Online betting on sports has grown substantially in the last decade and is projected to become a huge market in the US after the Supreme Court abolished federal restrictions on sports betting in 2018. Over 30 US states have now legalised sports betting and huge sums are being spent on marketing by new bookmaking firms to attract new clients. This raises the question of what happens to the money being gambled.

Research has shown that pari-mutuel betting on horses – where the money placed is pooled and paid back to those who picked the winners minus a fraction that goes to the operator – features a ‘favourite-longshot’ bias (Snowberg and Wolfers 2008). Money placed on the favourites loses less than money placed on longshots. Explanations for this pattern include people being unable to judge small probabilities correctly (Thaler and Ziemba 1988) and some bettors enjoying taking riskier bets (Quandt 1986).

Modern online sports betting does not use the pari-mutuel structure. Instead, it features fixed odds set by bookmakers, who make offers like “You take back €3 if your pick wins and lose your €1 bet otherwise”. If a bettor accepts this offer, their odds are not changed by subsequent actions of other bettors. Some studies have found favourite-longshot bias in fixed-odds markets (Berkowitz et al. 2017) while others have not (Paul and Weinbach 2005).

In a recent paper (Hegarty and Whelan 2023a), we compare two different fixed odds markets for betting on European soccer. For the same set of matches, we find one market shows a strong pattern of favourite-longshot bias while the other does not. Here, we summarise our evidence and discuss its implications for understanding the key factors underlying favourite-longshot bias.

Betting on a home win, away win, or draw

The traditional way to bet on soccer is to back one of the three possible outcomes. This is how the ‘high street’ European bookmakers take most of their bets on soccer. These bookmakers are known to engage in various restrictive practices, limiting how much can be placed and banning serial winners.

Under the null hypothesis that all bets are priced with the same profit margin, it is easy to extract the implied odds and the bookmaker’s margin from these markets. For example, suppose you are betting on Chelsea versus Arsenal and the amounts you will get back with a winning €1 bet will be €1.90 if you bet on Arsenal to win, €4.76 if you bet on the draw, and €3.17 if you bet on Chelsea to win. If bookmakers are not expected to make profits on average, you can calculate the probabilities of the outcomes as the inverse of these odds. In this case, Arsenal would have a 52.5% probability of winning, Chelsea a 31.5% probability of winning, and there would be a 21% chance of a draw. But these probabilities sum to 105%; this is due to the bookmaker’s profit margin. If the margin has been applied equally across all bets, we can ‘normalise’ the probabilities to get the true probabilities as 50% for an Arsenal win, 20% for a draw, and 30% for a Chelsea win.

