Over the past century, there has been a remarkable increase in women’s participation in the labour market, accompanied by gradual gender convergence in earnings (Goldin 2006). Despite the progress, sizeable gaps remain in most labour market outcomes, largely driven by the unequal distribution of men and women across industries and occupations (Goldin 2014, Blau and Kahn 2017, Petrongolo and Ronchi 2020).

Academia is one of the occupations where women remain under-represented (Iaria et al. 2022), which is a matter of growing concern for researchers and policymakers. This includes the field of economics, where extensive research on gender dynamics – ranging from the publication process to the general climate in the profession (e.g. Card et al. 2020, Hengel 2022, Ductor et al. 2023, Wu 2020, Dupas et al. 2021) – has flourished recently, leading to policy initiatives aimed at addressing disparities in the field, such as the AEA Initiatives for Diversity and Inclusion.

A crucial aspect in understanding current gender gap dynamics and anticipate future trends among scholars in economics is to analyse their evolution from past decades to present times. Are these gaps still narrowing for each new generation that enters the profession, or have they stabilised?

We answer this question in a recent paper (Ayarza and Iriberri 2024), in which we study the evolution of gender gaps in representation and research output among cohorts of scholars in economics over the past nine decades (1933 to 2019). A particular advantage of studying scholars in economics is that the most relevant performance variable which relates to salaries, promotion, and status in the profession – publications over individual scholars’ careers – is quantifiable, observable and comparable over time.

We use the dataset created by Card et al. (2022), which includes any active researcher publishing at least once in any of the 36 high-impact journals in the field of economics, his or her publication record in these journals, and accumulated citations of publications in the so-called ‘top five’ journals.

We define cohorts of scholars as those authors who share the same year of their first publication, and we count their publications and citations over a career of at most 24 years. To gain insight into the vertical and horizontal segregation in representation and its effects on research output, we categorise authors by prominence (overall versus top five scholars, defined as those who have at least one top five publication) and by field of study (scholars in ‘feminine’ fields, defined as those who publish in top field journals in public economics, health economics, labour economics or development; and scholars in ‘masculine fields, i.e. those who publish in top field journals in microeconomics, macroeconomics, finance or econometrics) and analyse the results for the different samples across cohorts over time.

Female representation across cohorts

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the female share for all active scholars, ‘top five’ scholars and scholars working in ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ fields in economics.

For all active scholars, the solid black line shows a continuous improvement in female representation across cohorts, notably since the 1980s: 10% of scholars who began their publishing career in the 1980s were women, compared to 25% in 2019.

The lower representation of women among ‘top five’ scholars (dashed black line) compared to all scholars (solid black line) across cohorts indicates persistent vertical segregation in economics, mirroring trends in other sectors. This gap has, if anything, widened since 2005, now standing at 5 percentage points.

Horizontal segregation has intensified over time too. In the 1980s cohorts, ‘feminine’ fields had a 7 percentage point higher share of female scholars compared to ‘masculine’ fields, whereas by the 2019 cohort, this gap had widened to 15 percentage points (illustrated by the difference between the solid red/blue lines in Figure 1).

Figure 1 Share of female scholars by cohort

Notes: The figure shows the share of female scholars by cohort for different samples according to authors’ prominence: 1) all active scholars (solid lines) and 2) ‘top five’ scholars (dashed lines) i.e, those who have published at least once in any of the top five economics journals, and according to field: (1) scholars in feminine fields (in red) i.e. scholars who have a strictly higher number of publications in the 4 top-field journals with consistently highest share of female authors among the eight top field journals (JPubE, JDE, JHE, JOLE); and (2) scholars in ‘masculine’ fields (in blue) i.e., scholars who have a strictly higher number of publications in the remaining four top field journals (JF, JET, JE, JME).

Gender gaps in publications across cohorts (1933-1996)

We next turn to the most important output for scholars: number of publications.

Figure 2a shows that, on average, female scholars in the overall sample published between 2.6 fewer publications (cohorts in the 1933-1939 decade) and 1.2 fewer publications (cohorts in the 1990-96 decade) than male scholars over their academic career of at most 24 years. The figure shows that the gaps are even more negative among ‘top five’ scholars. More concerning, although we observe some convergence in the negative gender gap from the 1930s to the 1940s cohorts, since then we see no sign of convergence. These findings are very similar for all active scholars and for the ‘top five’ scholars.

Figure 2b illustrates the breakdown by scholars in ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ fields. In ‘feminine’ fields, no significant gender gap exists either for all scholars or for the ‘top five’ scholars. Conversely, scholars in ‘masculine’ fields show a significant negative gender gap with no signs of convergence across cohorts, regardless of prominence.

Figure 2 Gender gaps in publications

Notes: Panel (a) shows the gender gap in the number of publications over an academic career of at most 24 years by cohort for two different samples according to author prominence: (1) all active scholars (continuous line) and (2) ‘top five’ scholars (discontinuous line). Panel (b) shows the gender gap in the number of publications over an academic career of at most 24 years by cohort for two different samples according to prominence and by field: (1) scholars in ‘feminine’ fields (in red): scholars who have a strictly higher number of publications in top-field journals categorised as ‘feminine’ (JPubE, JDE, JHE, JOLE); and (2) scholars in ‘masculine’ fields (in blue): scholars who have a strictly higher number of publications in top field journals categorised as ‘masculine’ (JF, JET, JE, JME). We stop in the 1996 cohort to allow for an academic career of 24 years.

