Analytical background

In a survey of work on quantifying global production sharing in recent years, Antràs (2013: 6) calls the value-added exports to gross export ratio, or the VAX ratio – as proposed by Johnson and Noguera (2012) – “the state of the [art]” and “an appealing inverse measure of the importance of vertical specialization in […] world production”. We will suggest that the VAX ratio concept needs to be improved in two important ways.

First, the VAX ratio, as currently defined in the literature, is not well-behaved at the sector, bilateral, or bilateral sector level. At any of these disaggregated levels, there is no guarantee that the value added exports are less than gross exports. As a result, the ratio is not bounded by one. The key to understanding this point is a distinction between a forward-linkage-based measure of value-added exports (VAX_F), which includes indirect exports of a sector’s value-added via gross exports from other sectors of the same exporting country, and a backward-linkage-based measure of value-added exports (VAX_B), which is value-added from all sectors of a given exporting country embodied in a given sector’s gross exports.

For example, a forward-linkage-based measure of value-added exports in the US electronics sector includes that sector’s value-added embodied in US gross exports from automobile and chemical sectors, but excludes the value-added contributions from these sectors embodied in the gross exports of US electronics. In comparison, a backward-linkage-based measure of US value-added embodied in US electronics exports includes value-added contributions from other US sectors such as services and automobiles to the production of US electronics gross exports, but excludes the value-added contributions from the US electronics sector to the gross exports of other sectors such as US automobiles..

Such a distinction is critical for having a well-behaved ratio of value added/gross exports at the country/sector levels. Only when the value added is based on backward linkages would it be able to guarantee that the VAX_F/gross exports is between zero and one (as long as gross exports are positive). The VAX ratio in the existing literature is based on forward linkages, and does not have this property.

Note that at the country aggregate level, the distinction between the backward and forward linkages disappears. At that level, the VAX ratio as defined in the literature coincides with ours.

Second, even when the VAX ratio is redefined based on backward linkages, it still misses some of the important features of international production sharing. Consider a hypothetical example in which both the US and Chinese electronics exports to the world have an identical ratio of value-added exports to gross exports (say, 50% for each), but for very different reasons. In the Chinese case, the VAX ratio is 50% because half of the Chinese gross exports reflect foreign value-added (say value-added from Japan, Korea, or even the US). In contrast, for the US exports, half of the gross exports are US value-added in intermediate goods that return to the U.S. after being used by other countries to produce their export goods. So only half of the US value-added that is initially exported is ultimately absorbed abroad – the US VAX ratio is 50% even if it does not use any foreign value-added in the production of its electronics exports. In this example, while China and the US occupy very different positions in the global value chain, the two countries’ VAX ratios would not reveal this important difference.

A new gross trade accounting framework

To provide such additional information, one needs to go beyond extracting value-added trade from gross trade statistics by identifying which parts of the official data are double counted, and what the structure and sources of the double counting are. This objective is achieved by the gross trade accounting method we have developed in Wang et al. (2013). This transparent trade accounting tool not only provides a full decomposition of gross trade flows at any disaggregated level, but also offers analytical results that are able to guide the ways in which well-behaved summary statistics of cross-country production sharing and double counting can be defined.

Our major analytical results on summary measure of value-added trade can be summarized as follows:

- In a world of three or more countries, domestic value-added in exports that is absorbed abroad (DVA), forward-linkage-based value-added exports (VAX_F), and backward-linkage-based value-added exports (VAX_B), are, in general, not equal to each other at the bilateral/sector level. These value-added trade measures are only equal at the country aggregate level. VAX_F and VAX_B are equal at the bilateral aggregate level, while DVA and VAX_B are the same at the country/sector level.

- DVA at the sector level is always less than or equal to the sector-level gross bilateral exports. Therefore, the ratio of domestic value-added absorbed abroad to gross exports has an upper bound of one at any level of disaggregation as long as gross exports are positive.

- VAX_B at the sector level is always less than or equal to the country’s sector-level gross exports. Therefore, the ratio of VAX_B to gross exports has an upper bound of one at the country/sector level when gross exports are positive.

