The introduction of the oral contraceptive pill in 1960 represents one of the most remarkable medical advances of the 20th century. A large body of research documents that increasing legal or financial access to modern contraceptives improved women’s educational and labour market outcomes (Bailey and Lindo 2018, Goldin and Katz 2002). While the pill is to this date the most popular form of prescribed contraceptive among adolescents, hormone-based contraceptives have grown increasingly controversial over the last decade due to concerns about adverse side effects on mental health (Anderl et al. 2020, Skovlund, Mørch, Kessing, and Lidegaard 2016, Skovlund, Mørch, Kessing, Lange, and Lidegaard 2018, Zethraeus et al. 2017). In our paper (Costa-Ramón et al. 2023), we use Danish population-level administrative data and implement two complementary empirical strategies to comprehensively analyse the consequences of combined oral contraceptive pill use on teenage girls’ mental health.

Event study design: Pill initiation and mental health

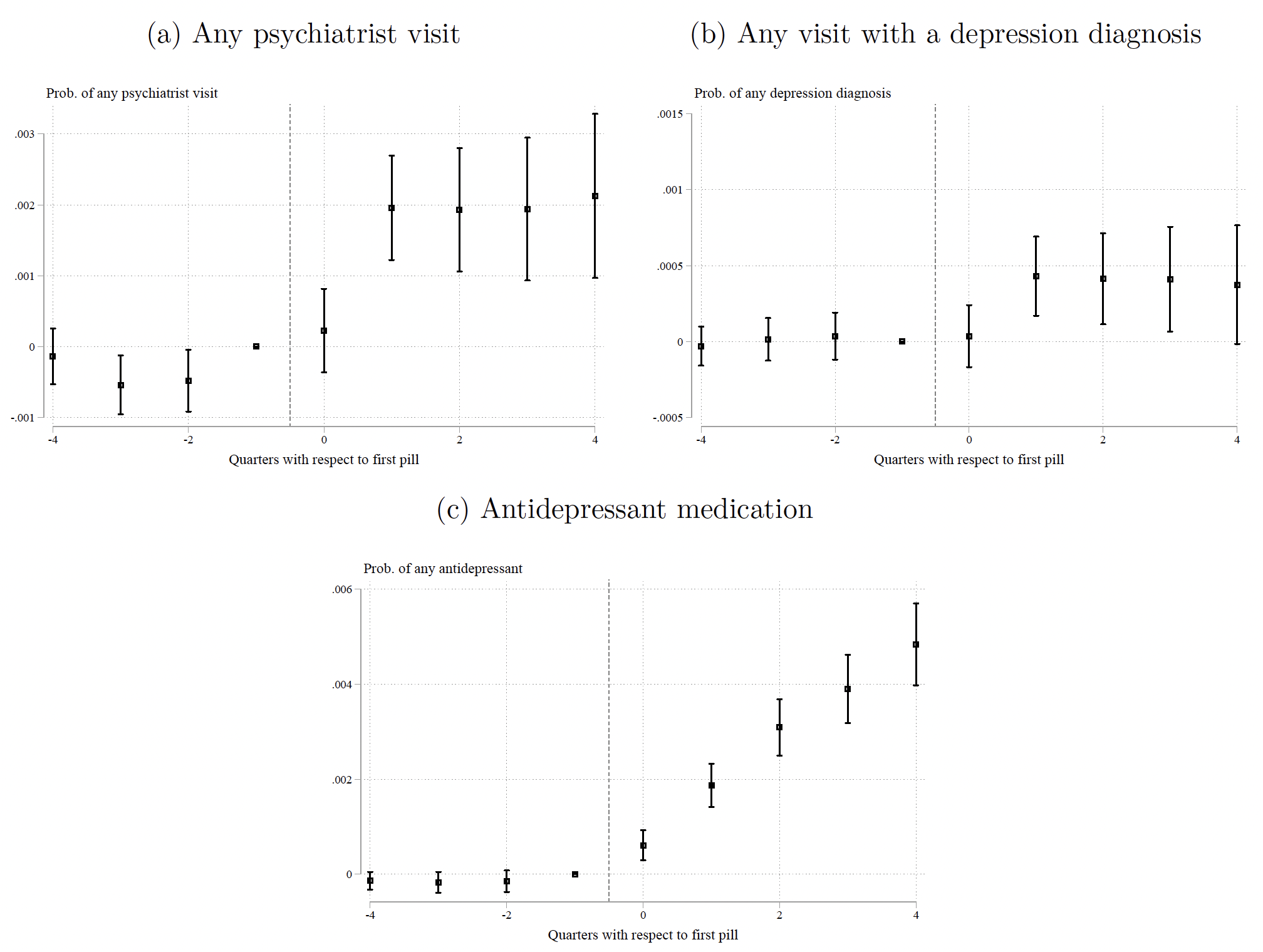

We begin by exploiting the variation in the timing of pill initiation in an event study framework and focus on a balanced panel of girls who start using the combined oral contraceptive pill between the ages of 12 and 17. The observations date from five quarters before and four quarters after the pill initiation.

We find that mental health outcomes deteriorate shortly after pill initiation (Figure 1). One quarter after the first pill prescription, the probability of a psychiatric visit and a depression diagnosis increases by 17% and 40%, respectively. In addition, one year after the first combined oral contraceptive prescription, the probability of antidepressant use is 65% higher. Although the prevalence of these outcomes is low (only 0.8% have an antidepressant prescription the quarter prior to pill initiation), the relative increases are large, and it is worth highlighting that we are potentially (only) capturing the most severe cases requiring diagnosis or medication.

Figure 1 Oral contraceptive initiation and mental health outcomes

What do these results imply about the role of oral contraceptives in the increased use of antidepressants among adolescent girls? To answer this question, we perform a back-of-the-envelope calculation and find that approximately 15% of the upsurge in antidepressant use among adolescent girls born between 1986 and 1994 can be attributed to increased oral contraceptive use.

The findings are highly compelling as there is no evidence of pre-trends for any of the outcomes we analyse. The richness of the register data allows us to further shed light on the plausibility of the key identification assumptions. For example, our results are robust to excluding girls who are at risk of having mental health problems around the time of pill initiation for independent concurrent reasons (e.g. girls with an unwanted pregnancy). Similarly, we find no evidence of increased risky behaviours (e.g. hospital visits due to alcohol abuse or intoxication, screening for sexually transmitted diseases, or chlamydia diagnosis) around the time of oral contraceptive initiation.

