Inflation expectations play a key role in the monetary transmission mechanism via the real interest rate channel as well as in wage and price setting processes. Therefore, understanding the nature of economic agents’ inflation expectations and how they are formed is crucial for monetary policymakers.

In a recent paper (Reiche and Meyler 2022), we analyse consumers’ one-year ahead inflation expectations using data available from the European Commission Consumer Survey (ECCS) through the lens of uncertainty and address some of the more puzzling stylised facts of these inflation expectations, namely that: (a) the average expectation has tended to be systematically above, although co-moving with, actual inflation, (b) there is an apparent negative correlation between inflation expectations and economic sentiment, and (c) there is substantial heterogeneity both across countries and across individuals in terms of the levels of inflation expectations. It should be borne in mind that consumers’ one-year ahead inflation expectations may be more volatile and responsive to actual inflation developments than their more medium or longer-term expectations.

While the link of consumers’ inflation expectations with sociodemographic characteristics and economic sentiment is a well-known feature, the uncertainty framework offers explanations for both the bias in quantitative inflation expectations vis-à-vis actual inflation and their negative relationship with economic sentiment. Previous literature shows that consumers are likely to have higher inflation perceptions and expectations if they are younger, female, have lower levels of formal education, and belong to lower income groups.

Furthermore, consumers that report being in a better financial situation and who have positive expectations about the economy as a whole are associated with lower inflation expectations; this also holds when controlling for sociodemographic factors.

The uncertainty framework helps explain some of the bias as agents who are more uncertain typically report their inflation expectations using round figures (in multiples of five). Furthermore, those who have a negative attitude about the economy as a whole also tend to be more uncertain about the inflation outlook and to report higher inflation expectations. This explains why reported inflation expectations might increase in periods of economic uncertainty.