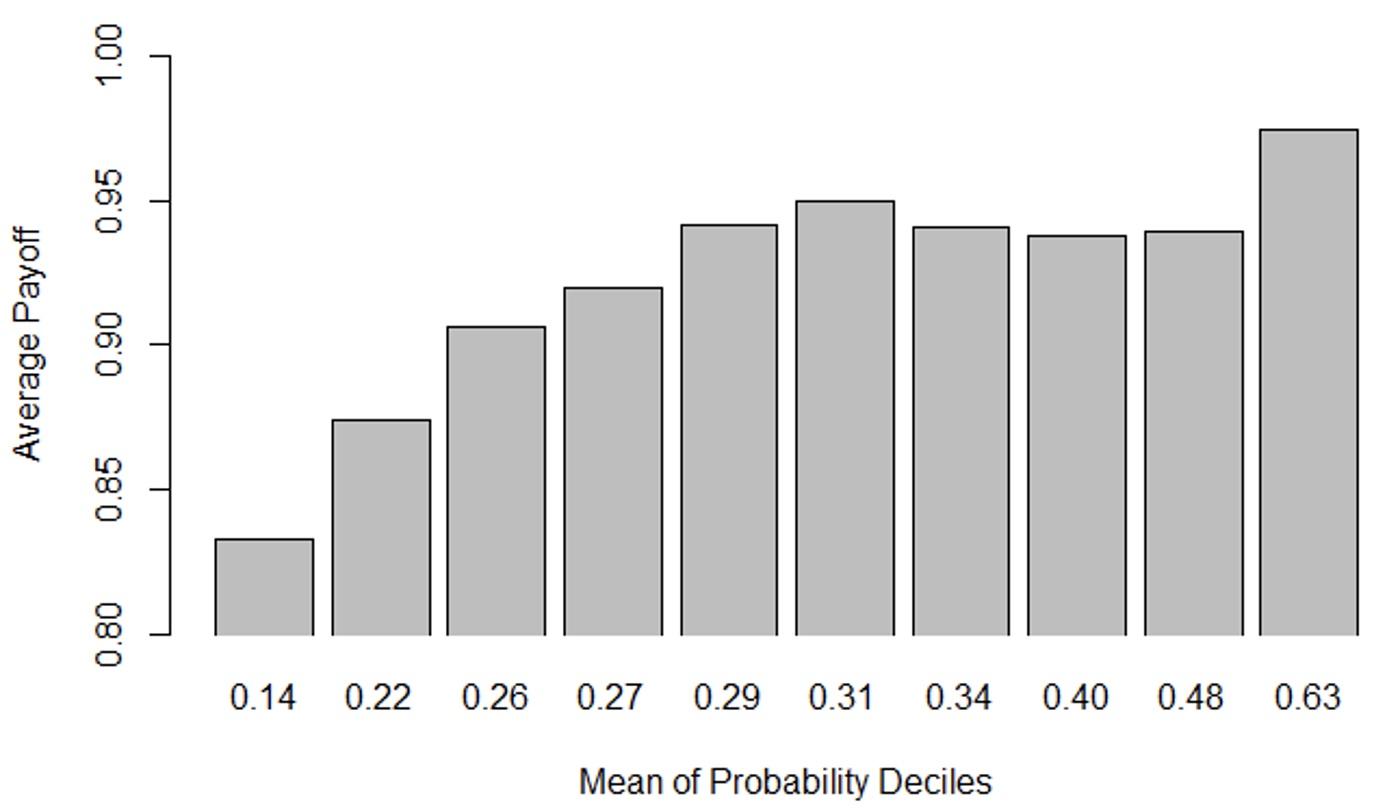

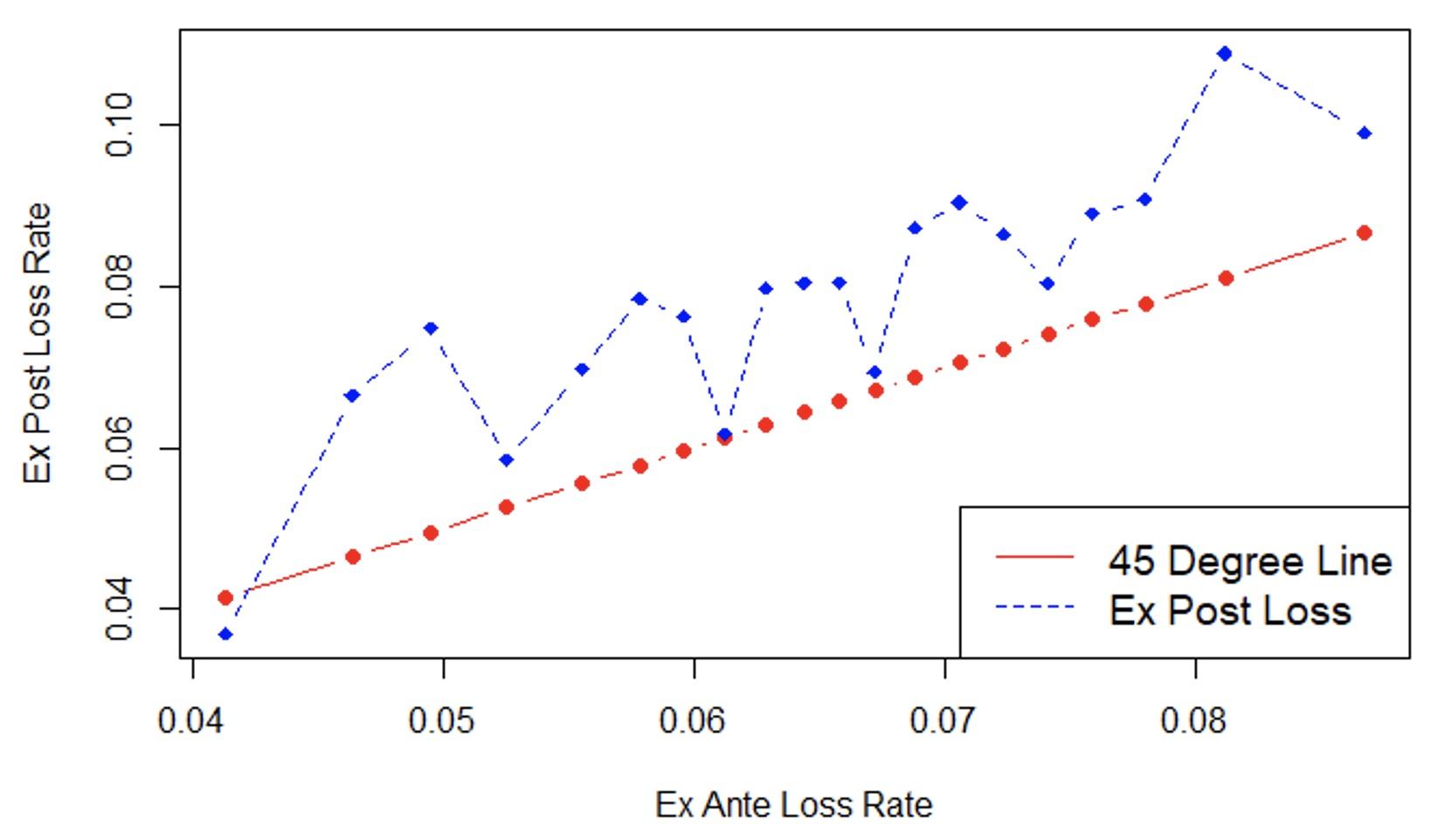

We use this method to estimate the probability of winning for 252,690 bets placed on 84,230 European soccer matches played between 2011 and 2022. We then sort the data into deciles of this estimated probability and then calculate the average payoff on a €1 bet for each set of bets. Figure 1 shows a pronounced pattern of favourite-longshot bias, supporting previous evidence for European soccer with a smaller dataset presented by Angelini and De Angelis (2019). We also document another market inefficiency. The average loss rates across all bets are higher than suggested by the usual calculation of the bookmaker’s margin, based on the sum of the inverses of the odds. In Hegarty and Whelan (2023b), we show that when bookmakers set higher margins for bets with a low probability of winning, then the usual measure of the expected loss on bets is systematically biased downwards.

Figure 1 Average payouts for the probability deciles of home/away/draw bets

Figure 2 Average loss rate on home/away/draw bets, sorted by expected loss rate

Asian handicap betting

We also looked at the odds on the same matches in a large online betting market that has emerged in recent years – the ‘Asian handicap’ market. Payouts on Asian handicap bets depend on an adjustment of the match result that applies a deduction (known as a handicap) to the goals total of the team considered more likely to win. For example, if Arsenal play Chelsea at home and the Asian handicap is quoted at -2 (meaning a two goal deduction is applied to Arsenal's total), then a bet on Chelsea would pay out even if they lost the game by one goal. If the result precisely matches the handicap (in the above example, Arsenal beat Chelsea by two goals) then all bets are refunded. Unlike in US spread betting, the handicaps do not usually equalise the chances of the two sides of the bet winning, so differing payout odds are generally offered for the bets on the two teams.

