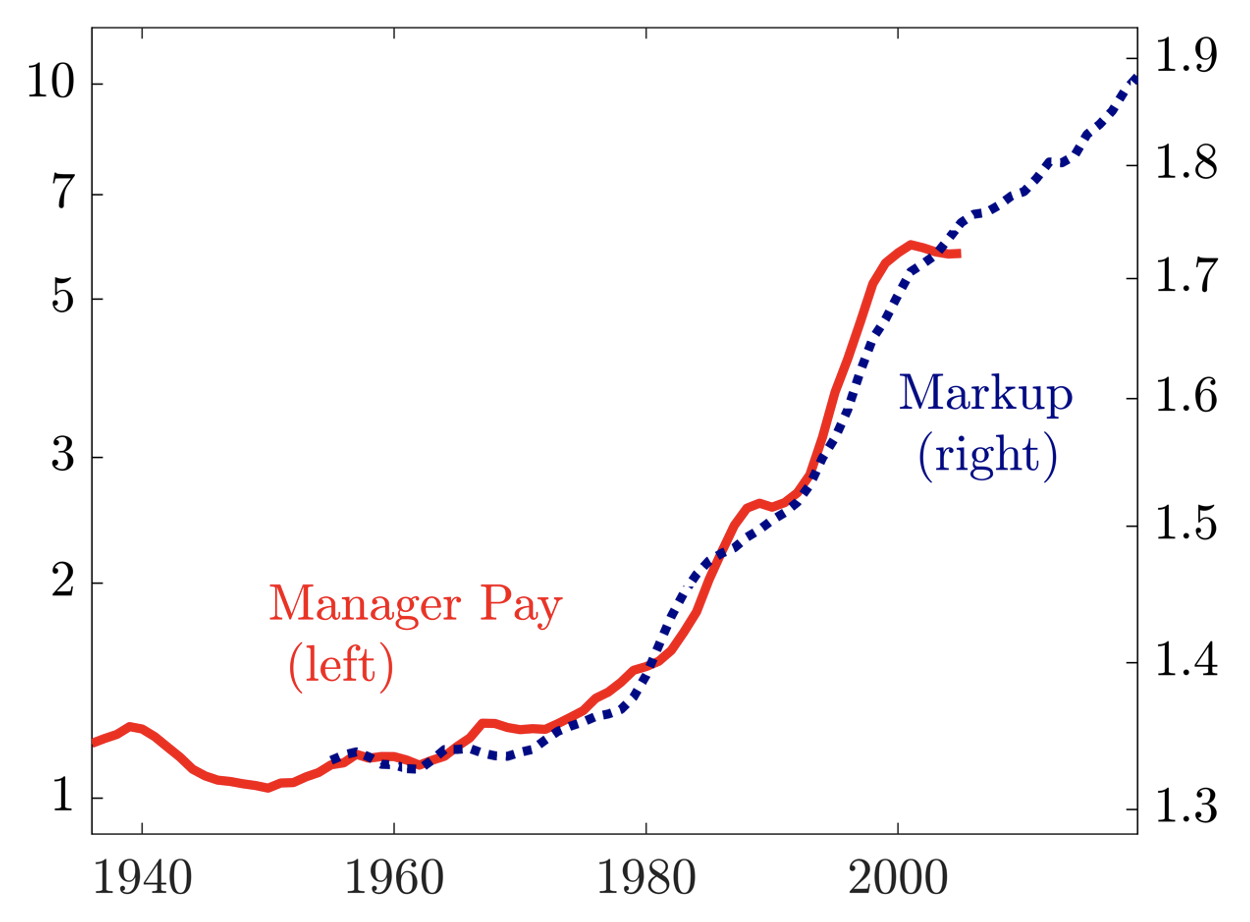

Inequality has increased substantially, mostly in the top 1% of the distribution (e.g. Piketty and Saez 2003) which comprises a lot of superstars. Since the 1980s, the pay of superstar workers has increased sharply. Whether they are professional athletes in the world’s best leagues of football, basketball or baseball, computer coders in the BigTech firms, or top managers in corporations – they have all experienced an enormous increase in pay. Figure 1 from Frydman and Saks (2010) shows the evolution of CEO pay since 1936, with a marked rise starting in the 1980s.

