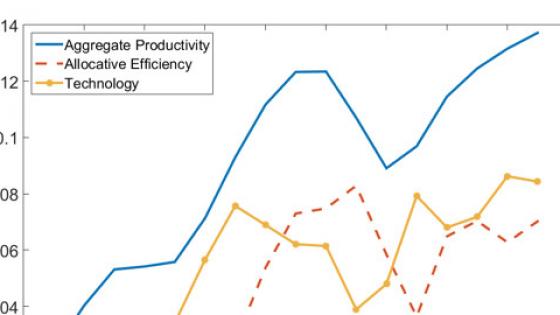

Next, we dig into the source of these valuation effects. We find that valuation effects have driven down the US net foreign asset position because the value of foreign-owned assets in the US has risen rapidly. That might sound surprising to readers under the impression that the US operates like a hedge fund, borrowing from abroad in the form of stable-in-value Treasury bonds, and investing overseas in volatile equity-like investments. But the US financial accounts show that that stylised view of the US international investment position is becoming increasing outdated. In particular, in the post-Great Recession period, foreign-owned equity holdings in the US are large, and similar in value to US-owned equity assets abroad (Figure 2). The US Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that the value of these foreign-owned equity holdings has surged over the past 15 years, in conjunction with the spectacular bull run for the US stock market over this period. At the same time, the value of US-owned assets abroad has risen much more slowly, as foreign equity markets massively under-performed the US (Figure 3). Thus, the market value of US foreign liabilities has risen much more quickly than the market value of US foreign assets, depressing the US net foreign asset position.

Figure 2 US foreign assets and foreign liabilities as a share of GDP

Figure 3 Stock price indexes for the US and for the world excluding the US, in dollars and in local currency

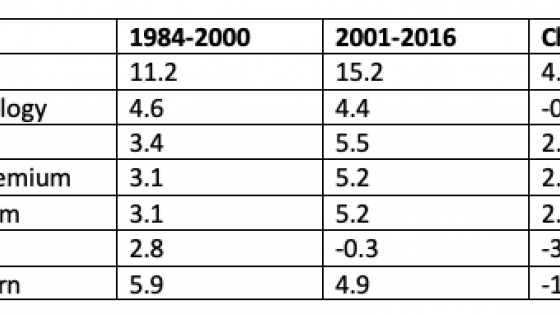

Up to this point, all we have done is simple accounting. Our next objective is to address the welfare implications of the decline in the US net foreign asset position. To do so requires a model within which we can simulate shocks that boost US asset values. Farhi and Gourio (2019) develop a tractable macro asset pricing model that can be used as an accounting framework to trace out the contributions of various possible drivers of asset revaluations. They explore the relative roles in long run macro and asset valuation trends of (1) changes in firm market power, (2) changes in the importance of intangible capital, and (3) changes in risk premia. Greenwald et al. (2022) conduct a similar exercise. They conclude that the most important driver of rising US equity values between 1989 and 2017 was a series of factor share shocks that reallocated output toward shareholders at the expense of workers.

In our paper, we extend a model that is similar to the ones in Farhi and Gourio (2019) and Greenwald et al. (2022) to an international setting, so that we can explore differential cross-country asset valuation dynamics and their implications for the current account and the net foreign asset position. In our model, firms in each country produce differentiated varieties. Each variety can be produced by a more productive ‘leader’ firm, or by a fringe of less productive potential competitors. In equilibrium, leader firms engage in limit pricing, setting markups that are as large as possible while still preserving their production monopoly. We use the model to explore two different possible drivers of a US-specific increase in asset values.