From being almost unheard of outside Asia in the 1990s, the Asian handicap betting market for soccer has become increasingly important around the world over the past 20 years. While information on its betting volumes is not publicly available, it seems likely the Asian handicap market now accounts for a high share of betting on European soccer matches. Much of the volume is placed with so-called ‘sharp’ bookmakers such as Pinnacle, which have low profit margins per bet and offset this with high betting volumes. These bookmakers do not impose restrictions on how much can be placed and do not ban serial winners, instead using their bets to improve odds. Indeed, selling probabilities to retail bookmakers is one of their business lines. This market's low margins make it particularly attractive for well-informed bettors and professional betting syndicates. This raises the question of whether the odds in this market have different properties to more traditional markets.

Asian handicaps are set in quarter-goal increments: a bet with a handicap of 1.25 places half the money on a bet with a handicap of 1 (where a refund is possible) and half of it on a handicap of 1.5 (where there are no refunds). With betting amounts equally spread across the various handicaps, this means three-quarters of Asian handicap bets feature a refund. With two odds on offer and three possible outcomes (Chelsea bet wins, Arsenal bet wins, and refund), the mapping from odds to probabilities is more complex for this market. We develop a new methodology – based on the estimated probability of a refund for each kind of bet – to estimate the probability of a win for each bet and also the expected loss rate. We show that these probabilities are unbiased predictors of the actual outcomes.

