The current productivity slowdown in advanced economies has triggered a lively debate about its causes and remedies (Gordon 2016, Gordon 2018, Fernald 2018, Mokyr 2018). The long phase of post-WWII robust growth, which led to unprecedented progress in living standards, recently gave way to a new phase of deceleration in output per hour worked and sluggish total factor productivity (TFP) growth. In a recent paper (Prados de La Escosura and Rosés 2020), we take a long-run perspective to study the drivers of productivity expansion and stagnation over the long term in order to shed light on the causes of today’s poor productivity performance. We focus our analysis on productivity growth in Spain over the last 170 years.

The big picture: The Spanish economy in the long run

Spain is an interesting case to study since it was a laggard country before the 1950s that was able to catch up with the most advanced economies during the golden era of European growth. However, for the last 170 years, the country has always adopted foreign technologies – sometimes with a substantial delay – but it was never among the technological leaders.

A closer look reveals several phases with different growth patterns in Spain’s economic development. Between the mid-nineteenth century and the Golden Age (1954-75), GDP grew at a yearly average rate of 1.5%, to which output per hour worked contributed about three-fifths. The Golden Age then witnessed an impressive GDP growth acceleration, almost exclusively attributable to labour productivity (5.8% of 6.2% GDP growth).

A new pattern emerged after 1975 with the Spanish economy unable to combine employment creation and labour productivity growth, resulting in moderate GDP per capita growth (1.5%) during this transition-to-democracy period (1975-1985). However, labour productivity growth still more than offset the sharp decline in hours worked per person caused by the closure of inefficient industries which had previously been sheltered from competition. With Spain’s EU accession in 1985, GDP growth accelerated again (3.7% yearly) with nearly half of it resulting from an increase in hours worked per head, while labour productivity only contributed one-third. The Financial Crisis years of 2008-13 saw a pace of employment destruction comparable to the one experienced during the transition-to-democracy phase but without the strong labour productivity response. In the recovery years after the financial crisis (2014-19), GDP growth stemmed mainly from the increase in hours worked per person (2.0% out of 2.6% GDP growth rate).

Accounting for labour productivity growth

Over the whole period from 1850-2019, capital deepening contributed to about half of the growth in labour productivity and efficiency gains contributed about one-third, with the remainder attributable to labour quality (Figure 1). However, the overall yearly rate of TFP growth is quite modest (0.6 % per year). The major spikes in TFP growth rates generally coincide with the adoption of new general-purpose technologies (GPTs), substantial structural change and labour reallocation towards the most advanced industries.

Figure 1 Labour productivity growth and its sources, 1850-2019* (%)

Note: * TFP derived with education-based labour quality

A closer look at the evolution of TFP also allows us to distinguish several different phases, with cycles of TFP expansions followed by periods of sluggish or negative TFP growth rates. TFP contributed to about half of the growth in labour productivity, but with quite modest growth rates from 1850 to 1892. Those years were marked by openness and modernisation, including the introduction of railways and other foreign industrial technologies. This cycle was followed by a period of slower productivity growth that lasted until the end of WWI, with negative TFP rates. The 1920s experienced robust labour productivity growth to which TFP contributed between half to two-thirds and TFP growth rates were over 2% per year. The manufacturing sector expanded vigorously during this cycle thanks to the adoption of electricity and other imported innovations. This expansion came to an abrupt halt with the great depression and the Spanish Civil War. The first years of Franco’s dictatorship saw a slow come back to the previous levels but the recuperation took longer than in other European countries. Up until this point, human capital had contributed only marginally to labour productivity gains.

