The role of financing markets and potential sources of market failure in the allocation of funds has been studied extensively in the general finance literature (Stiglitz and Weiss 1986, Bell et al. 1990, Pagano and Jappelli 1993, Besley 1994, Aglietta and Breton 2001, Phillips 2004), and financing in the movie industry in particular (Phillips 2004, Hjort 2012, La Torre 2014, Ravid 2018). The high levels of uncertainty and the low general availability of tangible assets in the industry make US film finance an iconic case for studying the evolution of lending markets, the development of new risk devices by the private sector, and the use of alternative collateral sources.

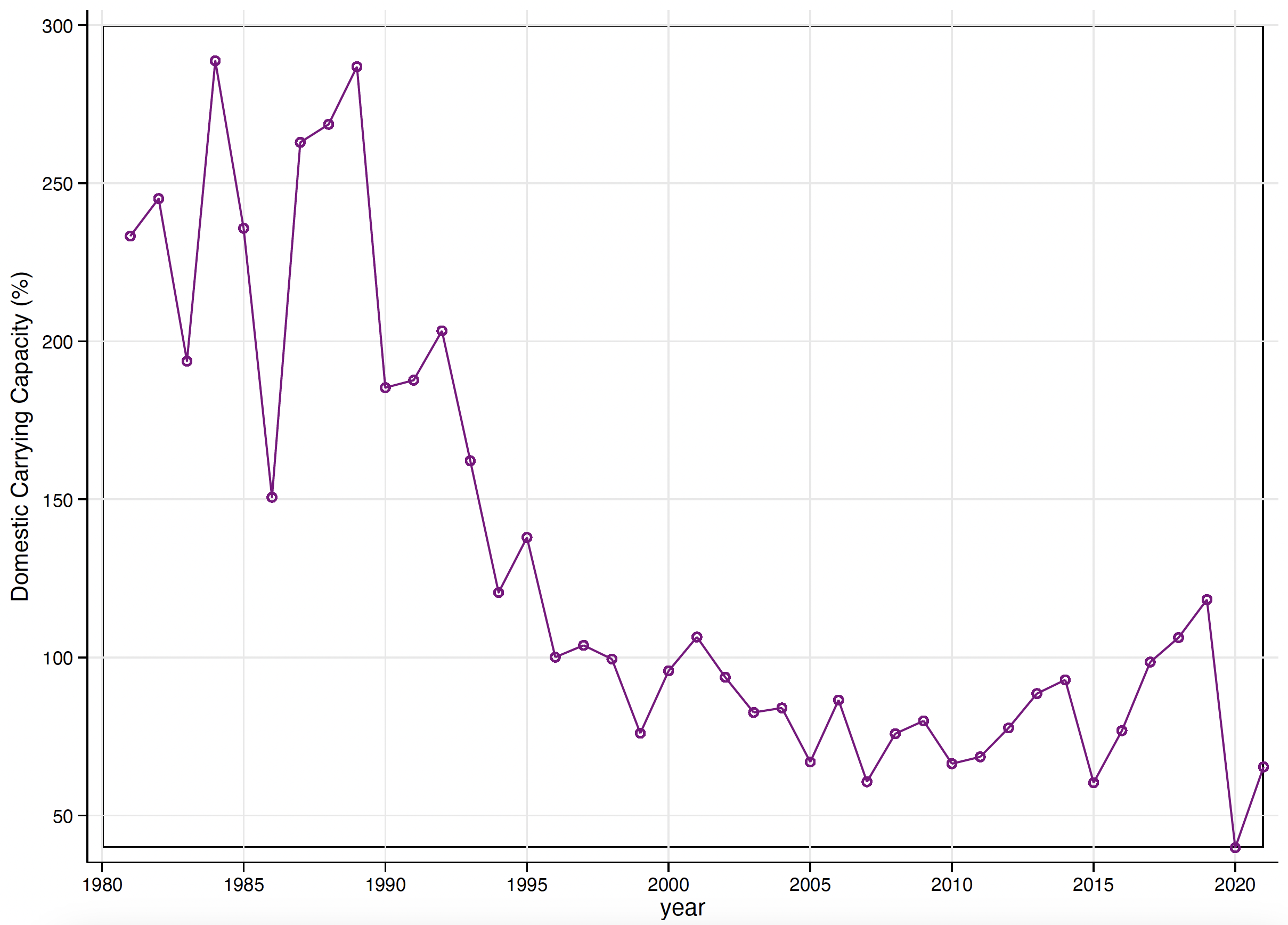

The top 1,000 highest-grossing movies in US cinemas over the last 90 years of film history generated a total US box office income of $166 billion, but required a total investment and overall production budget of $112 billion. Still, financing a new film continues to be a high-risk investment. Even blockbuster titles do not always break even and recover all costs. And many new projects are not completed and do not see a release in cinemas. Figure 1 relates domestic box office income from cinematic releases to movie production costs (reported budget). However, these ‘domestic carrying capacity’ numbers do not give the full picture. They ignore initial investment in risky projects that failed to deliver, and do not account for income streams generated from new digital channels and other advertising costs incurred beyond production. Nonetheless, they indicate that, in more recent years, the industry has been facing drastic changes, including a steep increase in average production costs and a constant decline in traditional income sources from cinematic distribution.