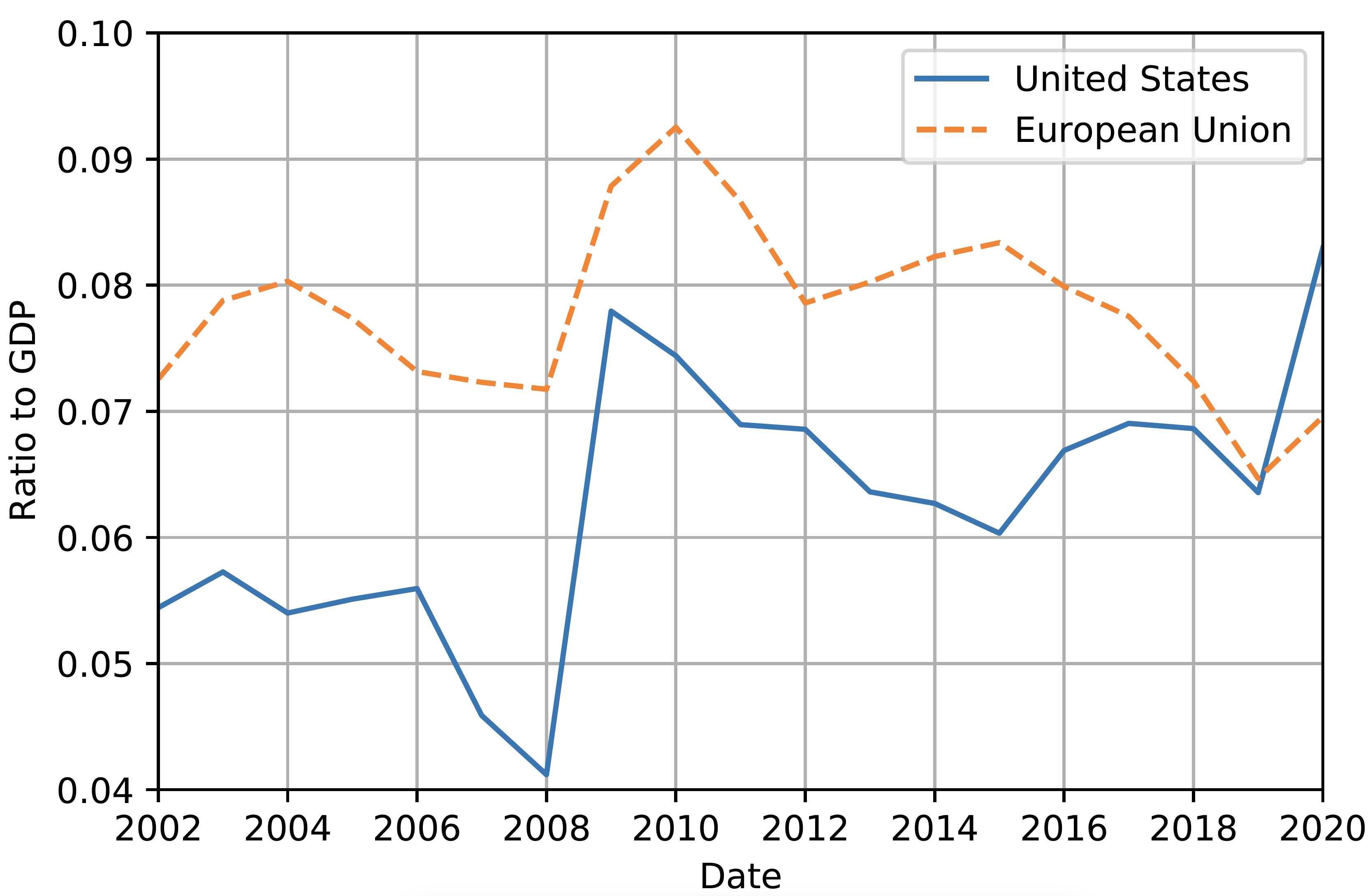

The first hypothesis we entertain is that the productivity differential between leader and follower firms has increased in the US – but not in the rest of the world. This leads to a rise in US markups, in US monopoly profits, and in the value of US firms. From the standpoint of firm owners, the jump in firm values appears as a windfall unexpected excess return to equity. And if these owners are overseas, the shock implies a permanent increase in the share of US income accruing to foreigners. Thus, in this model, the decline in the US net foreign asset position reflects a redistribution of income away from Americans and toward foreigners. We argue that this model of firm values is consistent with two key empirical facts. First, it is consistent with the fact that measured corporate payouts relative to GDP have risen markedly in the US in recent decades, while payouts in other countries have not (see Figure 4). Second, the model is consistent with the fact that US current account deficits have generally been modest in the post-Great Recession period.

Figure 4 Corporate payouts in the US and the EU

We also consider an alternative hypothesis for rising US asset values, which is that production has become more intensive in forms of capital that are poorly measured in national accounts. Under this hypothesis, the value of the US stock market has risen because US (but not foreign) firms have undertaken a lot of investment in unmeasured intangible forms of capital. Along a balanced growth path, it turns out that the higher markups versus more intangible capital models are observationally equivalent. But in our open economy setting, the two models exhibit very different dynamics in the transition from one balanced growth path to another. In particular, if unmeasured capital becomes more important, the model predicts a period of very large (and counterfactual) current account deficits, as the US borrows to invest. Because valuation gains reflect new capital accumulation there are no windfall gains to foreign owners of US firms – whoever finances the unmeasured investment reaps the future returns to that capital.

To conclude, rising international equity diversification has created powerful new channels for shocks to propagate across national borders. Surging US equity values in a context of substantial foreign ownership of US equity have led to a collapse in the US net foreign asset position. Financing this net debt to the rest of the world requires, in expectation, that the US run larger trade surpluses moving forward. Our preferred interpretation of the surge in US equity values is that US firms unexpectedly became more profitable, while foreign firms did not. In a closed economy, this shock would redistribute to American firm owners at the expense of American workers. In our open economy model, the situation for Americans is worse: a large share of the income lost by American workers accrues to foreign owners of US firms. Still, this reallocation might be efficient from an ex ante perspective. A key open question here is whether profits are rising in the US because of the growth of very productive superstar firms in the US (Baqaee and Farhi 2017), or alternatively because US markets are becoming less competitive (Philippon 2020). In the first case, the shock is fundamentally good news for Americans, and transfers abroad might be efficient. The second scenario, in contrast, is a bad news shock for the US, and higher transfers abroad make a bad situation worse.

References

Atkeson, A, J Heathcote and F Perri (2022), “The End of Privilege: A Reexamination of the Net Foreign Asset Position of the United States”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17268.

Baqaee, D and E Farhi (2017), “Aggregate productivity and the rise of mark-ups”, VoxEU.org, 4 December.

Farhi, E and F Gourio (2019), “Accounting for macro-finance trends”, VoxEU.org, 10 March.

Gourinchas, P-O and H Rey (2007), “International Financial Adjustment”, Journal of Political Economy 115(4): 665–703.

Gourinchas, P-O and H Rey (2014), “External Adjustment, Global Imbalances, Valuation Effects”, in Gopinath, G, E Helpman and K Rogoff (eds), Handbook of International Economics, vol. 4, edited by. North Holland, 585–645.

Greenwald, D, M Lettau and S Ludvigson (2021), “How the Wealth was Won: Factor Shares as Market Fundamentals”, NBER Working Paper 25769.

Philippon, T (2020), “The Great Reversal”, VoxEU.org, 12 June.