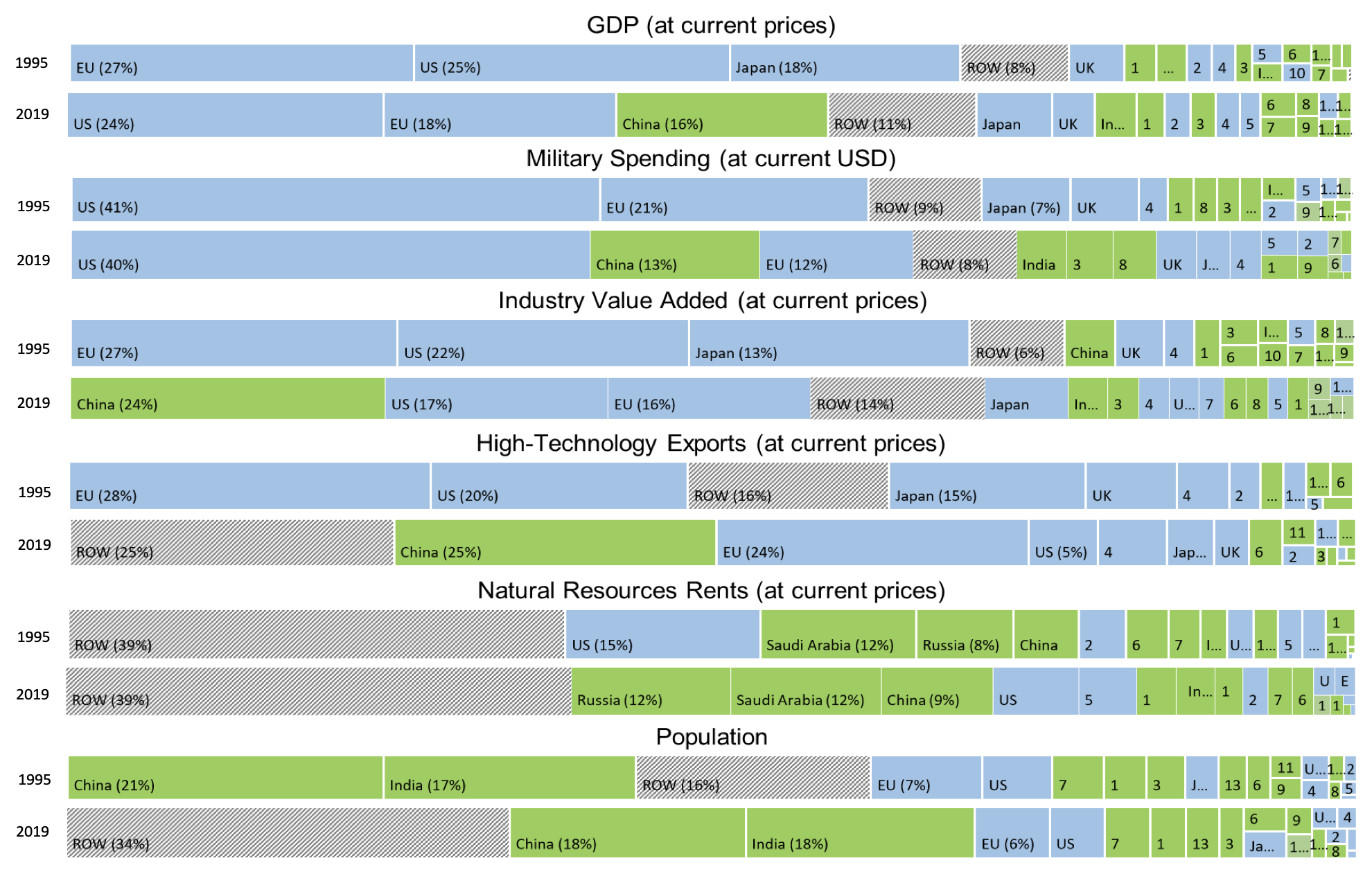

After decades of deepening global economic integration, the world has become more interconnected and interdependent, but also more diverse and multi-polar. Growing global wealth and declining extreme poverty have been accompanied by economic power shifting towards emerging and developing economies (EMDEs). In the early 1990s, Europe, the US, and Japan accounted for roughly three-quarters of global GDP; by 2019, their weight had dropped to about 50%. While advanced economies (AEs) have maintained their dominant position in the financial, high-tech, and military spheres, EMDEs account for a much larger share of global population and supply of primary commodities, as well as a growing share of global industry. China alone accounts for roughly one-third of global manufacturing value added. While trade and FDI patterns have mirrored these economic shifts, global governance has not.

