After the Global Crisis, traditional monetary policy lost its effectiveness in many countries as nominal interest rates approached zero, and fiscal policy took centre stage. Many countries initially responded to the crisis with fiscal stimuli, but several have since implemented austerity measures. This provoked empirical research on the effects of fiscal policy, particularly on the size of fiscal multipliers (see Ramey 2016 for a recent survey).

At the same time, most advanced economies experienced deep recessions and costly bailouts, and therefore a sharp increase in public debt. This was accompanied, especially in the Euro periphery, by a re-evaluation of sovereign default risk and, because the increase in public debt was absorbed predominantly by domestic banks, a decline in the share of public debt held by foreigners.

Since then, researchers have tried to understand the determinants and macroeconomic consequences of the distribution of public debt between domestic and foreign debtholders (e.g. Arsanalp and Tsuda 2012, Broner et al. 2014, Brutti and Saurè 2016). This debate has resurfaced over the last few months for Italy, which has rising spreads and an increasing share of the country’s public debt held by local residents and financial institutions.

In a recent paper (Broner et al. 2018), we argue that there is a natural connection between fiscal multipliers and the foreign holdings of public debt. The intuition is simple. There are several channels through which fiscal expansions – either increases in public spending or reductions in taxes – can raise domestic economic activity. But fiscal expansions can also crowd out the domestic private sector, since the resources used to acquire public debt can detract from domestic consumption and investment. The effect is likely to be stronger when fiscal expansions are financed by selling public debt to domestic residents rather than foreigners.

As a result, we should expect fiscal multipliers to be larger when governments have access to international debt markets. Our paper provides strong evidence that this is the case. (You can find complementary evidence on this relation using different data and methodology in Priftis and Zimic 2017.)

Foreign holdings of public debt

We illustrated this intuition through a simple model, and we tested it empirically on macroeconomic and public debt data from 17 OECD countries. We used the share of public debt held by foreigners as a proxy for access to international debt markets. For the US, we obtained data on public debt holdings directly from FRED. For the other countries, we constructed a novel annual dataset of the allocation of public debt between domestic and foreign holders. These data were assembled from a variety of sources, including the balance of payments (financial accounts, international investment positions), monetary surveys, and data provided directly by countries’ central banks, ministries of finance, and statistical offices.

Our data reveal interesting patterns:

- There is significant variation across countries. In Canada and Japan for example, the share of public debt held by foreigners is consistently low, whereas in others, such as Finland and Austria, foreigners are holding more than 75% of public debt towards the end of the sample period.

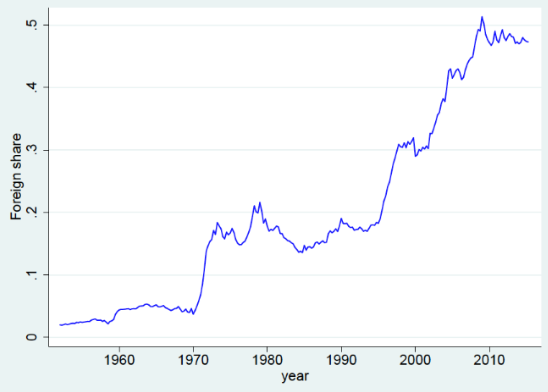

- An increasing share of public debt is in the hands of foreigners. This general pattern is in line with the rise of financial globalisation. In the US, for instance, the share of public debt held by foreigners has increased from less than 5% in the 1950s to close to 50% today (Figure 1).

- The increase has not been systematic over time. Although this general increase has been observed across most OECD economies, during the recent European debt crisis, for instance, there was a decline in the share of debt held by foreigners in the euro periphery.

Figure 1 Foreign share of US public debt holdings

Notes: Foreign share is the rest of the world’s holdings of US federal government’s treasury securities liabilities as a proportion of total US federal government treasury securities liabilities.

Source: Broner et al. (2018).

Estimating multipliers

In our empirical analysis we follow existing methodologies, both regarding the identification of fiscal shocks and the empirical specifications used to estimate the size of fiscal multipliers.

Regarding fiscal shocks, we use two alternative approaches:

- Ramey and Zubairy (2018) data on shocks to government spending in the US, and Guajardo et al. (2014) data on fiscal consolidations in a group of OECD economies, both of which are based on the narrative approach.

- For the US, we also estimate shocks to government spending by using the structural VAR approach of Blanchard and Perotti (2002).

We follow the Ramey and Zubairy (2018) empirical method to estimate the size of multipliers:

- We use the fiscal shocks described above to instrument the fiscal variable of interest, government spending or public deficit shocks.

- We then use this instrumented fiscal variable to estimate the corresponding multiplier.

In both steps we use the local projection method from Jordà (2005).

We use these methodologies to estimate baseline, unconditional multipliers. We then incorporate the share of public debt held by foreigners to estimate conditional multipliers.

Our main result is that the fiscal multipliers are increasing in the share of public debt held by foreigners. This result holds both for the post-war US economy, and for a panel of OECD economies over the last few decades. According to our estimates, the public spending multiplier in the US was significantly smaller than in the 1950s, when the foreign share was less than 5%, and significantly greater than in 2014, when the foreign share was close to 50%. In addition, the estimated deficit multiplier in our sample of OECD economies is also smaller than it is for low levels of foreign share, such as Japan's 8%, and larger than for high levels of foreign share, such as Ireland's 64%.

