We all know of professors who like teaching but prefer to do research. How does our department make sure we put the right effort into our classes? Our neighbours want us to be clean, even when we might want to tidy our yards later. How can neighbours enforce civility while remaining civil? These situations represent a classic problem in social science. When people face choices that benefit themselves at a cost to others, how do we structure incentives so people do the right thing?

Some have suggested that monitoring by peers can be enough (Ostrom et. al. 1992, Fehr and Gachter 2000). In particular, individuals can punish each other – the good teachers can snub the bad teachers, the clean tenants can scold the messy tenants. And if that doesn’t work, they can resort to other forms of vigilantism.

Economists have examined punishment by peers in laboratory studies by allowing punishment between group members. Peer punishment has been shown to increase good behaviour, but often makes the group as a whole worse off. Vigilante justice is just too costly – people punish too much. When these studies add realism by allowing people to punish repeatedly (Nikiforakis 2008), the result is revenge, feuds, and often devolution of the social order. Punishment by peers only makes things worse.

Hired guns from the Wild West

How often do we see vigilante justice used to enforce good behaviour by others? Instead small groups seem to appoint or hire someone with “authority” to enforce the social order. Just as in the Wild West when vigilantes were replaced with hired guns, schools have department heads who review teaching evaluations, and apartment buildings have superintendents to track complaints. These delegated authorities have the responsibility to discipline those who fall short of good behaviour. But this leaves unanswered a critical question. If we delegate authority to a hired gun, how should they govern? Monitoring everyone and punishing all cheaters is difficult and costly. We need and enforcement method a simple, low cost, has small penalties, and works.

How? Imagine a 1 minute race, where the person who runs the second farthest gets $100. How would this race end? Poetically, it ends at the beginning. Everyone will be standing with toes on starting line, but nobody will cross. Why? Crossing the line starts you in first place, and no one will ever want to pass you.

More realistically, think of driving on the highway. You want to go fast but avoid a ticket. If there is at least one car going faster than you, the highway patrol will ticket the faster car. You’re safe if you are the second fastest car. If no one wants to get a speeding ticket, then everyone will try to be the second biggest speeder. Everyone drops back, leapfrogging each other until they’re all behind the line, that is, they’re all going the speed limit. And, in real life, when a police car is on the road typically everyone swarms behind it. To enforce the speed limit, the officer need only fine the first driver who passes the police car.

We use this intuition to design our enforcement device.

The hired gun versus peer punishment

In recent research (Andreoni Gee 2011a, 2011b) we investigate whether a delegated authority – the hired gun – that punishes only the largest deviators can effectively enforce socially desirable outcomes. We also compare the effectiveness of this hired gun to vigilante or peer punishment. Can a delegated authority replace costly and inefficient peer punishment and get superior social outcomes?

We represent the social dilemma by the public goods game. Each person is assigned to a group of 4 people and given 5 tokens to divide between a socially beneficial public good (like teaching well, or being a good neighbour) and a private good benefiting only themselves (like being a lazy teacher or messy tenant). Each token spent on the public good pays a return of $2 to all group members. This means the group as a whole earns $8 (4 people times $2 each). Each token spent in the private good, by contrast, pays a return of $3 to only the individual who made the choice. No other group member benefits. A purely selfish person will choose to spend all 5 of their tokens on the private good, making $3 on each, and none in the public good. If all the group members do that, then they will each earn $15 (5 tokens at $3 each). However, a group taking the socially optimal action would instead spend nothing in the private good, and each spend all 5 tokens in the public good for a payoff of $40 per group member (5 tokens from each of 4 group members for a total of 20 tokens in the public good each worth $2).

We add the ability to delegate punishing authority using the hired gun. The hired gun identifies the group member who gave the lowest number of tokens to the public good (like the fastest car on the highway). The hired gun fines this player just enough so that they would rather have been the second largest deviator. In our experiment, this means we punish the biggest cheater so they earn what the second biggest cheater earns, then take one more token away. Now they would have preferred to have been the second biggest cheater.

