The world is heading towards elections that will affect half the world’s population – that is, four billion people (Economist 2024). Past studies have shown that elections can raise economic uncertainty, reduce macroeconomic stability, and cause fiscal deteriorations (e.g. Rodden et al. 2020, Fetzer and Yotzov 2023, de Haan and Gootjes 2023). Often termed ‘political budget cycles’, election-induced fiscal deteriorations have been well documented in the literature (Nordhaus 1975, Rogoff and Sibert 1988, Brender and Drazen 2005, Shi and Svensson 2006).

The potential fiscal impact of national elections is particularly relevant to emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), as fiscal positions have turned fragile in many of them and government debt stocks have reached historic highs (Rogoff et al. 2021, Brandao-Marques et al. 2023). With most of the world’s population – and most extreme poor – living in EMDEs, will elections further derail fiscal positions in these countries where sustainability is already at risk? To assess this risk it is important to quantify political budget cycles (PBCs) in these countries and also consider ways to mitigate the impact of elections on fiscal policies.

Do fiscal positions deteriorate around elections in EMDEs?

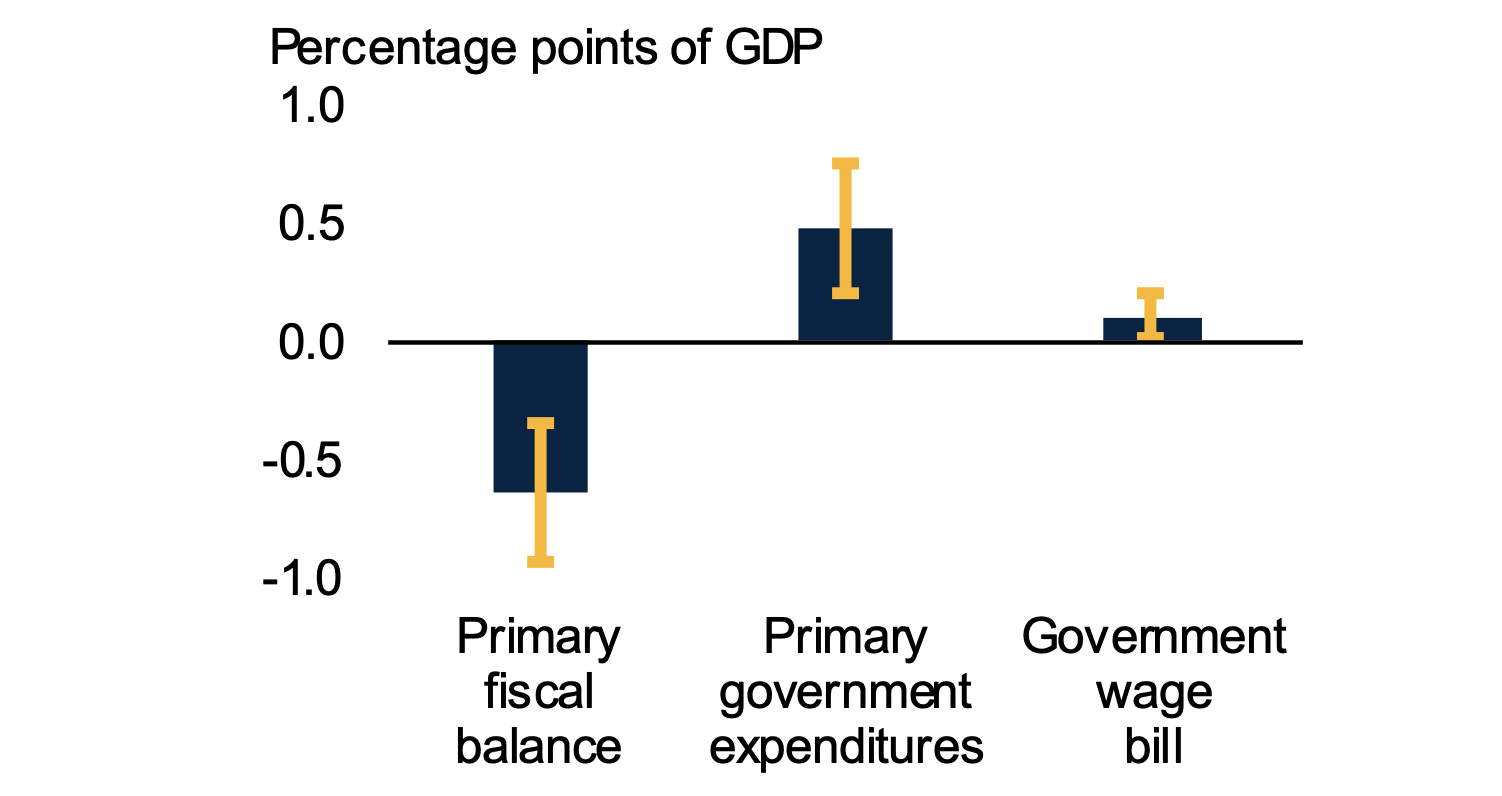

To answer this question, we explore political budget cycles in 104 EMDEs during 1993-2022 in a panel regression of fiscal outcomes on an election variable. We find that primary fiscal deficits, primary government expenditures, and wage bills tended to rise significantly around election years (Figure 1, de Haan et al. 2023). On average, the primary deficit widened by 0.6 percentage points of GDP in an election year, mostly because primary government spending rose by 0.5 percentage points of GDP. Government wage bills were on average 0.1 percentage points of GDP higher in election years.

It turns out that this election-induced fiscal deterioration is by no means unique to democracies. While democratic and non-democratic regimes may differ in some of their fiscal outcomes, they do not significantly differ in election-induced fiscal responses. This is consistent with studies that have argued that non-democracies also have incentives to manipulate fiscal policy during elections (Higashijima 2022, Han 2022).

Figure 1 Change in fiscal indicators in elections

Note: Coefficient estimates from a panel generalised-method-moments (GMM) regression of elections on the primary fiscal balance (in percent of GDP), primary government expenditures (in percent of GDP), and compensation of employees (in percent of GDP), controlling for country characteristics. The sample includes up to 104 EMDEs for 1993–2022. Yellow whiskers indicate 90% confidence intervals.

Source: de Haan et al. (2023).

Are fiscal deteriorations around elections unwound after an election?