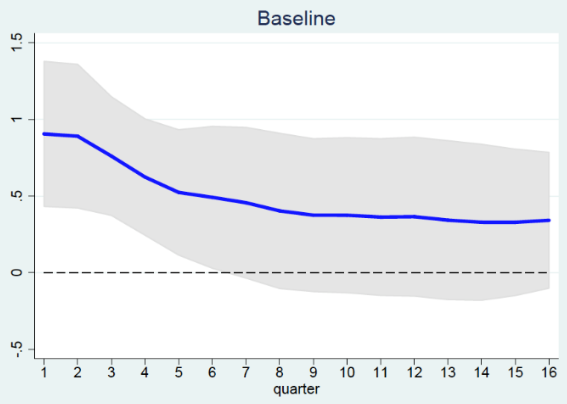

Using the US as an illustration, Figure 2 plots the unconditional cumulative multipliers for up to a four-year horizon. The estimated multiplier is 0.9 for the first quarter before declining to 0.4 after two years. It is statistically significant at the 1% level for the first four quarters.

Figure 2 Baseline model, US output multiplier

Notes: Cumulative GDP multiplier from a defence news shock equal to 1% of GDP. The shaded area represents the 90% confidence bands.

Source: Broner et al. (2018).

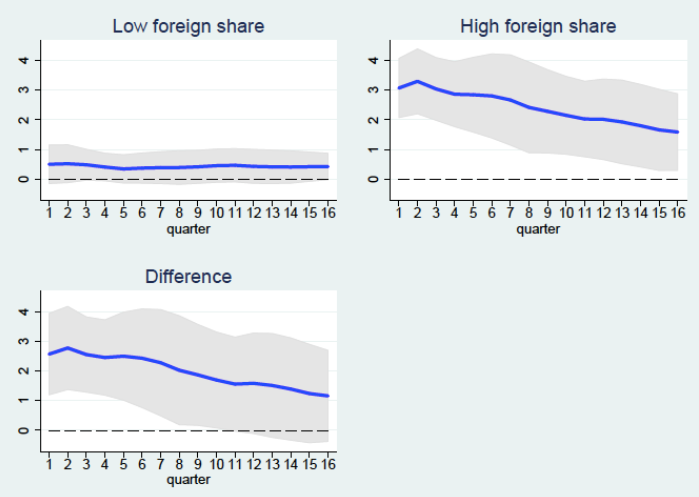

Figure 3 plots instead the cumulative multiplier for up to a four-year horizon conditional on the foreign share of public debt. The first panel in the figure plots the cumulative multipliers for a low foreign share of 3%, which corresponds to the 10th percentile of foreign holdings in the sample. These cumulative multipliers are statistically indistinguishable from zero, and likely smaller than one at all horizons. The second panel plots the cumulative multiplier for a high foreign share of 47%, which corresponds to the 90th percentile of foreign holdings in the sample. These cumulative multipliers are statistically different from zero at all horizons and significantly greater than one for up to two years. The third panel plots the difference between the cumulative multipliers for high and low foreign share.

Figure 3 Foreign share, US output multiplier

Notes: Cumulative GDP multipliers from a defence news shock equal to 1% of GDP with low (10thpercentile of foreign holdings in the sample) and high (90thpercentile) foreign share, and the difference between the two multipliers. The shaded area represents the 90% confidence bands.

Source: Broner et al. (2018).

Implications

These findings challenge the conventional wisdom on fiscal multipliers in open economies. The traditional Mundell-Fleming model implies that multipliers are smaller in open economies because part of the effect of fiscal expansions on aggregate demand falls on foreign goods.

Our findings instead point to an alternative interpretation of the inflow of foreign goods. That is, they reflect capital inflows that help finance fiscal expansions, minimising their crowding-out effects on domestic investment.

In a similar vein, the common perception is that fiscal expansions have positive spillovers on other countries because they raise demand for foreign goods. Our findings instead point to a potentially negative spillover. To the extent that fiscal expansions are financed by foreigners, their associated crowding-out effects are felt abroad and consumption and investment fall elsewhere. More broadly, our results suggest that the effects of fiscal expansions in a globalised world depend crucially on how they are financed.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Spain, the ECB or the European Stability Mechanism.

References

Arslanalp, S and T Tsuda (2012), “Tracking Global Demand for Advanced Economy Sovereign Debt”, IMF working paper 12/284.

Blanchard, O and R Perotti (2002), “An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4): 1329-68.

Broner, F, D Clancy, A Erce, and A Martin (2018), “Fiscal Multipliers and Foreign Holdings of Public Debt”, European Stability Mechanism working paper 30.

Broner, F, A Erce, A Martin, and J Ventura (2014), “Sovereign Debt Markets in Turbulent Times: Creditor Discrimination and Crowding-Out Effects”, Journal of Monetary Economics 61: 114-142.

Brutti F and P Sauré (2016), "Repatriation of debt in the euro crisis", Journal of the European Economic Association 14(1): 145-174.

Guajardo, J, D Leigh, and A Pescatori (2014), “Expansionary austerity? International evidence”, Journal of the European Economic Association 12(4): 949-968.

Jordà, O (2005), “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections”, American Economic Review 95(1): 161-182.

Priftis, R and S Zimic (2017), "Sources of borrowing and fiscal multipliers", EUI working paper 2017/01.

Ramey, V A (2016), “Macroeconomic shocks and their propagation”, Chapter 2 in J B Taylor, H Uhlig (eds.), Handbook of Macroeconomics, Volume 2, Elsevier.

Ramey, V A and S Zubairy (2018), "Government spending multipliers in good times and in bad: Evidence from US historical data", Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.