Emerging markets (EMs) will need significant green finance in the coming years to facilitate a smooth transition towards becoming low-emission economies, a goal that is in the interest of the whole world (Bolton et al. 2022). However, they are still far from this target. A recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that to stay on track to achieve net zero by 2050, the investment needs of emerging and developing economies solely in the renewable energy sector could reach $1 trillion a year by 2030 (IEA 2021).

EMs, especially those with limited and shrinking fiscal capacity and small domestic investor bases, will have to rely heavily on foreign private investment to achieve their net zero carbon emission goals. According to estimates by the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, around 55% of the climate financing needed can be covered by private investment, 25% by Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), and 20% by other actors using innovative instruments for low-cost financing (Songwe et al. 2022).

In the context of small domestic investor bases, cross-border capital flows will be particularly important for EMs. These could include foreign direct investment (FDI) or bank lending, as well as portfolio equity and debt flows by global investors. But while FDI is growing (Knutsson and Flores 2022), it will not be sufficient on its own. Other sources of financing, and notably portfolio investment flows, will still be needed to meet EMs’ increasing financing needs (Couto 2023).

On the basis of a dataset of the largest 37,000 mutual funds at a global level, our recent OECD report delivered to the Indian G20 Presidency (OECD 2023a) provides evidence that despite the ongoing sustainable investing boom, investment funds are directing only a tiny share of their investments into green companies in EMs.

Large disconnect between the high numbers of sustainable-labelled funds and actual ‘green’ allocations in funds’ portfolios

‘Sustainable’ investing has grown rapidly in recent years, as assets under management (AUM) of sustainable funds tripled from 2010 to 2020, rising sharply to reach almost $3.2 trillion by the end of 2021 or around 6% of global AUM. This growing pool of assets could in theory be leveraged for investing in green sectors.

However, labels like ‘sustainable’ and ‘ESG’ (Pástor et al 2023, OECD 2022), or metrics focusing on climate impact or carbon emissions, may not necessarily contribute to environmental sustainability, nor come close to having an actual climate impact. Instead, in our report, we used novel definitions of ‘green companies’ as companies involved in carbon solutions (renewable energy, transport, buildings, and energy efficiency) and ‘green funds’ as funds with more than 25% of their portfolio in such companies, to better capture genuine climate impact. We found 1,600 such funds in our sample, with only $1.4 trillion of AUM and covering a limited geographic distribution.