Naturally, key stakeholders in US film finance have found a variety of ways to make the pertaining financial and commercial risks more manageable in the sector. In a recent study (Cuntz et al. 2023), we map out the debt-financing landscape in the US and identify the most common types of financial deals in the movie industry, including innovative devices to mitigate and transfer risk between lending parties and the impact of digitisation on current film financing practices. Qualitative evidence comes from a series of semi-structured interviews, commissioned expert memoranda, and a dedicated panel held with selected industry experts from the US. Moreover, we provide descriptive evidence on credit lending and intangible collateral use in the movie industry, using close to 50,000 loan filings in the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) registers, and more than 1.1 million registered movie titles at the US Copyright Office (USCO) and used to secure loan deals in recordations.

Figure 1 Domestic carrying capacity

Note: This figure shows the yearly median domestic carrying capacity in US dollars, calculated as domestic box officeUSD/production budget∗100. N = 5, 946. More information in Cuntz et al. (2023).

Source: Data obtained from The-Numbers charts in November 2022.

What are the key actors and most common type of financial deals?

Producers, distributors, and financiers are key players in US film finance. Producers handle script acquisition and manage film development, while distributors acquire exhibition rights. Traditionally, studios dominated production and distribution, but independent streaming services now play an important role. Commercial banks with specialised film finance branches provide external financing in the form of loans to producers.

Big-budget films are often debt-financed, while independent producers usually seek project financing for one film at a time. Debt deals vary based on production stages and guarantees from third parties. Streaming platforms and larger production companies rely on corporate financing and use more complex financial instruments to minimise their risk exposure.

