Editors' note: This column is part of the Vox debate on the economic consequences of war.

Consumers’ inflation expectations can play an important role in future inflation developments through the channel of perceived real interest rates. Shifts in consumers’ perceptions about the real rate of return can influence their consumption and saving decisions (Bachmann et al. 2015,D’Acunto et al. 2015). In addition, consumers consider future price increases when negotiating wage contracts (D’Acunto and Weber 2022, Coibion et al. 2020). Consequently, companies may raise prices in the face of higher wage pressure and costs. This is a very important mechanism that could affect the current level of inflation and make it more difficult for central banks to achieve their price stability goals (D’Acunto and Weber 2022). Therefore, understanding the alterations and potential de-anchoring instances is crucial for policymakers in the context of current events.

The outbreak of the war in Ukraine took the world by surprise. Although many had discussed potential scenarios for such an event, few anticipated its occurrence, or at least the exact day of its onset. This major unanticipated event played a decisive role in shaping consumer sentiment. To causally assess how the invasion of Ukraine from Russia affected consumers’ inflation expectations in Germany, we use an event study and complement it with a difference-in-difference analysis. We use the Bundesbank Online Panel of Households (BOP-HH) which includes more than 6,000 respondents surveyed in January, February, and March 2022. For the February wave, the interviews were carried out from 15 February to 1 March 2022. Information on the time of completion of the survey allows us to compare how short- and long-term inflation expectations differ between the group of consumers who responded to the questionnaire before the 24 February (control group) and those that answered after the invasion, in February and March 2022 (treatment group).

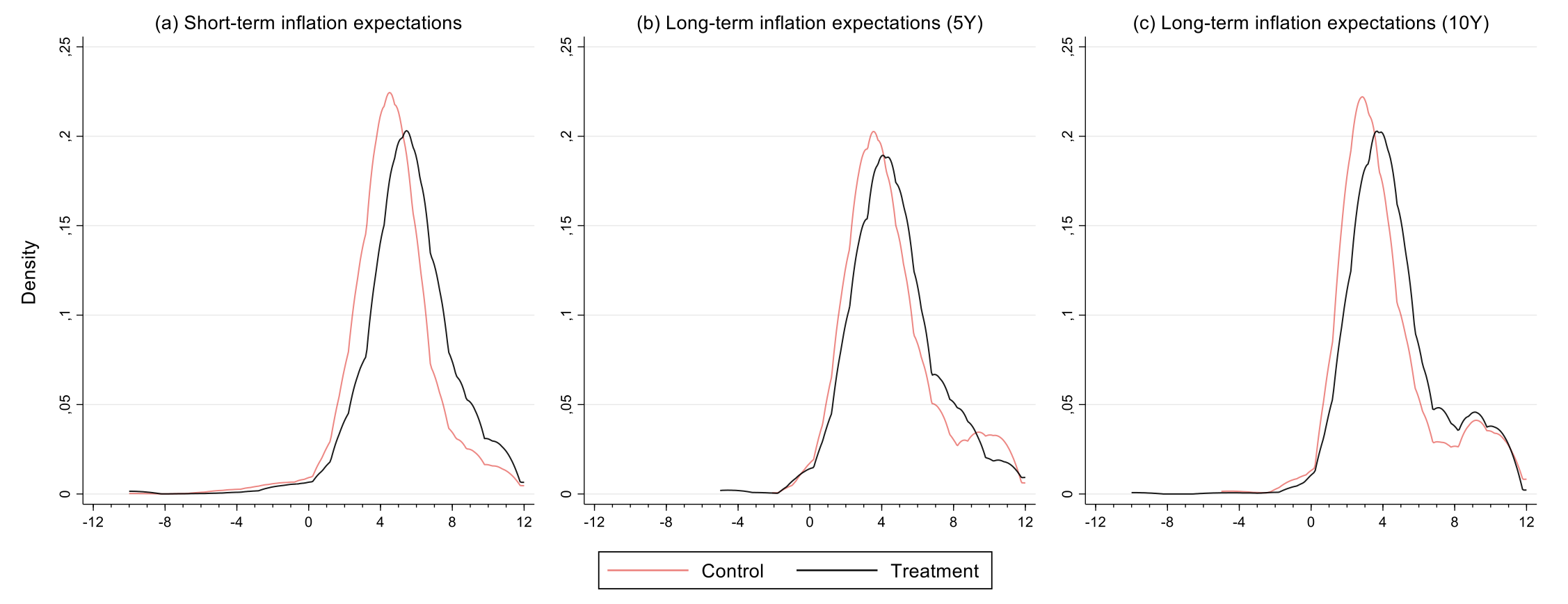

Figure 1 depicts the distribution of inflation expectations among households surveyed before the invasion began and among households surveyed after the invasion of Ukraine. In panel (a), we plot the distribution for the short-term inflation expectations (one-year ahead). The distribution for the consumers that filled the questionnaire after 24 February shifted considerably to the right. Consumers expected inflation to reach 4.7% over the next 12 months in data collected before the invasion. After the start of the war, the expected inflation rate increased to 5.6%, while the median increased from 5% (control group) to 5.5% (treatment group).