‘Green’ investment funds are primarily domiciled and invested in the US

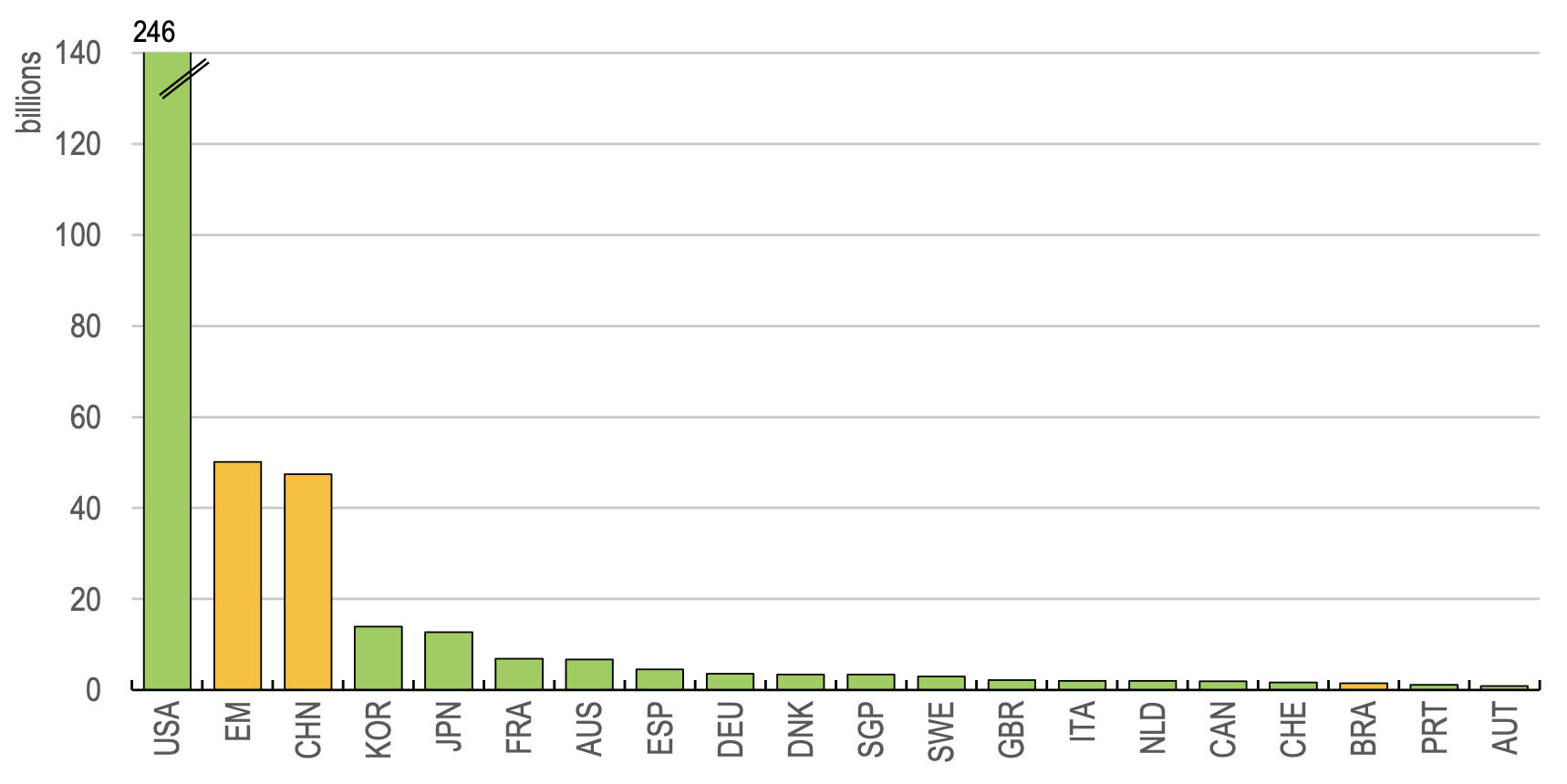

The distribution of investment by ‘green’ funds, as defined above, is heavily skewed towards the US, which represents almost 70% of green investment destinations in our sample. The People’s Republic of China is by far the next largest investment destination and represents the lion’s share of green investments in EMs. Brazil comes a distant second, but still much larger than the next EMs on the list – Chinese Taipei, South Africa, Mexico, India, Thailand and Poland. Overall, EMs represent only 13.6% of total green investment by ‘green’ funds in our sample, and less than 1% excluding China (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Market value of specialised green funds’ positions in green companies, 2023Q1 (billion US dollars)

Note: Sample of 14,000 “green” securities held by 1600 “green” funds. Green companies are defined as companies with revenues in key sectors involved in climate transition, including renewable energy, transport, buildings, and energy efficiency. Source: Morningstar, OECD calculations.