Given that not all journals among the high-impact 36 journals are of the same quality and status, we also analyse the evolution of gender gaps by type of publication. This heterogeneity analysis shows a clear convergence of the negative gender gap in top five publications over time across cohorts, which contrasts with the increase in the negative gender gap in publications in the lower-tier journals (which excludes general interest and top field journals).

Explaining the gender gaps in publications: Lower productivity versus shorter research careers

The negative gender gaps over the academic careers documented so far could be explained by less productive careers by women (i.e. a similar number of active years but fewer publications per year than men) or by shorter academic careers by women (i.e. a similar number of published papers per year but fewer active years than men).

We find that for the cohorts who started their publishing careers in the decade of the 1930s and until the 1960s, all the gender gaps in publications are explained by women having shorter academic careers than men. For cohorts that started their careers afterwards (1970s, 1980s and 1990s), however, the gender gap remains negative and statistically significant for both all active researchers and among ‘top five’ scholars after controlling for career length. Note, nevertheless, that accounting for differences in length reduces the gap by an average of almost 70% each decade.

The remarkable gender convergence in academic career lengths across the cohorts of scholars in economics is evident in the survival analysis that we perform. The gender gap in survival rates by the third year of the academic career decreased from an approximately 40 percentage point gap among the 1930s cohorts to a much smaller 8 percentage point gap among the 1990s cohorts. Note that our dataset does not allow us to identify whether women stop publishing altogether, devoting their time to other academic tasks such as teaching or student supervision, or keep publishing working papers or in lower-tier journals that are not considered in the set of 36 high-impact journals.

Conclusion and policy implications

The persistent under-representation of women among scholars in economics is a matter of concern for researchers and institutions, who have recently started to implement measures to attract and retain women in the field.

Our analysis has documented a remarkable and steady increase in the proportion of females in each new academic cohort over the last nine decades. Yet, the representation of women today is far from parity, with only 25% of scholars who started their publishing career in 2019 being women. Our results also show that the distribution of men and women across fields is still unequal today. Women in new cohorts are increasingly concentrated in ‘feminine’ fields. The reasons and implications of this sorting remain to be understood (Belot et al. 2023).

We have also documented negative gender gaps in publications over the careers of at most 24 years across all cohorts from 1933 to 1996, showing that the gap has remained stable for cohorts in the 1950s onwards. Crucially, the negative gender gaps until the 1970s are fully explained by women having much shorter careers than men, and differences in career length explain almost 70% of the gap in the subsequent decades. Despite the radical gender convergence in career lengths across cohorts that we have witnessed over time, our results underscore the need to focus efforts not only on attracting women but also on retaining them. In this regard, the burden of children on productivity, disproportionally borne by women (Kim and Moser 2021), and the general climate in the profession, in which women report feeling less included socially or intellectually than men (American Economic Association 2019), are some of the issues that require further attention.

References

American Economic Association (2019), “AEA professional climate survey: Main findings”.

Ayarza, A and N Iriberri (2024), “Gender Gaps among Scholars in Economics: Analysis across Cohorts”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19052.

Belot, M, M Kurmangaliyeva and J Reuter (2023), “Gender Diversity and Diversity of Ideas”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 16631.

Blau, F D and L M Kahn (2017), “The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations”, Journal of Economic Literature 55(3): 789-865.

Card, D, S DellaVigna, P Funk and N Iriberri (2020), “Are referees and editors in economics gender neutral?”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(1): 269-327.

Card, D, S DellaVigna, P Funk and N Iriberri (2022) “Gender differences in peer recognition by economists”, Econometrica 90(5): 1937-1971.

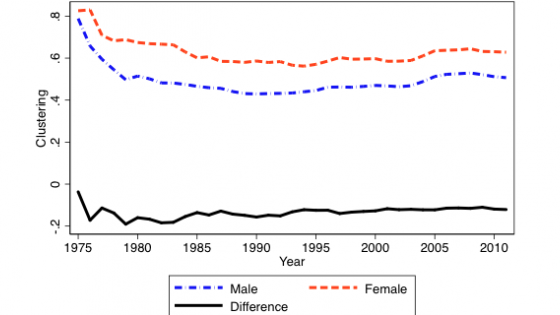

Ductor, L, S Goyal and A Prummer (2023), “Gender and collaboration”, Review of Economics and Statistics 105(6): 1366-1378 (see also the Vox column here).

Dupas, P, A S Modestino, M Niederle and J Wolfers (2021), “Gender and the dynamics of economics seminars”, NBER Working Paper No. w28494.

Goldin, C (2006), “The quiet revolution that transformed women's employment, education, and family”, American Economic Review 96(2): 1-21.

Goldin, C (2014), “A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter”, American Economic Review 104(4): 1091-1119.

Hengel, E (2022), “Publishing while female: Are women held to higher standards? Evidence from peer review”, The Economic Journal, 132(648): 2951-2991 (see also the Vox column here).

Iaria, A, C Schwarz and F Waldinger (2022), “Gender gaps in academia: Global evidence over the twentieth century”, available at SSRN 4150221 (see also the Vox column here).

Kim, S D and P Moser (2021), “Women in science. Lessons from the baby boom”, NBER Working Paper No. w29436.

Petrongolo, B and M Ronchi (2020), “Gender gaps and the structure of local labor markets”, Labour Economics 64, 101819.

Wu, A H (2020), “Gender bias among professionals: an identity-based interpretation”, Review of Economics and Statistics 102(5): 867-880.