Health systems across many parts of the world are increasingly managed, funded, and regulated by regional governments, with federal or central governments playing a role in the coordination of care and in managing global public goods and other responsibilities such as drugs pricing. A decentralised health system is regarded as more efficient given its effect on policy experimentation and diffusion, as well as its effect on government competition at the same or a different level (Salmon 2019, Breton 1996, Costa-Font and Rico 2006).

Previous Vox columns have documented evidence that federalism can improve the public provision of childcare (Giorcelli et al. 2022) and environmentally friendly attitudes (Tovar Jalles and Mello 2022), as well as health system satisfaction (Costa-Font 2012). However, during pandemics it is less clear whether decentralisation is the most efficient choice. In Europe, the management of the Single Market could be disrupted in a pandemic, which might call for a European-wide authority (Costa-Font 2020) to avoid nationalistic reactions. Besides Single Market access, which the last pandemic showed can be disrupted by collective action problems, what is the most efficient governance of the health system during a pandemic? How should coordination of the health system take place? Should central government take over from regional or state governments and impose a ‘command and control’ approach, or should the health system still be run regionally with a central-level coordination role.

Theoretically, it is unclear whether regional autonomy offers an advantage in the face of a pandemic, especially when the political effects are uncertain, as was case during the first wave of COVID-19. The main advantage of decentralised coordination is that, even when directed by the central government, it provides incentives for information sharing and experimentation. Coordination allows rapid exchange of information on the characteristics of the pathogen, the collection of comparable data, and the actions of infected patients to be managed, thus preventing the virus from spreading further.

The territorial governance of the health system was at the core of policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially the balance of power between highly centralised and a more decentralised coordination. Although the management of the pandemic requires the highest level of intergovernmental coordination possible, for this coordination to occur, the exchange of critical information and local knowledge about the needs of the health system are needed.

Spain and Italy: Similar healthcare models but different governance during the pandemic

To empirically study the effects of centralisation, in a recent paper (Angelici et al. 2023) we compare the results of the hierarchical centralisation implemented in Spain during the first wave of the pandemic with the decentralised coordination strategy implemented in Italy and in federal management models, where expertise in healthcare regulation rests with regional governments. Italy and Spain share similar institutional frameworks and similar, decentralised healthcare systems, but adopted different governance models during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the Spanish constitution defines the circumstances for a "state of emergency", the Italian constitution only allows the national government to legislate by temporary decree in cases of "necessity and urgency", without defining which level of government is to take the initiative. For this reason, the governance of the health system in Italy was driven by informal cooperation and co-governance – that is, the regions did not oppose a central role of state leadership. In contrast, the central government in Spain did not attempt to implement any form of co-governance during the first wave of the pandemic and adopted a more hierarchical and centralised approach.

Both Spain and Italy were hit hard by the pandemic at roughly the same time – Spain was only a few weeks behind Italy in the spread of the virus. Given the different governance responses to the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak, the comparison of evidence from Italy and Spain can be informative of the balance of territorial power allocation and, specifically, of the welfare effects of health care centralisation/decentralisation. Hierarchical centralisation by the central government can exclude bottom-up coordination and information sharing.

Spain and Italy are probably the two health systems in Europe that are most similar, which makes them particularly suitable for comparative analysis. In fact, the healthcare system in Spain is comparable to the Italian one in all its relevant design features: it is organised along the lines of a national health system and the governance of the system is decentralised at the regional level. Seventeen regions of Spain and twenty regions of Italy have a constitutional right to health responsibilities, including provider organisation and resource allocation. The evidence to date indicates that decentralised governance plays a role in reducing regional inequalities in the use of health and in stimulating innovation (Costa-Font 2012). So, what can we say about the effects of health centralisation on mortality and other outcomes?