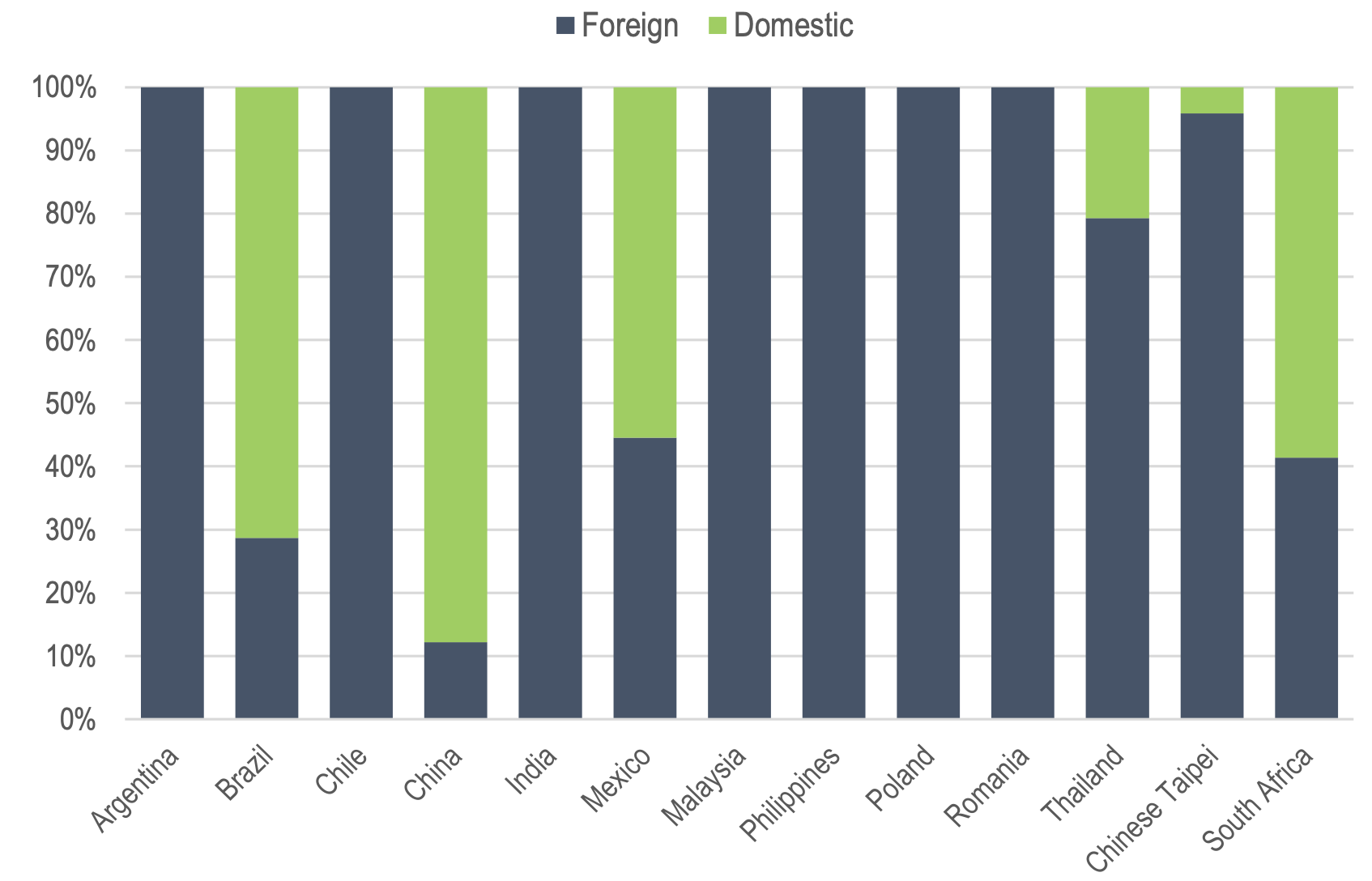

There is important heterogeneity in the origins of green investments: in Argentina, Chile, India, Malaysia, Philippines, Poland and Romania, investments tracked are entirely from foreign green funds; in China, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa and, to a lower extent, Thailand, the majority of green investments come from domestic green funds with domestic allocation mandates (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Origin of green funds investing in EM green assets (%)

Source: Morningstar, OECD calculations

Note: Sample of 1,600 ‘green’ funds, defined as funds with more than 25% of the eligible portfolio involved in carbon solutions.