Long-term inflation expectations, for the next five and ten years on average, were also affected by the start of the war in Ukraine, but to a lesser extent than short-term. In panels (b) and (c), it is clear that the distribution of long-term expectations has also shifted to the right and that there is more mass at higher inflation rates. When asked about their expectations for the next five years, consumers who had not experienced the start of the war indicated an average (median) of 4.5% (4%). Those that responded after the war had begun, on the other hand, reported an average (median) of 4.8% (5%). A similar trend is observed for the very long-term inflation expectations in panel (c). Consumers in the control group had considerably lower expectations (mean: 4.2%) than the treatment group (mean: 4.6%).

Figure 1 Distribution of inflation expectations of consumers

Note: The figure plots the distribution of inflation expectations in the next twelve months (panel (a)), five years (panel (b)) and ten years (panel (c)). The control group is defined as respondents who filled in the questionnaire between 15 February and 23 February 2022. The treatment group is defined as respondents who filled in the questionnaire between 24 February and 1 March 2022 or between 15 March and 29 March 2022. Inflation expectations are measured as a point prediction and truncated between [-12%, 12%].

These shifts in both short-term and long-term inflation expectations are confirmed by using different regression models. While controlling for individual characteristics such as age, income, gender, and region of residence, we find that after the invasion of Ukraine, inflation expectations for the next 12 months increased by around 1.1%. The magnitude of this impact decreases as the forecast horizon expands.1 The start of the war in Ukraine leads to an increase in inflation expectations for the average over the next five and ten years, respectively, by around 0.4%.

We address two concerns related to our analysis. First, we account for existing pre-trend differences between the expectations of consumers in the control and treatment groups using the panel component of the survey.2 The results confirm our findings both on short-term and long-term inflation expectations of consumers, with a similar sign and magnitude. However, over the long term, the impact becomes statistically non-significant.3

The second concern is that there may have been an anticipation effect that preceded the event.4 For example, on 17 February 2022, President Biden stated a Russian invasion of Ukraine was very likely in the coming days. To investigate whether this announcement influenced inflation expectations, the sample is split into more than two periods: (1) pre-announcement (15 and 16 February); (2) day of the announcement (17 February); (3) post announcement, but before the invasion (18 to 23 February); and (4) the period after the invasion began (24 February and following days). We find no evidence of a significant impact of the announcement on average inflation expectations of individuals for the next twelve months.