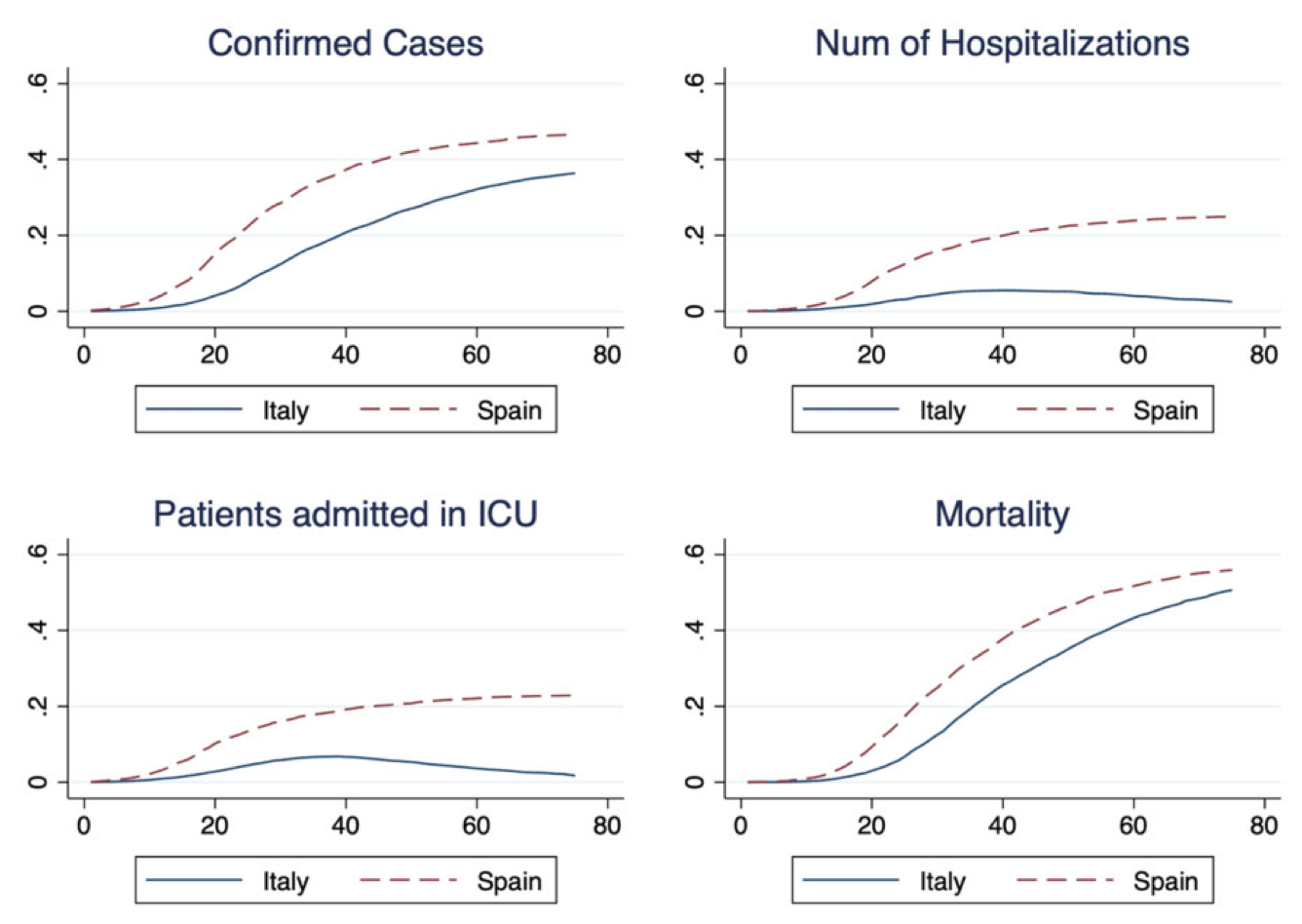

Figure 1 shows the cross-country comparisons of the measures related to COVID-19 examined: numbers of cases and deaths from COVID-19 (outcome measures), and hospitalisations and ICU admissions (measures of health system outcomes that can explain the above results). We rely on nationally aggregated figures and all measures are population-standardised rates. The results indicate that although Spain has a population of about 47 million people, compared to about 60 million people in Italy, it recorded a higher number of confirmed cases, hospitalised patients, patients admitted to the ICU, and deaths. While hospitalisations and ICU admissions decreased after 30 days in Italy, they continued to grow in Spain. This descriptive evidence points to better performance by a governance model that allows for regional differentiation of policies.