- VAX_F is always less than or equal to sector-level value-added production. Therefore, the ratio of VAX_F to GDP by sector has an upper bound of one.

The intuition behind these statements is simple: since direct value-added exports at the sector level are the same for both value-added export measures, only indirect value-added exports at the sector level may be very different. The indirect value-added exports in the forward-linkage-based measure are the sector’s value-added embodied in other sectors’ gross exports, which has no relation to the gross exports from that sector. Therefore, the value-added exports to gross exports ratio defined by Johnson and Noguera (2012) at the sector level is not desirable, since its denominator (sector gross exports) does not include the indirect value-added exports from other sectors. It is common in the data for some sectors to have very little or no gross exports, but their products are used by other domestic industries as intermediate inputs, and thus they can have a large amount of indirect value-added exports through other sectors. In such cases, the VAX ratio will become very large or infinite. Similarly, at the bilateral level, due to indirect value-added trade via third countries, two countries can have a large volume of value-added trade even when they have little or no gross trade. Therefore, value-added exports to gross exports ratio as defined in the literature is not upper bound at one and cannot be used as an inversed summary measure of double counting at the bilateral and sector level. However, because such indirect value-added exports are part of the total value-added created by the same sector, the forward-linkage-based value-added exports to GDP ratio can be properly defined at the sector level.

In Wang et al. (2013), we propose to use the share of domestic value-added that is absorbed abroad (DVA) in gross exports as a summary measure of value-added content and (1-DVA) as summary measure of double counting at the bilateral, sector, or bilateral sector level. This measure is conceptually meaningful at any level of disaggregation when gross exports are positive.

Empirical application 1: Tracing the structure of vertical specialisation across countries and over time

Vertical specialisation (VS), defined as foreign contents in a country’s gross exports, is a summary statistic to measure international production sharing. It has been widely used in the literature (e.g. Hummels et al. 2001 and Antràs 2013). However, as shown by our gross trade accounting diagram in part 1 of this essay, there are different components within VS, and each has different economic meanings and represents different types of cross-country production sharing arrangement. For example, a large share of foreign value added in a country’s final goods exports (FVA_FIN for short) may indicate that the country mainly engages in final assembling activities based on imported components and just participates in cross-country production sharing on the low end of a global value chain, while an increasing foreign value-added share in a country’s intermediate exports (FVA_INT for short) may imply that the country is upgrading its industry to start producing intermediate goods for other countries, especially when more and more of these goods are exported to third countries for final goods production. The latter is a sign that the country is no longer at the bottom of the global value chain.

Pure double counting of foreign value-added in a country’s exports (FDC for short) can only occur when there is back-and-forth trade of intermediate goods. An increasing FDC share in VS indicates the deepening of cross-country production sharing. In other words, it suggests that intermediate goods cross national borders by an increasing number of times before they are used in final goods production. Therefore, knowing the relative importance of these components and their changing trend over time in a country’s total VS can help us to gauge the depth and pattern of cross-country production sharing, and to discover major drivers of the general increase of VS in a country’s gross exports over time.

As shown in Table 1, across all countries and all sectors, the total foreign content (VS) sourced from manufacturing and services sectors used in world manufacturing goods production has increased by 8.3 percentage points (from 22.5% in 1995 to 30.8% in 2011 – see column 3). Interestingly, the information on VS structure reported in the last three columns indicates that the net increase is mainly driven by an increase in FDC. This suggests that the international production chain is getting longer: over time, a rising portion of trade reflects intermediate goods made and exported by one country, used in the production of the next-stage intermediate goods and exported by another country, to be used by yet another country down the chain to produce yet another intermediate good. This increase in trade in intermediate goods that cross national borders multiple times is what causes the rising share of FDC.