Figure 1 Average manager pay and markups

The pay of superstar workers is closely linked to the performance of the superstar firms that hire them. The question is, what makes these superstar firms so successful and why have the top-performing corporations become more successful over time? A key insight from the literature on executive compensation is that size matters (Gabaix and Landier 2008 and Terviö 2008). Over time, top corporations have become larger because new technologies allow them to produce higher volumes more efficiently due to economies of scale. The advent of the digital age with a central role of outsourcing and globalisation have been the key drivers of this rise in firm size.1

But these scale economies in the digital economy have at the same time increased monopoly power. Large productive firms also tend to be dominant firms in concentrated and, most often, global markets. Digital platforms for retail (Amazon), trading (eBay), and social interaction (Facebook), for example, have inherent network externalities that allow the incumbent to price goods and services substantially above cost. Not only does technology make firms large but it also allows them to make monopoly profits. And that affects manager pay. Figure 1 also shows the evolution of average markups, which show an increase since the 1980s that coincides with the rise of manager pay.

The job of the CEO is like a dam site in Akerlof’s (1981) model of the labour market. Just as only one dam can block the lake, only one person can perform the top job. These situations make performance to who is chosen particularly sensitive. The larger the potential lake, the bigger the dam you would like to build. In the market for managers, the dam is the manager’s ability. How well the manager performs depends not only on their abilities but also on the size of the firm. Gabaix and Landier (2008) and Terviö (2008) pointed out that as the size distribution of firms changes, so does the compensation of the manager, even if the manager’s ability does not change. As firms grow in size, the contribution of the manager to the value of a firm increases, and firms are willing to bid higher to poach the best manager. The rise in firm size is therefore behind the rise in manager pay.

But firms also exert monopoly power. And better managers are also better at running the firm in order to extract rents from customers. In our recent paper (Bao et al. 2022), we identify a mechanism that allows us to decompose the contribution of monopoly power to manager pay. Better managers make a firm more productive, and in a market with imperfect competition, more productive firms obtain higher profits by creating more market power. The effect from strategic pricing from imperfect competition increases all profits, but it does so more for the firms that are most productive to start with, before the manager’s contribution. The result is that firms with the most market power will bid the highest to get the best managers. The best manager increases profits more for high-market-power firms than for low-market-power firms.