Figure 1 Evolution of COVID-19 first wave in Italy and Spain

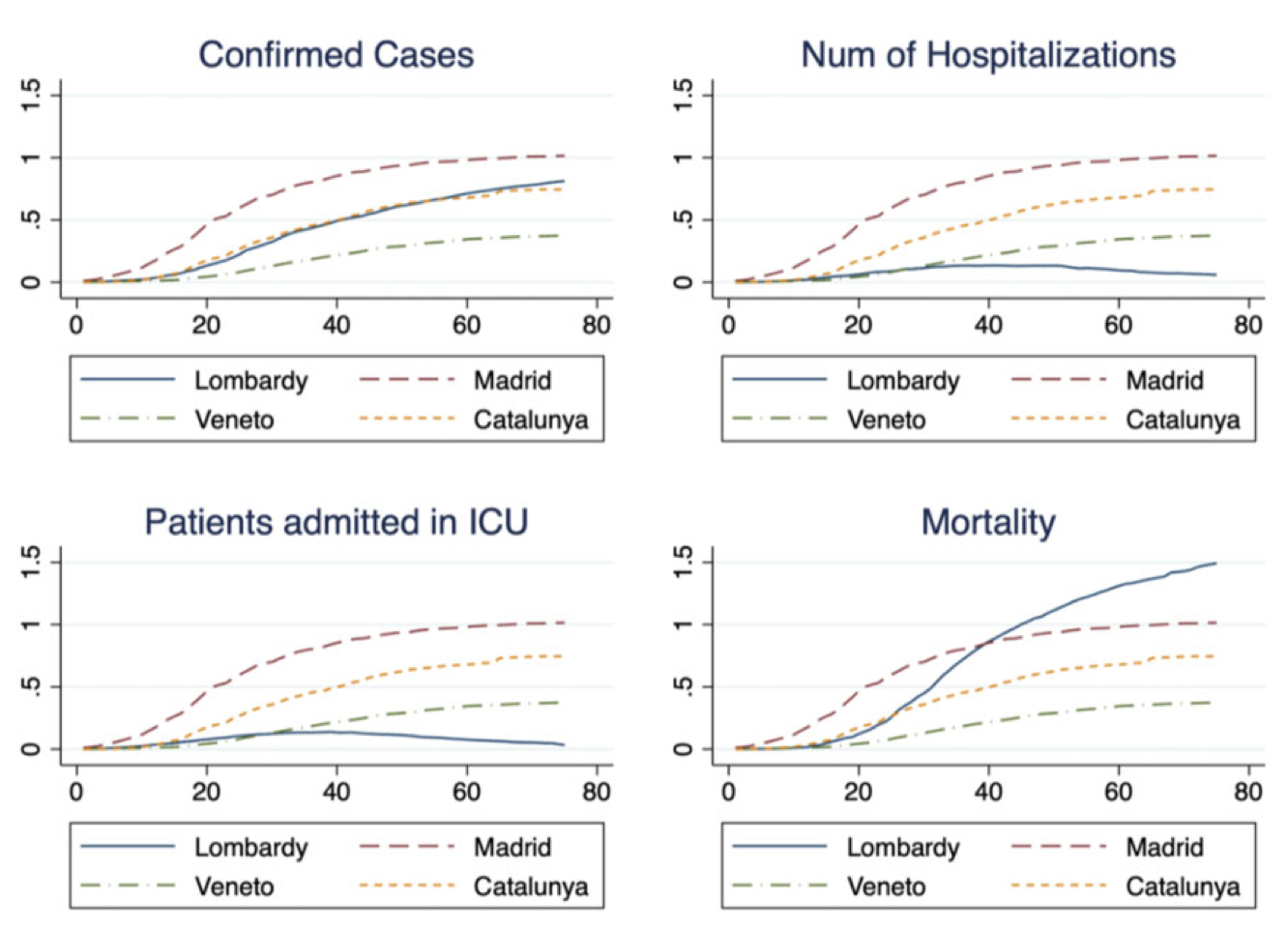

To better understand the role of regional patterns, we can look at regional trends. In Italy, we focus on Veneto and Lombardy due to the different model of integrated management (Levaggi et al. 2020); in Spain, we focus on Madrid and Catalonia. Madrid was the epicentre of the crisis in Spain, and while Catalonia requested a complete closure of its borders along with a whole range of social distancing measures, the declaration of a state of emergency gave the central government increased and new powers over health services. The panels in Figure 2 compare the four regions of the two countries, standardising all measures of population in each region. The trends in the two Spanish autonomies are clearly below those of Lombardy and Veneto. In addition, while Lombardy shows different performance from Veneto, Madrid and Catalonia exhibit similar trends. In terms of mortality, Lombardy exhibits a much higher figure than all the other regions. Again, the trend in Madrid is very similar to the trend in Catalonia, while Veneto follows a very different pattern compared to Lombardy. These trends are consistent with the differential role of regional autonomy in Veneto and Lombardy, compared to the much more centralised management of the crisis in Spain.

Figure 2 Evolution of COVID-19 first wave in four regions in Italy and Spain

So, looking forward…

One interpretation of our results is that in an environment where the optimal response to a pandemic is unknown, as as the case with the first wave of COVID-19, decentralised coordination makes a difference. These estimates support the idea that there is a penalty to centralisation when information sharing is crucial, and that experimentation is important to address specific regional needs and to produce policy information that can be used across the country. In Italy, intergovernmental tensions emerged only in the second wave, when it became clearer how to manage the virus.