Table 1. Average vertical specialisation structure of world manufacturing industries

|

Year

|

Gross exports

|

VS share in gross exports

|

% of VS

|

|

FVA_FIN

|

FVA_INT

|

FDC

|

|

1995

|

4,020,202

|

22.5

|

45.5

|

34.9

|

19.5

|

|

2000

|

4,916,605

|

26.5

|

45.7

|

32.2

|

22.2

|

|

2005

|

7,850,625

|

29.9

|

42.3

|

32.5

|

25.1

|

|

2007

|

10,472,405

|

31.6

|

40.7

|

32.4

|

26.9

|

|

2009

|

9,093,710

|

28.4

|

43.3

|

33.4

|

23.2

|

|

2010

|

10,878,662

|

30.3

|

41.7

|

33.6

|

24.7

|

|

2011

|

12,458,263

|

30.8

|

40.6

|

34.5

|

25.0

|

Because the share of foreign value added in final goods exports in total VS has declined by about 5 percentage points during the same period (from 44.5% in 1995 to 40.6% in 2011), and because the share of foreign value added in intermediate goods exports in total VS stayed almost constant, the increase in VS share in world manufacturing exports is driven mainly by an increase in FDC share (from 19.5% in 1995 to 25% in 2011). If this trend continues, the FDC share may reach the level of the FVA share and become an important feature of cross-country production sharing. If we add the shares of FVA_INT and FDC, these two components involving intermediate goods trade have already accounted for about 60% of the total manufacturing VS in 2011.

There is noteworthy heterogeneity in the VS structure both across countries and across sectors, especially between industrialised and developing economies. As an example, Table 2 reports total VS and its structure in electrical and optical equipment exports for six Asian economies: Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, India, and Indonesia. The three industrialised Asian economies are reported in the right panel. Despite the difference in the level of their total VS shares, their VS structure is very similar – lower and declining in FVA_FIN, relatively stable in FVA_INT, and rapidly expanding in FDC.

Taiwan’s VS structure is an informative example (presented in the bottom-right cells of Table 2). Taiwan is an important supplier of parts and components, and often occupies several different positions on the global production chain (since it produces both inputs into chip making and memory chips themselves). This is reflected in the fact that the collective shares of FDC and FVA_INT have exceeded 80% of Taiwan’s total VS (or 40% of its gross exports) since 2005.

In comparison, for other developing Asian countries such as China, India, and Indonesia (presented in the left panel of Table 2), the share of FVA_FIN still accounts for about 50% of their total VS until 2011. There are also interesting differences among these three Asian giants. For China, the VS structure change during the 17 years was mainly driven by a decline in FVA_FIN and an increase in FDC, while FVA_INT stayed relatively stable. For Indonesia, it was driven by a rapid expansion of both FVA_INT and FDC – both by more than 10 percentage points, indicating a rapid upgrading of Indonesia’s electrical and optical equipment industries. Finally, for India, a latecomer in joining the international production network, the share of FVA_FIN rose (from 38.2% in 1995 to 52.8% in 2011) and the FVA_INT share continued to decline (from 40.2% in 1995 to 25.3% in 2011), while the FDC share stayed relatively stable over the last 17 years. This might be resulted from a strategic shift from import substitution to export-oriented development; it is also consistent with a move from the upstream portion of the production chain to a more downstream position, as China and Indonesia did decades ago. This empirical evidence indicates that the structure of VS – in addition to its total sums – offers additional information about each country’s respective positions on the global value chain.

Table 2. VS structure of electrical and optical equipment exports for selected Asian economies