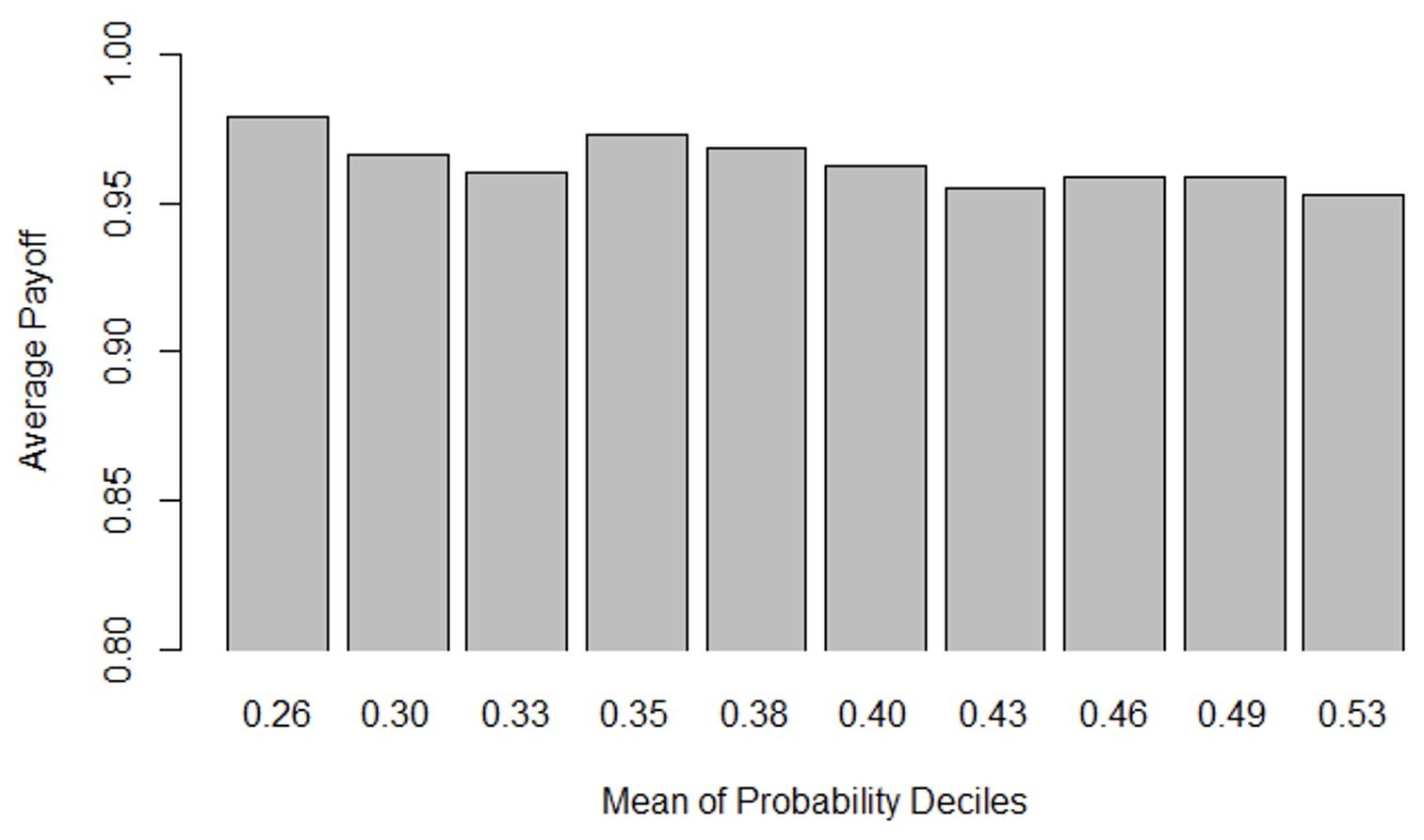

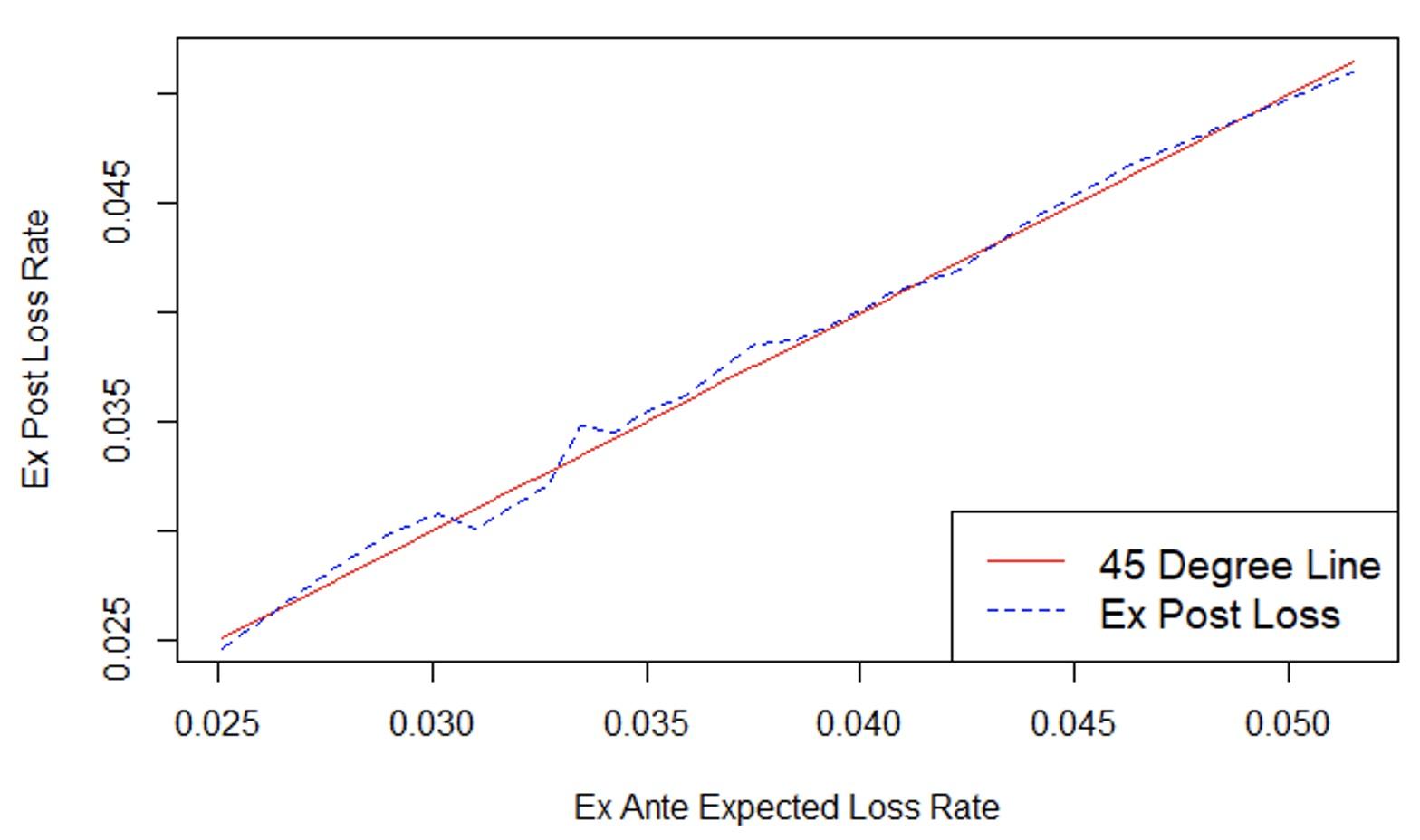

Figure 3 shows average payoffs for Asian handicap bets across probability deciles for the same set of 84,230 matches. Unlike betting on home win, away win or draw, bets in this market do not show any favourite-longshot bias. (The handicap market has a narrower range of probabilities, but home /away/draw bets in this probability range still feature a significant favourite-longshot bias). Figure 4 shows that ex-post loss rates on bets are lower than for the home/away/draw market and are in line with the expected ex-ante losses predicted by our method.

Figure 3 Average payouts by probability deciles for Asian handicap bets

Figure 4 Average loss rates on home/away/draw bets, sorted by expected loss rate

Possible explanations

What explains these results? One explanation is a difference in customer base. The low-margin ‘winners welcome’ ethos of the sharp bookmakers that dominate the Asian handicap market attracts syndicates and professional bettors. These bookmakers, however, do not have a retail presence in Europe and opening accounts with them is tricky in many European countries. This leaves those who bet smaller stakes and are perhaps less informed to place their bets with ‘traditional’ bookmakers. There is also perhaps a difference in attitudes to risk across the customer base of the two markets, with bettors making smaller bets in the home/away/draw market perhaps having greater preference for risky longshot bets than those who have large amounts of money at stake in the Asian handicap market.

One explanation that does not fit our evidence is the idea, due to Shin (1993), that favourite-longshot bias is a response by bookmakers to the possibility of inside information. In our case, the Asian handicap market is more likely to have highly informed insiders and yet it does not feature biased odds.