Looking at consumers’ inflation expectations through the lens of uncertainty

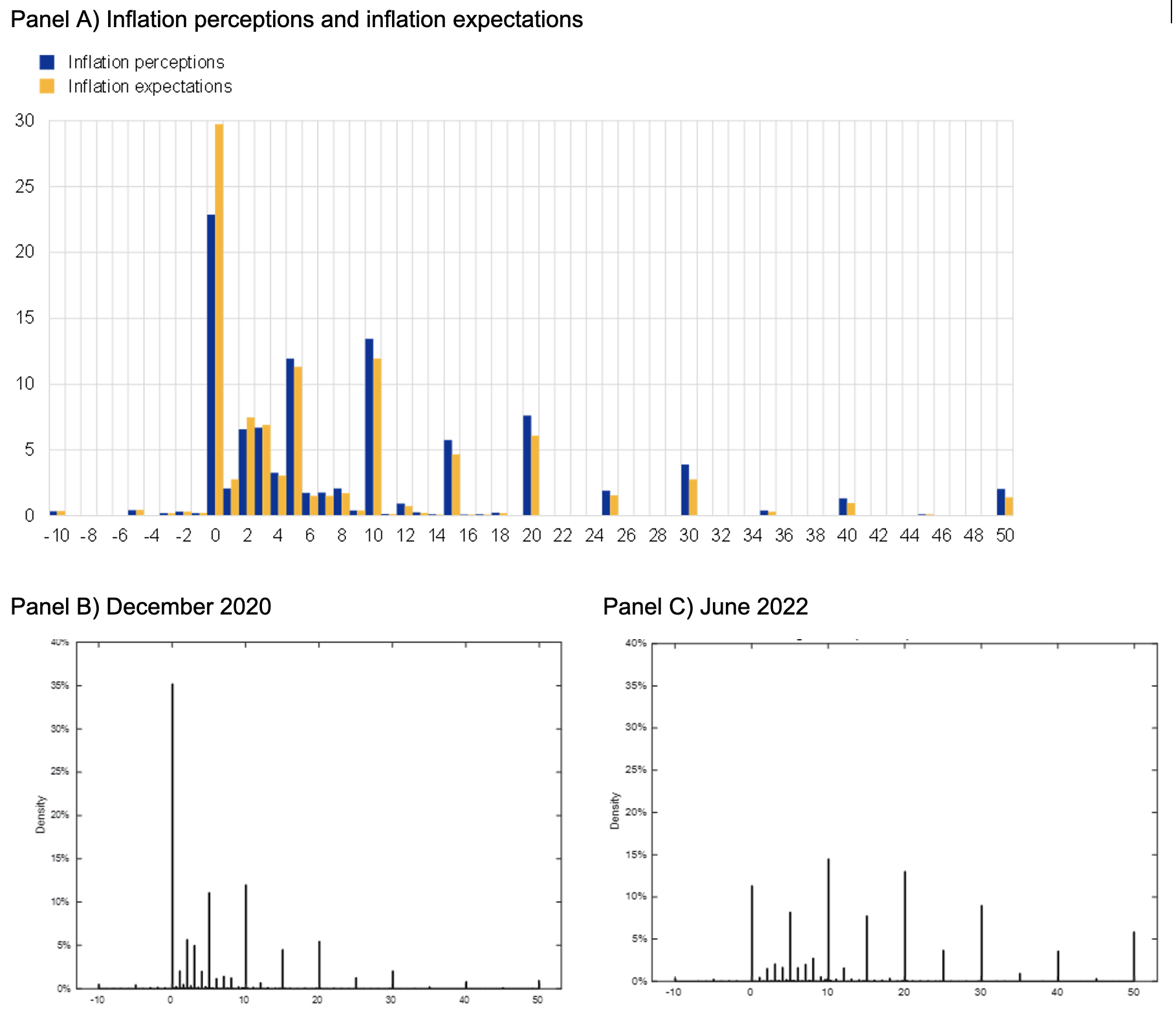

The high frequency of rounding observed in consumers’ quantitative inflation expectations points to uncertainty in reported inflation expectations. A considerable share of euro area consumers reports their quantitative expectations (and perceptions) using round numbers (most notably multiples of five and ten), while other consumers report to single digits or even to decimals. Panel A of Figure 1 shows noticeable peaks at 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%, with a smaller distribution of respondents reporting to single digits. The modal responses of this latter group are around 2%-3% and thus not as biased as the aggregate numbers.

According to communications and linguistics theory, round numbers – typically multiples of five or of ten, depending on the context – are frequently used to convey that a quantitative expression should be interpreted as imprecise. We use the ‘round numbers suggest round interpretations’ principle to identify the existence of an uncertainty channel which may influence reported inflation expectations.

Panels B and C of Figure 1 illustrate a considerable shift in the histogram of one-year ahead inflation expectations between December 2020 (when euro area Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) inflation was -0.3%) and June 2022 (when euro area HICP inflation was 8.6%), suggesting that both certain and uncertain consumers’ one-year ahead inflation expectations co-move with actual inflation (although the former to a much lesser degree).

Figure 1 Histogram of inflation perceptions and expectations (y-axis: frequency of response as percentages)

Sources: European Commission DG-ECFIN and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Histogram constructed at integer level.

What determines whether individuals are (un)certain?

Whether a consumer is certain about price developments can depend on sociodemographic characteristics and/or economic sentiment. To analyse this, we explain rounding behaviour using a range of sociodemographic and economic sentiment variables. This can be used to estimate an individual ‘probability that a consumer is certain’ about inflation.

The sociodemographic variables include characteristics, such as age, level of formal education, gender, and income quartile. In addition, sentiment indicators are used, which take the form of expressed economic opinions on the expected personal financial and general economic situation, a qualitative inflation assessment about inflation in the next 12 months, and opinions on unemployment development, as well as on the timing of purchases and savings.