Figure 1 The global economic system, 1995 versus 2019 (percent of total, AEs in blue, EMs in green)

Sources: World Bank and IMF staff calculations

Note: Industry comprises value added in mining, manufacturing, construction, electricity, water, and gas. Value added is the net output of a sector after adding up all outputs and subtracting intermediate inputs.The estimates of natural resources rents (oil, gas, coal, and other minerals) are calculated as the difference between the price of a commodity and the average cost of producing it. This is done by estimating the price of units of specific commodities and subtracting estimates of average unit costs of extraction or harvesting costs. These unit rents are then multiplied by the physical quantities countries extract or harvest to determine the rents for each commodity. The labels are Brazil (1), Canada (2), Russia (3), Korea (4), Australia (5), Mexico (6), Indonesia (7), Saudi Arabia (8), Turkiye (9), Switzerland (10), Thailand (11), Argentina (12), Nigeria (13), EU shown excl. UK.

Déjà vu?

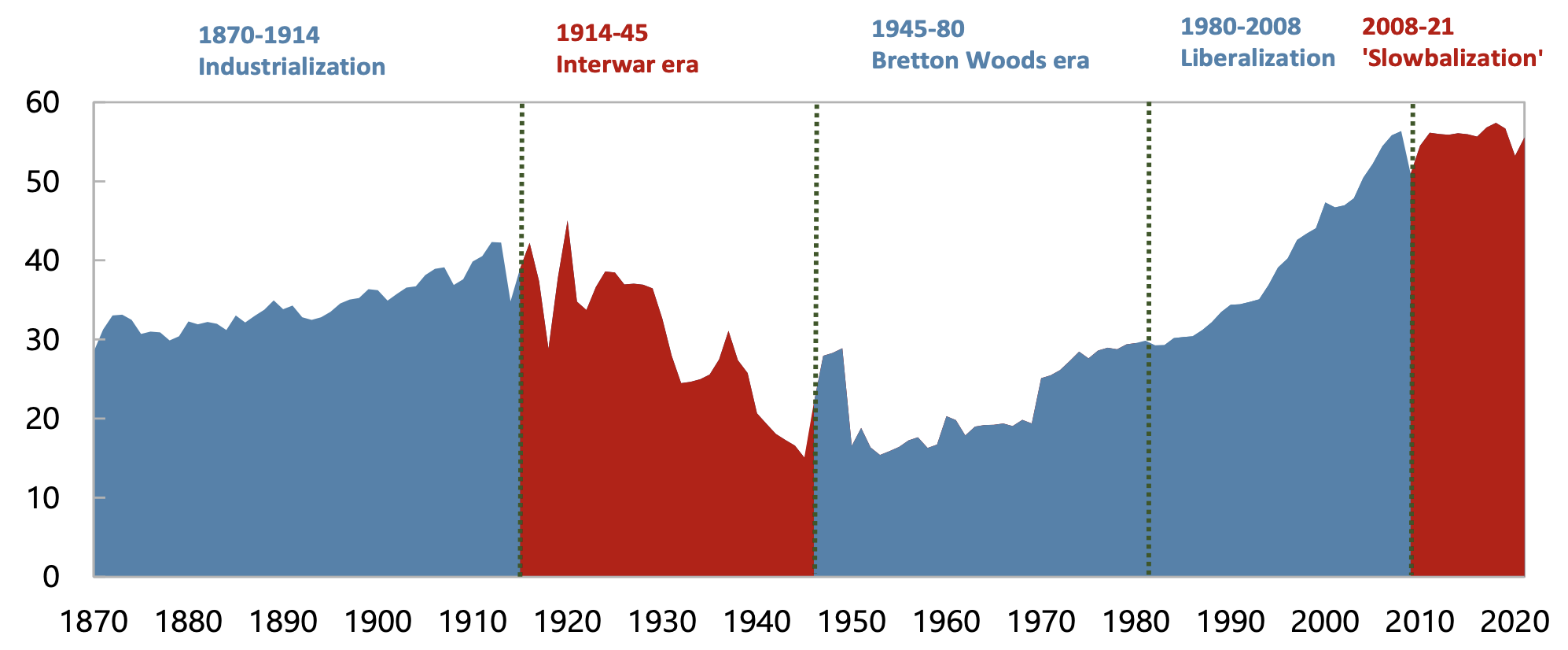

The world has been through the ups and downs of globalisation before (Figure 2).

The strains on the global economic system became apparent during the Global Financial Crisis and have worsened with the intensification of geopolitical tensions over the war in Ukraine and the US-China high-tech rivalry. When geopolitics becomes a factor in economic decision-making, countries can go to great lengths to protect their national or economic security, as we saw during the interwar period of 1914–45. The current environment feels eerily similar. With concerns