The opioid epidemic has garnered an immense amount of attention from the media and policymakers. It is typically characterised by one or more of the following facts: a three-fold rise of opioid prescriptions since 1999; a four-fold rise in prescription opioid-related mortality since 1999; and a ten-fold rise in non-prescription opioid (e.g. heroin and fentanyl) deaths since 1999 (Manchikanti et al. 2017, Hedegaard et al. 2017).

These figures suggest that prescription opioids are quite dangerous, but another calculation makes the case even clearer. According to data provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for 2016, 34% of adults used a prescription opioid (including misuse) and 0.005% of adults died of a prescription opioid overdose. These figures suggest that 1.4 out of every 100 adults who used a prescription opioid is at risk of dying, which constitutes a huge risk. However, the risk of prescription opioid death depends on the number, duration, and dose of prescriptions, not just the number of persons with a prescription. The implication is not surprising: heavy users of prescription opioids are at greatest risk of dying, particularly those who misuse opioids and have a substance use problem (Bohnert et al. 2011).

But there are relatively few such people. Less than one-third of opioid prescriptions are for 30 days or more, which is the prescription length that increases addiction probability. Only about 10% of opioid prescriptions are for the high-dosage (90 morphine milligram equivalents) amounts (CDC 2018, Scheiber et al. 2019) that are also the deadliest (Bohnert et al. 2011). Moreover, according to the CDC, in 2016, fewer than 5% of adults reported misuse of a prescription opioid and fewer than 1% reported a prescription opioid use disorder (abuse). So, it is likely that fewer than 15% of adults who had an opioid prescription were abusing opioids. Thus, the 1.4 per 100 risk of dying associated with prescription opioid use (noted above) is likely comprised of a much higher risk for a small group of heavy users/abusers and a much lower risk for a large group of typical users.

While the risk of death from opioid prescriptions is quite high, the vast majority (perhaps 85%) of prescription opioid use is not misuse (abuse), but medically prescribed. The risk of death remains low for most prescription opioid users who have relatively low-dose prescriptions for less than 30 days. This fact has not been widely recognized in research on the effects of prescription opioids, which tends to focus on the small set of abusers.

With the bimodal view of prescription opioid users in mind, consider the effect of state policies to curtail prescription opioid use, as we do in this study. A policy-induced decrease in prescription opioids is liable to adversely affect the health of those whose opioid use is medically prescribed and of the type unlikely to lead to addiction and overdose death, which is the large majority of prescription opioid users. These patients will have less access to pain relief. Left untreated, pain can lead to anxiety, depression, functional limitations, and increased health care costs (Fishbain et al. 1986, American Geriatric Association 2002, Bair et al. 2003, Chou et al. 2011). In turn, poor health can have effects on socioeconomic standing, such as labour market outcomes. Now consider a person whose use of prescription opioids is for consumption (non-medical) purposes – to get high. For this person, a policy-induced decrease in prescription opioids may improve health. However, the availability of close substitutes for non-medical use of prescription opioids, such as heroin, may also result in prescription opioid abusers simply switching substances when the punch bowl is taken away. And because substances like heroin have arguably even more serious adverse health effects, health outcomes may worsen, resulting in higher rates of mortality among users who switch substances.

Our study addresses the two sides of prescription opioid use just described by conducting analyses stratified by age and gender. It turns out that the rates of non-medical use – as well as the ratio of non-medical to medical use of prescription opioids – differ significantly by age, gender, and to a lesser extent, education. For example, approximately 16% of females aged 50 to 64 had a prescription for opioids in 2002-2006 (the early part of our period of analysis). But only 2% reported non-medical use, and about 1% reported heroin use in the past year. Purposeful misuse of prescription opioids, or use of illegal opioids, is rare among this demographic group. By contrast, among men aged 26 to 34, only 9% had a medical prescription for opioids in 2002-2006, but 9% also reported non-medical use, and 3% reported heroin use in the past year. This group has a relatively high rate of illegal drug use, and much of their prescription opioid use is misuse (Kaestner and Ziedan, 2019).

These differences in medical and non-medical use (misuse) of opioids suggest that changes in prescription opioid use resulting from state efforts had different effects on the socioeconomic outcomes of these demographic groups.