How to mitigate risk and the role of IP assets in deals

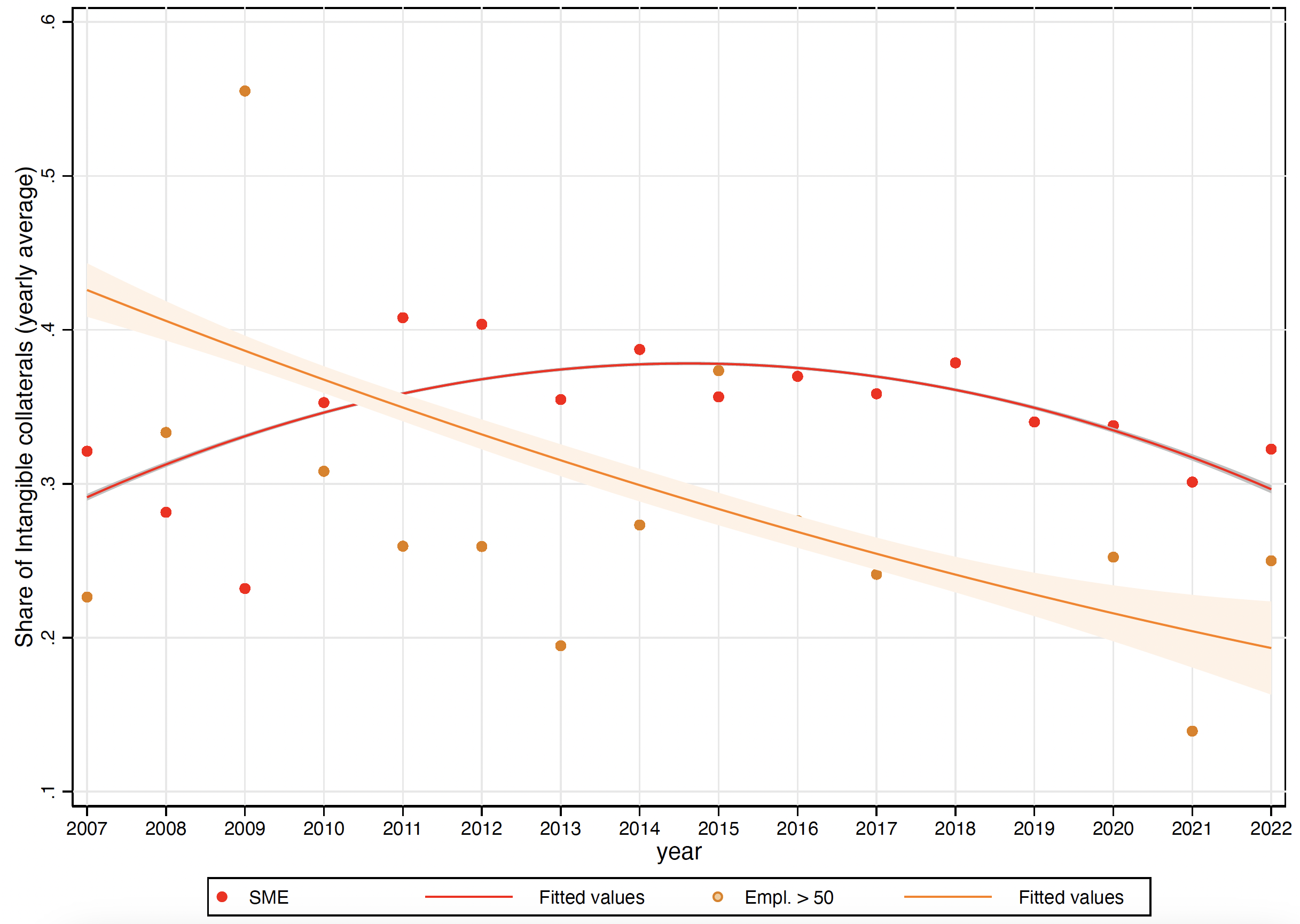

Our study suggests that intangible assets, including intellectual property (IP), play a crucial role in film financing deals, particularly for independent producers and SMEs who may have even fewer tangible assets to offer as collateral. According to the analysis of all securitised loans by the industry via the US credit transparency registers, intangibles have been used as collateral in about 35% of all industry loans (as identified by filings under SIC industry code 7812) (Figure 2). Our report provides evidence that SMEs use intangibles-backed loans more extensively than larger producers, and that intangibles account for a greater share of SME collateral.

Figure 2 UCC filings share of intangibles and employment

Note: This figure shows the share of UCC loan filings with intangibles as collateral (SIC (1) 7812) across filing statement types = originals. The figure is split in UCC loan filings across companies with less (more) than 50 employees represented by the red (yellow) line. UCC filings with ’secured party names’ from public lenders are excluded in this figure.