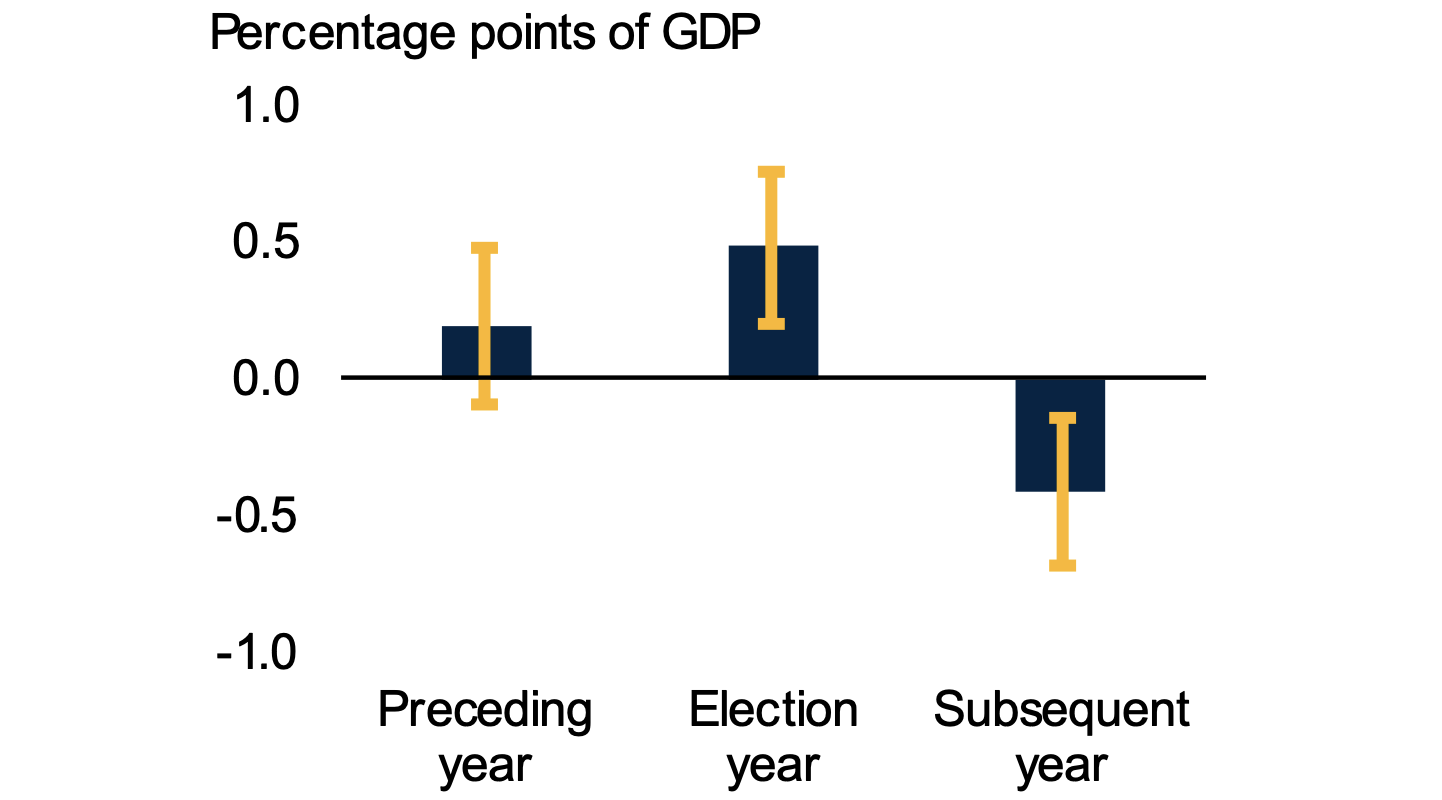

One might expect the election-induced fiscal expansion to be unwound after an election to preserve or restore fiscal sustainability (Ebeke and Ölçer 2017). Indeed, in our sample we do find that primary spending increases in election years were largely reversed in the following year (see Figure 2). However, this was not the case for increases in primary deficits or government wage bills.

Figure 2 Change in primary government expenditures around elections

Note: Coefficient estimates from a panel generalised-method-moments (GMM) regression of elections on the primary fiscal balance (in percent of GDP), primary government expenditures (in percent of GDP), and compensation of employees (in percent of GDP), controlling for country characteristics. The sample includes up to 104 EMDEs for 1993–2022. Yellow whiskers indicate 90% confidence intervals. “Preceding year” is the coefficient on a lead of the election variable, and “Subsequent year” is the coefficient on the lagged election variable.

Source: de Haan et al. (2023).

Policy implications

As increases in the primary fiscal deficit and the government wage bill around elections persist after elections, they can cumulate to sizable increases over the course of several elections. Eventually, this can threaten the sustainability of public finances over time and, in the case of government wage bills, increase spending rigidities.