How states responded to the opioid epidemic

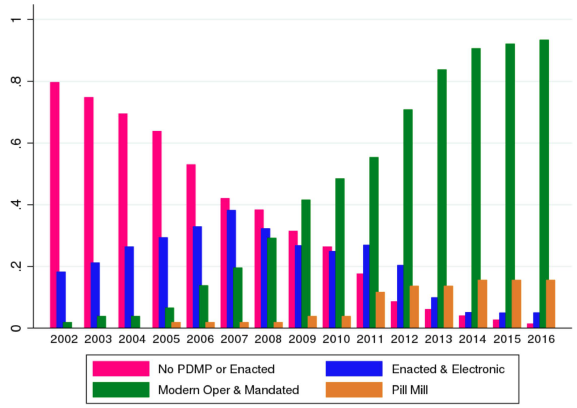

Many states have responded to the opioid epidemic by enacting a variety of laws and policies related to controlling and monitoring opioid prescribing behaviour. The most prominent state response has been the enactment, refinement, and strengthening of prescription drug monitoring programmes (PDMPs), which are widely seen as one of the most effective policies to deter opioid abuse. Between 2000 and 2010, 25 state PDMPs were established. In addition, newly established PDMPs and upgrades to existing PDMPs differ from earlier examples in that they are fully electronic, more accessible to physicians, pharmacists and other pertinent parties, and often include requirements for mandatory use. Using a classification of PDMPs that we have adopted, Figure 1 shows the variation over time within states in both the extensive margin (reflected in the creation of electronic PDMPs) and at the intensive margin (reflected in significant changes in the structure of PDMPs as shown by the growth of what we refer to as ‘modern’ PDMPs).

Figure 1

How we conducted the study

We used the variation in state prescription opioid policies shown in Figure 1 to conduct a pre- and post-test with comparison group analysis, which is sometimes referred to as difference-in-differences (DiD). The DiD approach compares changes in outcomes in a state; for example, employment pre- and post-adoption of a state law to curtail prescription opioid use compared to analogous changes in employment in states that did not adopt a law. Data for the analysis came from publicly available sources, such as the Drug Enforcement Agency (opioid sales), American Community Survey (e.g. employment) and CDC vital statistics (deaths). The years of analysis were from 2002 to 2016.

Reductions in opioids sales, particularly in urban areas

Using the approach above, we found that the adoption of these PDMPs (particularly PDMPs that have been characterised as ‘modern’) and the adoption of ‘pill mill’ legislation reduced prescription opioid sales by between 5% to 20% depending on three factors: the policy, whether it was an urban or rural area, and the type of opioid. We found the highest reduction in urban counties, where the presence of a modern PDMP was associated with approximately a 5% decrease in all opioid sales and a 9% decrease in sales of oxycodone and hydrocodone (the two most common prescription opioids in the US), although these estimates are not always significant. Pill mill laws were associated with a 17% decrease in all opioid sales and an 18% decrease in sales of oxycodone and hydrocodone.

Opioid policies and socioeconomic outcomes

We used this change in prescription opioid sales – and presumably, in opioid use – caused by the implementation of these policies to assess the effects of state policies on socioeconomic outcomes. The outcomes we analysed are employment, weeks worked per year, personal earnings, receipt of social welfare cash benefits, marital status, and a measure of disability. The information on these socioeconomic variables was obtained from individual-level data from the American Community Surveys (ACS), which annually survey 1% of the US population.

As noted, we conducted analyses stratified by age and gender because of the differences in medical and non-medical use of prescription opioids across these groups. We found no economically or statistically meaningful effect of policy-induced reductions in opioid sales on employment, marriage, income, or disability across these cohorts. In short, we found no evidence that curtailing prescription opioid use through PDMPs and pill mill laws had adverse or beneficial consequences on wellbeing.

Opioid policies and mortality

Our analysis of the effect of state policies on mortality also indicated that these policies had little effect despite reducing prescription opioid sales by between 5% and 20%. Our findings that PDMPs and pill mill laws have small to no significant effect on mortality are consistent with prior studies, although the literature remains relatively sparse.

Conclusion

There are serious risks associated with prescription opioid use, but there are also important benefits. To assess the costs and benefits of prescription opioid use, consider the peak year of opioid prescribing. In 2012, 255 million opioid prescriptions were dispensed, and approximately 14,240 overdose deaths occurred from prescription opioids. These figures indicate that every 17,907 opioid prescriptions are associated with one additional death, which sounds like a trivial risk (it is twice the lifetime risk of dying from a cataclysmic storm). But even a small risk is significant because of the value of every life. If we assume that the value of a statistical life is $9.1 million (EPA 2018), then each of the 17,907 opioid prescriptions that are associated with an additional death should be worth $580 to make them worthwhile. In other words, if a consumer would be willing to pay $580 for a prescription opioid, then that opioid prescription is worth the risk of dying associated with it. Does a typical opioid prescription (16-day supply) generate $580 in benefits? As far as we know, there is no evidence to answer this question.