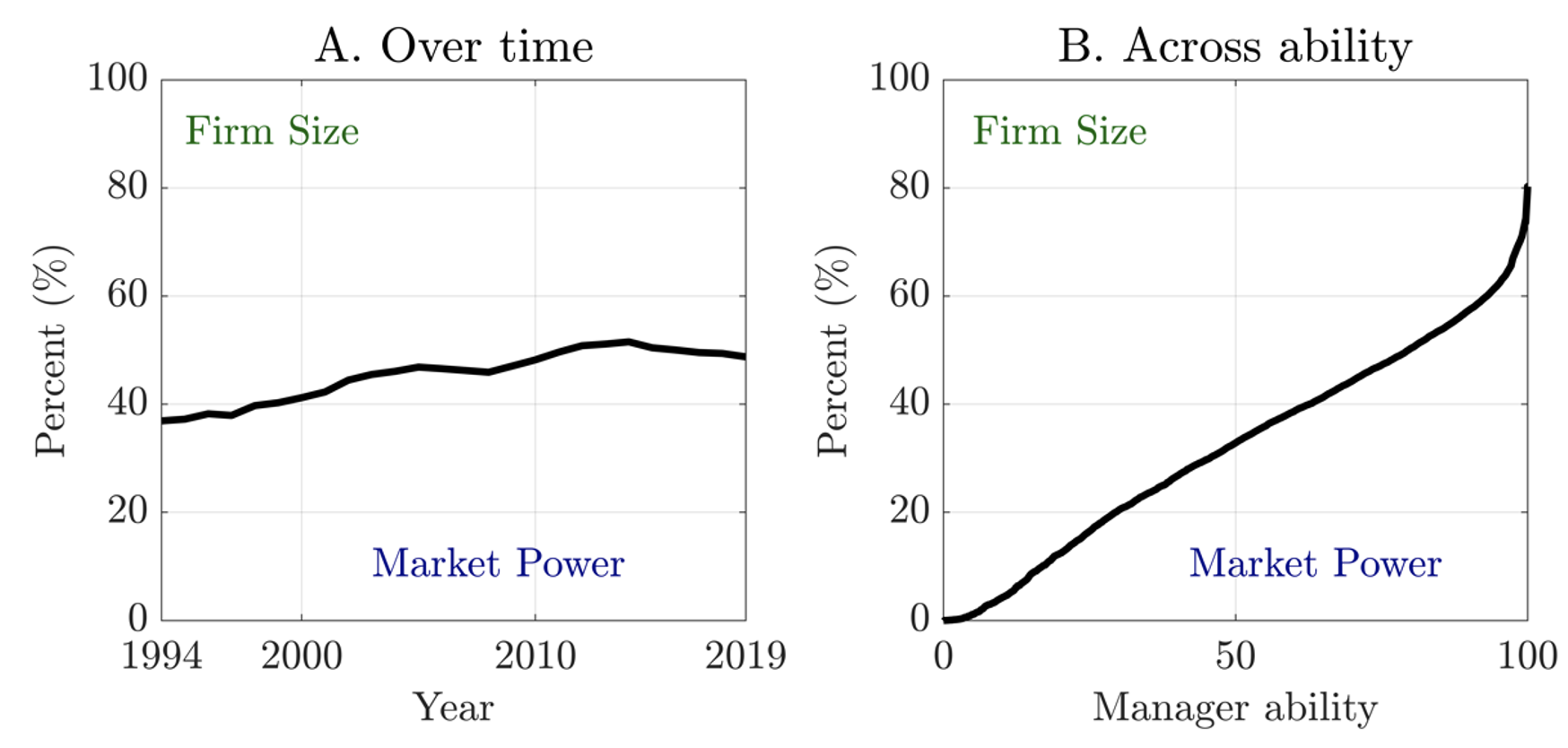

Our results are summarised in Figure 2. As can be seen in panel A, on average, 46% of manager pay is due to market power; the remainder is from the manager’s contribution to growing the firm. And this share has been growing over time, from 38% in 1994 to 49% in 2019. But most remarkable is the variation of the contribution of market power across manager ability, panel B. For the top managers, market power accounts for 80% of their pay in 2019!

Figure 2 Contribution of market power and firm size to manager pay (A) over time and (B) across managers of different abilities in 2019

Interestingly, firms hire top managers less because they are active in a productive and therefore large sector, and more because they are the top firm in the sector. Compare, for example, a sector with large firms such as retail with a small firm sector such as biotech. The top retail firm and the top biotech firm compete for the top managers, more than the top and bottom large retail firms compete for the top managers. This helps explain the quantitatively important role that market power plays in generating profits, and how the best managers contribute to those profits of the top firms within their market. Tim Cook is the superstar manager and Apple pays him nearly $100 million, not because he works for a large productive firm but because his firm is the dominant player in its market and hiring Tim Cook allows the firm to maximally exert its dominance. In fact, with 150,000 employees, Apple is much smaller than Walmart and Amazon in retail, Volkswagen and Toyota in car manufacturing, and FedEx and UPS in delivery services.

In sum, top managers are hired disproportionately by firms with market power, and they get rewarded for it – increasingly so. The main reason is that better managers help increase the rents from market power. Or to put it in the words of Warren Buffett in 2007:

I don’t want a business that’s easy for competitors. I want a business with a moat around it. ... Our managers of the businesses we run, I’ve got one message for them, which is to widen the moat.

References

Akerlof, G (1981), “Jobs as dam sites”, Review of Economic Studies 48(1): 37–49.

Amore, M, and S Schwenen (2020), “The value of luck in the labor market for CEOs”, VoxEU.org, 9 August.

Bao, R, J De Loecker and J Eeckhout (2022), “Are managers paid for market power?”, CEPR Dicussion Paper 17182.

Bell, B, and J Van Reenen (2016), “CEO pay and the rise of relative performance contracts: The role of governance”, VoxEU.org, 5 August.

Chaigneau, P, A Edmans and D Gottlieb (2021), “How CEO pay packages should be designed”, VoxEU.org, 4 May.

Frydman, C, and R Saks (2010), “Executive compensation: A new view from a long-term perspective, 1936–2005”, Review of Financial Studies 23: 2099–138.

Gabaix, X, and A Landier (2008), “Why has CEO pay increased so much?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 123: 49–100.

Terviö, M (2008): “The difference that CEOs make: An assignment model approach”, American Economic Review 98(3): 642–68.

Endnotes

1 Other determinants include luck; see for example Bertrand and Mullainathan (2001), Bell and Van Reenen (2016), and Amore and Schwenen (2020). And there is a large literature studying the design of CEO pay packages; see for example Chaigneau et al. (2021).