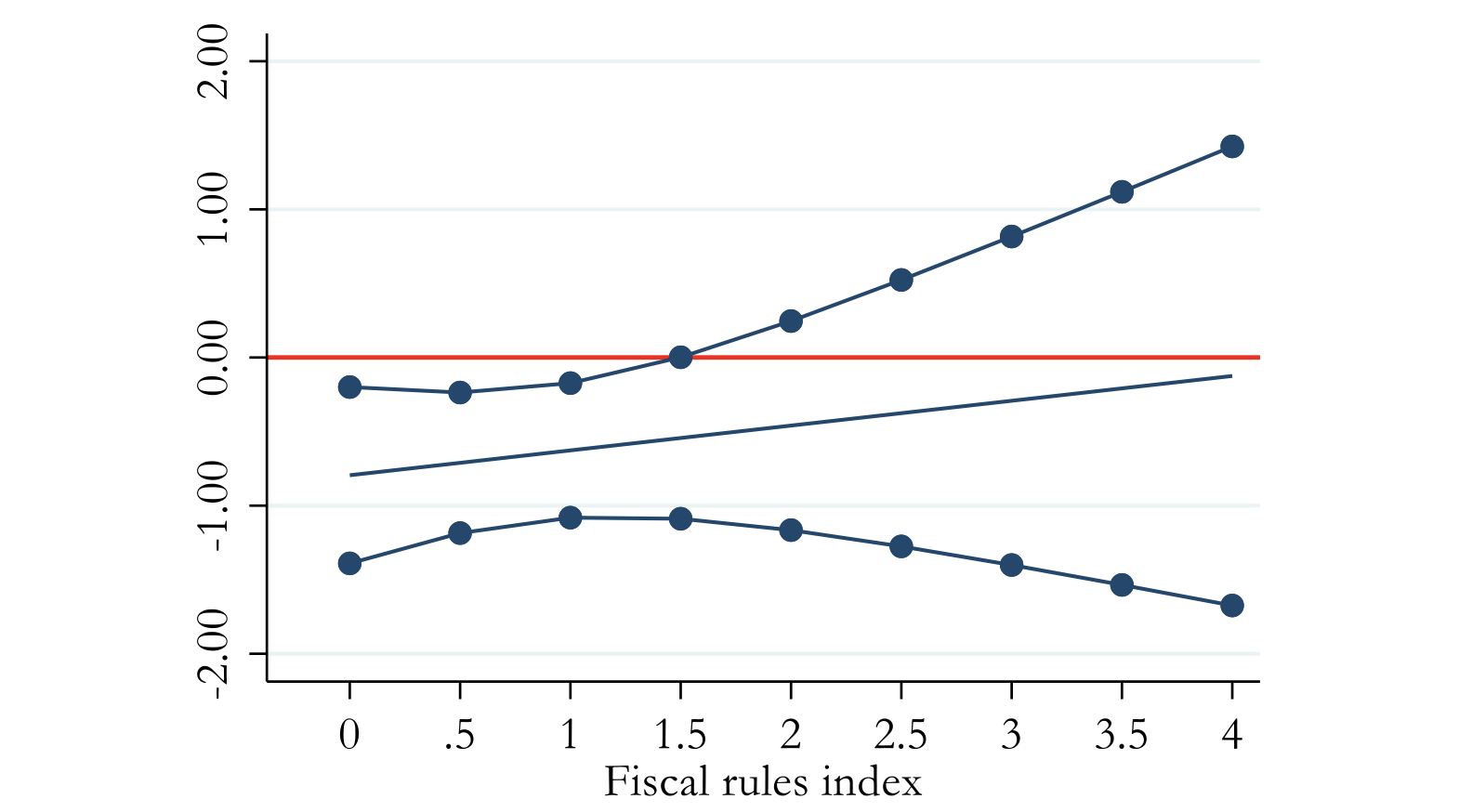

The literature points to some measures that countries can take to constrain fiscal policy choices during elections (Gootjes et al. 2021). We test for three of these measures – the presence of fiscal rules, a better-informed electorate, or an IMF programme – by adding interaction terms with the election indicator in our panel regression. We find that the link between elections and fiscal outcomes weakens or even disappears in the presence of fiscal rules, an IMF programme, or a better-informed electorate (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Marginal effect of elections on primary budget balance outcomes conditional on fiscal rules index

Source: de Haan et al. (2023).

Note: The blue lines show the estimated marginal effects of elections on fiscal outcomes conditioning on fiscal rules index with the dotted blue lines showing the 90% confidence levels. The red line indicates when the marginal effect equals 0.

Authors’ notes: The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this column are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent.

References

Brandao-Marques, L, M Casiraghi, O Harrison and G Kamber (2023), “High Debt Levels Can Hinder the Fight Against Inflation,” VoxEU.org, 28 Jul.

Brender, A and A Drazen (2005), “Political Budget Cycles in New versus Established Democracies,” Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 1271-1295.

de Haan, J and B Gootjes (2023), “Conditional National Political Budget Cycles”, forthcoming in C Bjørnskov and R M Jong-A-Pin (eds), Elgar Encyclopedia of Public Choice, Edward Elgar.