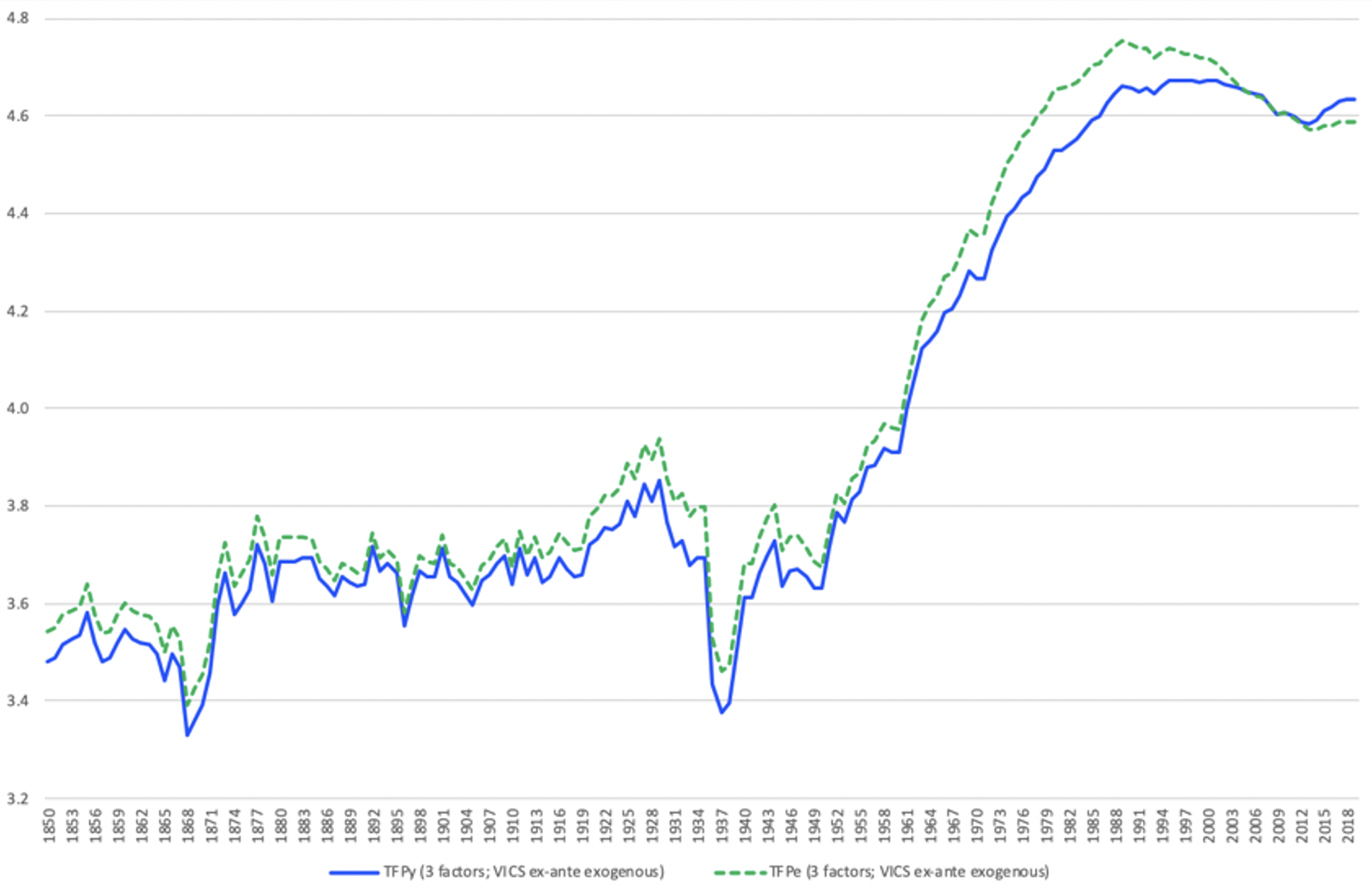

Figure 2 Total factor productivity: Estimated with income- and education-based labour quality (2010=100) (logs)

The situation changed dramatically during the Golden Era (1954-85), in which output per hour worked grew exceptionally fast (5.7%). Efficiency gains contributed to nearly half of its growth and physical capital accounted for another two-fifths (Figure 2). TFP growth rates were exceptional, exceeding 3% per year. The period saw the Spanish manufacturing sector adopting mass production as well as a labour reallocation from agriculture to industry and services. Between Spain’s accession to the EU (1985) and the eve of the Global Crisis (2007), labour productivity growth actually shrank with capital deepening contributing four-fifths. During the crisis years (2008-2013), capital drove the mild acceleration in labour productivity growth, while TFP growth was negative. In the post-2013 recovery, TFP has led a meagre labour productivity growth as the contribution of capital turned negative.