And yet, the value of opioid prescription use, and whether prescription opioid use should be reduced, depends on the answer to precisely that question. If the reduction in pain and consequent salutary effects of prescription opioid use are worth more than $580, then the risk of death associated with a prescription may be worth it, and efforts to curtail use would decrease welfare. The growing concern that the pendulum has swung too far and that appropriate (beneficial) prescription opioid use is being curtailed may be justified (Dowell et al. 2019, Bohnert et al. 2019, Krebs et al. 2018).

In our study, we found that state policies reduced prescription opioids by between 5% and 20%, but had no statistically significant effects on mortality or socioeconomic outcomes. There are a couple of implications of our findings, all of which require further study.

- First, we found no decreases in wellbeing. This suggests that the reductions in prescription opioid use we observed were of relatively low value and not particularly health improving for the majority of prescription opioid users who had relatively low-dose, short-term prescriptions. Alternatively, it may be that there was no reduction in these types of prescriptions, and therefore no change in outcomes for the majority of prescription opioid users.

- Second, we found no increases in wellbeing; for instance, a decrease in mortality. This suggests that the reductions in prescription opioid use we observed were not concentrated among heavy users/abusers of prescription opioids. Alternatively, it may be that prescriptions for these users were reduced, but that most of them switched to substitutes such as heroin and fentanyl.

- Finally, both types of consequences may have occurred but offset one another, meaning that on average we found no effects. It would be valuable to stratify the analyses by segregating typical users of prescription opioids from abusers and assessing the effects of state polices on each group.

References

AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons (2002), “The management of persistent pain in older persons”, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 50(6 Suppl): S205.

Bair, M J, R L Robinson, W Katon, and K Kroenke (2003), “Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review”, Archives of Internal Medicine 163(20): 2433-2445.

Bohnert, A S, M Valenstein, M J Bair, D Ganoczy, J F McCarthy, M A Ilgen, and F C Blow (2011), “Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths”, Jama 305(13): 1315-1321.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016)," CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States (2016)", Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65(1): 1-49.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018), 2018 Annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes—United States.

Dowell, D, T Haegerich, and R Chou (2019), “No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing”, New England Journal of Medicine 380(24): 2285-2287.

Fishbain, D A, M Goldberg, B R Meagher, R Steele, and H Rosomoff (1986), “Male and female chronic pain patients categorized by DSM-III psychiatric diagnostic criteria”, Pain 26(2): 181-197.

Hedegaard, H, M Warner and A M Miniño (2007), “Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016”, NCHS Data Brief No. 294.

Kaestner, R and E Ziedan (2019), “Mortality and Socioeconomic Consequences of Prescription Opioids: Evidence from State Policies”, NBER Working Paper No. 26135.

Krebs, E et al. (2018), “Effect of opioid vs non-opioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE randomized clinical trial”, Jama 319(9), 872-882.

Manchikanti, L et al. (2017), “Responsible, Safe, and Effective Prescription of Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) Guidelines”, Pain Physician 20: S3-S92. https://www.painphysicianjournal.com/current/pdf?article=NDIwMg%3D%3D&jo...

Schieber, L Z, G P Guy, P Seth, R Young, C L Mattson, C A Mikosz, and R A Schieber (2019), “Trends and Patterns of Geographic Variation in Opioid Prescribing Practices by State, United States, 2006-2017”, JAMA network open 2(3): e190665-e190665.

Von Korff, M, A Kolodny, R A Deyo, and R Chou (2011), “Long-term opioid therapy reconsidered”, Annals of internal medicine 155(5sche): 325-328.

Endnotes

[1] If the policy-induced decrease in prescription opioids affects primarily opioid use that had relatively low-health benefits (because of inappropriate prescribing and the moral hazards associated with health insurance, for instance), then the adverse health consequences of the policy-induced decrease in opioids may be lessened. The use of therapeutic substitutes may also lessen the consequences of decreased access to prescription opioids.

[2] Data on prescription opioids dispensed per year were obtained from the CDC at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html. Data on prescription opioid overdoses per year were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse at https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.