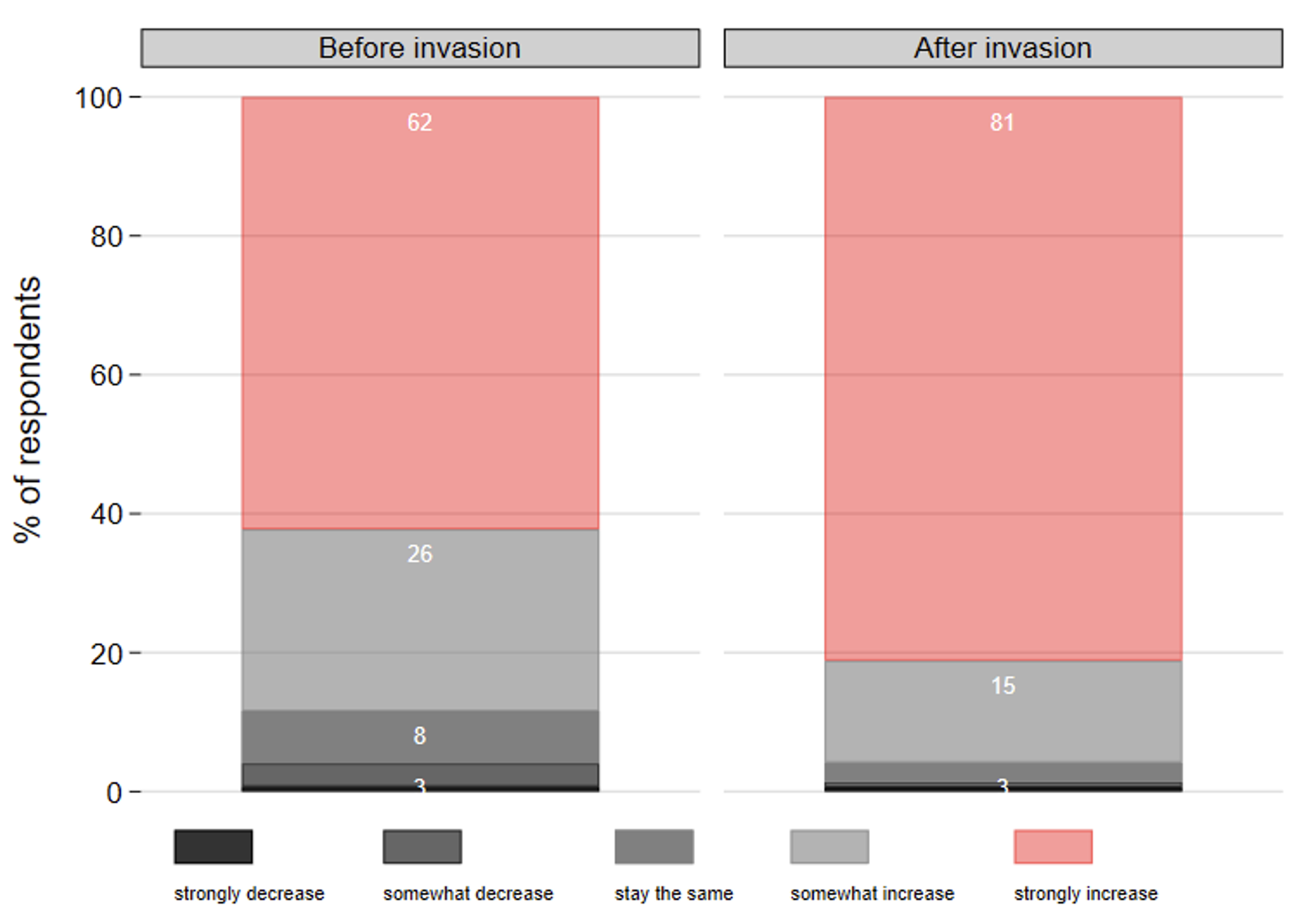

Related to the adjustment of individual expectations to the development of the general price level is the development of expectations for fuel prices (see Figure 2). The share of respondents expecting a “strong increase” in fuel prices over the next twelve months is at 81% after the invasion had begun. This is about 20 percentage points higher than the share in the pre-invasion period. This may be one of the main reasons behind the increased consumer inflation expectations shown above.

Figure 2 Expectations regarding fuel prices

Note: The figure depicts the results from the following question in the BOP-HH February wave: “What developments do you expect with regard to fuel prices over the next twelve months?” Each split in the bars represents the share of respondents answering in a specific category from: 1 decrease significantly, 2 decrease slightly, 3 stay roughly the same, 3 increase slightly, 4 increase significantly.

Conclusion

In this column, we analyse the immediate effect of the outbreak of the war on consumers’ inflation expectations. The results of a consumer expectations survey in Germany suggest that individuals reacted to Russia´s invasion of Ukraine by adjusting their short-term and long-term inflation expectations upwards, although the adjustment for the latter was considerably less. One major contributing factor to higher inflation expectations has been strong anticipation of further increases in energy prices because of the war.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are the authors’ personal opinions and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Deutsche Bundesbank or the Eurosystem.

References

Bachmann, R, T O Berg and E R Sims (2015), “Inflation expectations and readiness to spend: Cross-sectional evidence”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7(1): 1-35.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko and T Ropele (2020), “Inflation expectations and firm decisions: New causal evidence”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(1): 165-219.

D’Acunto, F and M Weber (2022), “Rising inflation is worrisome. But not for the reasons you think”, VoxEU.org, 4 January.

D’Acunto, F, D Hoang and M Weber (2015), “Inflation Expectations Spur Consumption”, VoxEU.org, 9 June.

Dräger, L, K Gründler and N Potrafke (2022), “Political Shocks and Inflation Expectations: Evidence from the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine”, CESifo Working Paper No. 9649.

Seiler, P (2022), “The Ukraine war has raised long-term inflation expectations”, VoxEU.org, 12 March.

Endnotes

1 Dräger et al. (2022) find similar results for short- and long-term inflation expectations of economics professors in Germany.

2 The survey has a rotating panel design. Therefore, we cannot track the full sample of respondents over all the month considered, but only a sub-sample.

3 It is very likely that the result are insignificant due to the very small number of observations we have for the sub-group of respondents that can be track back to January 2022. In BOP-HH, the question on short-term inflation expectations is asked every month to the full sample of respondents. However, for long-term inflation expectations the sample is split every wave in two groups, where one group is asked about their forecast in five years and the other for the forecast in ten years. Furthermore, in some waves it is asked only to new participants of the survey.

4 In the news, there was also a lot of coverage of the events preceding the invasion and there were many articles pointing to the direction of a full-scale invasion not happening (e.g. “Ukraine crisis: Five reasons why Putin might not invade - BBC News”.