That said, it is worth noting that the strategic reactions and tensions that emerged in the second and subsequent waves were different from those in the first wave, which is why we focus here only on the first wave. In Italy, intergovernmental tensions emerged during the second wave, when it became clearer how to manage the virus. In contrast, in Spain regional governments become more proactive after the first wave.

However, one could argue that Italy, and possibly Spain, would have enjoyed a more successful policy response if they had followed Veneto’s model of a more integrated healthcare system, where private providers work in coordination with the rest of the healthcare system, thus reducing costs and allowing for the exchange of information and coordination. These estimates could point to the need for more policy learning beyond the borders of European countries, possibly in the form of some European-level platform, supporting a future European health union, as discussed in Costa-Font (2020).

References

Angelici, M, P Berta, J Costa-Font and G Turati (2023), “Divided We Survive? Multilevel Governance during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy and Spain”, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, pjad002.

Breton, A (1996), Competitive Governments, Cambridge University Press.

Costa-Font, J (2020), “The EU needs an independent public health authority to fight pandemics such as the COVID-19 crises”, VoxEU.org, 2 April.

Costa-Font, J (2012), “Healthcare decentralisation improves satisfaction and equity at no additional cost”, VoxEU.org, 22 August.

Costa-Font, J and A Rico (2006), “Vertical competition in the Spanish national health system (NHS)”, Public Choice 128(3-4): 477-498.

Giorcelli, M, E M Martino, and N Bianchi (2022), “Fiscal decentralisation can improve women’s labour outcomes”, VoxEU.org, 24 February.

Levaggi, R, G Turati and J Costa-Font (2020), “The effectiveness of managed competition during pandemics: Evidence from Covid-19”, 20 September.

Salmon, P, (2019), Yardstick competition among governments: accountability and policymaking when citizens look across borders, Oxford University Press.

Singer, G and L Sager (2022), “Decentralisation and the environment: Attitudes and policy”, VoxEU.org, 25 April.