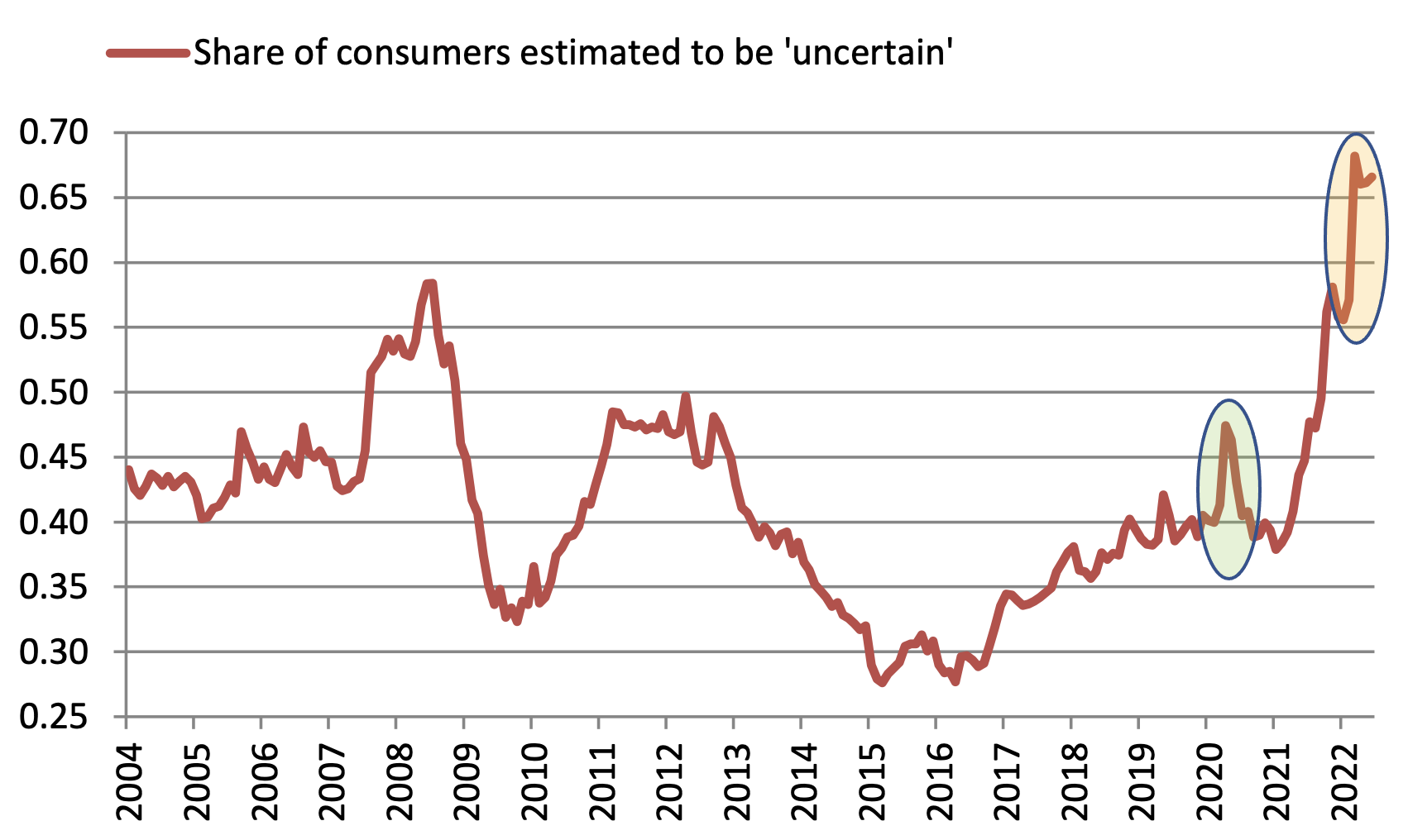

On average, and other things being equal, a higher income and higher level of formal education contribute positively to an individual’s estimated probability of being certain. Certainty increases further with age and if respondents are male. At the same time, respondents tend to be less certain if they are more negative about their personal finances, the general economic situation including unemployment and their ability to purchase and save. In addition, it is found that a higher level of actual inflation increases our measure of uncertainty). These patterns hold robustly across most time periods and euro area countries in our sample. Figure 2 shows an index of inflation expectations uncertainty over time, where uncertainty is represented by the share of respondents reporting inflation expectations as multiples of five and/or ten (excluding those reporting zero). Noticeable peaks are visible at the time of the global crisis in 2008, to a lesser extent around 2011-2013 during period of euro area sovereign debt tensions, after the emergence of the coronavirus pandemic,

and again towards the end of 2021. Indeed, in April 2020 when the first strong impact from the pandemic affected Europe, there was a decline in the share of consumers reporting inflation expectations of zero or digits from 1% to 4%, with noticeable increases in those reporting multiples of five (in particular 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30%). Most recently, there was a further noticeable surge in uncertainty, as measured by consumers’ rounding behaviour, in the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Figure 2 Inflation uncertainty index (y-axis: percent)

Sources: European Commission DG-ECFIN and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Series shows percentage of respondents reporting inflation expectations in multiples of five or ten (excluding those reporting zero). The measure rises with rising actual inflation, as more respondents report ‘extreme’ inflation expectations such as 20%, 30%, 40%, or even 50%. The highlighted periods denote April 2020 (when first pandemic lockdowns started) and March 2022 (after Russian invasion of Ukraine).

Does this (un)certainty framework help explain and foster greater understanding of inflation expectations?

Overall, our model of inflation expectations helps understand the data better. First, we estimate the linear effects of sociodemographic and economic sentiment variables on quantitative inflation expectations.

Moreover, to control for potentially different macroeconomic environments, actual inflation (HICP), inflation forecasts by Consensus Economics, and GDP growth by country and time are incorporated. The (un)certainty framework is then used to split the sample. This makes it possible to show whether the effect of these sociodemographic and economic opinion variables differs between more and less certain consumers.