Explaining the productivity slowdown

Why did TFP growth stall after 1985? A potential explanation might be a benign convergence hypothesis. As Spain approached the technological frontier, achieving further efficiency gains became more difficult. Moreover, the once-and -for-all shift of resources from sectors of low, or slow-growing productivity (i.e. agriculture) to those of high, or fast-growing productivity (i.e. manufacturing) had already taken place. Hence, Spain’s potential for catching up was exhausted and TFP growth slowed down adjusting its pace to advanced economies. However, this hypothesis must be rejected as all OECD countries that had higher initial levels of output per hour worked than Spain in 1990, exhibit faster TFP growth between 1990-2019 (Conference Board 2020).

Alternative explanations of the TFP slowdown are for example that as resources were reallocated towards sectors attracting less innovation (from traded to non-traded sectors, i.e. low skill services and construction), aggregate efficiency declined. Such reallocation happened for instance via investments in residential structures, stimulated by favourable relative prices and subsidies, as well as low investment-specific technical change (ISTC) (Díaz and Franjo 2016) and low investment in intangibles (Pérez and Benages 2017). Moreover, low skills have limited scope to exploit new technologies (Cuadrado et al. 2020). The increase of structures’ share in net capital stock and its substantial contribution to the total value of capital services in the early 21st century, together with the deceleration of capital ‘quality’ since 1990, support these assertions (Prados de la Escosura 2020).

But what are its ultimate determinants? Allocative inefficiency across firms, rather than across sectors, results from government regulation (García-Santana et al. 2019). Regulatory restrictions to competition in product and factor markets account for firms’ low expenditure on research and development and low investment in intangible capital (Alonso-Borrego 2010). Specifically, retail trade regulation, the costs of firm creation, lack of flexibility in the labour market, bankruptcy legislation and judicial procedures all reduce competition (Mora-Sanguinetti and Fuentes 2012).

It can then be hypothesised that obstacles to competition in product and factor markets, subsidies, and cronyism led to capital misallocation, which together with low investment on intangibles and ISTC negatively affects capital deepening and TFP growth. This is consistent with the fact that expanding sectors creating more jobs (construction and services) have lower labour productivity relative to industry jobs. They hence experienced slower output per hour growth (Prados de la Escosura 2017), and were consequently less successful in attracting investment and technological innovation.

References

Alonso Borrego, C (2010), “Firm behavior, Market Deregulation and Productivity in Spain”, Banco de España Documento de Trabajo 1035.

Conference Board (2020), Total Economy Database.

Cuadrado, P, E Moral-Benito and I Solera (2020), “Sectoral Anatomy of the Spanish Productivity Puzzle”, Banco de España Documentos Ocasionales 2006.

Díaz, A and L Franjo (2016), “Capital Goods, Measured TFP and Growth: The Case of Spain”, European Economic Review 83(1): 19-39.

Fernald, J (2018), “Is Slow Productivity and Output Growth in Advanced Economies the New Normal?”, International Productivity Monitor 35: 138-148.

García-Santana, M, E Moral-Benito, J Pijoan-Mas and R Ramos (2020), “Growing Like Spain: 1995-2007”, International Economic Review 61(1): 383-416.

Gordon, R J (2016), The Rise and Fall of American Growth. The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Gordon, R J (2018), “Declining American Economic Growth despite Ongoing Innovation”, Explorations in Economic History 69: 1–12.

Mokyr, J (2018), “The Past and the Future of Innovation: Some Lessons from Economic History”, Explorations in Economic History 69: 13–26.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J S and A Fuentes (2012), “An analysis of productivity performance in Spain before and during the crisis: Exploring the role of institutions”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper 973.

Pérez, F and E Benages (2017), “The Role of Capital Accumulation in the Evolution of Total Factor Productivity in Spain”, International Productivity Monitor 33: 24-50.

Prados de la Escosura, L (2017), Spanish Economic Growth, 1850-2015, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Prados de la Escosura, L (2017), Historical GDP estimates: Updated data.

Prados de la Escosura, L (2020), “Capital in Spain, 1850-2019”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15364.

Prados de la Escosura, L and J R Rosés (2020), “Accounting for Growth in Spain, 1850-2019”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15380.