about energy security, food security, the resilience of global supply chains, and securing minerals for the energy transition coming to the forefront, countries seem to be increasingly willing to manage these risks through protectionist policies that may harm others.

Figure 2 Trade openness, 1870–2021 (sum of exports and imports, percent of GDP)

Sources: Jordà -Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory Database; Penn World Data (10.0); Peterson Institute for International Economics; World Bank; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Sample composition changes over time.

The key question is how to avoid runaway fragmentation (which would make everyone worse off), while preserving policy space for countries to address legitimate security concerns and gradually rebuilding trust in international cooperation.

A pragmatic multilateralism

The rules-based multilateral system needs to adapt to the changing global economy. While the current system is not well suited for managing multi-polarity, major reforms of multilateral mechanisms may not be feasible given acute geopolitical tensions and a ‘trust’ deficit. What is the best way forward?

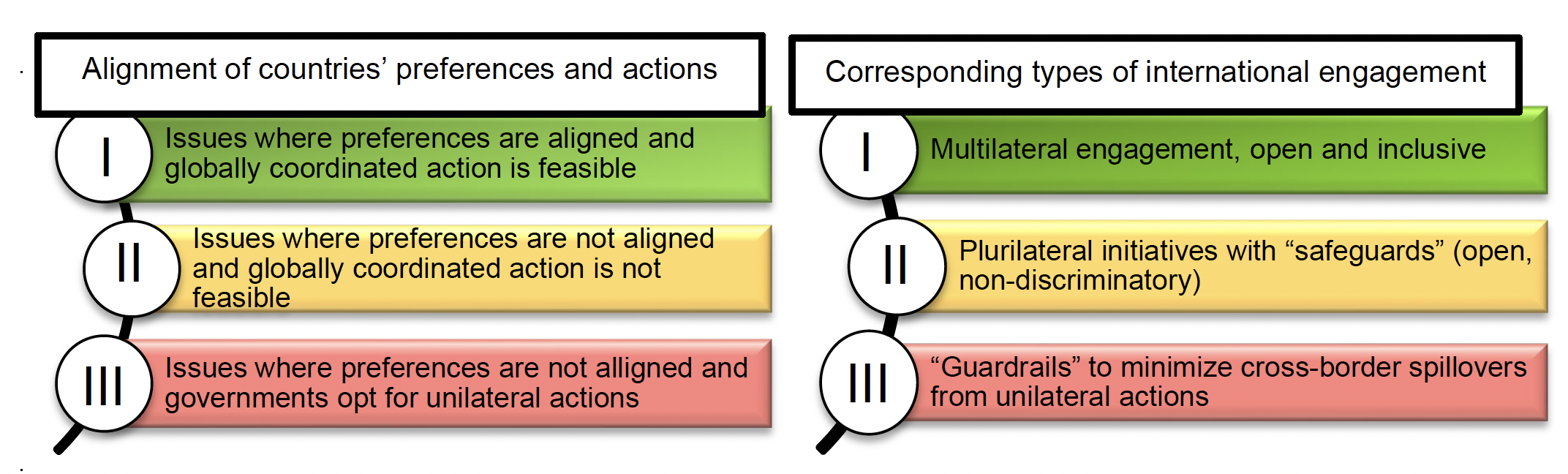

Aiyar et al. (2023) outline a pragmatic approach based on the idea that countries should remain engaged, but that specific forms of engagement should be calibrated based on the extent of alignment of countries’ preferences and actions (see Figure 3):

- In areas of common interest – such as climate change mitigation, food security, pandemic preparedness and debt issues – multilateral effort is the best and only way to make progress.