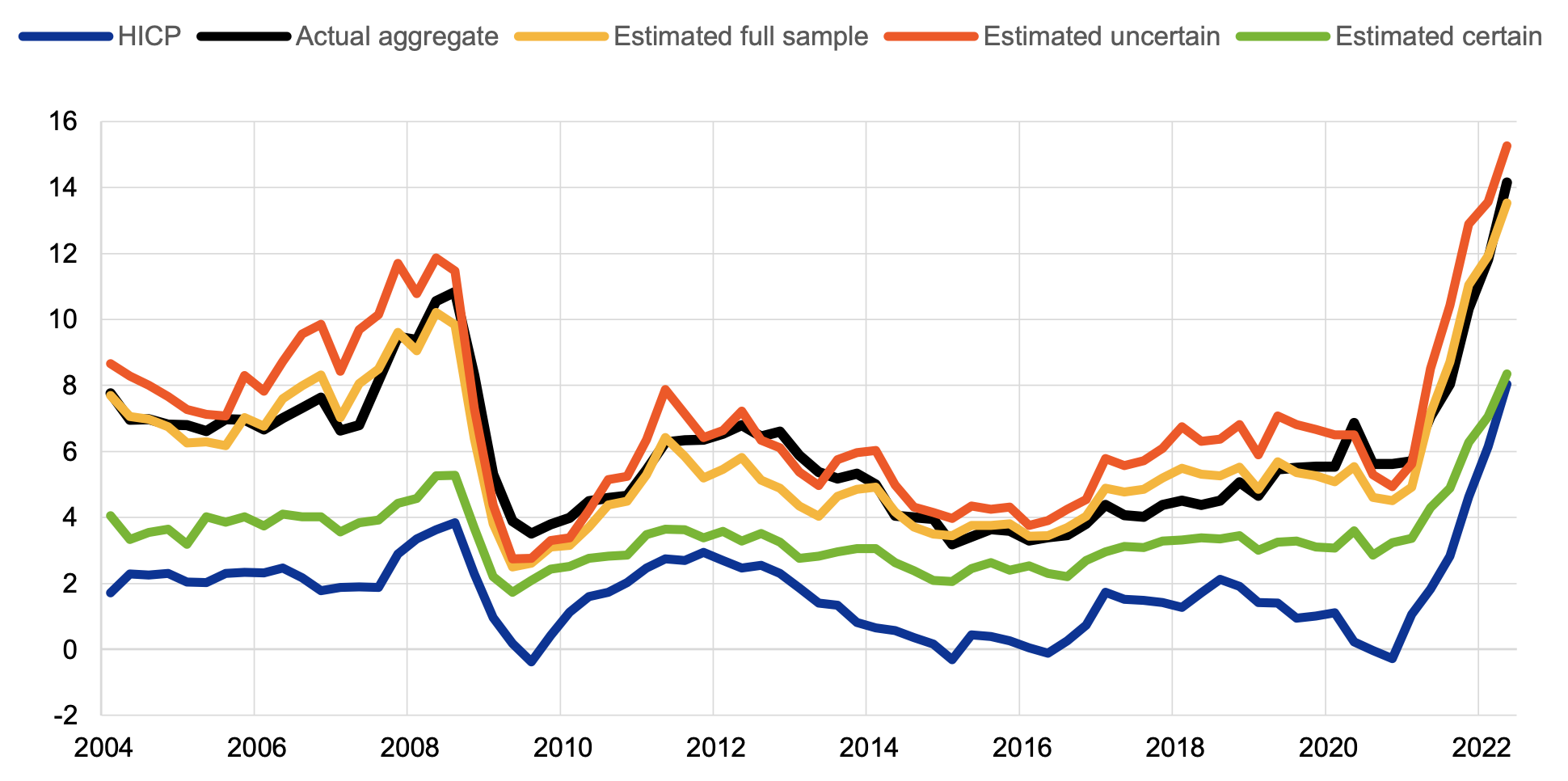

Dividing the sample into the ‘certain’ and ‘uncertain’ groups explains a large part of the so-called inflation expectation conundrum, i.e. the overestimation of inflation in consumer surveys.

Applying the above model shows that sociodemographic and sentiment variables have a smaller impact on the inflation expectations of the ‘certain’ group. The difference in inflation expectations between the ‘certain’ and ‘uncertain’ groups is visualised in Figure 3 and contrasted with aggregate estimates. It suggests that the differential in inflation estimates observed between socioeconomic groups and respondents of diverging economic assessments can at least in part be explained by the different levels of certainty these groups of respondents have about future inflation. These results also hold in a model version that controls for perceptions, given their strong link with expectations. However, it should be noted that even consumers who are certain, i.e. do not round their inflation estimates, overestimate inflation. Therefore, the certainty channel should not be considered in isolation from other hypothesised reasons, including psychological aspects of loss aversion, seasonality, and the idea that consumers might have in mind different and very heterogeneous baskets (including house prices, for instance) when estimating inflation.

Figure 3 Estimated inflation expectations: Fitted versus survey results (y-axis: percentages)

Sources: European Commission DG-ECFIN, Eurostat, and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: This chart displays the estimated one-year inflation expectation calculated for a mean individual (i.e. an individual with mean characteristics in each category) in each country. HICP country weights are then used to aggregate across the euro area. The latest observation is Q2 2022.

We have shown that inflation uncertainty is an important channel that helps shed light on some of the more puzzling aspects of reported quantitative inflation expectations.

This framework may be more pertinent in the current environment of heightened geopolitical tensions and energy prices which are volatile and elevated. However, there remain aspects of consumers’ inflation expectations that cannot be addressed using the data considered in our paper. For instance, as we do not observe the same individual over time, it is challenging to understand how expectations are formed and the extent of their economic impact. In the future, the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey (CES), which was launched as a pilot in 2020 and has a genuine panel structure, could offer a more in-depth view of consumer expectations over time, their formation, and how consumers understand and react to monetary policy.