We also rely on insights from the medical literature documenting weaker associations between mental health outcomes and progestin-only contraceptives (compared to combined pills) and show that girls who use progestin-only products do not experience deterioration in their mental health around the time of first pill use. Finally, we find that teenage girls whose first pill prescription have a different hormonal composition have similar trajectories in their GP visits. This suggests that our main findings are unlikely to be due to increased interactions between patients and physicians (e.g. to refill prescriptions).

The role of the primary care provider

We next quantify the impact of the type of primary care provider (GP), defined as their propensity to prescribe oral contraceptives to adolescents, on mental health outcomes. In order to address concerns of endogenous patient-provider matches, we assign children to the provider treating them at age 12. This provider is chosen by the child’s parents from the pool of available providers in their catchment area. We define a GP’s prescribing tendency as their rate of prescribing leave-one-out combined oral contraceptives among the other 12- to 18-year-olds that were seen in that clinic in that year.

There is substantial variation in GP prescribing tendency: providers at the 90th percentile of the distribution have a prescribing rate that is 16.6 percentage points higher than the providers at the 10th percentile. The difference in an interquartile shift is 8 percentage points. These differences are large when compared to the mean prescribing rate of 20%. Importantly, the variation in GP prescribing tendency is orthogonal to a rich set of observable child and parental characteristics as well as to girls’ outcomes measured at age 12. As such, provider assignment is unlikely to be related to unobserved determinants of girls’ contraceptive use and mental health outcomes.

Turning to the role of the GP practice style on oral contraceptive use, we find that switching from a provider at the 10th percentile of the distribution to one at the 90th percentile increases the likelihood of contraceptive use by age 15 by 6.5% and by age 16 by 4%. We also find that the GP prescribing tendency impacts girls’ mental health outcomes: assignment to a GP with a one-standard-deviation-higher pill-prescribing tendency increases the likelihood of having a psychiatric contact between ages 16 to 18 by 2.2%, the likelihood of a depression diagnosis by 5.2%, and the probability of using antidepressants by 4%.