Beyond the differences in customer bases, another explanation is the competitive structure of the two markets. The low margins in the Asian handicap market suggest a high level of competition. In contrast, we have shown that bookmakers in the home/away/draw market are making big profits on bets on longshots, which suggests a lack of competition because these high profits are not being competed away by some bookmakers choosing to offer more attractive odds. The roles played by differences in customer base and competitive structures are likely to be useful areas for future research.

References

Angelini, G and L De Angelis (2019), “Efficiency of Online Football Betting Markets”, International Journal of Forecasting 35(2): 712–721.

Berkowitz, J, C Depken and J Gandar (2017), “A Favorite-Longshot Bias in Fixed-Odds Betting Markets: Evidence from College Basketball and College Football”, Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 63: 233-239.

Hegarty, T and K Whelan (2023a), “Forecasting Soccer Matches With Betting Odds: A Tale of Two Markets”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17949.

Hegarty, T and K Whelan (2023b), “Calculating The Bookmaker's Margin: Why Bets Lose More On Average Than You Are Warned”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17948.

Paul, R and A Weinbach (2005), “Market Efficiency and NCAA College Basketball Gambling,” Journal of Economics and Finance 29: 403-408.

Quandt, R (1986), “Betting and Equilibrium”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 101: 201-208.

Shin, H S (1993), “Measuring the Incidence of Insider Trading in a Market for State-Contingent Claims”, Economic Journal 103: 1141-1153.

Thaler, R and W Ziemba (1988), “Anomalies: Parimutuel Betting Markets: Racetracks and Lotteries'', Journal of Economic Perspectives 2: 161-174.