Year

|

Gross Exports

|

VS share in Gross Exports

|

% of VS

|

Gross Exports

|

VS share in Gross Exports

|

% of VS

|

|

FAV

_FIN

|

FVA

_INT

|

FDC

|

FAV

_FIN

|

FVA

_INT

|

FDC

|

|

China

|

Japan

|

|

1995

|

34,032

|

22.1

|

56.9

|

27.5

|

15.6

|

124,265

|

6.7

|

44.6

|

34.8

|

20.6

|

|

2000

|

68,998

|

25.9

|

54.0

|

23.9

|

22.1

|

136,123

|

9.5

|

43.5

|

29.5

|

27.0

|

|

2005

|

296,936

|

37.6

|

52.3

|

24.4

|

23.3

|

143,324

|

11.8

|

35.5

|

31.4

|

33.1

|

|

2010

|

638,982

|

29.3

|

50.4

|

27.0

|

22.7

|

162,861

|

14.9

|

34.0

|

35.1

|

30.8

|

|

2011

|

721,417

|

28.9

|

50.2

|

27.7

|

22.1

|

166,935

|

16.0

|

33.1

|

37.5

|

29.4

|

|

India

|

Korea

|

|

1995

|

1,260

|

10.9

|

38.2

|

40.2

|

21.6

|

40,639

|

27.8

|

30.0

|

43.7

|

26.3

|

|

2000

|

1,927

|

17.8

|

41.7

|

32.2

|

26.1

|

60,434

|

35.1

|

40.3

|

30.9

|

28.7

|

|

2005

|

5,962

|

20.1

|

42.3

|

30.2

|

27.5

|

102,595

|

34.6

|

31.0

|

31.2

|

37.9

|

|

2010

|

23,994

|

19.0

|

54.1

|

24.0

|

21.9

|

147,823

|

36.9

|

24.8

|

39.3

|

36.0

|

|

2011

|

29,470

|

19.4

|

52.6

|

25.3

|

22.1

|

159,191

|

36.8

|

26.4

|

40.6

|

33.0

|

|

Indonesia

|

Taiwan

|

|

1995

|

2,831

|

28.7

|

70.2

|

19.1

|

10.7

|

41,818

|

43.8

|

40.2

|

39.1

|

20.7

|

|

2000

|

7,637

|

30.6

|

53.6

|

23.3

|

23.1

|

77,861

|

44.8

|

41.0

|

31.3

|

27.6

|

|

2005

|

8,387

|

29.7

|

43.6

|

26.8

|

29.6

|

100,957

|

49.0

|

22.2

|

32.8

|

45.0

|

|

2010

|

11,666

|

29.0

|

46.5

|

28.1

|

25.3

|

142,943

|

49.1

|

15.8

|

40.2

|

44.0

|

|

2011

|

12,558

|

30.7

|

48.1

|

29.1

|

22.8

|

147,646

|

48.2

|

17.4

|

41.7

|

40.9

|

Note: VS is sourced from manufacturing and services sector only.

Empirical application 2: VAX_B and VAX_F

We use the German business services sector to illustrate the difference between these two concepts.

By the backward linkages, we look at German value added from a recipient or importing country’s perspective (user perspective). It measures German domestic value-added embedded in its business service exports from all German sectors that produce inputs used in the production of German business service exports. Columns 2–5 of Table 3 provide a backward-linkage-based decomposition. In particular, DVA is the domestic value-added from all sectors in Germany that is embedded in its business service sector exports that are ultimately absorbed abroad. Unsurprisingly, all the other terms, RDV, FVA, and PDC are relatively small. The DVA is about 93% of the gross exports for that sector.

By the forward linkages, we adopt a producer’s perspective and look at German value-added originated in its business service industry but is exported either directly by the service sector or indirectly by other German sectors. For example, if German automobile exports use German business services, that constitutes indirect exports of value-added from the German business services sector. This particular piece of German value added is a part of the forward-linkage-based exports of value-added from the German service sector (although it is also part of a backward-linkage exports of German value-added embedded in German automobile gross exports).