de Haan, J, F Ohnsorge and S Yu (2023), “Election-induced Fiscal Policy Cycles in Emerging Market and Developing Economies,” CEPR Discussion Paper DP18708.

Ebeke C and D Ölçer (2017), “Fiscal Policy over the Election Cycle in Low-Income Countries,” in V Gaspar, S Gupta and C Mulas-Granados (eds.), Fiscal Politics, Washington DC: International Monetary Fund.

Economist (2024) “Elections around the World in 2024,” 12 January.

Fetzer, T and I Yotzov. (2023), “Electoral Surprises and Business Cycles,” VoxEU.org, 10 Aug.

Gootjes B, J de Haan and R M Jong-A-Pin (2021), “Do Fiscal Rules Constrain Political Budget Cycles?” Public Choice 188: 1–30.

Han, K (2022), “Political Budgetary Cycles in Autocratic Redistribution,” Comparative Political Studies 55(5): 727–756.

Higashijima, M (2022), The Dictator’s Dilemma at the Ballot Box: Electoral manipulation, economic maneuvering, and policy order in autocracy, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Nordhaus W (1975), “The Political Business Cycle,” The Review of Economic Studies 42(2): 169–90.

Rodden, J, S Davis, A Baksy, N Bloom and S Baker (2020), “Polarised Elections Raise Economic Uncertainty,” VoxEU.org, 22 Dec.

Rogoff, K and A Sibert (1988), “Elections and Macroeconomic Policy Cycles,” The Review of Economic Studies 55: 1–16.

Rogoff, K, F Ohnsorge, C Reinhart and M A Kose (2021), “Developing Economy Debt after the Pandemic,” VoxEU.org, 3 Nov.

Shi, M and J Svensson (2006), “Political Budget Cycles: Do They Differ across Countries and Why?” Journal of Public Economies 90(8-9): 1367-1389.