What is the mechanism driving the impact of the GP practice style on the mental health outcomes of adolescent girls? Primary care providers with different oral-contraceptive prescribing tendencies may affect patient outcomes by not only changing patients’ likelihood of using oral contraceptives, but also through other dimensions of care that are correlated with their prescribing tendency. In order to probe potential mechanisms, we first examine the relationship between GPs’ tendency to prescribe oral contraceptives and the mental health outcomes of adolescent boys and find no impact on their mental health. We next examine the relationship between GP prescribing tendency and hospitalisations for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions, a proxy for quality of care. We again find no evidence that physicians with different pill-prescribing tendencies have different quality of care. We cautiously interpret these findings as indicating that in our context, contraceptive use is likely the main channel.

Filling an important gap in the existing literature

An extensive body of work examines the consequences of the introduction of the pill, focusing on the effects of access to the pill on women’s fertility, marriage, and career trajectories (Bailey 2006, Bailey et al. 2012, Goldin and Katz 2002). The study by Valder (2022) finds a link between pill access at ages 14 to 21 and worse mental health outcomes at age 60. Our work adds to this literature by providing novel evidence of the direct effect of the contraceptive pill on mental health.

We also add to studies linking provider practice styles and patient outcomes. This literature has documented consequences of variation in physician prescribing tendency in ADHD medications (Dalsgaard et al. 2014), opioids (Eichmeyer and Zhang, 2022 2023), and antidepressants (Bhalotra et al. 2023, Cuddy and Currie 2020, Currie and Zwiers 2023). We document the variation in providers’ tendency to prescribe the contraceptive pill and analyse its impact on patient outcomes.

Finally, our project contributes to the rapidly growing economic literature on the determinants of mental health disorders. The majority of this research documents the effects of in-utero conditions on mental health during adulthood (e.g. Adhvaryu et al. 2019, Almond and Mazumder 2011, Chorniy et al. 2020), with emerging evidence indicating the onset of these conditions during early childhood (Persson and Rossin-Slater 2018). Studies investigating the postnatal environment focus on the effects of economic resources (e.g. Baird et al. 2013, Golberstein et al. 2019, Ridley et al. 2020, Schaller and Zerpa 2019), educational environment (e.g. Dee and Sievertsen 2018, Jakobsson et al. 2013, Marcus et al. 2020, Rossin-Slater et al. 2020), or social media (Arenas-Arroyo et al. 2023, Levy et al. 2022). Our study adds to this literature by examining the effects of a widely prescribed medication on the mental health outcomes of adolescent girls.

Adolescent mental health crisis and the road ahead

Concerns about adolescent mental health has reached new heights in recent years and led some to declare that the US is now in a mental health crisis (American Academy of Pediatrics 2021). Child mental health is likely to remain a global priority in the coming years. As such, understanding the causal drivers of childhood mental health disorders is of paramount interest.

Overall, our study highlights the importance of carefully weighing the individual benefits against the potential costs of using the pill among adolescent girls. Our finding that primary care providers exert a significant influence on their patients’ oral contraceptive use suggests that one way to address the detrimental consequences of the pill on adolescent mental health could be through supply-side education policies.

References

Adhvaryu, A, J Fenske, and A Nyshadham (2019), “Early life circumstance and adult mental health”, Journal of Political Economy 127(4): 1516–49.

Almond, D, and B Mazumder (2011), “Health capital and the prenatal environment: The effect of Ramadan observance during pregnancy”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3(4): 56–85.

American Academy of Pediatrics (2021), “AAP-AACAP-CHA declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health”.

Anderl, C, G Li, and F S Chen (2020), “Oral contraceptive use in adolescence predicts lasting vulnerability to depression in adulthood”, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 61(2): 148–56.

Arenas-Arroyo, E, D Fernandez-Kranz, and N Nollenberger (2023), “Online media and the adolescent mental health crisis”, VoxEU.org, 9 April.

Bailey, M J (2006), “More power to the pill: The impact of contraceptive freedom on women’s life cycle labor supply”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 121(1): 289–320.