Table 3. German business services exports (WIOD sector 30)

Year

(1)

|

TEXP

(2)

|

Backward looking (Share)

|

Forward looking (Ratio)

|

DVA

(% of (2))

(3)

|

FVA

(% of (2))

(4)

|

RDV

(% of (2))

(5)

|

PDC

(% of (2))

(6)

|

VAX_F

(% to (2))

(7)

|

RVA_F

(% to (2))

(8)

|

|

1995

|

14,725

|

92.9

|

2.7

|

3.2

|

1.3

|

377.3

|

7.4

|

2000

|

19,597

|

91.4

|

3.8

|

2.8

|

2.0

|

344.0

|

6.8

|

2005

|

43,240

|

92.5

|

3.8

|

2.0

|

1.7

|

293.2

|

5.2

|

2007

|

58,061

|

92.0

|

4.0

|

2.1

|

1.9

|

291.1

|

5.1

|

2009

|

59,629

|

92.5

|

3.4

|

2.3

|

1.8

|

278.7

|

4.8

|

2010

|

59,814

|

92.6

|

3.9

|

1.8

|

1.7

|

282.8

|

4.3

|

|

2011

|

62,854

|

92.4

|

4.0

|

1.8

|

1.8

|

291.6

|

4.7

|

If a sector does a lot of indirect exports of its sector-originated value-added via other sectors, the forward-linkage-based measure of value-added exports can in principle exceed that sector’s direct gross exports, because indirect exports of that sector’s value-added are not part of that sector’s gross exports. This is indeed the case for the German business services sector. German exports in other sectors commonly embed value-added that is originally from the German business services sector. As we see in column 7 of Table 3, as a result, the forward-linkage-based measure of value-added exports from the German business services sector is often 280% to 377% of the sector’s gross exports. (In contrast, the backward-linkage-based measure of total domestic value-added in a sector’s gross exports is bounded between 0 and 100%.)

These two measures at the sector level are useful for different purposes. If one wishes to understand the fraction of a country-sector’s gross exports that reflects a country’s domestic value-added, one should look at VAX_B for that sector, which by our decomposition formula is DVA = gross exports - FVA - RDV - PDC. If one wishes to understand the contribution of all value-added from a given sector to the country’s aggregate exports, one should look at the VAX_F.

As pointed out in Koopman et al. (2014), domestic value-added in a country’s exports and value-added exports are, in general, not equal. The former only looks at where the value-added is originated, regardless of where it is ultimately absorbed, whereas the latter refers to the subset of domestic value-added in a country’s exports that are ultimately absorbed abroad. Our gross trade accounting framework also allows us to distinguish forward-linkage-based value-added exports measure (VAX_F) from GDP by industry in a sectors’ gross exports, which also includes a forward-linkage-based measure of domestic value-added in a given sector but finally returns home (RDV_F), in addition to VAX_F. This difference is particularly important for countries located at the top of a global value chain – we report some selected industry examples from our decomposition results below.

