Business cycle fluctuations are associated with large ups and downs of the labour market (see Shimer 2005 for the US). The increased probability of losing a job and the reduced probability of finding a job in a recession may be considered as one of the major costs of an economic downturn. Nevertheless, there is only very limited knowledge of cross-country differences of labour market dynamics over the business cycle. Most economists probably expect that – due to rigidities on the German labour market – the business cycle volatility of the labour market is smaller in Germany than in the US. However, our research shows that the opposite is true. A comparison of the labour market in Germany and in the US (from 1980 to 2004) shows that the business cycle volatility of the labour market in Germany is about twice as large as in the US. At the same time worker flows are much lower in Germany than in the US (this phenomenon has been labelled as sclerosis). We argue that sclerosis and large labour market volatilities are two sides of the same coin.

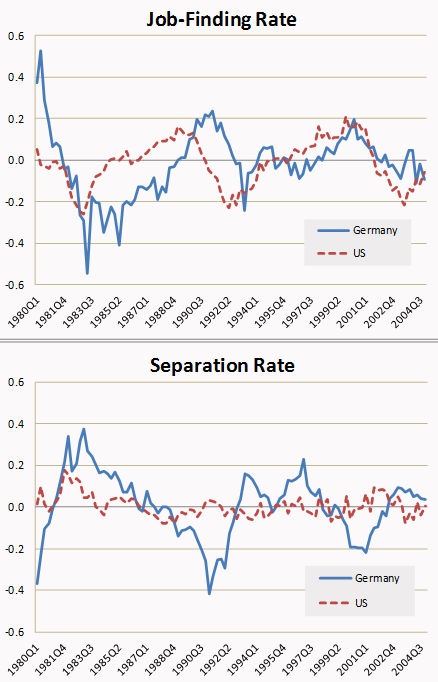

Figure 1 shows the business cycle behaviour (calculated as log-deviations from the HP-trend) of the job-finding rate and the separation rate in West Germany (constructed from the IAB-Employment Sample, IABS) and in the US (from Shimer 2005) from 1980 to 2004. Visual inspection immediately suggests that labour market volatility in Germany is more substantial.

Figure 1. Job-finding rate and separation rate in West Germany and in the US

Notes: Quarterly data, seasonally adjusted using censusX12, log-deviation from HP-trend with =105, log(X/Xhp). 1980 to 2004; the job-finding rate for West Germany is computed with IABS data as exits from unemployment divided by unemployment, the separation rate is entries into unemployment divided by employment. See Gartner et al. (2012). For US data, see Shimer (2005) and http://sites.google.com/site/robertshimer/research/flows.

Table 1 shows that the standard deviation of the job-finding rate and the separation rate is indeed substantially larger in Germany than in the US. The same is true for unemployment, vacancies, and the market tightness (i.e. the ratio of vacancies to unemployment). Interestingly, the larger volatilities are not driven by larger output fluctuations. The second line shows that the standard deviation of labour market variables relative to the standard deviation of the output rather amplifies the differences, i.e. the German labour market is roughly twice as volatile as the US labour market. The result is robust when we compare to productivity instead of output (see third line in Table 1) or when different data definitions are used (see e.g. Gartner et al. 2009, Nordmeier 2012, or Jung and Kuhn, 2010).

Table 1. Volatility of labour market variables in Germany and in the US

| |

Unemployment |

Vacancies |

Tightness |

Job-finding rate |

Separation rate |

Output |

Productivity |

| WEST GERMANY |

| Standard deviation |

0.234 |

0.349 |

0.649 |

0.159 |

0.153 |

0.025 |

0.013 |

| Relative to output |

9.451 |

14.072 |

26.203 |

6.408 |

6.166 |

1.000 |

|

| Relative to productivity |

17.878 |

26.618 |

49.565 |

12.122 |

11.664 |

|

1.000 |

| UNITED STATES |

| Standard deviation |

0.155 |

0.205 |

0.356 |

0.112 |

0.052 |

0.027 |

0.016 |

| Relative to output |

5.643 |

7.498 |

13.014 |

4.098 |

1.896 |

1.000 |

|

| Relative to productivity |

9.479 |

12.595 |

21.859 |

6.883 |

3.184 |

|

1.000 |

Notes: Quarterly data, seasonally adjusted using censusX12, log-deviation from HP-trend with =105, log(X/Xhp). 1980 to 2004; West German data: unemployment according to ILO; vacancies was provided by the Employment Agency, tightness (=vacancies/unemployment), the job-finding rate is computed with IABS data as exits from unemployment divided by unemployment, the separation rate is entries into unemployment divided by employment, output and labour productivity per worker does not include farming or public and social services and is provided by the Statistical Office. US data: see Shimer (2005) and http://sites.google.com/site/robertshimer/research/flows.