Bailey, M J, B Hershbein, and A R Miller (2012), “The opt-in revolution? Contraception and the gender gap in wages”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(3): 225–54.

Bailey, M J, and J M Lindo (2018), “Access and use of contraception and its effects on women’s outcomes in the US”, in S L Averett, L M Argys, and S D Hoffman (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy, Oxford Handbooks.

Baird, S, J de Hoop, and B Ózler (2013), “Income shocks and adolescent mental health”, Journal of Human Resources 48(2): 370–403.

Bhalotra, S, N M Daysal, and M Trandafir (2023), “Antidepressant use and school performance: Evidence from Danish administrative data”, working paper.

Chorniy, A, J Currie, and L Sonchak (2020), “Does prenatal WIC participation improve child outcomes?”, American Journal of Health Economics 6(2): 169–98.

Costa-Ramón, A, N M Daysal, and A Rodríguez-González (2023), “The oral contraceptive pill and adolescents’ mental health”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18269.

Cuddy, E, and J Currie (2020), “Treatment of mental illness in American adolescents varies widely within and across areas”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the US of America 117(39): 24039–46.

Currie, J, and E Zwiers (2023), “Medication of postpartum depression and maternal outcomes”, Journal of Human Resources, 1021-11986R1.

Dalsgaard, S, H S Nielsen, and M Simonsen (2014), “Consequences of ADHD medication use for children’s outcomes”, Journal of Health Economics 37(1): 137–51.

Dee, T S, and H H Sievertsen (2018), “The gift of time? School starting age and mental health”, Health Economics (27): 781–802.

Eichmeyer, S, and J Zhang (2022), “Pathways into opioid dependence: Evidence from practice variation in emergency departments”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 14(4): 271–300.

Eichmeyer, S, and J Zhang (2023), “Primary care providers’ influence on opioid use and its adverse consequences”, Journal of Public Economics (217): 104784.

Golberstein, E, G Gonzales, and E Meara (2019), “How do economic downturns affect the mental health of children? Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey”, Health Economics 28(8): 955–70.

Goldin, C, and L F Katz (2002), “The power of the pill: Oral contraceptives and women’s career and marriage decisions”, Journal of Political Economy 110(4): 730–70.

Jakobsson, N, M Persson, and M Svensson (2013), “Class-size effects on adolescents’ mental health and well-being in Swedish schools”, Education Economics 21(3): 248–63.

Levy, R, A Makarin, and L Braghieri (2022), “Social media and mental health”, VoxEU.org, July 22.

Marcus, J, S Reif, A Wuppermann, and A Rouche (2020), “Increased instruction time and stress-related health problems among school children”, Journal of Health Economics 70.

Persson, P, and M Rossin-Slater (2018), “Family ruptures, stress, and the mental health of the next generation”, American Economic Review 108(4–5): 1214–52.

Ridley, M, G Rao, F Schilbach, and V Patel (2020), “Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms”, Science 370(6522).

Rossin-Slater, M, M Schnell, H Schwandt, S Trejo, and L Uniat (2020), “Local exposure to school shootings and youth antidepressant use”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the US of America 117(38): 23484–9.

Schaller, J, and M Zerpa (2019), “Short-run effects of parental job loss on child health”, American Journal of Health Economics 5(1): 8–41.

Skovlund, C W, L S Mørch, L V Kessing, T Lange, and J Lidegaard (2018), “Association of hormonal contraception with suicide attempts and suicides”, American Journal of Psychiatry 175(4): 336–42.

Skovlund, C W, L S Mørch, L V Kessing, and O Lidegaard (2016), “Association of hormonal contraception with depression”, JAMA Psychiatry 73(11): 1154–62.

Valder, F (2022), “Two sides of the same pill? Fertility control and mental health effects of the contraceptive pill”, CEBI Working Paper 03/2022, 03/22.

Zethraeus, N, A Dreber, E Ranehill, L Blomberg, F Labrie, B von Schoultz, M Johannesson, and A L Hirschberg (2017), “A first-choice combined oral contraceptive influences general well-being in healthy women: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial”, Fertility and Sterility 107(5): 1238–45.