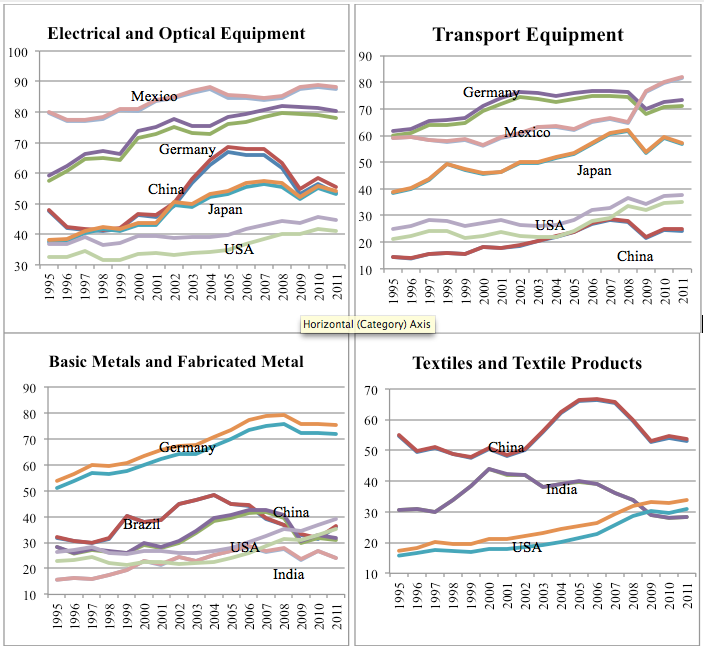

Figure 1 plots the time trend of the value-added exports (VAX_F) to GDP ratio and the domestic value-added in exports to GDP ratio (both of which are forward-linkage-based) for four selected industries based on estimates from the World Input-Output Database. These graphs show clearly that domestic value-added in exports to GDP ratios are constantly higher than sector value-added exports to GDP ratios, especially for advanced economies. For instance, the difference between these two ratios is around 4%, 5%, and 4% of sector total value-added for the US, and 3.5%, 2.5%, and 2% for Germany in basic metal, electric and optical equipment, and transportation equipment industries, respectively, during the 17 years of our sample period. Even in the textile and textile product industries, there is also a consistent 2–3% difference between these two ratios for the US and Germany during the same period. In comparison, the difference between these two ratios for most developing countries is generally tiny.

Figure 1. The difference between the value-added exports to GDP ratio and the domestic value-added in exports to GDP ratio

Concluding remarks

The gross trade accounting method we develop in Wang et al. (2013) is a useful tool for economics and trade policy analysis. It generalises all previous attempts in the literature on this topic and corrects some conceptual errors. Importantly, it goes beyond simply extracting value-added exports from gross exports, and recovers additional useful information about the structure of international production sharing at a disaggregated level that is hidden in official trade data.

Estimating value-added exports can be accomplished by directly applying the original insight of Leontief (1936). It does not require the decomposition of international intermediate trade flows. Recovering additional information on the structure of international production sharing from official statistics requires going beyond a simple application of Leontief’s insight, and finding a way to decompose international intermediate trade itself into value-added and double-counted terms at a disaggregated level, which has never been done (correctly) before in the literature. The additional structural information can be used to develop a measure of a sector’s position in an international production chain that also varies by country. Of course, the list of possible applications goes beyond these examples.

By applying this disaggregated decomposition framework to bilateral sector gross trade flows among 40 trading nations in 35 sectors from 1995 to 2011 in the WIOD database, we produce a sequence of large panel datasets that can be used by other researchers for a variety of topics. For example, we show how one could use our decomposition results to meaningfully trace the structural changes in the widely used measure of vertical specialisation, initially proposed by Hummels et al. (2001), over time; and how to distinguish a forward-linkage-based measure of domestic value-added exports from a sector (that indirectly exports its value-added through other sectors’ gross exports) from a backward-linkage-based measure of value-added exports (that includes the value-added contributions from other domestic sectors).

It is our hope that this gross trade accounting method and the datasets generated by applying the method could provide a useful tool and data source for other researches in the international trade community to study variety issues that relate to cross-country production sharing and global value chains.

References

Antràs, Pol (2013), Firms, Contracts, and Global Production, CREI Lectures in Macroeconomics, Chapter 1.

Johnson, Robert, and Guillermo Noguera (2012), “Accounting for Intermediates: Production Sharing and Trade in Value-added”, Journal of International Economics, 86: 224–236.

Hummels, D, J Ishii, and K Yi (2001), “The Nature and Growth of Vertical Specialization in World Trade”, Journal of International Economics, 54: 75–96.

Koopman, R, Z Wang, and S-J Wei (2012), “Estimating domestic content in exports when processing trade is pervasive”, Journal of Development Economics, 99(1): 178–189.

Koopman, R, Z Wang, and S-J Wei (2014), “Tracing Value-added and Double Counting in Gross Exports”, American Economic Review, 104(2): 459–494. Also available as NBER Working Paper 18579.

Leontief, W (1936), “Quantitative Input and Output Relations in the Economic System of the United States”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 18: 105–125.

Mattoo, A, Z Wang, and S-J Wei (2013), Trade in Value Added: Developing New Measures of Cross-border Trade, Washington DC: CEPR and World Bank.

Timmer, M (ed.) (2012), “The World Input-Output Database (WIOD): Contents, Sources and Methods”, WIOD background document, April.

Wang, Z, S-J Wei, and K Zhu (2013), “Quantifying International Production Sharing at the Bilateral and Sector Levels”, NBER Working Paper 19677, November.