The Global Crisis exposed shortcomings in the assessment of cross-sector and cross-border linkages in the financial system. The interaction of banks and insurance corporations with shadow banking entities led to the amplification of risks and spillovers which were transmitted across sectors and national borders. Shadow banking entities can form part of complex financial intermediation chains which can also include banks, so mapping their linkages is important.

Since the crisis, there has been increased focus on monitoring the potential contagion channels between the banking system and particular shadow banking entities (e.g. ESRB 2016, Grillet-Aubert et al. 2016). The crisis revealed how such linkages can have negative externalities for the banking system and can act as an additional channel for the transmission of risk (Acharya et al. 2013, Covitz et al. 2013, BCBS 2015). Fischer (2015) points to the importance of mapping the linkages of shadow banking entities “which could guide regulatory efforts to collect data and set policies to limit instabilities associated with interconnectedness”. While the interconnectedness between banks and shadow banking entities is often cited as a key financial stability concern, EU bank-level and exposure-level evidence on these linkages has been lacking.

In a recent paper (Abad et al. 2017), we aim to fill this gap by mapping the exposures of EU banks to shadow banking entities using a unique dataset collected by the European Banking Authority (EBA) in March 2015 (see EBA 2015). We find that 60% of EU banks’ exposures are to shadow banking entities domiciled outside the EU, with approximately 27% of the total exposures to US-domiciled shadow banking entities. The final dataset we employ shows that EU banks had approximately 65% of the exposures to three types of shadow banking entities: securitisations (26%), investment funds other than money market funds (MMFs) (22%), and finance companies (18%). Furthermore, we show that individual banks have rather diversified exposures towards shadow banking entities. This diversification leads, however, to a high degree of overlap among banks’ exposures to different types of shadow banking entities.

What types of shadow banking entities figure prominently in EU bank exposures?

In December 2015, the EBA issued guidelines on the approach that institutions (banks and investment firms) should adopt for the purposes of setting appropriate individual and aggregate limits on exposures to shadow banking entities which carry out banking activities outside a regulated framework. In parallel to the development of the guidelines, the EBA conducted a data collection to understand better the volume and distribution of institutions’ exposures to certain types of unregulated and ‘lightly’ regulated entities and the potential impact of imposing limits on exposures to these entities.

Institutions were asked to provide information regarding their exposures to counterparties considered as ‘shadow banking entities’. ‘Exposures’ mean any asset or off-balance sheet item used in the calculation of capital requirements for credit risk under the standardised approach, without applying risk weights or degrees of risk. The exposures used in our analysis are obtained after credit risk mitigation and large exposures’ exemptions.

Our final dataset focuses on a subset of exposures that are equal to or above 0.25% of each institution’s eligible capital and it comprises 3,182 exposures with a total amount of €560 billion reported by 131 EU banks.1 As noted in EBA (2015), the banks in our sample cover approximately 56% of total assets of the EU financial sector, although the coverage is heterogeneous across countries.

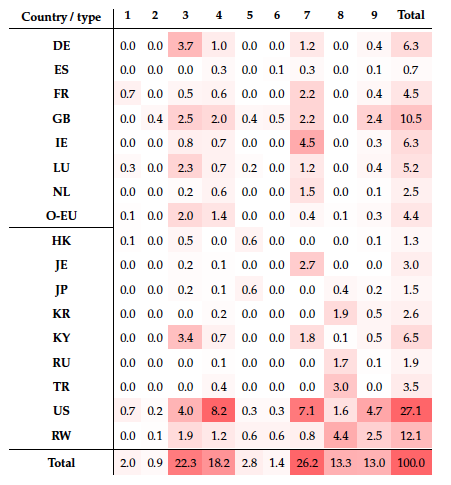

Figure 1. Distribution of EU banks exposures to shadow banking entities by country of domicile and type of shadow banking entity (weighted by size of exposure)

Figure 1 shows the different types of shadow banking entities to which EU banks are exposed. Information was collected on Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) MMFs (category 1), non-UCITS MMFs (category 2), non-MMF investment funds (category 3), finance companies (category 4), broker-dealers (category 5), credit insurers / financial guarantors (category 6), securitisations (category 7), non-equivalent banks / insurers (category 8), and a residual category labelled as ‘other’ (category 9) for entities that cannot be classified according to the types presented above.