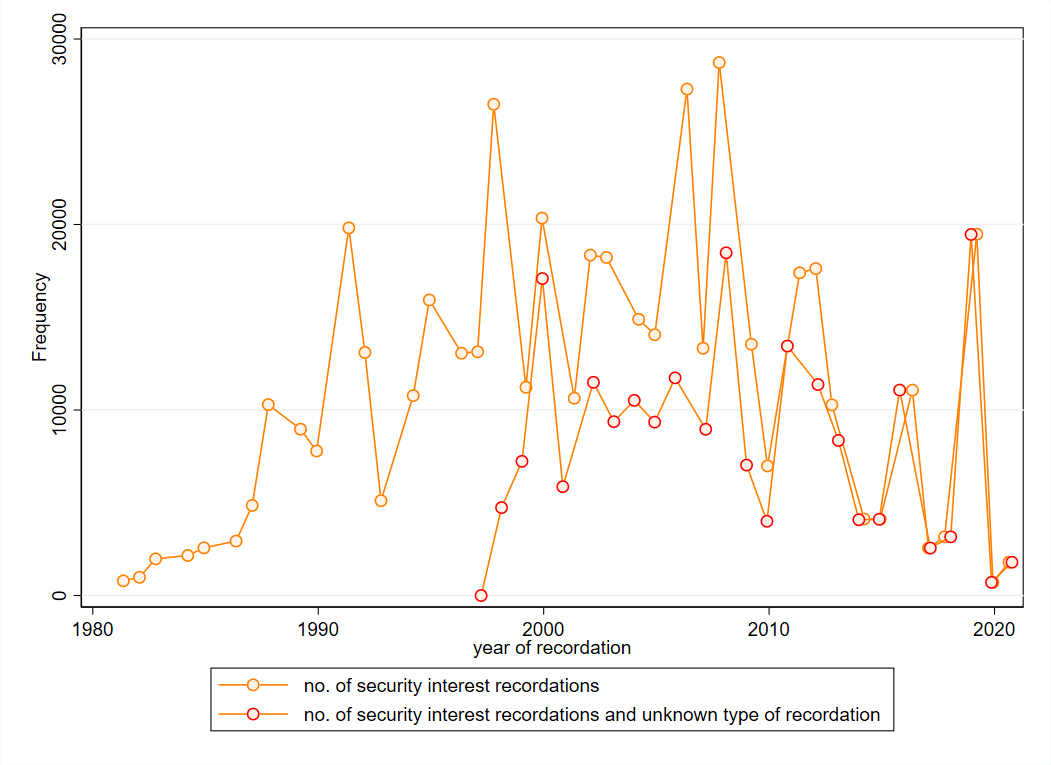

Registration and recordation records at the US Copyright Office provide another interesting source for the exploratory analysis of the US lending market. These new data published by USCO open up many potential avenues for future research on copyright-related topics in the movie industry and beyond (accessible at www.copyright.gov/policy/women-in-copyright-system/). Figure 3 provides descriptive numbers of security interests recordation around registered movie titles. Average numbers range between 5,000 and 20,000 recorded works per year, indicative of the heavy use of the register by industry stakeholders seeking funds and those financing the industry. This is also due to strong incentives at work to record and ‘perfect’ industry loans: registration and recordation allow stakeholders to establish priority in the case of credit default and can serve as evidence in court proceedings.

Figure 3 Annual number of total ‘security interest’ recordations of registered motion pictures by year of recordation, work level

Note: This figure shows the annual number of total recorded works by year of recordation and classified as ‘security interest’ recordations (or with unknown type of recordation). Recordations in the matched sample relate to registered motion pictures only.

To mitigate financial risk in film production and distribution, private-sector solutions in the sector have evolved over time. Co-production and loan syndication are two important strategies stakeholders have used to share risk. Co-production allows producers to share production and marketing costs with other producers, while loan syndication involves multiple financiers pooling their capital to finance larger loans. Negative pick-up deals transfer the risk of production to the producer, while distributors accept the risks associated with the commercial exploitation of the film. Insurance companies or completion guarantors may also insure or guarantee some risk-related aspect of film production in exchange for a fee, thereby taking up an important role in industry financing. Finally, special purpose vehicles are often used to isolate risk in film finance from corporate balance sheets, creating separate legal entities to separate film debt and revenue risk around new projects from producers' and investors’ core business. These private-sector solutions help manage the high-risk nature of film production and financing, and our study provides further details on this.