Authors’ Note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB or the European Commission. The authors are grateful to Carola Binder for sharing her Matlab code used for the Binder (2017) paper. We also acknowledge useful comments and suggestions from members of the Eurosystem Expert Group on Inflation Expectations as well as participants at an internal ECB presentation. All remaining errors are under the full responsibility of the authors.

References

Abe, N and Y Ueno (2016), “The mechanism of inflation expectation formation among consumers”, RCESR Discussion Paper Series, No DP16-1, Hitotsubashi University, March.

Abildgren, K and A Kuchler (2021), “Revisiting the inflation perception conundrum”, Journal of Macroeconomics 67.

Afunts, G, M Cato, S Helmschrott and T Schmidt (2022), “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to higher inflation expectations of individuals in Germany”, VoxEU.org, 20 April.

Arioli, R, C Bates, H Dieden, I Duca, R Friz, C Gayer, G Kenny, A Meyler and I Pavlova (2016), “EU Consumers’ Quantitative Inflation Perceptions and Expectations: An Evaluation”, European Economy Discussion Paper No. 38, European Commission, November.

Binder, C (2017), “Measuring uncertainty based on rounding: New method and application to inflation expectations”, Journal of Monetary Economics 90(C): 1-12.

Bryan, M and G Venkatu (2001), “The Demographics of Inflation Opinion Surveys”, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary, October.

D’Acunto, F, U Malmendier and M Weber (2022), “Learning about inflation expectations from the data”, VoxEU.org, 7 May.

Del Giovane, P, S Fabiani and R Sabbatini (2008), “What’s behind ‘inflation perceptions’? A survey-based analysis of Italian consumers”, Working Paper No 655, Banca d’Italia, January.

Draghi, M (2015), “Introductory Statement, European Central Bank”, 22 October.

Ehrmann, M, D Pfajfar and D Santoro (2017), “Consumers’ Attitudes and Their Inflation Expectations”, International Journal of Central Banking 13(1): 225-259.

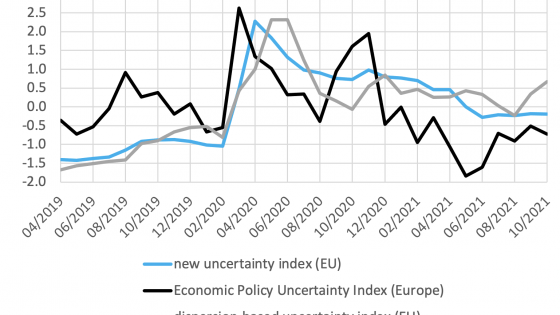

Gayer, C, A Reuter and F Morice (2021), “A new survey-based measure of economic uncertainty”, VoxEU.org, 29 November.

Hausman, J, J Abrevaya and F Scott-Morton (1998), “Misclassification of the dependent variable in a discrete response setting”, Journal of Econometrics 87(2): 239-269.

Jonung, L (1981), “Perceived and Expected Rates of Inflation in Sweden”, The American Economic Review 71(5): 961-968.

Kamdar, R (2019), “The inattentive consumer: Sentiment and Expectations”, Meeting Papers No 647, Society for Economic Dynamics: 109-132.

Krifka, M (2009), “Approximate Interpretations of Number Words: A Case for Strategic Communication”, in E Hinrichs and J Nerbonne (eds.), Theory and Evidence in Semantics, Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Reiche, L and A Meyler (2022), “Making Sense of Consumers’ Inflation Expectations: The role of uncertainty”, European Economy Discussion Paper No. 159, European Commission, February.

Yellen, J (2018), “Comments on Monetary Policy at the Effective Lower Bound”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 49(2): 573-579.