- When multilateral negotiations stall, open and non-discriminatory plurilateral initiatives (fewer countries wanting to do more) could be a practical way forward. Agreements are ‘open’ when members keep an open-door policy for others who are willing and able to commit to the same rules and norms of conduct, and ‘non-discriminatory’ when members do not discriminate between different foreign producers or service providers. Such safeguards are needed to prevent a slide towards fragmentation.

- But when countries opt for unilateral actions, credible ‘guardrails’ are needed to mitigate global spillovers and protect the vulnerable. Examples of ‘guardrails’ could include multilateral platforms for consultations on policy measures that might entail economic costs for other countries, and developing commonly agreed norms of conduct such as agreements on ‘safe corridors’ to ensure a minimum level of cross-border flows in critical goods or services.

Figure 3 A pragmatic approach to international cooperation

Sources: IMF staff

How could this approach be applied in practice?

Consider global trade. Key contentious issues include trade-distorting practices (such as industrial subsidies and market access barriers), the increasing use of trade policy for non-trade objectives (such as national security, labour protections and climate change mitigation), and the dispute settlement impasse at the WTO. Finding an agreement on all these issues, while desirable, is challenging given the diverse WTO membership, increasing complexity of trade policy, and heightened geopolitical tensions. What can be done?

- Multilateral efforts should focus on areas where countries are broadly aligned. A recent positive example is provided by the 12th Ministerial Conference of the WTO in July 2022, where a range of measures were agreed, including the exemption of World Food Program purchases from export restrictions and a partial five-year waiver from WTO intellectual property rules for COVID vaccines.

- Open and non-discriminatory plurilateral initiatives – such as WTO Plurilateral Agreements – could focus on areas where multilateral negotiations have stalled, such as industrial subsidies, market access barriers, FDI, services, anbd trade in environmentally friendly goods.

- ‘Guardrails’ are needed to mitigate the damage from unilateral actions that could lead to runaway fragmentation. One example is the US Inflation Reduction Act and similar measures adopted by other countries that could snowball into a subsidy race. To mitigate this risk, a recent joint paper by the IMF, OECD, World Bank and WTO proposed a consultation framework on the use of subsidies. This could include (1) improved data and information sharing; (2) a deeper analysis of subsidies to identify their economic impact, including cross-border spillovers, and to explore alternative approaches to better meet public policy objectives while reducing the negative effects on trading partners; and (3) an informed inter-governmental dialogue. Over time, such a dialogue could help develop international rules and norms on the appropriate use and design of subsidies. Similar processes could be considered for technology transfer requirements, data regulations, and other trade measures that are increasingly being put in place by countries to protect national security or economic security.

While the direction of globalisation remains uncertain, the world is likely to become more multi-polar (Ash et al. 2023). Hence, deeper reforms of multilateral rules and mechanisms may eventually be needed to ensure stability. Our hope is that pragmatic multilateralism can help mitigate the risk of runaway geo-economic fragmentation today.

References

Aiyar, S, J Chen, C Ebeke, R Garcia-Saltos, T Gudmundsson, A Ilyina, A Kangur, S Rodriguez, M Ruta, T Schulze, J Trevino, T Kunaratskul and G Soderberg (2023), “Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism”, IMF Staff Discussion Note No. SDN/2023/01.

Obstfeld, M (2020), “Globalization Cycles”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 14378.

IMF, OECD, World Bank and WTO (2022), “Subsidies, Trade, and International Cooperation”, Analytical Note No. 2022/001.

Ash G T, I Krastev and M Leonard (2023), “United West, Divided from the Rest: Global Public Opinion One Year into Russia’s War on Ukraine”, European Council for Foreign Relations Policy Brief, February.