The impact of digitisation and streaming services entering the movie market

Previous research has focused on the impact of digitisation in the movie industry. For example, Benner and Waldfogel (2023) discuss decreasing costs for digital distribution, cost advantages over theatrical releases (Sorenson and Waguespack 2006), and the global shipping of local content (Aguiar and Waldfogel 2018) as basic arguments for the rise of medium-level budget and more niche film titles in catalogues. New ways to finance content making better use of IP assets, as well as new financing opportunities such as crowdfunding and ‘fresh money’ provided by streaming services entering the market, could help explain these changes and the recent supply increase observed in the film market (Waldfogel 2017).

In light of the previous research and based on interviews with industry experts, our study shows how the entry of streaming platforms has increased competition in content distribution. In the short term, this has meant that independent producers can make more money for each film and might find it easier to finance new projects. However, the tendency of streaming platforms to acquire all rights for a film (i.e. ‘full buy-out’ of rights) means that producers may forfeit all future royalty payments and thus make less money in the longer term. Similarly, as the cost of producing a film has continued to grow, studios, streaming services, and larger distributors increasingly exploit content exclusively and there is a tendency to invest in stories with a proven audience, rather than exploring truly original content and taking greater commercial risk.

Key takeaways for policymaking

Film production continues to be a high-risk venture, and the US film industry provides a interesting case for studying novel financial risk mitigation mechanisms and best practices in creative content financing. Our study indicates that IP has been widely used as collateral in US film debt finance. Additionally, co-production, loan syndication, risk indemnification, and insurance are important strategies employed by stakeholders involved in financial deals to share and transfer risk.

Our study aims to provide useful insights for policymakers. Our findings suggest that enhancing access to information regarding deals and companies involved in financial markets could increase transparency and reduce the cost of setting up future deals. Moreover, providing financial management education for young producers could help them navigate the complex landscape of film finance more effectively and lower entry barriers for them. Finally, encouraging banks and other financiers to work with smaller distributors could expand the deal options available to producers.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Intellectual Property Organization or its member states.

References

Aglietta, M and R Breton (2001), “Financial systems, corporate control and capital accumulation”, Economy and Society 30(4): 433–466.

Aguiar, L and J Waldfogel (2018), “Netflix: global hegemon or facilitator of frictionless digital trade?”, Journal of Cultural Economics 42: 419–445.

Bell, C, T Srinivasan and C Udry (1990), “Segmentation, rationing and spillover in credit markets: The case of rural Punjab”, manuscript, Yale University.

Benner, M J and J Waldfogel (2023), “Changing the channel: Digitization and the rise of ‘middle tail’ strategies”, Strategic Management Journal 44(1): 264–287.

Besley, T (1994), “How do market failures justify interventions in rural credit markets”, The World Bank Research Observer 9(1): 27–47.

Cuntz, A, A Muscarnera, P C Oguguo and M Sahli (2023), “IP assets and film finance - a primer on standard practices in the U.S”, WIPO Economic Research Working Paper No. 74.

Hjort, M (2012), Film and risk, Wayne State University Press.

La Torre, M (2014), The economics of the audiovisual industry: Financing TV, film and web, Springer Nature.

Pagano, M and T Jappelli (1993), “Information sharing in credit markets”, The Journal of Finance 48(5): 1693–1718.

Phillips, R (2004), “The global export of risk: finance and the film business”, Competition and Change 8(2): 105–136.

Ravid, S A (2018), “The economics of film financing: an introduction”, in Handbook of State Aid for Film: Finance, Industries and Regulation, pp. 39–49.

Sorenson, O and D M Waguespack (2006), “Social structure and exchange Selfconfirming dynamics in Hollywood”, Administrative Science Quarterly 51(4): 560–589.

Stiglitz, J E and A Weiss (1986), Credit rationing and collateral, Cambridge University Press.

Waldfogel, J (2017), “How digitization has created a golden age of music, movies, books, and television”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(3): 195–214.