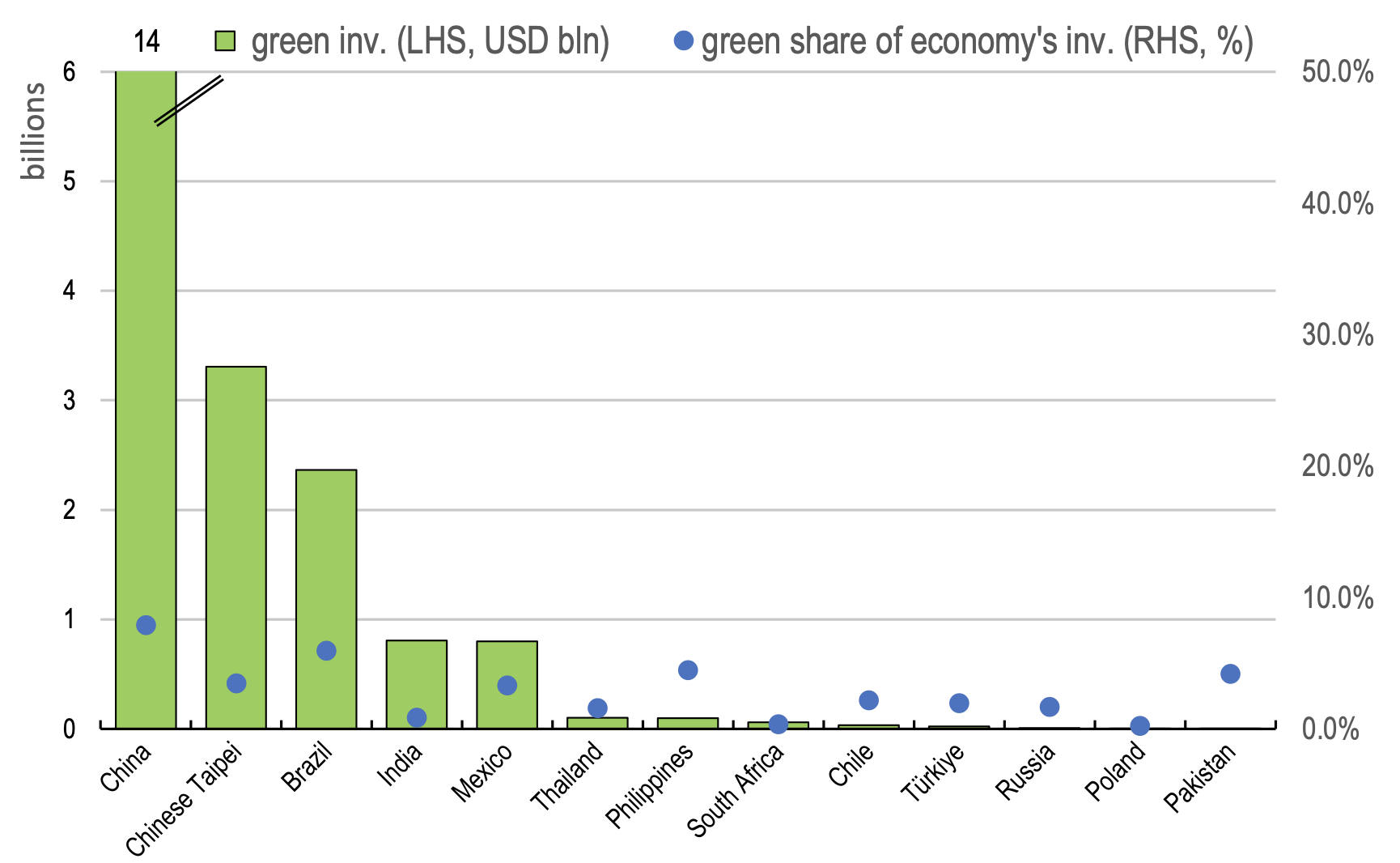

Global EM equity funds also invest little in green companies

While the previous section analysed the EM allocation of investment funds specialised in green companies, an analysis of the green allocation of investment funds specialised in EMs, specifically global EM equity funds, also highlights that green companies represent only a small share of invested stocks (Figure 3). This share amounts to an average of 9.6% of a fund’s portfolio, with China remaining the main investment destination.