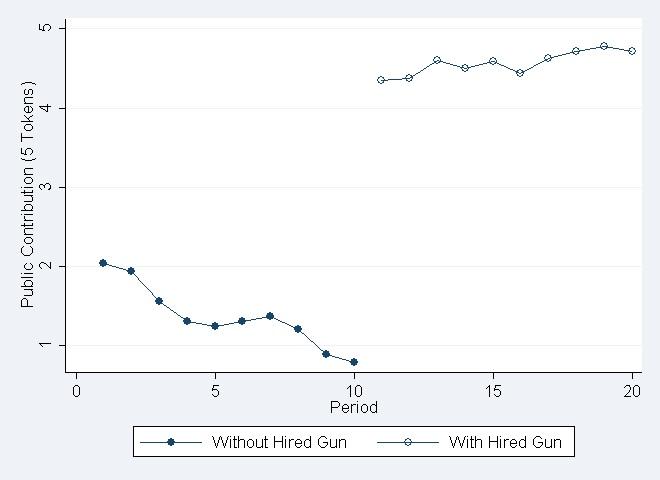

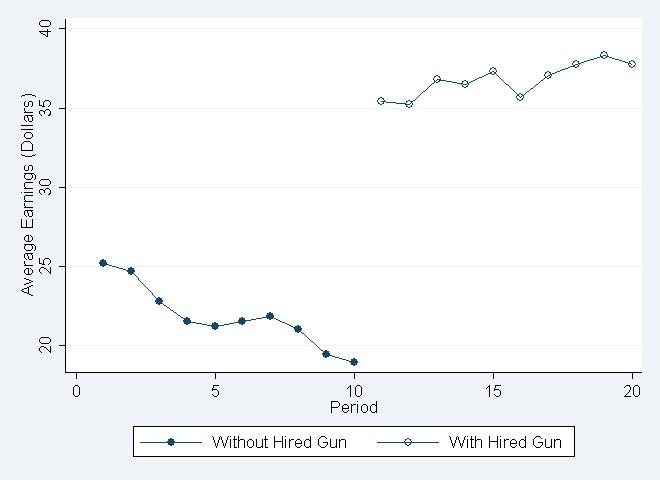

In our first study people repeated the public goods game 10 times, and then repeated it 10 more times with a hired gun. To prevent reputations, choices were made on a computer in anonymous, random groups that changed each time. As shown in Figure 1, players spend an average of only 1.3 tokens on the public good when there is no hired gun, but they raised their contributions to 4.5 tokens when there is a Hired gun. This is a 68% increase in average earnings, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Average tokens contributed to the public good out of a possible 5 tokens

Figure 2. Average earnings per person per period

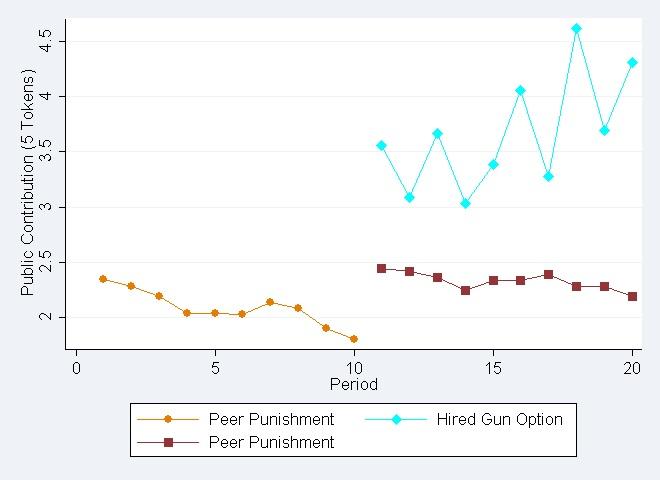

Clearly the hired gun mechanism had the desired effect of starting a race for second place. To understand if this was a superior mechanism to peer punishment we ran a second study. Here we allowed players to pay a price to fine one another after they played the public goods game. This type of vigilante justice is akin to a tenant in the apartment complex penalising their messy neighbour by, for instance, complaining to them in person.

In this second study subjects played a public goods game with the ability to punish their peers. After 10 periods of only peer punishment, some groups were given the chance to pay a fee to get a hired gun. The players paid for the hired gun over 70% of the time, and as can be seen in Figures 3 and 4 it was well worth the cost.

Figure 3. Average tokens contributed to the public good out of a possible 5 tokens

Figure 4. Average earnings per person out of a possible $41

It is clear from Figure 3 that the option to have a hired gun causes people to give more to the public good. In turn Figure 4 illustrates the huge increase in money earned.

When the hired gun option is available, people stop using peer punishment. Just as someone won’t complain personally to messy neighbours, but instead directs complaints to the superintendent, when hired guns are available people stop using vigilantism to enforce good behaviour.

The main message of our research is that when things aren’t working, people are clever enough to invent methods, like a hired gun, to help them achieve better outcomes.

Direct punishment by peers is one option, but it only makes things worse. Instead, we show that delegating punishment that creates a “race for second place” is far more effective and, moreover, pushes out vigilantism.

So, let the races begin!

References

Andreoni, James and Laura K. Gee (2011), “The Hired Gun Mechanism”, UCSD working paper, and NBER Working Paper 17032.

Andreoni, James and Laura K Gee (2011), “Gun For Hire: Does Delegated Enforcement Crowd out Peer Punishment in Giving to Public Goods?”, UCSD working paper, and NBER Working Paper 17033.

Fehr, Ernst and Simon Gachter (2000), “Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments”, The American Economic Review, 90(4):980-994.

Ostrom, Elinor, James Walker, and Roy Gardner (1992), “Covenants With and Without a Sword: Self-Governance is Possible”, The American Political Science Review, 86(2):404-417.

Nikiforakis, Nikos (2008), “Punishment and counter-punishment in public good games: Can we really govern ourselves?”, Journal of Public Economics, 92(1-2):91-112.