Our recent research (Gartner et al. 2012) provides a model that shows that low worker flows and large labour market volatilities are two sides of the same coin. The reason is that low worker flows generate long-term worker-firm relationships. When the economy is hit by a persistent aggregate (productivity) shock, this has a larger effect on firms’ present values under long-term relationships. Why? Imagine an economy with one period worker-firm relationships (e.g. all workers quit after one period). In this economy, only the contemporaneous aggregate productivity changes are relevant for the firm’s contemporaneous behaviour. By contrast, if workers quit very infrequently (i.e. workers stay within the same firm for several periods), expected future productivity is also relevant, i.e. the present value of a firm is affected more substantially by a persistent shock. Thus, under long-term relationships firms hiring and firing reacts more sensitively to macroeconomic shocks (for an analytical proof, see Gartner et al. 2012).

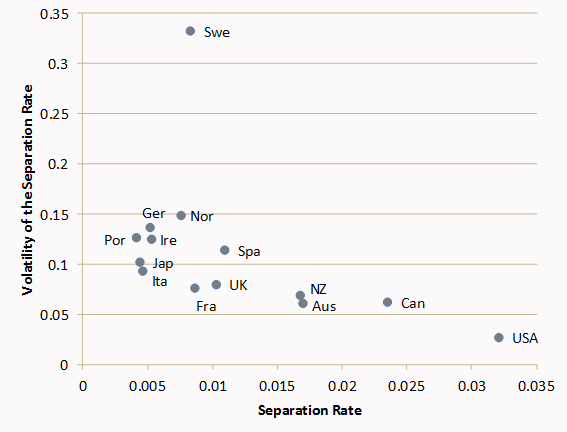

It would be interesting to test this hypothesis in a quarterly and comparable cross-country dataset. Due to a lack of fully suitable data, we rely on the dataset by Elsby et al. (2009). Figure 2 shows that the longer the average worker-firm relation (i.e. lower separation rate) in a country the higher is the business-cycle volatility of the separation rate. The correlation between these two variables is -0.48 (significance level: 6%). When we exclude the outlier, Sweden, the correlation increases to -0.82 (significance level: 1%), i.e. there is some tentative support for our hypothesis.

Figure 2. Cross-country evidence

Note: Source Elsby et al. (2009), average monthly rates, 1988-2007, calculated on yearly basis, = 100 for the HP-filter.

This column has argued that sclerosis and large volatilities may be two sides of the same coin. The connection is clear-cut in theory. The data for Germany and the US from 1980 to 2004 support this story and cross-country evidence points into the same direction. Obviously, the labour market experience in Germany and in the US during the Great Recession (2008/2009) tells a completely different story as the volatility of the labour market in Germany was small (i.e. (un)employment was basically flat). But, as Gartner and Merkl (2011) argue, this may be due to a transition period in Germany caused by the labour market reforms and the ensuing wage moderation. The trend of declining equilibrium unemployment was offsetting the effect of the adverse macroeconomic shock. There are signs that the transition period is coming to an end. Germany may be back to normal soon. Thus, we expect that future recessions are associated with job losses again.

References

Elsby, M, B Hobijn, and A Sahin (2009), “Unemployment dynamics in the OECD”, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper No. 04/2009.

Gartner, H and C Merkl (2011), “The roots of the German miracle”, VoxEU.org, 9 March.

Gartner, H, C Merkl, and T Rothe (2009), “They are even larger! More (on) puzzling labour market volatilities”, Kiel Working Paper 1545.

Gartner, H, C Merkl, and T Rothe (2012), “Sclerosis and large volatilities: two sides of the same coin”, Economics Letters, 117(1):106-109.

Jung, P and M Kuhn (2010), “Explaining cross-country labor market cyclicality: U.S. vs. Germany”, mimeo.

Nordmeier, D (2012), “Worker flows in Germany: inspecting the time aggregation bias”, IAB Discussion Paper 12/2012. Nuremberg.

Shimer, R (2005), “The cyclical behavior of equilibrium unemployment and vacancies”, American Economic Review, 95(1):25-49.