Our data show that EU banks’ exposures are concentrated by type of shadow banking entity and also highlight the global and cross-border nature of the interconnectedness to shadow banking entities. For example, approximately 60% of EU banks’ total exposures are to entities domiciled outside the EU. In particular, these data show the strong linkages between EU banks and US-domiciled shadow banking entities, which account for approximately 27% of the total exposures in our final dataset. Regarding the top exposures by type and country of domicile of the shadow banking entities (in billions of euros), Figure 1 highlights that EU banks are most heavily exposed to finance companies domiciled in the US, followed by US securitisation vehicles, ‘other’ US shadow banking entities, securitisation vehicles domiciled in Ireland and US non-MMF investment funds. EU banks also have significant exposures to entities domiciled in the Cayman Islands, Turkey and Jersey.

Moreover, approximately 13% of EU banks’ exposures are to entities that could not be further identified, labelled as ‘other’ shadow banking entities, which highlights the information limitations for monitoring shadow banking activities. In addition, our data illustrate that the reporting banks possess limited information regarding the supervisory treatment of their shadow banking counterparties. For example, almost 90% of the exposures are to shadow banking counterparties reported as either not supervised or not further identified by the reporting bank.

We go on to show that the relationship between the banks’ geographic diversification of exposures to shadow banking entities and their own geographic complexity is positive, and it is also correlated with the banks’ size. We then analyse to what extent EU banks’ exposures to shadow banking entities are concentrated and overlapped. By “overlap”, we mean the common exposures of EU banks towards shadow banking entities, and we introduce a specific measure for this.

The increased diversification of exposures may increase overlap and therefore reduce the benefit of diversification owing to the commonalities of the sources of shocks. This is a key issue in assessing systemic risk. EU banks have low levels of individual concentration towards shadow banking entities. This diversification leads, however, to high overlap where different banks are commonly exposed to the same types of shadow banking entity. This high but shared diversification across types of shadow banking entities may potentially lead to common sources of vulnerability.

Conclusions

Overall, our analysis contributes to the understanding of the linkages between EU banks and shadow banking entities. The Global Crisis highlighted how such linkages can act as contagion paths and can lead to the amplification of shocks across borders and sectors. Therefore, for the purposes of systemic risk monitoring, our findings further reinforce the need for coordinated responses, which can be facilitated through greater cooperation and information sharing amongst regulators. Understanding the cross-sector and cross-border linkages will also equip policymakers and regulators with the necessary surveillance tools and can form a key input in the design of macroprudential policies.

Future work should investigate the liability side of banks’ balance sheets and specifically the role of shadow banking entities as a source of funding for banks. Moreover, understanding the linkages of shadow banking entities to other non-bank financial institutions is also an important part of the financial ecosystem which should be monitored. A mapping of these linkages and potential contagion paths between sectors and jurisdictions will provide a more complete picture of the interconnectedness of the banking and shadow banking system.

Authors' note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and should not be interpreted to reflect those of the ESRB, EBA or their member institutions.

References

Abad, J, M D’Errico, N Killeen, V Luz, T Peltonen, R Portes and T Urbano (2017), “Mapping the interconnectedness between EU banks and shadow banking entities,” European Systemic Risk Board Working Paper No. 40.

Acharya, V, P Schnabel and G Suarez (2013), “Securitization without risk transfer”, Journal of Financial Economics 107(3): 515-536.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2015), “Consultative Document: Identification and measurement of step-in risk”, Bank for International Settlements, December.

Covitz, D, N Liang and G Suarez (2013), “The evolution of a financial crisis: Collapse of the asset-backed commercial paper market”, Journal of Finance 68(3): 815-848.

European Banking Authority (2015), “Report on institutions’ exposures to shadow banking entities – 2015 data collection”, December.

European Systemic Risk Board (2016), “EU Shadow Banking Monitor”, No. 1, July.

Fischer, S (2015), “Financial Stability and Shadow Banks: What We Don’t Know Could Hurt Us”, speech at the “Financial Stability: Policy Analysis and Data Needs” 2015 Financial Stability Conference sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and the Office of Financial Research, Washington, D.C.

Grillet-Aubert, L, J-B Haquin, C Jackson, N Killeen and C Weistroffer (2016), “Assessing shadow banking – non-bank financial intermediation in Europe”, European Systemic Risk Board Occasional Paper, No. 10.

Endnotes

[1] The final dataset we employ excludes exposures reported by investment firms and individual exposures greater than 25% of banks’ eligible capital.