Figure 3 Market value of global EM equity funds’ positions in green companies in EMs, 2023Q1 (billion US dollars)

Note: Sample of 714 global EM equity funds. LHS represents absolute value of green investments in each destination. RHS represents share of green investments (% total investments by global EM funds in this market).

Source: Morningstar, OECD calculations.

Overall, the green investments that EMs do receive appear to primarily go to countries with deeper financial markets and large domestic investor bases, and those with key market players in renewable energy value chains. For example, China attracts remarkable investments in sub-sectors such as solar photovoltaic panels and electrical vehicle batteries, where it has a dominant role in the global manufacturing value chain (OECD 2023b). In Brazil, they appear to be mainly energy utility companies in generation and distribution.

Hurdles to the allocation of green investment in EMs

Multiple factors act as barriers to the allocation of green investment in Ems. These range from potentially inappropriate interpretation regarding climate impact of investments based on current ESG ratings and labels, to more structural issues related to EM risk/return profiles and the current functioning of global capital markets, as well as inadequate supply of ‘ESG-rated green investable assets in EMs.

In particular, the current structure of global capital markets works against a greater allocation of fund investments in EM companies, let alone green ones. Institutional investors and indices are biased towards large listed companies, which leaves smaller and growth firms in EMs off the radar of institutional investors. Index and rating driven investment – which represent an increasing share of global AUM – favours larger companies, higher credit ratings and higher free float levels (De La Cruz et al. 2019). EM companies are seldom included in indices and EM corporate bonds have lower credit ratings.

Conclusions: What’s next?

Firstly, more detailed analysis would be needed to understand why certain EMs and sectors receive more green investments than others, with a focus on comparing EMs and AEs to draw valuable lessons.

Besides, much more work would be needed to assess the implications for capital flow volatility and reallocation resulting from climate transition risks, and notably divestment from ‘brown’ sectors (Mojon et al. 2021, Loyson et al. 2023).

Further research should also explore how capital markets can efficiently allocate financing to innovative growth companies and EMs, considering existing market constraints.

Finally, ESG ratings should be given more careful interpretation with a need to enhance the quality of data, disclosure, and transparency related to rating methodologies, and alternative rating systems focused on climate impact should be developed.

In terms of policies, our report highlights that lifting one or some of the bottlenecks to green investment in EMs is unlikely to lead to significantly stronger flows. What is needed is a comprehensive approach to the issue, taking into account countries’ differences in capital market structures.

References

Bolton, P, A Kleinnijenhuis, T Adrian (2022), “COP27: Climate finance for developing countries is not just equitable, it is self-interest”, VoxEU.org, 11 November.

Couto, L.(2023), “The role of central banks, financial regulators and sectoral coalitions”, Chatham House.

De La Cruz, A, A Medina and Y Tang (2019), “Owners of the World’s Listed Companies”, OECD Capital Market Series.

IEA - International Energy Agency (2021), Financing clean energy transitions in emerging and developing economies.

Knutsson, P and P Flores (2022), “Trends, Investor types, and drivers of renewable energy FDI”, OECD Working Papers on International Investment 2022/02.

Loyson, P, R Luijendijk and S van Wijnbergen (2023), “Pricing climate transition risk in Europe’s equity market”, VoxEU.org, 30 August.

Mojon, B, C Monnet, E Jondeau (2021), “Brown assets might be the next subprime”, VoxEU.org, 16 April.

OECD (2023a), Towards Orderly Green Transition: Investment Requirements and Managing Risks to Capital Flows, OECD Report to the G20 Finance.

OECD (2023b), Strengthening clean energy supply chains for decarbonisation and economic security.

OECD (2022), “ESG ratings and climate transition: An assessment of the alignment of E pillar scores and metrics”, OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers 06.

Pastor, L, R Stambaugh and L Taylor (2023), “Green tilts”, VoxEU.org, 13 August.

Songwe, V, N Stern and A Bhattacharya (2022), Finance for climate action: Scaling up investment for climate and development, Report of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance.